Educational inequality in the United States

Unequal access to education in the United States results in unequal outcomes for students. Disparities in academic access among students in the United States are the result of several factors including: government policies, school choice, family wealth, parenting style, implicit bias towards the race or ethnicity of the student, and the resources available to the student and their school. Educational inequality contributes to a number of broader problems in the United States, including income inequality and increasing prison populations.[1] Educational inequalities in the United States are wide-ranging, and many potential solutions have been proposed to mitigate their impacts on students.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

| Summary |

|

| Issues |

| Levels of education |

|

|

|

History

Colonial era

The earliest forms of education in the U.S. were primarily religiously motivated. The main purpose of education in the 17th and 18th was to teach children how to read the bible and abide by Puritan values.[2][3] These values were espoused by religious white colonists, who would often try to assimilate indigenous children into white puritan standards and convert them to Christianity. The purpose of formal education for indigenous peoples was to enforce assimilation/acculturation into European and Christian standards.[4] Through the process of assimilation, indigenous populations were often forced to give up cultural traditions, including their native language. Forced assimilation would continue past colonial times. In the early 20th century, indigenous children in certain regions of the U.S. were forcibly taken from their families and enrolled in boarding schools.[5][6] The purpose of this was to "civilize" and assimilate indigenous communities into American society.

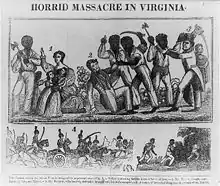

Historically, African-Americans in the United States have also had several troubles trying to access quality education. In colonial times, many white people felt that if Black people, slaves in particular, were to become educated they would start to challenge the systems of power that kept them oppressed.[7] Southern states feared slaves would begin to act out against their slave owners and/or escape to Northern states if they were educated. This caused several states to enact laws that prohibited slaves from learning to read or write. These were popularly referred to as anti-literacy statutes. Although punishment varied from state to state, several southern states (Virginia, South Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia) would criminally prosecute any slave who attempted to learn to read or write.[8] In some cases, white people could also be punished for attempting to educate slaves. Religious groups in certain communities would attempt to make schools for African-Americans to read or write, but it was often met with severe opposition from white community members.

Civil War and Reconstruction era

The Civil War and the emancipation of slaves led to a push for more education of African-Americans. Most Black people did not have access to education until the Reconstruction era following the Civil War, when public schools started to become more common.

Newly freed African-Americans prioritized education, and many considered it an effective way to empower their communities. In Southern states, Black residents would engage in collective action and collaborate with the Freedmen's Bureau, northern philanthropic organizations, and other white groups to ensure their access to public education.[9] During the Reconstruction Era the enrollment of Black students began to increase because of the increased population of freed blacks.[10]

Although the enrollment rate of Black students would increase from that point in time onward, there is still evidence of unequal achievement between white students and students from non-white racial identities, as well as between students from low socioeconomic backgrounds and students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds.[11]

Jim Crow era

During the Jim Crow time, schools were still segregated, which would often result in Black schools receiving less funding. This meant Black students were educated in worse facilities, with fewer resources and less well-paid teachers than their white counterparts. Furthermore, under Jim Crow, segregation had many negative effects that are seen today. For example, since segregated schools had fewer resources, less experienced teachers, and overall less funding there was a lower expectation for student academic achievement. This academic achievement gap is something that is still seen in the 21st century.(1. Furthermore, due to the nature of the environment at the time, there were increased dropout rates for black students in these segregated schools. This can limit their future employment opportunities and perpetuate a cycle of poverty and inequity. Furthermore, Fewer African-American students would enroll in school than their white counterparts and they had less public schools available to them. The majority of Black students would not continue their education past an elementary school level.[12]

In Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) it was decided that educational facilities were allowed to segregate white students from students of color as long as the educational facilities were considered equal. In practice, separate educational facilities meant fewer resources and access for Black and other minority students. On average white students received 17–70 percent more educational expenditures than their Black counterparts.[13] The first Federal legal challenge of these unequal segregated educational systems would occur in California Mendez v. Westminster (1947) followed by Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

To further elaborate, Brown v Board of Education was a landmark Supreme Court case that declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. This decision was issued on May 17, 1954, by the United States Supreme Court. The case was brought by the NAACP in order to challenge segregation in Kanas, which prohibited African Americans from attending white schools.The Court held that segregation in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees all citizens the same protection under the law. It held that segregation perpetuated feelings of inferiority among African American children and hindered their abilities to learn, and therefore ordered the integration of schools. It's important to note that the Brown decision served as a catalyst for the civil rights movement.Brown V Board of Ed

Integration

In the United States, integration is the process of ending race-based segregation within public and private schools, and it is generally referred to in the context of the Civil Rights Movement. Integration has historically been employed as a method for reducing the achievement gap which exists between white and nonwhite students in the United States.[14] Students in integrated schools also learn to be more accepting of others. This has been shown to reduce prejudice on the basis of race.[15]

Studies conducted in schools across the country have found that racial integration of schools is effective in reducing the achievement gap.[16] In 1964, in accordance with the Civil Rights Act of that year, the United States Congress commissioned sociologist James Coleman to direct and conduct a study on school inequality in the U.S. The report, known colloquially as the Coleman Report, was a landmark study in the field of sociology and education. The report detailed the extreme levels of racial segregation in schools which still persisted in the Southern United States despite the ruling of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education. Coleman found that Black students benefited greatly from learning in mixed-race schools. Therefore, Coleman argued that busing Black students to white school districts to integrate would be more effective in reducing the disadvantages of Black students as opposed to an increase in funding which the report had discovered impacted student achievement very little.[17] These findings would serve as an influential factor in the creation of the practice known as desegregation busing.[18]

Factors contributing to inequalities

Race

Race is often a big contributor to inequalities in education, and it can explain the widening achievement and discipline gaps between white students and students of color. Implicit bias and stereotyping perpetuate systemic injustices and lead to unequal opportunities.

Race influences teachers' expectations and in turn, influences achievement results. A 2016 study showed that non-Black teachers had much lower expectations of Black students than Black teachers who evaluated the same student. White teachers were 12% less likely to think the student would graduate from high school and 30% less likely to think they would graduate from college.[19] Previous studies have proved the importance of teachers' expectations: students whose teachers believe they are capable of high achievement tend to do better (Pygmalion effect).[20] In another study, it was found that white teachers were more likely to give constructive feedback on essays if they believed the student who wrote it was white. Essays perceived to be written by Black or Latino students were given more praise and less guidance on how to improve their writing.[21] One reason for this lack of quality feedback could be that teachers don't want to appear racist so they grade Black students more easily; this is actually detrimental and can lead to lower achievement over time.[22]

One research study done to look at how implicit bias affects students of color found that white teachers who gave lessons to Black students had greater anxiety and delivered less clear lectures. They played recordings of these lectures to non-Blacks students who performed just as badly, proving that it wasn't a result of the students' ability but rather implicit bias in the teachers.[23]

Non-Asian minority students often don't have equal access to high-quality teachers which can be an indication for how well a student will perform.[24] However, there has been conflicting research on how large the effect truly is; some claim having a high-quality teacher is the biggest predictor of academic success[25] while another study says that inequalities are largely caused by other factors.[24]

