Economic effects of the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks in 2001 were followed by initial shocks causing global stock markets to drop sharply. The attacks themselves resulted in approximately $40 billion in insurance losses, making it one of the largest insured events ever.[1]

Financial markets

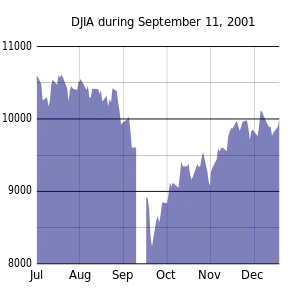

On Tuesday, September 11, 2001, the opening of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was delayed after the first plane crashed into the World Trade Center's North Tower, and trading for the day was canceled after the second plane crashed into the South Tower. NASDAQ also canceled trading. The New York Stock Exchange Building was then evacuated as well as nearly all banks and financial institutions on Wall Street and in many cities across the country. The London Stock Exchange and other stock exchanges around the world were also closed down and evacuated in fear of follow-up terrorist attacks. The New York Stock Exchange remained closed until the following Monday. This was the third time in history that the NYSE experienced prolonged closure, the first time being in the early months of World War I[2][3] and the second being March 1933 during the Great Depression. Trading on the United States bond market also ceased; the leading government bond trader, Cantor Fitzgerald, was based in the World Trade Center.[4] The New York Mercantile Exchange was also closed for a week after the attacks.[5]

The Federal Reserve issued a statement, saying it was "open and operating. The discount window is available to meet liquidity needs."[6] The Federal Reserve added $100 billion in liquidity per day, during the three days following the attack to help avert a financial crisis.[5] Federal Reserve Governor Roger W. Ferguson Jr. has described in detail this and the other actions that the Fed undertook to maintain a stable economy and offset potential disruptions arising in the financial system.[7]

Gold prices spiked upwards, from $215.50 to $287 an ounce in London trading.[4] Oil prices also spiked upwards.[8] Gas prices in the United States also briefly shot up, though the spike in prices lasted only about one week.[5]

Currency trading continued, with the United States dollar falling sharply against the Euro, British pound, and Japanese yen.[4] The next day, European stock markets fell sharply, including declines of 4.6% in Spain, 8.5% in Germany,[4] and 5.7% on the London Stock Exchange.[9] Stocks in the Latin American markets also plunged, with a 9.2% drop in Brazil, 5.2% drop in Argentina, and 5.6% decline in Mexico, before trading was halted.[4]

Economic sectors

In international and domestic markets, stocks of companies in some sectors were hit particularly hard. Travel and entertainment stocks fell, while communications, pharmaceutical and military/defense stocks rose. Online travel agencies particularly suffered, as they cater to leisure travel.

Insurance

Insurance losses due to 9/11 were more than one and a half times greater than what was previously the largest disaster (Hurricane Andrew) in terms of losses. The losses included business interruption ($11.0 billion), property ($9.6 billion), liability ($7.5 billion), workers compensation ($1.8 billion), and others ($2.5 billion). The firms with the largest losses included Berkshire Hathaway, Lloyd's, Swiss Re, and Munich Re, all of which are reinsurers, with more than $2 billion in losses for each.[10] Shares of major reinsurers, including Swiss Re and Baloise Insurance Group dropped by more than 10%, while shares of Swiss Life dropped 7.8%.[11] Although the insurance industry held reserves that covered the 9/11 attacks, insurance companies were reluctant to continue providing coverage for future terrorist attacks. Only a few insurers continue to offer such coverage.

Airlines and aviation

Flights were grounded in various places across the United States and Canada that did not necessarily have operational support in place, such as dedicated ground crews. A large number of transatlantic flights landed in Gander, Newfoundland and in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with the logistics handled by Transport Canada in Operation Yellow Ribbon. To help with the immediate needs of victims' families, United Airlines and American Airlines both provided initial payments of $25,000.[12] The airlines were also required to refund ticket purchases for anyone unable to fly.[12]

The 9/11 attacks compounded financial troubles that the airline industry already was experiencing before the attacks. Share prices of airlines and airplane manufacturers plummeted after the attacks. Midway Airlines, already on the brink of bankruptcy, shut down operations almost immediately afterward. Swissair, unable to make payments to creditors on its large debt was grounded on 2 October 2001 and later liquidated.[13] Other airlines were threatened with bankruptcy, and tens of thousands of layoffs were announced in the week following the attacks. To help the industry, the federal government provided an aid package to the industry, including $10 billion in loan guarantees, along with $5 billion for short-term assistance.[1]

