Early life of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Russian: Влади́мир Ильи́ч Улья́нов) was born on 22 April 1870 (O.S. 10 April). He was better known by his alias Lenin. He became a revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1922 and of the Soviet Union from 1922 to his death in 1924.

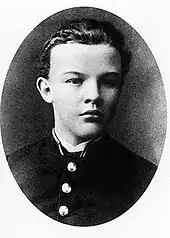

Vladimir Lenin | |

|---|---|

Lenin circa 1887 | |

| Born | 22 April 1870 |

| Died | 21 January 1924 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation(s) | Communist revolutionary; politician; socio-political theorist |

Childhood: 1870–1887

Lenin's father, Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov, was the fourth child of impoverished tailor Nikolai Vassilievich Ulyanov (born a serf father); and a far younger woman named Anna Alexeevna Smirnova, who lived in Astrakhan. Ilya escaped poverty by studying physics and mathematics at the Kazan State University, before teaching at the Penza Institute for the Nobility from 1854.[1] Introduced to Maria Alexandrovna Blank, they married in the summer of 1863.[2] From a relatively prosperous background, Maria was the daughter of a Russian Jewish physician, Alexander Dmitrievich Blank, and his German-Swedish wife, Anna Ivanovna Grosschopf, who was the daughter of a wealthy Lutheran family from Germany.[3] Alexander Blank was a Protestant convert[4] who was the son of Moishe Blank, a Jewish merchant from Volhynia, and his wife Miriam Froimovich.[5] Dr. Blank had insisted on providing his children with a good education, ensuring that Maria learned Russian, German, English and French, and that she was well versed in Russian literature.[6] Soon after their wedding, Ilya obtained a job in Nizhni Novgorod, rising to become Inspector of Primary Schools in the Simbirsk district six years later. Five years after that, he was promoted to Director of Public Schools for the province, overseeing the foundation of over 450 schools as a part of the government's plans for modernisation. Awarded the Order of St. Vladimir, he became a hereditary nobleman. With it he gained the right to be addressed as "Your Excellency".[7][3] Lenin's Jewish ancestry was concealed by the Soviet authorities, despite an appeal in the form of a letter from his sister Anna to Josef Stalin in 1932, where she remarked that this fact could be used to combat antisemitism; Stalin's reaction was that not one word was to be told of this letter.[3]

The couple, now nobility, had two children, Anna (born 1864) and Alexander (born 1866) before the birth of their third child, Vladimir "Volodya" Ilyich (Russian: Владимир Ильич Ульянов), on 22 April 1870, baptised in St. Nicholas Cathedral several days later. They would be followed by three more children, Olga (born 1871), Dmitry (born 1874) and Maria (born 1878). Another brother, Nikolai, had died several days after birth in 1873.[8] Ilya was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church and baptised his children into it, although Maria – a Lutheran – was largely indifferent to Christianity, a view that influenced her children.[9] Lenin's mother ran the household in a Protestant manner[10][11] Both parents were monarchists and liberal conservatives, being committed to the Emancipation reform of 1861 introduced by the reformist Tsar Alexander II; they avoided political radicals and there is no evidence that the police ever put them under surveillance for subversive thought.[12] The claim that Ilya exerted a revolutionary influence on his children is considered a myth. According to Lenin's sister Anna, he was a "religious man", a great admirer of the reforms of Tsar Alexander II of the 1860s, and "that he saw it as his job to protect the youth from radicalism."[3]

Every summer they left their home in Moscow Street, Simbirsk and holidayed at a rural manor in Kokushkino, shared with Maria's Veretennikov cousins.[13] Among his siblings, Vladimir was closest to his sister Olya, whom he bossed around, having an extremely competitive nature; he could be destructive, but usually admitted misbehaviour.[14] A keen sportsman, he spent much of his free time outdoors or playing chess, but his father insisted that he devote his life to study, leading him to excel at school, the Simbirsk Classical Gimnazia, a disciplinarian and conservative institution. By his teenage years, Vladimir was coaching his elder sister in Latin and gave private tuition to a Chuvash student.[15] Vladimir was also fond of the Blank estate, a place he spent a lot of time at in his youth; in his youth he was proud to describe himself as the son of a squire; and he once signed himself as "Hereditary Nobleman Vladimir Ulyanov" before the police. This noble background was noticed by many, among them the writer Maxim Gorky, and is said to have greatly influenced his personality.[3]