White supremacy in curriculum

A range of scholars from at least the late 19th century to the present have produced arguments that white supremacy exists in U.S. school curriculum, oftentimes to the detriment of non-White students Americans' learning outcomes and the whole of American society. In the early 20th century, Historian Carter G. Woodson argued that U.S. education indoctrinated students into believing White people were superior, and Black people inferior, by showcasing White accomplishments and effectively denying that Black people had made any contributions to society or had any potential.[26] In his experience, the racial message contained in schools' teachings was so strong that he made the claim, "there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom."[26] More recent scholarship still points to the overrepresentation of perspectives, histories, and accomplishments associated with European and White American culture, and the simultaneous underrepresentation of the perspectives, histories, and accomplishments of non-White Americans'.[27][28][29] Swartz (1992) and King (2014) describe school curriculum has been structured by what they call a masternarrative.[30][31] Swartz defines this term as an account of reality that advances and reaffirms White people's dominance in American society through the centering of White achievements and experiences, while consistently omitting, simplifying, and "distorting" non-White peoples (p. 341-342).[31]

As an example, Powell and Frankenstein (1997) draw attention to Eurocentrism in the field of mathematics, arguing that the critical advancements made in societies outside of Europe, including Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, India, and China, are very frequently ignored in the narrative that the Ancient Greeks pioneered most math, which Europe then later salvaged after the Dark Ages.[32] In her analysis of American history textbooks, Swartz (1992) highlights a repeated failure to provide meaningful information about Black Americans, namely throughout slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights Movement. Instead, textbooks often frame slavery and other issues in ways that encourage sympathy with White Americans, including slave-holders. Multiple textbooks include discussions of slave revolts in terms of the damage they caused White people instead of focusing on the need of enslaved Black people to overthrow the system of slavery (pp. 346–347).[31] Other scholars, including Brown (2014), Elson (1964) Huber et al. (2006), Mills (1994), and Stout (2013) have argued that Black people,[33] Native Americans,[28] East Asian and Southeast Asian Americans, and Mexican Americans have been subject to marginalization, silencing, or misrepresentation in U.S. school curriculum.[34][29][35]

Other scholars have argued that White (and also middle-class) cultural norms are employed in the creation and delivery of school curriculum, to the detriment of students who do not have the same cultural background. Crawford (1992) writes that White American values such as "competition," "confrontation"[12] structure class proceedings when students with different upbringings may be uncomfortable with or confused by these conventions. The same is true, she argues, for activities such as group work and engaging in dialogues with the teacher, rather than perhaps receiving information silently.[36] Crawford also asserts that oftentimes schools do not look to conform to their students' specific life circumstances, thereby obstructing these students' educational paths (p. 21).[36] Hudley and Mallinson (2012) discuss the use of "standardized English" in schools and how that impacts students, who speak a wide range of types of English. "Standardized English" refers to the version of English used in American academia and professional settings, which is also the type of English spoken by middle-class White Americans (pp. 11–12). The authors cite a consensus among linguists that there is no objective standard for English, and that in reality, standardized English has been judged to be "standard" because it is what is spoken by people who wield power in society (p. 12). They emphasize that children who grow up speaking standardized English enjoy linguistic privilege when both when learning how to read and write, when interacting with teachers. At the same time, students who grow up speaking with different English conventions suffer stigmatization due to their speech patterns and experience the added difficulty of having to learn a whole new set of language conventions while participating in "normal" schoolwork (p. 36). The authors hold that by holding minority students to historically White English norms, schools often communicate that these students must make themselves whiter to be seen as acceptable. This is potentially true for African American Vernacular-speaking students in particular (p. 36).[37]

Effects

Crawford (1992) and Hudley and Mallinson (2012) state that non-white students may struggle in school and in life due to their races' and cultures' marginalization in curriculum.[36][37] Other scholars have raised concerns about the lack of opportunities to see themselves as having academic or professional potential.[26][38] These authors assert that lack of meaningful use and discussion of non-white perspectives, practices, and feats may lead minority students to feel disillusioned with school, to disengage from learning, and to doubt their own capabilities.[26][36][37][38] In a study on internalized racism, Huber et al. (2006) find that curriculum underrepresents minorities and that this may contribute to engrained senses of racial inferiority (p. 193).[35]

Citing the issues above, Hudley and Mallinson (2012) and Fryer (2006) discuss the development of a stigmatizing label of "acting white" used by some Black and Hispanic students.[37][39] According to these authors, the phenomenon of "acting white" comes from seeing academic success as coming hand in hand with whiteness, or for some non-white students, the abandonment of their original cultures in order to succeed in a White-culture-normative society.[37] In this case, academic success is coupled with accepting the Eurocentric practices used by schools, which means self-disenfranchisement.[37] This social stigma of "acting white" may discourage strivings for academic success among Black and Hispanic students.[39][37] Fryer (2012) explains that Hispanic students' popularity starts to decline relative to their grade point average after they attain a 2.5; for Black students, this number is a 3.5; for White students, this relationship does not appear to occur.[39]

At the societal level, white supremacy in curriculum may contribute to the perpetuation of white supremacy, affecting future generations.[40][35] Huber et al. (2006) notes that Euro- or white-centric curriculum can contribute to the normalization of racial inequality and tolerance of White dominance (p. 193).[35] Brown and Brown (2010) also state that if schools continue to not teach about systemic racism, students will grow up to be "apathetic" about Black victims of mass incarceration and gun-related violence, as well as the disproportionate suffering experienced by Black Americans after natural disasters (p. 122).[41]

Socioeconomic status

In the United States, a family's socioeconomic status (SES) has a significant impact on the child's education. The parents' level of education, income, and jobs combine to determine the level of difficulty their children will face in school. It creates an inequality of learning between children from families of a high SES and children from families of a low SES. Families with a high SES have the ability to ensure their child receives a beneficial education while families with a low SES usually are not able to ensure the same quality education for their child. This results in children of less wealthy families performing less well in schools as children of wealthier families. There are several factors that contribute to this disparity; these factors narrow into two main subjects: resources and environment.

The type of environment a student lives in is a determinant of the education they receive. The environment a child is raised in shapes their perceptions of education. In low SES homes, literacy is not stressed as much as it is in high SES homes. It is proven that wealthier parents spend more time talking to their children and this builds up their vocabulary early on and enhances their literacy skills.[43] In a study from the NCES, outside school, parental involvement grows exponentially as the household income grows. It shows that parents making $100k a year or more were 75% likely to tell a story to their child where as a family making $20k is only 60% likely to tell their child a story.[44] These types of activities are what leads to brain development and kids with lower SES are statistically receiving less. Children of low SES are also exposed to a more stressful environment than higher SES children. They worry about influences a lack of money in the household could create (such as bills and food). This stress manifests itself all throughout a students learning career. We see statistically that students coming from higher poverty areas graduate college at nearly half the rate of students from a lower poverty school.[45]

There is great variation in the resources available to children in schools. Families of higher SES are able to invest more into the education of their children. This ability manifests in the popular tactic of shopping around school districts: parents plan where they are going to live based on the quality of the school district. They can afford to live in areas where other families of high SES reside, and this congregation of high-SES families produces a school district that is well funded. These families are capable of directly investing in their children's education by donating to the school. Having access to such funds gives the schools capacity to hold high caliber resources such as high-quality teachers, technology, good nutrition, clubs, sports, and books. If students have access to such resources, they are able to learn more effectively. Children of lower SES families do not have such resources. A timely example shown in the NCES study is that of home internet access by median income and race. We see, by a large margin, Black and Hispanic students having the least access to the internet along with those of the lowest median income quarter.[46] These low SES families settle down where there is an availability of jobs, and are less able to shop around school districts. Clusters of low-SES families typically are within worse school districts. The families are not in a position to donate to their children's school and the schools lack appropriate funding for good resources. This results in schools that cannot compete with wealthier schools.[47][48] However, recent political developments favor legal changes to these funding laws. For example, a court in Pennsylvania held the state's funding processes as failing to uphold the state's constitutional obligation in providing education.[49]

Neighborhood effects

Neighborhoods play a significant effect on the development in adolescents and young adults. As a result, much research has studied how neighborhoods can explain a person's level of educational attainment. These findings are highlighted below.

