Lake Timsah

Lake Timsah, also known as Crocodile Lake (Arabic: بُحَيْرة التِّمْسَاح); is a lake in Egypt on the Nile delta. It lies in a basin developed along a fault extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez through the Bitter Lakes region.[1] In 1800, a flood filled the Wadi Tumilat, which caused Timsah's banks to overflow and moved water south into the Bitter Lakes about nine miles (14 km) away.[2] In 1862, the lake was filled with waters from the Red Sea, and became part of the Suez Canal.[3]

| Lake Timsah | |

|---|---|

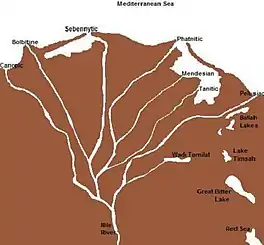

Map of the Nile Delta showing Lake Timsah at center right. | |

Lake Timsah | |

| Location | Al Isma'iliyah, Egypt |

| Coordinates | 30.56667°N 32.28333°E |

| Lake type | Hydrographic |

| Surface area | 14 km2 (5.4 sq mi) |

| Water volume | 80,000,000 m3 (2.8×109 cu ft) |

Geography

Lake Timsah lies within a depression that spans the isthmus between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea.[4] The lowest points of the depression form shallow natural lakes, of which Timsah is one.[4] The surface area of Lake Timsah covers 5.4 square miles.[5] Most of the lake is marshy and depth rarely exceeds 3 feet (1 metre).[6]

It has been asserted that, in ancient times, Lake Timsah was the northern terminus of the Red Sea.[7]

On March 4, 1863, the city of Ismailia, named in honor of the viceroy Ismail Pasha, arose on Lake Timsah's northern bank.[9] Several beaches overlook the lake, including the Moslem Youth, Fayrouz, Melaha, Bahary, Taawen, and a few Suez Canal Authority beaches.[5]

Canals

Canal of the Pharaohs

Lake Timsah possibly first became a juncture for canal construction approximately 4,000 years ago during the Middle Kingdom of Egypt,[10] and was expanded by Darius I.[11]

Suez Canal

Suez Canal construction in the vicinity of Lake Timsah began in 1861 on the segment north of the lake.[12] Initial preparations included the construction of sheds to house 10,000 workers, steam sawmills, and importation of large quantities of wheelbarrows and wooden planks.[12] 3,000 laborers dug a channel (Ismailia Canal) from the Nile to Lake Timsah in 1861 and 1862, which brought a fresh water supply to the area.[12][13] It was also proposed to construct a halfway port at this point along the canal.[14] The Ismailia section of the Suez Canal, which connected Lake Manzala to Lake Timsah, was completed in November 1862.[13] Construction of the segment was completed with forced labor, which expanded the workforce to 18,000 men.[12][13] The trench measured 50 feet (15 m) wide by four to six feet deep and connected Lake Timsah to the Mediterranean Sea.[12] Work began south of Lake Timsah in 1862-1863 as expansion continued on the northern segment.[12] Forced labor was used during canal construction from March 1862 until Ismail Pasha outlawed the practice in 1864.[13] As a result of the canal, waters from Lake Manzaleh flowed into Lake Timsah.[13] Expansion continued on the northern segment until 1867 and on the southern segment until 1876.[12]

Environment

Salinity

Lake Timsah is a brackish lake that experiences significant variations in salinity.[6] Human engineering projects have impacted salinity, with resulting changes in the lake's biota.[6] Decreases in salinity were noted as early as 1871 following Suez Canal construction, and subsequent enlargement of the channel from the Nile and other construction projects increased the inflow of fresh water to the lake.[6] The El-Gamil outlet serves as Lake Timsah's principal source of salt water.[6] Timsah's main source of fresh water was annual Nile flooding until the Aswan High Dam interrupted these flows in 1966, although groundwater also accounts for much of the lake's freshwater supply.[6] Lake Timsah experiences both stratification variations in salinity and seasonal surface variations in salinity, and in recent decades freshwater taxa have been overtaking brackish taxa.[6]

Pollution

In 2002, a study was conducted to check the concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in fish and shellfish species that locals consume from the lake.[15] Samples included tilapia, crabs, bivalves, clams and gastropods.[15] The results showed that crabs contained "significantly higher concentrations of both total and carcinogenic PAHs than other species, while clams contained significantly lower levels of PAHs."[15]

In 2003, a number of groups attempted to relieve the lake of pollution.[16] It was a significant event for the local community, since the lake is of economic importance to the city and its fishermen.[16]

Notes

- Gmirkin, Russell E. (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 231. ISBN 0-567-02592-6.

- Hoffmeier, p.43

- Stanley, p.32

- Jerry R. Rogers, Glenn Owen (2004). Water Resources and Environmental History. ASCE Publications. p. 124. ISBN 9780784475508. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- "Ismailia". Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- Stephan Gollasch, Andrew N. Cohen (2006). Bridging Divides: Maritime Canals as Invasion Corridors. Springer. p. 229. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, s.v. "Suez Canal". Accessed 14 May 2008.

- Nourse, p.54

- Shea, William H. "A Date for the Recently Discovered Eastern Canal of Egypt" Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 226 (Apr., 1977), pp. 31-38

- Paice, Patricia "Persians" in Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, eds. Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt(New York: Routledge, 1999),

- Royal Statistical Society (Great Britain), Statistical Society (Great Britain). (1887). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Royal Statistical Society. pp. 503–509. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- W.O. Henderson (2006). The Industrial Revolution on the Continent: Germany, France, Russia 1800-1914. W.O. Henderson. p. 151. ISBN 9780415382021. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- Rogers, Jerry R.; Brown, Glenn Owen; Garbrecht, Jürgen (2004). Water Resources and Environmental History. ASCE Publications. p. 124. ISBN 0-7844-0738-X.

- "US EPA". Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- Yasmine El-Rashidi. "Making a city livable". Al-Ahram News. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

References

- Hoffmeier, James Karl (2005). Ancient Israel in Sinai. Oxford University Press US. ISBN 0-19-515546-7.

- Stanley, Henry Morton. My Early Travels and Adventures in America and Asia.

- Nourse, Joseph Everett. The Maritime Canal of Suez.