Edward Kerling

Edward John Kerling (June 12, 1909 – August 8, 1942) was a spy and saboteur for Nazi Germany and the leader of Operation Pastorius during World War II.

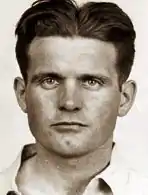

Edward John Kerling | |

|---|---|

FBI mugshot (1942) | |

| Born | June 12, 1909 |

| Died | August 8, 1942 (aged 33) |

| Cause of death | Execution by electrocution |

| Resting place | Washington Asylum Potters Field |

| Other names | Eddie Kerling |

| Political party | Nazi Party |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Spouse | Marie Sighard |

| Conviction(s) | Acting as unlawful combatants with the intent to commit sabotage, espionage, and other hostile acts Aiding the enemy as an unlawful combatant Espionage Conspiracy |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Title | Espionage activity |

| Allegiance | |

| Service branch | Wehrmacht Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda |

| Service years | 1940–1942 |

| Operations | Operation Pastorius |

Early life

Born in Biebrich, Wiesbaden, Kerling was the son of Kasper and Walberoa Kerling. His father, Kasper, was a World War I Imperial German Army veteran. Kerling studied engineering at the University of Freiburg. He joined the Nazi Party in 1928.[1] After leaving school, he went to the U.S. and over the next several years worked a myriad of jobs. He married Marie Sighard in 1931. Kerling and Sighard frequently travelled back to Germany throughout the years to visit their families. The couple was estranged by the time of Operation Pastorius, with both being in other relationships.[2]

World War II

In the summer of 1940, Kerling once more returned to Germany to look for work. He received a position within the Wehrmacht translating English broadcasts into German. He was sent to France for the duration of the project and returned to Berlin after three months. Upon returning, Kerling was given a position with the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda managing German theatres. He remained with the Propaganda Ministry for the next two years until Walter Kappe offered him the chance to return to the U.S. on a military mission. After a short time Kerling accepted the offer and spent the next several weeks training and becoming acquainted with other members of the mission. He spent a great deal of time with his parents during this period.[2]

Operation Pastorius

Operation Pastorius consisted of 12 Germans who were fluent in English. They were trained as secret agents at the Brandenburg School of Sabotage. Upon graduation they were sent to the U.S. via U-boat in an attempt to damage infrastructure and industries vital to the American war effort. Kerling's group landed on Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida on June 17, 1942.[2]

Kerling was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation on June 23, 1942. It was revealed that two members of the other group, George Dasch and Ernst Burger, betrayed the entire operation and alerted federal authorities of their intentions.[3]

Trial and death

Kerling and the seven others involved were sent to Washington, D.C., where they were to face a military tribunal. All were convicted of being spies and, even though they had not yet carried out any sabotage, six — including Kerling — were sentenced to death.[4] Dasch and Burger received long prison sentences which were eventually commuted to deportation after the war.[3]

Kerling and the remaining five, Herbert Hans Haupt, Henry Harm Heinck, Hermann Otto Neubauer, Richard Quirin, and Werner Thiel were all executed on August 8, 1942, in the District of Columbia's electric chair.[5] It was the largest mass execution via electrocution ever conducted at the jail. Kerling and the others were buried in the Potter's Field in Blue Plains. The graves were originally marked by boards with numbers until a German-American organization placed a small monument commemorating their lives.[3]

Prior to his execution, Kerling wrote a final letter to his wife:

"Marie, my wife—I am with you to the last minute! This will help me to take it as a German! Even the heaven out there is dark. It’s raining. Our graves are far from home, but not forgotten. Marie, until we meet in a better world! May God be with you. My love to you, my heart to my country. Heil Hitler! Your Ed, always."[6]

Other prosecutions

Four people were arrested for associating with Kerling in relation to the plot: His friend, Helmut Leiner, his girlfriend, Hedwig Engemann, his estranged wife, Marie Sighard, and Marie's boyfriend, Ernest Herman Kerkhof.[7][8][9][10]

Leiner was charged with treason for agreeing to get change for two 50 dollar bills for Kerling. He was acquitted since he was not an American citizen, but was then immediately interned. In 1943, Leiner pleaded guilty to three counts of trading with the enemy and was sentenced to 18 years in prison. He was paroled in 1954. Engemann was also suspected of exchanging money for Kerling, but there was only enough evidence to charge her with misprision of treason. The charge was for having knowledge about Leiner's trading and not intervening. Engemann pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three years in prison. She was paroled in April 1945.[7][8]

While they were both interned for the remainder of the war, neither Sighard nor Kerkhof were ever charged due to a lack of evidence. While both were members of the pro-Nazi German American Bund, there was no other evidence against Kerkhof, and the only evidence against Sighard was that Leiner had attempted to arrange a meeting between her and Kerling.[9][10]

See also

Citations

- Cohen, Gary (February 1, 2002). "The Keystone Kommandos". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- Kerling, Edward; Kerling's Confession

- FBI, National Socialist Saboteurs

- Ex Parte Quirin

- National Socialist Saboteur Trial

- "Last Words of the Executed". Retrieved March 5, 2023.

- Spark, Washington Area (July 1, 1942), Man who aided Nazis initially acquitted: 1942, retrieved March 5, 2023

- Spark, Washington Area (July 1, 1942), Saboteur's lover charged with misprision of treason: 1942, retrieved March 5, 2023

- Spark, Washington Area (July 1, 1942), Nazi saboteur's wife detained: 1942, retrieved March 5, 2023

- Spark, Washington Area (July 1, 1942), Nazi saboteur's wife's lover detained: 1942, retrieved March 5, 2023

References used

- Kerling, Edward. "Kerling's Confession". twin-cities-umn.edu. Retrieved October 23, 2020.</ref>

- "National Socialist Saboteurs". fbi.gov. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "Ex Parte Quirin". law.cornell.edu. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- "National Socialist Saboteur Trial". loc.gov. Retrieved October 24, 2020.