Research has shown that an adolescent's neighborhood can significantly affect his or her life chances.[50] Children from poorer neighborhoods are less likely to climb out of poverty compared to children who grow up in more affluent neighborhoods. In terms of education, students from neighborhoods with a high SES have higher levels of school readiness and higher IQ levels. Studies have also shown that there are "links between neighborhood high SES and educational attainment" in regards to older adolescents.[51] Children growing up in high SES neighborhoods are more likely to graduate from high school and attend college compared to students growing up in low SES neighborhoods. Living in a low SES neighborhood has many implications in terms of education. Among them are "greater chances of having a child before age 18; lesser chances of graduating from high school; and earning lower wages as a young adult. Experiencing more neighborhood poverty as a child is also associated with a lower rate of college graduation."[52]

The neighborhood effect is mitigated when students who grow up in low SES neighborhoods move to high SES neighborhoods. These students are more likely to reap the same benefits as students in high SES neighborhoods and school systems; their chances of attending college are much higher than those who stayed in low SES neighborhoods. One study done in Chicago placed African Americans students in public housing in the suburbs as opposed to in the city. The schools in the suburbs generally received more funding and had mostly white students attending. Students who attended these schools "were substantially more likely to have the opportunity to take challenging courses, receive additional academic help, graduate on time, attend college, and secure good jobs."[53]

Private vs. public education

There are several differences in how private schools operate when compared to public schools. Public schools are funded by federal, state and local sources with nearly half of their funding coming from local property taxes.[54] Private schools are funded from resources outside of the government, which typically comes from a combination of student tuition, donations, fundraising, and endowments. Private school enrollment makes up about 10 percent of all K-12 enrollment in the U.S (about 4 million students),[55] while public school enrollment encompasses 56.4 million students.[56]

Because private schools are funded outside of government channels, they often exercise more freedom in how they operate their schools. Many private schools choose to teach material outside of the state-mandated curriculum. They are also allowed to have religious affiliations and selection criteria for which students they accept. In contrast, public schools are not allowed to have religious ties and must accept any student that is geographically zoned in their area. There have been several arguments that have been raised against private school systems. Some argue that it perpetuates elitist forms of education, and has high barriers to entry, as tuition to private schools can be up to tens of thousands of dollars. For reference, the national average cost of private school tuition in the 2020–2021 school year is $11,004.[57] Since several private schools have religious affiliations, there have also been arguments regarding potential bias and questionable standards in religious private schools.[58]

Differences in private vs public education can have effects on the future achievement of children. Several studies point out the fact that students who attend private schools are more likely to graduate from high school and attend college afterward.[59] There have been studies that point to the fact that areas where a homogenous public education system is present have higher amounts of inter-generational social mobility. In comparison, private education systems can lead to higher inequality and less mobility.[60] The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth has also pointed to the fact that students who attend private schools tend to earn more in their careers than compared to their public school counterparts.

Language barriers

As of 2015, there are nearly 5 million English language learner (ELL) students enrolled in U.S. public schools and they are the fastest-growing student population in the U.S.[61] About 73% of ELL students speak Spanish as their first language, although the most common language will vary by state. 60% of English language learner students come from low-income families, where parents have very limited educational levels. Family income level and lack of English language skills are often two challenges that are intertwined in the barriers that ELL students face.

Students who are not proficient in English are put at a serious disadvantage when compared to their peers. There is a strong association between English-language ability and the success of students in school. ELL students have disproportionately high dropout rates, low graduation rates, and low college completion rates.[62]

A potential cause of ELL students' lack of achievement is communication difficulties that can arise between student and teacher. Many educators may treat students with low English proficiency as slow learners or intellectually disadvantaged.[63] There is evidence that a potential consequence of this lack of understanding on the educator's side is the creation of a self-fulfilling prophecy: teachers treat students as less capable and students internalize these expectations and underperform.[64] These students may also feel a cultural conflict between their native language and English. Cultural differences may cause students to feel a rejection of their native culture/language leading to a decrease in motivation in school. Most experts agree that it takes students around 5–7 years to learn academic English, which in a school setting can place students learning English behind their English-speaking classmates.[65] Many people who speak little English may face language barriers when seeking health care. This article describes what is currently known about language barriers in health care and outlines a research agenda based on mismatches between the current state of knowledge of language barriers and what health care stakeholders need to know. In each of these areas, specific research questions and recommendations are outlined.[66] Different people use language in different ways. We capture this by making language competence—the set of messages an agent can use and understand—private information. Our primary focus is on common-interest games. Communication generally remains possible; it may be severely impaired even with common knowledge that language competence is adequate.[67] It shows the language barriers may be more important to international trade then previously thought. The language barrier index, a newly constructed variable that uses detailed linguistic data, is used to show that language barriers are significantly negatively correlated with bilateral trade.[68] A language barrier impedes the formation of interpersonal relationships and can cause misunderstandings that lead to conflict, frustration, offense, violence, hurt feelings, and wasting time, effort, money, etc. It is also a figurative phrase used primarily to refer to linguistic barriers to communication, i.e., the difficulties in communication experienced by people or groups originally speaking different languages, or even dialects in some cases.

Educational inequalities

K-12

Education at the K-12 level is important in setting students up for future success. However, in the United States there are persisting inequalities in elementary, junior high, and high school that lead to many detrimental effects for low-income students of color.