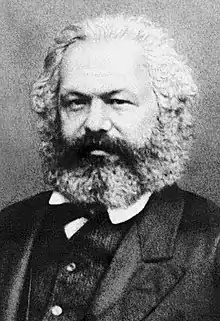

Ilya Ulyanov died of a brain haemorrhage on 12 January 1886, when Vladimir was 15 years old.[16] Vladimir's behaviour became erratic and confrontational, and shortly thereafter he renounced his belief in God.[17] At the time, Vladimir's elder brother Aleksandr "Sacha" Ulyanov was studying biology at Saint Petersburg University, in 1885 having been awarded a gold medal for his dissertation, after which he was elected onto the university's Scientific-Literary Society. Involved in political agitation against the absolute monarchy of reactionary Tsar Alexander III which governed the Russian Empire, he studied the writings of banned leftists like Dmitry Pisarev, Nikolay Dobrolyubov, Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Karl Marx. Organising protests against the government, he joined a socialist revolutionary cell bent on assassinating the Tsar and was selected to construct a bomb. Before the attack commenced, the conspirators were arrested and tried. On 25 April 1887, Sacha was sentenced to death by hanging, and executed on 8 May.[18] Despite the emotional trauma brought on by his father and brother's deaths, Vladimir continued studying, leaving school with a gold medal for his exceptional performance, and decided to study law at Kazan University.[19] Lenin's headmaster at the gymnasium was Fedor Kerensky, the father of what would later become his arch-rival in 1917, Alexander. During his last year at the gymnasium in 1887, Kerensky wrote a report on Vladimir, describing him as a "model student, never 'giving cause for dissatisfaction, by word or by deed, to the school authorities'". Kerensky put this down to his moral upbringing, writing that "religion and discipline were the basis of his upbringing, the fruits of which are apparent in Ul'ianov's behavior". At this point there were many indications that he would create an established career in the Tsarist bureaucracy, following in the footsteps of his father.[3]

University and political radicalism: 1887–1893

Entering the Judicial Faculty of Kazan University in August 1887, Vladimir and his mother moved into a flat, renting out their Simbirsk family home.[20] Becoming interested in his late brother's radical ideas, he began meeting with a revolutionary cell run by the militant agrarian socialist Lazar Bogoraz, associating with leftists intent on reviving the People's Freedom Party (Narodnaya Volya). Joining the university's illegal Samara-Simbirsk zemlyachestvo, he was elected as its representative for the university's zemlyachestvo council.[21] On 4 December he took part in a demonstration demanding the abolition of the 1884 statute and the re-legalisation of student societies, but along with 100 other protesters was arrested by police. Accused of being a ringleader, the university expelled him and the Ministry of Internal Affairs placed him under police surveillance, exiling him to his Kokushkino estate.[22] Here, he read voraciously, becoming enamoured with Chernyshevsky's novel What is to be Done? (1863).[23] Disliking his radicalism, in September 1888 his mother persuading him to write to the Ministry of the Interior asking them to allow him to study at a foreign university; they refused his request, but allowed his return to Kazan, where he settled on the Pervaya Gora with his mother and brother Dmitry.[24]

In Kazan, he contacted M.P. Chetvergova, joining her secret revolutionary circle, through which he discovered Karl Marx's Capital (1867); exerting a strong influence on him, he became increasingly interested in Marxism.[25] Wary of his political views, his mother purchased an estate in the village of Alakaevka, Samara Oblast – made famous in the work of poet Gleb Uspensky, of whom Lenin was a great fan – in the hope that Vladimir would turn his attention to agriculture. Here, he studied peasant life and the poverty they faced, but remained unpopular as locals stole his farm equipment and livestock, causing his mother to sell the farm.[26]

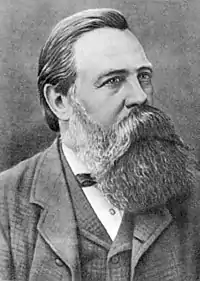

In September 1889, the Ulyanovs moved to Samara for the winter. Here, Vladimir contacted exiled dissidents and joined Alexei Sklyarenko's discussion circle. Both Vladimir and Sklyarenko adopted Marxism, with Vladimir translating Marx and Friedrich Engels' political pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto (1848), into Russian. He began to read the works of the Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, a founder of the Black Repartition movement, concurring with Plekhanov's argument that Russia was moving from feudalism to capitalism. Becoming increasingly sceptical of the effectiveness of militant attacks and assassinations, he argued against such tactics in a December 1889 debate with M.V. Sabunaev, an advocate of the People's Freedom Party. Despite disagreeing on tactics, he made friends among the Party, in particular with Apollon Shukht, who asked Vladimir to be his daughter's godfather in 1893.[27]

