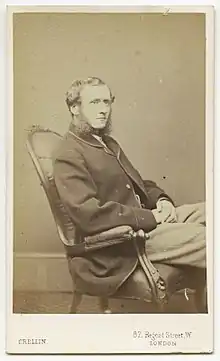

Edward Spencer Beesly

Edward Spencer Beesly (/ˈbiːzli/; 23 January 1831 – 7 March 1915) was an English positivist, trades union activist, and historian.

Edward Spencer Beesly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 January 1831 Feckenham, Worcestershire, England |

| Died | 7 March 1915 (aged 84) St Leonards, Sussex, England |

| Occupation | Historian, philosopher and positivist |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Wadham College, Oxford |

| Period | 19th century |

Life

He was born on 23 January 1831 in Feckenham, Worcestershire, the eldest son of the Rev. James Beesly and his wife, Mary Fitzgerald, of Queen's county, Ireland.[1] After reading Latin and Greek with his father, in the autumn of 1846 Beesly was sent to King William's College on the Isle of Man, an evangelical establishment whose inadequate instruction and low moral tone were later depicted in Eric, or, Little by Little, by his school friend F. W. Farrar.

In 1849 Beesly entered Wadham College, Oxford, another evangelical stronghold and the original centre of the English positivist movement.[1] He held two exhibitions and a Bible clerkship. His flair for quoting scripture yielded to radical rhetoric under the influence of his tutor Richard Congreve, a covert disciple of Auguste Comte's positivism. Along with his Wadham friends Frederic Harrison and John Henry Bridges, Beesly actively engaged in the debates of the Oxford Union and became recognised as a Comtist, though his adhesion to the French philosophy was still tenuous.

Beesly received his BA in 1854 and proceeded MA in 1857. After failing to secure a first-class (he obtained seconds in classical moderations and literae humaniores) or a fellowship, he became an assistant master at Marlborough College. His brother Augustus Henry, a historian and classical scholar, also taught at the school. Beesly left for London in 1859 to serve as principal of University Hall, a student residence in Gordon Square serving University College. The next year he was appointed professor of history there and professor of Latin at Bedford College for women, with a combined salary of £300. He also had a private income. His tall, willowy figure became a familiar sight in the Reform Club and London drawing-rooms, including that of George Eliot and George Henry Lewes, whose Fortnightly Review welcomed Beesly's articles.

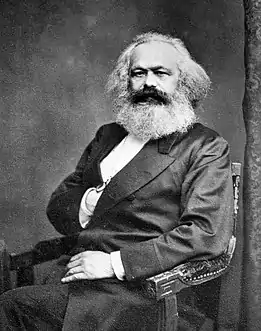

Beesly joined Congreve, Bridges, and Harrison, both now in London, in supporting the struggle of the workers in the building trades for shorter hours. He also attacked the economic theories used by critics of the "new model" trade unions of the 1860s. The notoriety he gained culminated in 1867, when he declared in the aftermath of the "Sheffield outrages" that a trade union murder was no worse than any other: he almost lost his post at University Hall and Punch dubbed him "Dr Beastly". His radical agenda included promoting international solidarity among working-class leaders. He helped organise the most important pro-Union demonstration in England during the American Civil War, and he chaired the historic meeting (28 September 1864) advocating co-operation between English and French workers in support of Polish nationalism, which led to the formation of the International Working Men's Association (the First International), soon dominated by his friend Karl Marx.

Foreign affairs were always a passion of Beesly's. For International Policy, a positivist volume published in 1866, he wrote on British sea power, asserting a connection between Protestantism and commercial immorality. A critic of imperialism, he was a member of the committee founded in 1866 to prosecute Edward Eyre, governor of Jamaica [see Jamaica committee]. Beesly and other positivists incurred hostility for advocating intervention on the side of France in the Franco-Prussian War, and for defending the Paris commune. Their republican views found expression not only in the press but also at the positivist centre in Chapel Street (now Rugby Street) that they opened in 1870 under Congreve's direction. There they introduced sacraments of the Religion of Humanity and published a co-operative translation of Comte's Positive Polity.[1] When Congreve repudiated their Paris co-religionists in 1878, Beesly, Harrison, Bridges, and others formed their own positivist society, with Beesly as president, and opened a rival centre, Newton Hall, in a courtyard off Fleet Street. Beesly headed its political discussion group, which produced occasional papers. Retirement from University College in 1893 (he had left Bedford College in 1889) enabled him to found and edit the Positivist Review.[1]

In 1881, Beesly attended the early meetings of the Democratic Federation, but he was soon marginalised, and returned to the Liberal Party by the middle of the decade.[2]

In 1869 Beesly married Emily, youngest daughter of Charles John Crompton, justice of the queen's bench, and his wife, Caroline. The Beeslys lived in University Hall until 1882, when they moved to Finsbury Park. Mrs Beesly was not a positivist—as were her brothers Albert and Henry Crompton—but she shared some of her husband's political and historical interests. He unsuccessfully stood for parliament as a Liberal at Westminster in November 1885 and at Marylebone in July 1886.[1] Emily Beesly became president of the women's liberal association of Paddington after their move to Warrington Crescent in 1886. Both advocated Irish home rule, he in hard-hitting articles, she in new lyrics for The Wearing of the Green. In 1878 he published Catiline, Clodius, and Tiberius, and she brought out her Stories from the History of Rome, written for their four sons. She died in 1889, aged 49.

Beesly's later publications included seventy-four biographical entries on military and political figures for the positivists' New Calendar of Great Men, and Queen Elizabeth, both of which appeared in 1892. In 1901 he retired to 21 West Hill, St Leonards, Sussex, where he published translations of Comte and continued to write for the Positivist Review.[1] He died at home on 7 July 1915 and was buried in Paddington cemetery. He left a name still honoured by labour historians.