One indicator of inequality is that Black children are more likely to be placed in special education. Teachers are disproportionately identifying African American students for developmental disorders: Black students "are about 16% of the school-age population yet are 26% and 34% of children receiving services under the SED [serious emotional disturbances] and MMR [mild mental retardation] developmental delay categories."[69] On the other hand, ADHD in Black children is more likely to go undiagnosed, and as a result, these students are often punished more severely than white students who have been recognized as having ADHD.[70] One study shows that Black students with undiagnosed ADHD are seen as disruptive and taken out of class, reducing their learning opportunities and increasing the chances they will end up in prison.[70]

More evidence of inequality is that allocation of resources and quality of instruction are much worse for African American, Native American, and Latino students when compared to their white counterparts.[53] An analysis by the Stanford University School of Education found that there is a high concentration of minority students in schools that are given fewer resources like books, laboratories, and computers. In addition, these schools often have larger student to teacher ratios and instructors with fewer qualifications and less experience. Teachers who are unqualified and inexperienced are less likely to adapt to different learning methods and fail to implement higher-order learning strategies that constitute quality education.[53] Students who are placed in gifted education often receive better instruction; it was discovered that Black children were 54% less likely to be placed in one of these programs and "were three times more likely to be referred for the programs if their teacher was Black rather than white."[71]

According to multiple studies, African American students are disadvantaged from the very beginning of elementary school.[72] One survey reported that they have very high aspirations (much higher when compared to the white students) but usually face negative schooling experiences that discourage them.[73] These disparities carry over into higher education and explain much of why many choose not to pursue a degree.[73]

Furthermore, in a 2006-07 research performed by the Institute of Education Sciences, statistics show that Black, Hispanic, poor, and near-poor students made up 10 percent of the population of total students who attended a public schools that did not meet Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP).[74]

Higher education

Higher education encompasses undergraduate and postgraduate schooling and usually results in obtaining a higher-paying job.[75] Not only do Black and Hispanic people have less access to universities, they face many inequities while they attend and while applying to postgraduate programs. For most of history, Black Americans were not admitted into these institutions and were generally dissuaded from pursuing higher education.[76] Even though laws have been enacted to make access to higher education more equal, racial inequalities today continue to prevent completely equal access.[76]

One study found that the social environment of universities makes African Americans feel more isolated and less connected to the school. They observed that "African American students at White institutions have higher attrition rates, lower grade point averages, lower satisfactory relationships with faculty, lower enrollment into postgraduate programs, and greater dissatisfaction."[72] Additionally, many researchers have studied stereotype threat which is the idea that negative perceptions of race can lead to underperformance.[77] One of these experiments done at Stanford tested a group of African Americans and a group of white students with the same measured ability; African Americans did worse when the test was presented as a measure of their intellect and matched performance of their white peers when they were told the test did not reflect intellectual ability.[78]

Other studies have been conducted to analyze the different majors that students choose and how these majors hold up in the job market. After analyzing data from 2005 to 2009, they saw that African Americans were less likely to major in a STEM-related field, which has a higher return on investment than the liberal arts.[75] A 2018 study yielded similar results: white students are twice as likely to major in engineering than Black students, with Hispanic students also being underrepresented.[79]

In regards to postgraduate study, Black students are less likely to be accepted into such programs after college.[72] One possible reason is because they aren't being recruited for doctoral programs and are looked upon less favorably if they received a degree from an HBCU (historically black colleges and universities).[72]

Achievement gap

The achievement gap describes the inconsistencies in standardized test scores, rates of high school and college completion, grade point average between different ethnic-racial groups in the United States.[80] It is significant because White students tend to achieve far more academically compared to Black and Latino students.[81] Latino and Black students have some of the lowest college school completion rates in the United States. On average, they also have lower literacy rates in school and lag behind White students in terms of math and science proficiency.[82] It is important to understand that these discrepancies have long-term achievement effects on Latino and Black students.

There are several factors that can explain the achievement gap. Among some of the most studied and popular theories are that predominantly Black/Latino schools are concentrated in low SES neighborhoods that do not receive adequate resources to invest in their student's education (such as the ability to pay for qualified teachers) and that parental participation in Black and Latino families lags behind White families.[83] Family influence is significant as shown in a study that demonstrated how high levels of parental involvement in low income communities can actually assist in mitigating the achievement gap.[84]

Summer learning gap

An imbalance in resources at home creates a phenomenon called the summer learning gap. This exhibits the impact of resources outside of school that influence a child's education progression. It uncovers a troubling contrast between the growth in math skills over the summer between children of high SES and children of low SES.[47]

The graph displaying the summer learning gap shows the higher SES children starting above the lower SES children at year one. The higher SES children are already ahead of the lower SES children before grade school even starts because of the amount of resources available to them at home. This may be due to their early introduction into literacy and higher vocabulary due to the higher amount of words they are exposed to as mention in a previous paragraph. Also, the lower SES children's access to books is solely through school, and their reading skills are not developed at all at year one because they have not had the exposure yet.

As the graph goes on, it is evident that the two groups of children learn at the same rate only when they are in school. The higher SES students are still above the lower SES students because the rate of learning of the children changes radically during the summer. In the summer, the higher SES children show a very slight increase in learning. This is due to their access to various resources during the summer months. Their families are able to enroll them in summer enrichment activities such as summer camp. These activities ensures that they are still being educationally stimulated even when not in school. While at the same time, lower SES students show evidence of a slight decrease in learning during the summer months. Lower SES students do not have the same opportunities as the higher SES students. During the summer, these students are not focused on learning during the summer. Their parents do not enroll them in as many summer activities because they cannot afford them and so the children have more autonomy and freedom in those three months. They are concerned with having fun, and thus forget some of what they gained during the school year. This continuing disparity from year to year results in an approximately 100 point difference in their math scores at year six.[85]

Summer learning gap programs

Summer programs have been used as a method to decrease the achievement gap in American public schools. Many programs are free or at a reduced cost which make them more accessible. There are a wide range of programs provided by local school districts, non-profit organizations, or receiving federal funding to operate.[86] Some programs are required or mandated by school districts. There are also programs that are costly and only students from higher socioeconomic status are able to attend. Programs usually are for several weeks over the summer. There are programs students can participate in at home. The majority of summer programs focus on improving math and reading skills since those are the two subjects students are struggling with the most when looking at national test scores.[87] Reading programs that take place over the summer are often provided by local school districts with the purpose of boostiing students' interest in books. The books are provided by schools which make them accessible. Summer programs that focus on improving the summer learning gap focus on retaining the knowledge that students have gained through the academic year. Programs will have a lot more instructional time within their programming to help boost students' skills. Since these programs are able to have smaller class sizes, focus on individual students' needs, and provide students with a lot more attention, they foster a better learning environment.[88]

The accessibility to programs is a concern of many, since not all students have access to the same opportunities. Students who might not have access to summer programs may struggle more the following academic year.[87] Lack of access also increase the achievement gap that already exists between students from lower and higher socioeconomic status. While there are programs that are available that are low-cost or free, there is also the concern that the types of programs that come with a fee are better quality and provide a lot more to the students from higher income backgrounds.

