Ancient Egyptian creation myths

Ancient Egyptian creation myths are the ancient Egyptian accounts of the creation of the world. The Pyramid Texts, tomb wall decorations, and writings, dating back to the Old Kingdom (c. 2700–2200 BCE) have provided the majority of information regarding ancient Egyptian creation myths.[1] These myths also form the earliest religious compilations in the world.[2] The ancient Egyptians had many creator gods and associated legends. Thus, the world or more specifically Egypt was created in diverse ways according to different parts of ancient Egypt.[3] Some versions of the myth indicate spitting, others masturbation, as the act of creation. The earliest god, Ra and/or Atum (both being creator/sun gods), emerged from a chaotic state of the world and gave rise to Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), from whose union came Geb (earth) and Nut (sky), who in turn created Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys. An extension to this basic framework was the Osiris myth involving Osiris, his consort Isis, and their son Horus. The murder of Osiris by Set, and the resulting struggle for power, won by Horus, provided a powerful narrative linking the ancient Egyptian ideology of kingship with the creation of the cosmos.

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

In all of these myths, the world was said to have emerged from an infinite, lifeless sea when the sun rose for the first time, in a distant period known as zp tpj (sometimes transcribed as Zep Tepi), "the first occasion".[4] Different myths attributed the creation to different gods: the set of eight primordial deities called the Ogdoad, the contemplative deity Ptah, and the mysterious, transcendent god Amun. While these differing cosmogonies competed to some extent, in other ways they were complementary, as different aspects of the Egyptian understanding of creation.

Common elements

The different myths have some elements in common. They all held that the world had arisen out of the lifeless waters of chaos, called Nu. They also included a pyramid-shaped mound, called the benben, which was the first thing to emerge from the waters. These elements were likely inspired by the flooding of the Nile River each year; the receding floodwaters left fertile soil in their wake, and the Egyptians may have equated this with the emergence of life from the primeval chaos. The imagery of the pyramidal mound derived from the highest mounds of earth emerging as the river receded.[5]

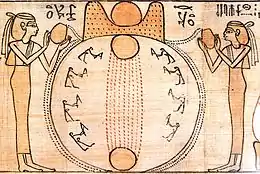

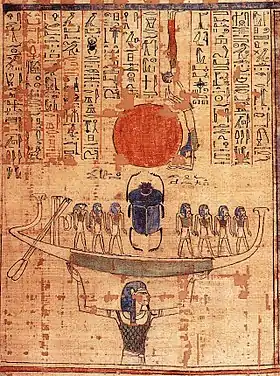

The sun was also closely associated with creation, and it was said to have first risen from the mound, as the general sun-god Ra or as the god Khepri, who represented the newly-risen sun.[6] There were many versions of the sun's emergence, and it was said to have emerged directly from the mound or from a lotus flower that grew from the mound, in the form of a heron, falcon, scarab beetle, or human child.[6][7]

Another common element of Egyptian cosmogonies is the familiar figure of the cosmic egg, a substitute for the primeval waters or the primeval mound. One variant of the cosmic egg version teaches that the sun god, as primeval power, emerged from the primeval mound, which stood in the chaos of the primeval sea.[8]

Cosmogonies

The different creation accounts were each associated with the cult of a particular god in one of the major cities of Egypt: Hermopolis, Heliopolis, Memphis, and Thebes.[9] To some degree, these myths represent competing theologies, but they also represent different aspects of the process of creation.[10]

Hermopolis

The creation myth promulgated in the city of Hermopolis focused on the nature of the universe before the creation of the world. The inherent qualities of the primeval waters were represented by a set of eight gods, called the Ogdoad. The goddess Naunet and her male counterpart Nu represented the stagnant primeval water itself; Huh and his counterpart Hauhet represented the water's infinite extent; Kek and Kauket personified the darkness present within it; and Amun and Amaunet represented its hidden and unknowable nature, in contrast to the tangible world of the living. The primeval waters were themselves part of the creation process, therefore, the deities representing them could be seen as creator gods.[10] According to the myth, the eight gods were originally divided into male and female groups.[11] They were symbolically depicted as aquatic creatures because they dwelt within the water: the males were represented as frogs, and the females were represented as snakes.[12] These two groups eventually converged, resulting in a great upheaval, which produced the pyramidal mound. From it emerged the sun, which rose into the sky to light the world.[13]