Friends

Beesly was not only friendly with Marx, but was well acquainted with his circle. He knew Lafargue, he got to know Engels, and there were mutual acquaintances, such as Eugene Oswald. Among workmen, he was not only the friend of George Odger, Robert Applegarth and Lucraft, but was on close terms with such working-class confidants of Marx as Jung and Eccarius, and to a lesser extent with Dupont. In the sixties he was a familiar figure, not only in the offices of the Carpenters and Joiners, the London Trades Council or The Bee-Hive, but was also at home in the "Golden Ball" where the most radical of London's workmen talked with continental revolutionaries over a clay pipe and a pot of beer. Here one could get the flavour of European proletarian politics: that other “World of Labour” in whose ideals Beesly was as deeply interested as he was in those of English trades unionism. Indeed, for many years he expressed his desire for the amalgamation of trade unionism – with its implicit recognition of the priority of social questions—, and proletarian republicanism – with its generous enthusiasm and its larger view.

Letter from Marx

Auction lot description of Beesly's copy of Das Kapital: This is an excellent association copy, inscribed to Karl Marx's friend Professor Edward Spencer Beesly (1831–1915), positivist of the Auguste Comte school of thought, historian, and one of the founding editors of the Fortnightly Review. In 1868, when Marx & Engels were trying to develop international momentum for the economic philosophy contained in this work, they contacted the Fortnightly Review via Beesly to see if it would be interested in publishing a critique of Das Kapital; at the time Marx wrote to Engels: "Prof. Beesly, who is one of the triumvirate which secretly runs this rag, has… declared, he is 'morally certain' (it depends on him!) a criticism would be accepted" [8 January 1868]. An eventual review was passed on to the then chief editor John Morley by Beesly, but Morley apparently found the piece unreadable and would not allow publication, even after Beesly had suggested Marx could try to make the article less dry and more popularist in tone. Beesly subsequently suggested Marx & Engels contact The Westminster Review, but nothing seems to have come of this either. The further inscription, possibly by Beesly, reads "Died 14 March 1883", the date of Marx's death. Sold for £115,000, 27 May 2010

An inscribed copy of Das Kapital from Karl Marx to Edward Spencer Beesly

An inscribed copy of Das Kapital from Karl Marx to Edward Spencer Beesly An inscribed copy of Das Kapital from Karl Marx to Edward Spencer Beesly

An inscribed copy of Das Kapital from Karl Marx to Edward Spencer Beesly A letter from Karl Marx to Prof. Edward Spencer Beesly

A letter from Karl Marx to Prof. Edward Spencer Beesly The Positivist Review

The Positivist Review

References

- Chisholm 1911.

- Breuilly, John; Niedhart, Gottfried; Taylor, Antony (1995). The Era of the Reform League: English Labour and Radical Politics 1857–1872. Mannheim: J & J Verlag. p. 334.

Sources

- Bevir, Mark. 2011. The Making of British Socialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 644.

- Claeys, Gregory. 2018. "Professor Beesly, Positivism and the International: the Patriotism Issue". In "Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth": The First International in a Global Perspective, edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quinton Deluermoz and Jeanne Moisand. Leiden: Brill.

- Claeys, Gregory. 2010. Imperial Sceptics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Royden. 1959. "E. S. Beesly and Karl Marx, IV–VI". International Review of Social History 4 (1):208–38.

- Harrison, Royden. 1959. "E.S. Beesly and Karl Marx, I–III". International Review of Social History 4 (1):22–58.

- Harrison, Royden. 1965. Before the Socialists. London: Routledge.

- Harrison, Royden. 1967. "Professor Beesly and the Working-class Movement". In Essays in Labour History, edited by Asa Briggs and John Saville, 205–41. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harrison, Royden, ed. 1971. The English Defence of the Commune, 1871. London: Merlin.

- Kent, Christopher. 1978. Brains and Numbers: Elitism, Comtism, and Democracy in mid-Victorian England. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Kent, C. 'Beesly, Edward Spencer', BDMBR, vol. 2

- Liveing, Susan. 1926. A Nineteenth-Century Teacher: John Henry Bridges. London: Paul.

- McGee, John Edwin. 1931. A Crusade for Humanity: the History of Organized Positivism in England. London: Watts.

- Porter, Bernard. 1968. Critics of Empire. London: Macmillan.

- Royle, Edward. 1974. Victorian Infidels. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- The Times (9 July 1915), 11d · Positivist Review, 23 (1915) [with bibliography] ·

- C. L. Davies, The Spectator (17 July 1915), 77–8 ·

- Sociological Review, 8 (July 1915), 187–8 · Foster, Alum. Oxon.

- Vogeler, Martha S. 1984. Frederic Harrison: the Vocations of a Positivist. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Wilson, Matthew. 2018. Moralising Space. London: Routledge.

- Wright, T.R. 1986. The Religion of Humanity: the Impact of Comtean Positivism on Victorian Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archives

- UCL, corresp., lecture notes, and papers mainly relating to historical interests | Bishopsgate Institute, London, letters to George Howell · BL, corresp. with Richard Congreve, Add. MS 45227 · BL, Positivist MSS · BLPES, corresp. with Frederic Harrison · BLPES, London Positivist Society MSS · Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Amsterdam, letters to Karl Marx · Maison d'Auguste Comte, Paris, letters to Constant Hillemand and others · Yale University, Beinecke Library, letters to George Eliot

External links

Quotations related to Edward Spencer Beesly at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Edward Spencer Beesly at Wikiquote- Works by or about Edward Spencer Beesly at Internet Archive

- Works by Edward Spencer Beesly at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)