The effectiveness of summer programs has been a growing concern. Programs that have been observed and produce positive results are available to students who are from lower socioeconomic status. While there is sufficient data that summer learning programs can be effective in some ways, there is also data on how it takes a while for these types of programs to actually make an impact on students.[86]

Discipline gap

The discipline gap refers to the overrepresentation of minority students among the differing rates of school discipline, especially in comparison to white students. Shifts in disciplinary policy have been attributed to the discipline gap, with African American students bearing the brunt of the subsequent inequalities. In recent decades, disciplinary policies meant to strengthen school control over social interactions, such as through the use of zero-tolerance, have been implemented, leading to a large increase of sanctions being levied against students.[89] Studies have also suggested that, for Black students, the likelihood of suspension increases in concordance with a rise in the population of Black students in a school's student body, as well as an increased likelihood of facing harsher punishments for behavior.[89] Additional research has suggested that African American students are both differentially disciplined and more likely to face harsher punishments relative to white students.[90] Furthermore, minority students are more often accused of subjective, rather than objective, disciplinary infractions.[91] Other minority demographics, such as Latinx and Native American students, face similar disproportionately high rates of school discipline—though relative to data about Black students, these findings have been less consistent.[90]

Explanations for the cause of the discipline gap are wide-ranging, as both broad factors and individual actions have been considered as potential sources of the gap. On a macrolevel, things like school culture have been suggested to be meaningfully associated with differences in suspension rates.[92] Conversely, a significant amount of research has been conducted on the micro-interactions that take place between teachers and students. The self-efficacy and confidence of teachers inherently influence their interactions with students, which can then shape their methods of classroom management and propensity to discipline students.[91] Moreover, preexisting assumptions or biases about students can also influence a teacher's treatment of their students.[93] Additional issues, such as cultural differences, have been identified as further complicating the relationship between teachers and students. Most notably, cultural misunderstandings between white teachers and Black students have been found to result in disciplinary action taken disproportionately against Black students.[89] Research has also indicated that the risk of cultural mishaps may be more pronounced among inexperienced or new teachers.[94]

Zero-tolerance policies

Zero-tolerance policies, also known as no-tolerance policies, were originally instituted to prevent school shootings by strictly prohibiting the possession of dangerous weapons in schools.[94] As these policies have proliferated nationally, research has shown that schools with large populations of minority students tend to utilize zero-tolerance more frequently relative to other schools, often in addition to the use of punitive disciplinary procedures.[95] Over time, these policies have gradually evolved from their original purpose and shifted towards meeting school-specific disciplinary goals, which has inadvertently contributed to the discipline gap.[94] In many schools, subjective misbehaviors—like disrupting the class or acting disrespectfully—have become offenses that are addressed by zero-tolerance.[95] This has resulted in negative consequences for minority students, as research has indicated that minorities tend to be disproportionately disciplined for subjective transgressions.[95] Additionally, zero-tolerance punishments can lead to student referrals to the juvenile detention system, even for offenses that may otherwise be considered minor.[94] The connection between zero-tolerance and juvenile detention has also been linked to other elements of the discipline gap, such as school-based arrests. Despite comprising approximately 15% of students, African Americans account for 50% of the arrests in schools.[96] While researchers have attributed many disciplinary policies to this disparity, zero-tolerance has been noted as a significant contributing factor.

Exclusionary policies

Exclusionary discipline policies refer to the removal, or 'exclusion,' of students from the classroom—typically in the form of suspensions or expulsions. The national emphasis on suspensions and other exclusionary policies has been partially attributed to the rise of zero-tolerance, as suspensions have become a favored method of punishing students that are also broadly applied to various infractions.[95] Even though suspensions are a commonly used form of discipline, suspension rates for all student demographics—except African Americans—have declined.[95] The increase in the rate for African Americans has followed a trend that was identified in the 1970s, when Black students were estimated to be twice as likely to receive a suspension, and that has continued to increase over time.[89] Studies have also indicated that, particularly among black women, darker skin tones may raise the risk of receiving a suspension.[93] In addition to being more likely to receive a suspension, studies have shown that black students tend to also receive longer suspensions.[89] As a result of these disparities, research has signaled that students of color perceive the gap among suspension rates as the result of intentional discrimination, rather than as efforts to appropriately enforce school rules.[93]

Exclusion from the classroom has been found to be detrimental to a student's academic performance. Research has shown that engagement in the classroom is positively related to student achievement, and, given that suspensions can last for several days, this can greatly influence the risk of academic failure—particularly among groups like Black males, who are disproportionately suspended.[90] The added impact of suspensions on Black students has been noted as compounding other issues facing them, such as higher disengagement from classes, that contribute to the racial achievement gap.[92] Academic performance is further affected by the largely-unsupervised time spent outside of the classroom, which can bring students in contact with additional youth who have been suspended or expelled from schools.[95] Suspensions also stay on a student's school record, which can shape academic or personal expectations for the student when seen by future teachers or administrators.[89] Additional consequences arising from exclusionary policies include internalization of stigmas, higher risk of dropping out, and the de facto re-segregation of schools. Exclusion from school typically coincides with labels of being 'defiant' or 'difficult to deal with' that students have a high likelihood of internalizing.[97] Moreover, the services provided during suspensions or at suspension centers often fail to address this internalization or the stigmas that result upon returning to school.[96] This can be significant for a student's educational path, as research has revealed that cycles of antisocial behaviors can result from such labels and stigmas.[97] In terms of high school dropouts, suspensions have been shown to increase the likelihood of dropping out by a factor of three, in addition to also making students three times more likely to face future incarceration.[96] On a macro-level, some researchers have begun to consider the racial gap among suspension rates as effectively re-segregating schools.[92] Although the exact causes for the de facto re-segregation of schools are still being researched, racist attitudes and cultural friction have been suggested to be potential sources of this issue.[92]

Prison pipeline

.jpg.webp)

The prison pipeline, also known as the School-to-Prison Pipeline (SPP), refers to the system of student disciplinary referrals to the American juvenile justice system, rather than using disciplinary mechanisms within schools themselves.[94] As a result of this system, negative consequences during adulthood, such as incarceration, that disproportionately impact minority students have been attributed to the pipeline, which is closely related to the issue of race in the United States criminal justice system.[91] Many studies have revealed that during childhood, exposures to the justice system make students more likely to become imprisoned later in life.[94] School disciplinary policies that overly effect Black and minority students, such as zero-tolerance and exclusionary policies, increase the risk for students to come into contact with the juvenile justice system.[94] These policies disproportionately target students of color, as evidence has revealed a rise among African American males in the prison system who were expelled from schools with recently implemented zero-tolerance policies.[98] Furthermore, suspensions have been identified as making the risk of youth incarceration three times more likely for students.[96] Other factors that have fostered the development of the prison pipeline include law enforcement on school campuses, such as school resource officers, that play a role in school discipline. Law enforcement officers intervene or perform arrests to address student issues—like drug use or assault of teachers or other students—that break the law.[97] However, implicit biases against minority students have been linked to the disciplinary recommendations made by school officers, which tend to result in more severe punishments to be levied against these students.[95]

Though many different factors have gradually led to the creation of the prison pipeline, one of the clearest indicators of its development comes from state budgets, as states have generally been increasing investments in justice system infrastructure while simultaneously divesting from education.[99] School-specific factors have also contributed to the development of the prison pipeline, including the discipline gap and the criminalization of schools.[91] A significant number of studies have indicated that exclusionary discipline can create cycles of bad behaviors that result in progressively more severe consequences—often ending in involvement with the justice system.[97] This has been evidenced by disproportionate arrest rates in schools. For example, even though they constitute only 15% of students, Black students comprise 50% of arrests in schools.[96] Subsequent punishments, especially institutional confinement, can have inadvertent consequences, such as dropping out of school.[100] Moreover, the bureaucracy of correctional institutions does not correspond well with school systems, as curriculums do not always match.[100] Consequently, students who reenroll in school tend to not only lack support systems for reentry, but they must also overcome the deficit between curriculums.[100] Research has also indicated that, especially in inner cities, the various elements of the prison pipeline are ultimately counterproductive to improving or 'fixing' a student's education and disciplinary track record.[100]