In May 1890, Mariya convinced the authorities to allow Vladimir to undertake his exams externally at a university of his choice. Choosing the University of Saint Petersburg and obtaining the equivalent of a first-class degree with honours, celebrations were marred when his sister Olga died of typhoid.[28] In 1891, during the famine, he sued the peasant neighbours of his family's estate for causing damage to it; he also drew most of his income from rents and interest derived from the sale of the estate of his mother, despite later condemning "gentry capitalism".[3] Vladimir remained in Samara for several years, in January 1892 being employed as a legal assistant for a regional court, before gaining a job with a local lawyer. Embroiled primarily in disputes between peasants and artisans, he devoted much time to radical politics, remaining active in Sklyarenko's group and formulating ideas about Marxism's applicability to Russia. Inspired by Plekhanov's work, Vladimir collected data on Russian society, using it to support a Marxist interpretation of societal development and increasingly rejecting the claims of the People's Freedom Party.[29] In the spring of 1893, Lenin wrote a paper, "New Economic Developments in Peasant Life"; submitted to the liberal journal Russian Thought, it was rejected and only published in 1927.[30] In the autumn of 1893, Lenin wrote another article, "On the So-Called Market Question", a critique of Russian economist German Krasin (1871-1947).[31][32]

References

Footnotes

- Fischer 1964, pp. 1–2; Rice 1990, pp. 12–13; Service 2000, pp. 21–23.

- Fischer 1964, p. 5; Rice 1990, p. 13; Service 2000, p. 23.

- Figes, pp. 142–143

- Possony, Stefan T. (8 May 2019). Lenin: The Compulsive Revolutionary. ISBN 9781138637894.

- Petrovsky-Shtern 2010, p. 28

- Fischer 1964, pp. 2–3; Rice 1990, p. 12; Service 2000, pp. 16–19, 23.

- Fischer 1964, p. 6; Rice 1990, pp. 13–14, 18; Service 2000, pp. 25, 27.

- Fischer 1964, p. 6; Rice 1990, pp. 12, 14; Service 2000, pp. 13, 25.

- Fischer 1964, pp. 3, 8; Rice 1990, pp. 14–15; Service 2000, p. 29.

- Conquest 1972, p. 14

- Borowski, Birgit (1994). Baedeker's St. Petersburg. New York, N.Y.: Prentice Hall. pp. 18–19. OCLC 1028674170. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Fischer 1964, p. 8; Service 2000, p. 27.

- Rice 1990, p. 18; Service 2000, p. 26.

- Fischer 1964, p. 7; Rice 1990, p. 16; Service 2000, pp. 32–36.

- Fischer 1964, p. 7; Rice 1990, p. 17; Service 2000, pp. 36–46.

- Fischer 1964, pp. 6, 9; Rice 1990, p. 19; Service 2000, pp. 48–49.

- Fischer 1964, p. 9; Service 2000, pp. 50–51, 64.

- Fischer 1964, pp. 10–17; Rice 1990, pp. 20, 22–24; Service 2000, pp. 52–58.

- Fischer 1964, p. 18; Rice 1990, p. 25; Service 2000, p. 61.

- Fischer 1964, p. 18; Rice 1990, p. 26; Service 2000, pp. 61–63.

- Rice 1990, pp. 26–27; Service 2000, pp. 64–68, 70.

- Fischer 1964, p. 18; Rice 1990, p. 27; Service 2000, pp. 68–69.

- Fischer 1964, p. 18; Rice 1990, p. 28.

- Fischer 1964, p. 18; Rice 1990, p. 31; Service 2000, p. 71.

- Fischer 1964, p. 19; Rice 1990, pp. 32–33; Service 2000, p. 72.

- Fischer 1964, p. 19; Rice 1990, p. 33; Service 2000, pp. 74–76.

- Rice 1990, p. 34; Service 2000, pp. 77–80.

- Rice 1990, pp. 34–36; Service 2000, pp. 82–86.

- Fischer 1964, p. 21; Rice 1990, pp. 36–37; Service 2000, pp. 86–90.

- Fischer 1964, p. 21; Rice 1990, p. 38; Service 2000, pp. 93–94. Published as V. I. Lenin, "New Economic Developments in Peasant Life" contained in the Collected Works of V. I. Lenin: Volume 1 (Progress Publishers: Moscow, 1972) pp. 11-73.

- V. I. Lenin, "On the So-Called Market Question" contained in the Collected Works of V. I. Lenin: Volume 1, pp. 75-125.

- "Красин Герман Борисович (1871 - 1947)".

Bibliography

- Conquest, Robert (1972). Lenin. London: Fontana/Collins. ISBN 9780006326168. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Fischer, Louis (1964). The Life of Lenin. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-1842122303.

- Read, Christopher (2005). Lenin: A Revolutionary Life. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20649-5.

- Rice, Christopher (1990). Lenin: Portrait of a Professional Revolutionary. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0304318148.

- Service, Robert (2000). Lenin: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780333726259.

- Figes, Orlando (2014). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 9781847922915.

- Petrovsky-Shtern, Yohanan (2010). Lenin's Jewish Question. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300152104.