The reduction in air travel demand caused by the attack is also seen as a contributory reason for the retirement of the only supersonic aircraft in service at the time, Concorde.[14]

Tourism

Tourism in New York City plummeted, causing massive losses in a sector that employed 280,000 people and generated $25 billion per year. In the week following the attack, hotel occupancy fell below 40%, and 3,000 employees were laid off. Tourism, hotel occupancy, and air travel also fell drastically across the nation. The reluctance to fly may have been due to increased fear of a repeat attack. Suzanne Thompson, Professor of Psychology at Pomona College, conducted interviews of 501 people who were not direct victims of 9/11. From this, she concluded that "Most participants felt more distress (65 percent) and a stronger fear of flying (55 percent) immediately after the event than they did before the attacks."[15]

Security

Since the 9/11 attacks, substantial resources have been put towards improving security, in the areas of homeland security, national defense, and in the private sector.[5][16]

New York City

In New York City, approximately 430,000 jobs were lost and there were $2.8 billion in lost wages over the three months following the 9/11 attacks. The economic effects were mainly focused on the city's export economy sectors.[17] The GDP for New York City was estimated to have declined by $30.3 billion over the last three months of 2001 and all of 2002. The Federal government provided $11.2 billion in immediate assistance to the Government of New York City in September 2001, and $10.5 billion in early 2002 for economic development and infrastructure needs.[18]

The 9/11 attacks also had great impact on small businesses in Lower Manhattan, located near the World Trade Center. Approximately 18,000 small businesses were destroyed or displaced after the attacks. The Small Business Administration provided loans as assistance, while Community Development Block Grants and Economic Injury Disaster Loans were used by the Federal Government to provide assistance to small business affected by the 9/11 attacks.[18]

Other effects

The September 11 attacks also led directly to the U.S. war in Afghanistan, as well as additional homeland security spending. The attacks were also cited as a rationale for the Iraq war. The cost of the two wars so far has surpassed $6 trillion.[19][20]

References

- Makinen, Gail (September 27, 2002). "The Economic Effects of 9/11: A Retrospective Assessment" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. CRS–4.

- forbes.com What can close the NYSE? 2012/10/29

- "Global financial data".

- Norris, Floyd, Jonathan Fuerbringer (September 12, 2001). "Stock". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Makinen, Gail (September 27, 2002). "The Economic Effects of 9/11: A Retrospective Assessment" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. CRS–2.

- "Federal Reserve Release". Federal Reserve. September 11, 2001.

- "FRB: Speech, Ferguson--September 11--February 5, 2003". www.federalreserve.gov.

- Stevenson, Richard W., Stephen Labaton (September 12, 2001). "The Financial World Is Left Reeling by Attack". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Shares suffer biggest fall since September 11, 2001".

- Hubbard, R Glenn; Bruce Deal; Peter Hess (2005). "The Economic Effects Of Federal Participation In Terrorism Risk". Risk Management & Insurance Review. 8 (2): 177. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6296.2005.00056.x. S2CID 153659172.

- Sorkin, Trimi Slade, Simon Romero (September 12, 2001). "Reinsurance Companies Wait to Sort Out Cost of Damages". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zuckerman, Laurence (September 12, 2001). "For the First Time, the Nation's Entire Airspace Is Shut Down". The New York Times.

- "CNN.com - Swissair jets grounded as cash runs out - Oct. 2, 2001". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- "Concorde and supersonic travel". The Independent. October 19, 2013.

- "Study on Effects of 9/11 Attacks Show Most Americans Feel More Vulnerable | College News". September 27, 2013. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013.

- Aggarwal, Vikas A.; Wu, Brian (2015). "Organizational Constraints to Adaptation: Intrafirm Asymmetry in the Locus of Coordination". Organization Science. 26: 218–238. doi:10.1287/orsc.2014.0929.

- Dolfman, Michael L., Solidelle F. Wasser (2004). "9/11 and the New York City Economy". Monthly Labor Review. 127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Makinen, Gail (September 27, 2002). "The Economic Effects of 9/11: A Retrospective Assessment" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. CRS–5.

- Khimm, Suzy (May 3, 2011). "Osama bin Laden didn't win, but he was 'enormously successful'". The Washington Post.

- Heath, Thomas (May 3, 2011). "Bin Laden's war against the U.S. economy". The Washington Post.

External links

- Attack Gave a Devastating Shove to the City's Teetering Economy, The New York Times, September 8, 2002

- As Companies Scatter, Doubts on Return of Financial District, The New York Times, September 16, 2002