Other Policies

No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB)

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) was a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA) which aimed to improve the education of "disadvantaged" students through monetary aid, known as "Title 1 money".[101] Signed in 2001 by President Bush, NCLB aimed to create a more inclusive, responsive, and fair education system by ensuring accountability, flexibility, and increased federal support for schools.[102] NCLB emphasized the educational needs of minorities, the poor, ELL and "special education" students.[101][103] Some of the criticisms NCLB has received include that its curriculum overemphasizes math and reading, restricts teaching and devalues creativity, and fixates on improving test scores instead of the educational system.[104]

NCLB uses test scores from mathematics and reading to determine whether the achievement gap has shrunk.[104] The reliance on standardized tests may not illustrate the child's holistic progress and achievement.[105] Furthermore, these tests are used to determine whether a school meets "adequate yearly progress" (AYP).[101] Penalties are administered to schools who fail to meet AYP, an approach known as "test and punish".[104] Such penalties may include the loss of Title 1 funding, the school's closure, the "restructuring of the entire system", the school's conversion into a charter school, the provision of free tutoring, and/or permitting students "to transfer to a better-performing public school in the same district".[101][103] While some of NCLB's sanctions have been shown not to work, the forced "restructuring [of] leadership" has proven beneficial to a school's improvement.[106]

Another NCLB provision was the hiring of "highly qualified" individuals.[103] This required teachers to have a Bachelor's degree and a state-specific teaching credential.[103] Some argue that such requirements overemphasize a mastery of "subject matter" while underemphasizing interpersonal skills, such as introspection.[103] Despite NCLB's goal of reaching disadvantaged students, "highly qualified" teachers often end up at wealthier schools due to better pay.[103]

Every Student Succeeds Act

On December 10, 2015, the NCLB Act came to and end and was replaced the by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), eliminating some of the controversial provisions of NCLB. Under the new law, the federal government continues to provide a broad framework for schools. However, the responsibility of holding schools accountable shifts back to the states. Each state must set flexible goals for its schools and evaluate them accordingly.

Under the new law, states must still test students once a year in certain areas such as math and reading. However, state aren't limited to using their own tests, while concomitantly encouraging them to get rid of unnecessary testing.

In 2019, Collaborative for Student Success, an educational advocacy organization that focuses on defending efforts on advancing policies that support the development of strong systems and practices to ensure that all kids are prepared to achieve their potential and professional goals[107] held an ESSA Anniversary Summit on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. At the summit, Becky Pringle, Vice President of the National Education Association (NEA), pointed out that despite "the many successes and new opportunities [ESSA brought]...some states [hadn't] had the capacity to take advantage of the innovations built into the law."[108]

Potential solutions

Early intervention

Research studies have shown that early intervention may have drastic effects on future growth and development in children, as well as improve their well-being and reduce the demand for social services over their life.[109][110] Early intervention can include a wide array of educational activities, including an increased emphasis on reading and writing, providing additional tools or resources for learning, as well as supplements to aid special education students.[111]

Perry Preschool Project

The Perry Preschool Project in Ypsilanti, Michigan reaffirmed the positive relationship between early education and future achievement. The study assigned random 3- and 4-year-old children from low-income families to attend the Perry school, which had ample resources and a high teacher to student ratio. It also heavily emphasized the development of reading and writing skills. Once graduated, students who attended the Perry school were less than 1/5 as likely to have broken the law as compared with students who did not attend the preschool. The study also discovered that those who attended the preschool program earned, on average, $5,500 more per year than those who did not attend the school, pointing to a higher return on investment for the students who attended the Perry school. This study received widespread acclaim and validated the idea that early intervention is a powerful tool in alleviating educational and income inequality in America.[112]

Abecedarian Early Intervention Project

The Abecedarian Project in North Carolina is another study that found early intervention in education produced significant gains for future attainment. The study provided a group of infants from low-income families with early childhood education programs five days a week, eight hours each day. The educational programs emphasized language, and incorporated education into game activities.[113] This program continued for 5 years. The group's future progress was then measured as they grew older, and compared to a control group that contained students in a similar socioeconomic status that did not receive early intervention. Children who received early education were more likely to attend college, graduate high school, and reported having higher salaries. They were also less likely to engage in criminal activities, and more likely to have consistent employment.[114] This study was also highly influential in supporting the positive effect of early intervention initiatives.

General effects of early intervention

There is also more evidence that points to the beneficial effects of early intervention programs. It has been found that children who attend education centers or participate in early childhood education programs on average perform better on initial math and reading assessments than children who did not participate in these initiatives. This gap continues through the early years of children's schooling and is more prominent among groups of students who come from disadvantaged backgrounds.[115] Most social studies conducted regarding intervention programs find that inequality in early education leads to inequality in future ability, achievement, and adult success.[116] Neurological studies have also found that negative psychosocial risks in early childhood affect the developing brain and a child's development. These studies concluded that reducing the effects of these negative risks and subsequent inequality requires targeted interventions to address specific risk factors, like education.[117]

Parental involvement and engagement

Parental involvement is when schools give advice to parents on what they can do to help their children while parental engagement is when schools listen to parents on how better they can teach their students; parental involvement has been shown to work well but engagement works even better.[118] Researchers have found that high-achieving African American students are more likely to have parents who tutor them at home, provide additional practice problems, and keep in touch with school personnel.[119]

There is evidence that African American parents do value education for their child, but may not be as involved in schools because they face hostility from teachers when they give their input.[120] Lack of involvement can also be due to social class and socioeconomic status: working-class African American parents tend to have less access to "human, financial, social, and cultural resources."[121] Working-class African American parents also tend to be more confrontational toward school personnel compared to the middle-class African American parents who usually have the ability to choose what school and what class their child is enrolled in.[122]

Surveys conducted on parental involvement in low-income families showed that more than 97% of the parents said they wanted to help their children at home and wanted to work with the teachers. However, they were more likely to agree with the statements "I have little to do with my children's success in school," "Working parents do not have time to be involved in school activities," and "I do not have enough training to help make school decisions."[123] A case study of Clark Elementary in the Pacific Northwest showed that teachers involved parents more after understanding the challenges that the parents faced, such as being a non-native English speaker or being unemployed.[124]

School funding

School funding and/or quality has been shown to account for as much of a 40% variance in student achievement. While school funding can be seen as a factor that perpetuates educational inequality, it also has the ability to assist in mitigating it.

The funding gap is a term often used to explain the differences in resource allocation between high-income and low-income schools.[125] Many studies have found that states are spending less money on students from low-income communities than they are on students from high-income communities (Growing Gaps figure). A 2015 study found that across the United States, school districts with high levels of poverty are likely to receive 10 percent less per student (in resources provided from the state and local government) compared to more affluent school districts. For students of color this funding gap is more pervasive; school districts where students of color are in the majority have been shown to receive 15 percent less per student compared to school districts that are mostly white.[126][127]

The funding gap has many implications for those students whose school districts are receiving less aid from the state and local government (in comparison to less impoverished districts). For students in the former districts, this funding gap has led to poorer teacher quality which has been shown to lead to low levels of educational attainment among poor and minority students.[128] The Learning Policy Institute in 2018 has concluded from a longitudinal study that "a 21.7% increase in per-pupil spending throughout all 12 school-age years was enough to eliminate the education attainment gap between children from low-income and non-poor families and to raise graduation rates for low-income children by 20 percentage points."[129]

Charter schools

A charter school is an independent learning institution most commonly serving secondary students. It receives public funding through a charter granted to a state or local agency.[130]

Charter schools have been depicted as a controversial solution to alleviate educational inequality in the United States. In an effort to combat the impacts of living in a low-income school district, charter schools have emerged as a means of reorganizing funding to better assist low-income students and their communities. This method is designed to decrease the negative effects on students' educational quality as a result of living in a low-tax-base community.

