Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour (DNT, DNET) is a type of brain tumor. Most commonly found in the temporal lobe, DNTs have been classified as benign tumours.[1] These are glioneuronal tumours comprising both glial and neuron cells and often have ties to focal cortical dysplasia.[2]

| Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour | |

|---|---|

| |

| DNET | |

| Specialty | Neuro-oncology, Neurosurgery |

Varying subclasses of DNTs have been presently identified, with dispute existing in the field on how to properly group these classes.[3] The identification of possible genetic markers to these tumours is currently underway.[4] With DNTs often causing epileptic seizures, surgical removal is a common treatment, providing high rates of success.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Seizures and epilepsy are the strongest ties to dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours.[4] The most common symptom of DNTs are complex partial seizures.[2] Simple DNTs more frequently manifest generalized seizures.[2] In children, DNTs are considered to be the second leading cause of epilepsy.[3] A headache is another common symptom.[2] Diplopia may also be a result of a DNT. Other neurological impairments besides seizures are not common.[2]

Pathogenesis

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours are largely glioneuronal tumours, meaning they are composed of both glial cells and neurons.[2]

Three subunits of DNTs have been commonly identified:[2]

- Simple: Specific glioneuronal elements are the sole components of simple DNTs.[2]

- Complex: Glial nodules and/or type 3b focal cortical dysplasia (FCD), in addition to the glioneuronal elements are present in complex DNTs.[4] Both the nodules and FCD can be present within the same tumour, though only 47% of complex DNTs are linked to FCD.[2]

- Nonspecific: Nonspecific DNTs are lacking the glioneuronal elements common to DNTs but will show glial nodules and/or type 3b FCD.[2] Eighty-five percent of nonspecific case of DNTs show this FCD.[2]

There currently exists some debate over where to make the proper division for the subunits of DNTs. A fourth subunit is sometimes noted as a mixed subunit. This mixed subunit expresses the glial nodules and components of ganglioglioma.[1] Other findings suggest that DNTs require a reclassification to associate them with oligodendrogliomas, tumours that arise from solely glial cells.[3] These reports suggest that the neurons found within DNTs are much rarer than previously reported. For the neurons that are seen in the tumours, it is suggested that they had been trapped within the tumor upon formation, and are not a part of the tumour itself.[3]

Diagnosis

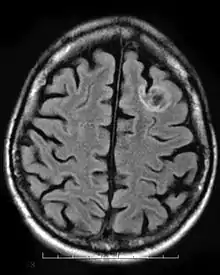

A dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumour is commonly diagnosed in patients who are experiencing seizures with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalogram (EEG).[4] A DNT is most commonly diagnosed in children who are experiencing seizures, and when given medication do not respond to them. When an MRI is taken there are lesions located in the temporal parietal region of the brain.[4]

Typical DNTs can be detected in an EEG scan when there are rapid repetitive spikes against a contrasted background.[4] EEG are predominantly localized with DNT location in the brain, however there are nonspecific cases in which the location of the tumour is abnormal and not localized.[4]

Classification

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours are classified as a benign tumour, Grade I of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of brain tumours.[1] This classification by WHO only covers the simple and complex subunits. Groups lacking glioneuronal elements were not considered to have fallen in the same group and have thusly not yet been classified.[1]

Complications in diagnosis

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours are often described as a low grade tumour because about 1.2% people under the age of twenty are affected and about 0.2% over the age of twenty are affected by this tumour.[5] Since its prevalence is small among the population, it often goes misdiagnosed or even at times goes undiagnosed.