Heliopolis

In Heliopolis, the creation was attributed to Atum, a deity closely associated with Ra, who was said to have existed in the waters of Nu as an inert potential being. Atum was a self-engendered god, the source of all the elements and forces in the world, and the Heliopolitan myth described the process by which he "evolved" from a single being into this multiplicity of elements.[14][15] The process began when Atum appeared on the mound and gave rise to the air god Shu and his sister Tefnut,[16] whose existence represented the emergence of space amid the waters.[17] To explain how Atum did this, the myth uses the metaphor of masturbation, with the hand he used in this act representing the female principle inherent within him.[18] He is also said to have "sneezed" and "spat" to produce Shu and Tefnut, a metaphor that arose from puns on their names.[19] Next, Shu and Tefnut coupled to produce the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut, who defined the limits of the world.[20] Geb and Nut in turn gave rise to four children, who represented the forces of life: Osiris, god of fertility and regeneration; Isis, goddess of motherhood; Set, the god of chaos; and Nephthys, the goddess of protection. The myth thus represented the process by which life was made possible. These nine gods were grouped theologically as the Ennead, but the eight lesser gods, and all other things in the world, were ultimately seen as extensions of Atum.[21][22]

Memphis

The Memphite version of creation centered on Ptah, who was the patron god of craftsmen. As such, he represented the craftsman's ability to envision a finished product, and shape raw materials to create that product. The Memphite theology said that Ptah similarly created the world.[23] This, unlike the other Egyptian creations, was not a physical but an intellectual creation by the Word and the Mind of God.[24] The ideas developed within Ptah's heart (regarded by the Egyptians as the seat of human thought) were given form when he named them with his tongue. By speaking these names, Ptah produced the gods and all other things.[25]

The Memphite creation myth coexisted with that of Heliopolis, as Ptah's creative thought and speech were believed to have caused the formation of Atum and the Ennead.[26] Ptah was also associated with Tatjenen, the god who personified the pyramidal mound.[25]

Thebes

Theban theology claimed that Amun was not merely a member of the Ogdoad, but the hidden force behind all things. There is a conflation of all notions of creation into the personality of Amun, a synthesis which emphasizes how Amun transcends all other deities in his being "beyond the sky and deeper than the underworld".[27] One Theban myth likened Amun's act of creation to the call of a goose, which broke the stillness of the primeval waters and caused the Ogdoad and Ennead to form.[28] Amun was separate from the world, his true nature was concealed even from the other gods. At the same time, however, because he was the ultimate source of creation, all the gods, including the other creators, were merely aspects of Amun. Amun eventually became the supreme god of the Egyptian pantheon because of this belief.[29]

Amun is synonymous with the growth of Thebes as a major religious capital. But it is the columned halls, obelisks, colossal statues, wall reliefs, and hieroglyphic inscriptions of the Theban temples that we look to gain the true impression of Amun's superiority. Thebes was thought of as the location of the emergence of the primeval mound at the beginning of time.[30]

References

- Leeming, David Adams (2010). Creation Myths of the World. Santa Barbaro: ABC-CLIO. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-59884-174-9.

- Hart, George (2004). Egyptian Myths. Austin, Texas: University of Texas. p. 9. ISBN 0-292-72076-9.

- M.V., Seton-Williams (1999). Egyptian Legends and Stories. U.S.A: Barnes & Noble Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 0-7607-1187-9.

- Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. p. 466. ISBN 0-521-77483-7.

- Fleming, Fergus; Alan Lothian (1997). The Way to Eternity: Egyptian Myth. Amsterdam: Duncan Baird Publishers. pp. 24, 27, 30. ISBN 0-7054-3503-2.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 144.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 206–207. ISBN 0-500-05120-8.

- Leeming, Creation Myths of the World, p.104

- Fleming and Lothian, Way to Eternity, pp. 24-28.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 126.

- Fleming and Lothian, Way to Eternity, p. 27.

- Wilkinson, Complete Gods and Goddesses, p. 78.

- Fleming and Lothian, Way to Eternity, pp. 27-28.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 143–145.

- Wilkinson, Complete Gods and Goddesses, pp. 99-100.

- Fleming and Lothian, Way to Eternity, p. 24.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 145.

- Wilkinson, Complete Gods and Goddesses, pp. 18, 99.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 143.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 44.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, pp. 144-145.

- Wilkinson, Complete Gods and Goddesses, p. 99.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, pp.172-173.

- Seton-Williams, Egyptian Legends and Stories, p.13

- Fleming and Lothian, Way to Eternity, p. 25.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 172.

- Hart, Egyptian Myths, p.22

- Fleming and Lothian, Way to Eternity, pp. 28-29.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, pp.182-183.

- Hart, Egyptian Myths, pp.22-24