Critics of charter schools argue they de-emphasize the significance of public education and are subject to greedy enterprise exploiting the fundamental right of education for the sole purpose of profiting. While charter schools are technically considered "public schools," opponents argue that their operational differences implicitly create differences in quality and type of public education, as standards and operating procedures are individualized based on each school. Another criticism of charter schools is the possible negative effects they may have on students who are racial minorities or come from low-income backgrounds.[131] Studies have also found charter schools to be much more segregated than their public school counterparts.[132] Free-market proponents often support charter schools, arguing they are more effective than typical public schools, specifically in reference to low-income students. Other supporters of charter schools argue that they revive participation in public education, expand existing boundaries regarding teaching methods, and encourage a more community-based approach towards education.[133] However, studies have not found conclusive evidence that charter schools as a whole are more effective than traditional public schools.[134]

One common model of charter schools is called a "no excuses" school. This label has been adopted by many charter schools as a means of indicating their dedication to a rigorous and immersive educational experience. While there is no official list of features required to be a "no-excuse" charter, they have many common characteristics. Some of these attributes include high behavioral expectations, strict disciplinary codes, college preparatory curriculum, and initiatives to hire and retain quality teachers.[135]

School discipline reform

Educational and disciplinary inequalities are complex and multi-faceted, but there have been many proposals to reduce disparities. Some researchers suggest that improving relationships between students and teachers, as well as the overall school culture, can better support minority students and provide a foundation for other reforms.[136] Research has shown that when teachers are engaging and involved in a student's success, African American students are more likely to accept them.[137] Engaging teaching styles can better connect with Black students, who often face more barriers to success, and improve classroom management, reducing behavioral conflicts and the need for disciplinary intervention.[137] Suggestions for improving teaching styles include accounting for challenges students may face outside of school, contextualizing student actions, implicit bias training, and acknowledging cultural differences between teachers and students.[91][95] Even though research about how to reduce the discipline gap is still ongoing, acknowledging the risk of bias when disciplining students has been noted as a potential method of limiting the growth of the gap.[90]

Other approaches related to reducing the discipline gap focus on disciplinary practices themselves. It has been suggested that school discipline should center around empathetic accountability systems rather than punitive consequences.[96] Research has shown that negative perceptions of a school's disciplinary climate can lead to apathy towards rules and school in general.[138] One method of implementing this shift is through Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS), which focuses on building relationships and proactively discussing rules and codes of conduct with students.[95] However, critics note that it can be expensive to implement.[95] Advocates for school discipline reform have also expressed interest in applying restorative justice practices to school disciplinary procedures.[96] Restorative justice in schools uses conflict mediation to address disciplinary infractions and build stronger relationships between parties involved; however, the efficacy of restorative programs is still being determined.[138] Additional approaches focus on mitigating the negative consequences of zero-tolerance policies by expanding disciplinary options and moving away from exclusionary policies such as suspensions or expulsions.[137][90] Community involvement has also been suggested to address discrepancies in disciplinary policies by bringing families and school officials together to improve advocacy for minority students.[136] This approach has had some success, such as in California communities where community advocacy involving youth, school officials, and family members successfully addressed disciplinary issues related to suspensions.[139]

Given that the discipline gap disproportionately moves Black and minority students into the prison pipeline, school discipline reform has also focused on reducing the factors that contribute to the pipeline. Advocates note that shifting away from bias and policies that contribute to the pipeline, such as punitive discipline, also entails broader considerations of how the pipeline manifests and costs society.[96] Suspensions and other precursors to the pipeline not only potentially lead to future incarceration, but also to societal expenses that range from costs associated with crime to forfeited sources of tax revenue.[138] Other reforms related to breaking the pipeline include addressing transitional issues between correctional facilities and schools, as transitions often fail to effectively transfer students without a loss of school time.[100] Ensuring better transitions has been identified as a potential area that can be addressed by legislation and policymakers.[100] Additionally, reform efforts also include raising awareness of how juvenile justice system referrals or other disciplinary punishments can lead to severe consequences later in life for students, especially since school staff and resource officers have a degree of discretion when issuing punishments.[100]

References

- "Why Segregation Matters: Poverty and Educational Inequality — The Civil Rights Project at UCLA". www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- Dominguez, Diana Carol, "The History of Inequality in Education and the Question of Equality Versus Adequacy" (2016). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 143. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/143

- Shipton, Clifford K. (1958). "The Puritan Influence in Education". Pennsylvania History. 25 (3): 223–233. JSTOR 27769818.

- Yeboah, Alberta. "Education among Native Americans in the periods before and after contact with Europeans: An overview." In Annual National Association of Native American Studies Conference. Houston Texas. 2005.

- Marr, Carolyn. 2000. Assimilation through education: Indian boarding schools in the Pacific Northwest. [Seattle]: University of Washington Libraries. http://content.lib.washington.edu/aipnw/marr.html.

- Smith, Andrea (2004). "Boarding School Abuses, Human Rights, and Reparations". Social Justice. 4 (98): 89–102. JSTOR 29768278.

- Virginia Historical Society, "Beginnings of Black Education", Virginia Historical Society, http://www.vahistorical.org/civilrights/education.htm (accessed Oct. 20, 2020).

- Davis, Edward M. 1845. Extracts from the American slave code. Philadelphia: s.n. https://archive.org/details/extractsfromamer00davi.

- Tyack, David; Lowe, Robert (1986). "The Constitutional Moment: Reconstruction and Black Education in the South". American Journal of Education. 94 (2): 236–256. doi:10.1086/443844. JSTOR 1084950. S2CID 143849662.

- Snyder, Thomas, ed. (January 1993). 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait (PDF). U.S Department of Education.

- Orfield, Gary; Lee (January 13, 2005). "Why Segregation Matters: Poverty and Educational Inequality". The Civil Rights Project.

- Ballantyne, David T. (2018). "The American Civil Rights Movement, 1865–1950: Black Agency and People of Good Will by Russell Brooker". Journal of Southern History. 84 (3): 771–773. doi:10.1353/soh.2018.0218. S2CID 159667536.

- Mago, Robert (1990). Race and Schooling in the South, 1880–1950: An Economic History. University of Chicago Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-226-50510-7.

- "A Bold Agenda for School Integration". The Century Foundation. 2019-04-08. Retrieved 2020-09-17.

- Bigler, R.; Liben, L.S. (2006). "A Developmental Intergroup Theory of Social Stereotypes and Prejudices". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: 39–89.

- Frankenberg, Erica (2008). "Lessons In Integration". Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- "ERIC - Education Resources Information Center" (PDF). files.eric.ed.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

- Kiviat, Barbara (2000). "The Social Side of Schooling". Johns Hopkins Magazine.