Treatment

The most common course of treatment of DNT is surgery. About 70-90% of surgery are successful in removing the tumour.[4] Since the tumour is most often benign, and does not impose immediate threat, aggressive treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation are not needed, and therefore patients especially children and young adults do not have to go through the side effects of these treatments.[5]

In order for the seizures to completely be stopped the tumour needs to be completely removed. For the tumor to be completely removed doctors need to perform resections consisting an anterior temporal lobectomy or amygdalo-hippocampectomy.[4] Alternatively, if the tumor is found at or near the surface of the brain, it can be removed without any other requirements. It has been found that if the tumour is removed by performing resections patients are then recognized as seizure free. On the other hand, if resections are not performed, and the tumour is not completely removed, then the patient is still at risk of experiencing the seizures.[4] In a study done by Bilginer et al., 2009, looking at patients whose tumour was not completely removed, and saw that they were still experiencing seizures, concluding that the incomplete resection as a being a failure.[4] This then causes the patient to undergo a second surgery and remove the tumour in which case causing a complete resection.

Outcomes

Recurrence of the tumour is highly unlikely if the patient undergoes a complete resection since the tumour is completely taken out.[5] Most of the tumours observed in patients are benign tumours, and once taken out do not cause neurological deficits. However, there have been incidents where the tumour was malignant.[5] There have been cases where the malignant tumour has made a reoccurrence, and this happens at the site of the residual tumour in which an incomplete resection has been done.[4] In this case, a second operation has to be done in order to completely remove the malignant tumour. In a study done with Daumas Duport and Varlet, 2003, they have found that there has been one case so far that the tumour has come back, however, in that particular case the patient underwent an incomplete resection, which led them to perform a second surgery in order to remove it completely.[4] This evidence shows that surgery and complete resections are one of the better approaches in treating dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours.

Furthermore, a longer period of epilepsy, and patients older in age are less likely to have a full recovery and remain seizure free. This is the case because their body is not able to recover as quickly, as it would for a child who has had one seizure before.[5] Therefore, it is crucial to diagnose and perform the surgery early in order to make a full recovery.

Epidemiology

Children are much more prone to exhibit these dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours than adults.[1] The mean age of onset of seizures for children with DNTs is 8.1 years old.[1] Few other neurological deficits are associated with DNTs, so that earlier detection of the tumour before seizure symptoms are rare.[2] DNTs are found in the temporal lobe in 84% of reported cases.[1] In children, DNTs account for 0.6% of diagnosed central nervous system tumours.[2] It has been found that males have a slightly higher risk of having these tumours.[2] Some familial accounts of DNTs have been documented, though the genetic ties have not yet been fully confirmed.[2]

History

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumours were usually found during investigation of patients who underwent multiple seizures.[2] The tumours were encountered when the patient required surgery to help with the epilepsy to help with the seizures. The term DNT was first introduced in 1988 by Daumas-Duport, terming it dysembryoplastic, suggesting a dysembryoplastic origin in early onset seizures, and neuroepithelial to allow the wide range of possible varieties of tumours to be put into the category.[2] In 2003 and 2007, DNT was made into further subsets of categories based upon the displayed elements within the tumour.[2]

References

- Thom M, Toma A, An S, Martinian L, Hadjivassiliou G, Ratilal B, et al. (October 2011). "One hundred and one dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors: an adult epilepsy series with immunohistochemical, molecular genetic, and clinical correlations and a review of the literature". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 70 (10): 859–878. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182302475. PMID 21937911.

- Suh YL (November 2015). "Dysembryoplastic Neuroepithelial Tumors". Journal of Pathology and Translational Medicine. 49 (6): 438–449. doi:10.4132/jptm.2015.10.05. PMC 4696533. PMID 26493957.

- Komori T, Arai N (August 2013). "Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor, a pure glial tumor? Immunohistochemical and morphometric studies". Neuropathology. 33 (4): 459–468. doi:10.1111/neup.12033. PMID 23530928.

- Chassoux F, Daumas-Duport C (December 2013). "Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors: where are we now?". Epilepsia. 54 (Suppl 9): 129–134. doi:10.1111/epi.12457. PMID 24328886.

- Guduru H, Shen JK, Lokannavar HS (2012-01-01). "A rare case of dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor". Journal of Clinical Imaging Science. 2 (1): 60. doi:10.4103/2156-7514.102057. PMC 3515966. PMID 23230542.