- Gershenson, Seth; Holt, Stephen B.; Papageorge, Nicholas W. (2016-06-01). "Who believes in me? The effect of student–teacher demographic match on teacher expectations". Economics of Education Review. 52: 209–224. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.002. hdl:10419/114079.

- Oppong, Thomas (2018-08-02). "Pygmalion Effect: How Expectation Shape Behaviour For Better or Worse". Medium. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Harber, Kent D.; Gorman, Jamie L.; Gengaro, Frank P.; Butisingh, Samantha; Tsang, William; Ouellette, Rebecca (2012). "Students' race and teachers' social support affect the positive feedback bias in public schools". Journal of Educational Psychology. 104 (4): 1149–1161. doi:10.1037/a0028110.

- Weir, Kirsten (2016). "Inequality at school". Monitor on Psychology. 47: 42.

- Jacoby-Senghor, Drew S.; Sinclair, Stacey; Shelton, J. Nicole (2016-03-01). "A lesson in bias: The relationship between implicit racial bias and performance in pedagogical contexts". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 63: 50–55. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.010.

- Hanselman, Paul (2019-07-09). "Access to Effective Teachers and Economic and Racial Disparities in Opportunities to Learn". The Sociological Quarterly. 60 (3): 498–534. doi:10.1080/00380253.2019.1625732. PMC 7500583. PMID 32952223.

- "Teacher Quality: Understanding the Effectiveness of Teacher Attributes". Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- Woodson, Carter G. (Carter Godwin) (1933). The mis-education of the Negro. Internet Archive. Trenton, N.J. : AfricaWorld Press. ISBN 978-0-86543-171-3.

- Brown, M. Christopher, (2005). The Politics of Curricular Change : Race, Hegemony, and Power in Education. Land, Roderic R., 1975-. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 0-8204-4863-X. OCLC 1066531199.

- Stout, Mary, 1954- (2012). Native American boarding schools. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-38676-3. OCLC 745980477.

- Reclaiming the multicultural roots of U.S. curriculum : communities of color and official knowledge in education. Brown, Anthony Lamar; Aramoni Calderón, Dolores; Banks, James A. New York. ISBN 978-0-8077-5678-2. OCLC 951742385

- King, J. LaGarret (September 22, 2014). "When Lions Write History". Multicultural Education. 22: 2–.

- Swartz, Ellen (1992). "Emancipatory Narratives: Rewriting the Master Script in the School Curriculum". The Journal of Negro Education. 61 (3): 341–355. doi:10.2307/2295252. JSTOR 2295252.

- Powell, Arthur B.; Frankenstein, Marilyn, eds. (1997). Ethnomathematics: challenging eurocentrism in mathematics education. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 61–73. ISBN 0-585-07569-7. OCLC 42855885.

- Mills, Charles W. (1994). "Revisionist Ontologies: Theorizing White Supremacy". Social and Economic Studies. 43 (3): 105–134. JSTOR 27865977.

- Elson, Ruth Miller (1964). Guardians of Tradition: American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Huber, Lindsay Perez; Johnson, Robin N.; Kohli, Rita (2006). "Naming Racism: A Conceptual Look at Internalized Racism in U.S. Schools". Chicana/o-Latina/o Law Review. 26 (1): 183–206. doi:10.5070/C7261021172.

- Crawford, Leslie W. (1993). Language and literacy learning in multicultural classrooms. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-13499-8. OCLC 26396748.

- Charity Hudley, Anne H. (2011). Understanding English language variation in U.S. schools. Mallinson, Christine. New York: Teachers College Press. pp. 73–76. ISBN 978-0-8077-5148-0. OCLC 653842746.

- Allen, Van S. (1971). "An Analysis of Textbooks Relative to the Treatment of Black Americans". The Journal of Negro Education. 40 (2): 140–145. doi:10.2307/2966724. JSTOR 2966724.

- Roland Fryer (2006-06-22). "Acting White". Education Next. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- Boutte, Gloria Swindler (2008). "Beyond the Illusion of Diversity: How Early Childhood Teachers Can Promote Social Justice". The Social Studies. 99 (4): 165–173. doi:10.3200/TSSS.99.4.165-173. S2CID 144795606.

- Brown, Anthony L.; Brown, Keffrelyn D. (2010). ""A Spectacular Secret:" Understanding the Cultural Memory of Racial Violence in K-12 Official School Textbooks in the Era of Obama". Race, Gender & Class. 17 (3/4): 111–125. JSTOR 41674755.

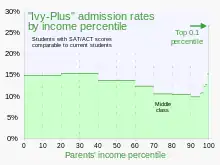

- Chetty, Raj; Deming, David J.; Friedman, John N. (July 2023). "Diversifying Society's Leaders? The Determinants and Consequences of Admission to Highly Selective Colleges" (PDF). Opportunity Insights. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2023. Figure 3. "Ivy-Plus" refers to Ivy League schools plus others with similar prestige, rankings or selectivity.

- Hart, Betty (2003). "The Early Catastrophe". American Educator.

- "The Condition of Education - Preprimary, Elementary, and Secondary Education - Family Characteristics - Family Involvement in Education-Related Activities Outside of School - Indicator July (2018)". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- Center, NSC Research (2019-10-07). "High School Benchmarks - 2019". National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- "The Condition of Education - Preprimary, Elementary, and Secondary Education - Family Characteristics - Children's Internet Access at Home - Indicator May (2020)". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- "Education and Socioeconomic Status Factsheet". www.apa.org. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

- Willingham, Daniel (2012). "Why Does Family Wealth Affect Learning?". American Educator.

- "Pa. Court sides with plaintiffs in K-12 school funding case". 7 February 2023.

- Jencks, Christopher; Mayer, Susan E. (1990). "The Social Consequences of Growing Up in a Poor Neighborhood". Inner-City Poverty in the United States. The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/1539. ISBN 978-0-309-04279-6.

- Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne (2000). "The Neighborhoods They Live in: The Effects of Neighborhood Residence on Child and Adolescent Outcomes". Psychological Bulletin. 126 (2): 309–337. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. PMID 10748645.

- Galster, George; Marcotte, Dave E.; Mandell, Marv; Wolman, Hal; Augustine, Nancy (2007-09-01). "The Influence of Neighborhood Poverty During Childhood on Fertility, Education, and Earnings Outcomes". Housing Studies. 22 (5): 723–751. doi:10.1080/02673030701474669. S2CID 37204386.

- Smedley, Brian D.; Stith, Adrienne Y.; Colburn, Lois; Evans, Clyde H.; Medicine (US), Institute of (2001). Inequality in Teaching and Schooling: How Opportunity Is Rationed to Students of Color in America. National Academies Press.

- "Common Core of Data: Public Elementary and Secondary School Revenues and Current Expenditures, 1982-1988". Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 1998-07-28. doi:10.3886/icpsr06943.

- Davis, Jessica, and Kurt Bauman. "School Enrollment in the United States: 2011. Population Characteristics. P20-571." US Census Bureau (2013).

- "Back to school statistics". National Center for Education Statistics. IES. Retrieved Oct 21, 2020.

- "Average Private School Tuition Cost". Private School Review. Retrieved Oct 21, 2020.