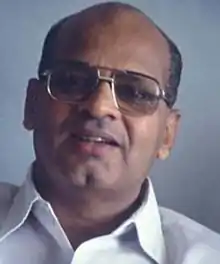

Dutta Samant

Dattatray Samant (21 November 1932 – 16 January 1997), also known as Datta Samant, and popularly referred to as Doctorsaheb, was an Indian politician and trade union leader, who is most famous for leading 200–300 thousand textile mill workers in the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) on a year-long strike in 1982, which triggered the closure of most of the textile mills in the city.[1]https://ivark.github.io

Dr Datta Samant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

| In office 1984–1989 | |

| Preceded by | R. R. Bhole |

| Succeeded by | Vamanrao Mahadik |

| Constituency | Mumbai South Central |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 November 1932 Devbag, Sindhudurg district, Maharashtra |

| Died | 16 January 1997 (aged 64) Mumbai |

| Political party | Independent |

| Children | 5 |

| Source: | |

Trade union and political career

Samant grew up in Deobag on the Konkan coast of Maharashtra, hailing from a middle-class Marathi background. He was a qualified M.B.B.S. doctor from G.S. Seth Medical College and K.E.M. hospital, Mumbai and practised as a general physician in Pantnagar locality of Ghatkhopar. The struggle of his patients, most of whom were industry labourers inspired him to fight for their cause. He spent much of his early years in the locality of Ghatkopar in Mumbai, in the state of Maharashtra. From the early 20th century, the city's economy was characterised by major textile mills, the base of India's thriving textile and garments industry. Hundreds of thousands of people from all over India were employed in working in the mills. Although a trained medical doctor, Samant was active in trade union activities amongst mill workers. He joined the Indian National Congress and its affiliated Indian National Trade Union Congress. Gaining popularity amongst city workers, Samant name was popularly known as Doctorsaheb.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Mumbai-Thane industrial belt witnessed successive working class strikes and protests, with multiple trade unions competing for the allegiance of workers and political control. These primarily included George Fernandes, the Centre for Indian Trade Unions. Samant rose to become one of the most prominent INTUC leaders, and grew increasingly militant in his political convictions and activism. Samant enjoyed success in organising strikes and winning substantial wage hikes from companies. In 1972 elections, he was elected to the Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha, or legislative assembly on a Congress ticket, and served as a legislator.[2] Samant was arrested in 1975 during the Indian Emergency owing to his reputation as a militant unionist, despite belonging to the Congress party of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Samant's popularity increased with his release in 1977 and the failure of the Janata Party coalition, with which many rival unions had been affiliated. This increased his popularity and widespread reputation for putting workers and their interests before politics.

1982 strike

In late 1981, Samant was chosen by a large group of Mumbai mill workers to lead them in a precarious conflict between the Bombay Millowners Association and the unions, thus rejecting the INTUC-affiliated Rashtriya Mill Mazdoor Sangh which had represented the mill workers for decades. Samant was requested by mill workers to lead. He suggested that they wait for outcome of initial strike action. But workers were too agitated and wanted a massive strike. At the beginning of which an estimated 200,000–300,000 mill workers walked out, forcing the entire industry of the city to be shut down for over a year. Samant demanded that along with wage hikes, the government should scrap the Bombay Industrial Act, 1947 and de-recognize the RMMS as the only official union of the city industry. While fighting for greater pay and better conditions for workers, Samant and his allies also sought to capitalise and establish their power on the trade union scene in Mumbai.

Although Samant had links with the Congress, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi considered him a serious political threat. Samant's control of the mill workers made Gandhi and other Congress leaders fear that his influence would spread to the port and dock workers and make him the most powerful union leader in India's commercial capital. Thus the government took a firm stance of rejecting Samant's demands, and refusing to budge despite the severe economic losses suffered by the city and the industry.

As the strike progressed through the months, Samant's militancy in the face of government obstinacy led to the failure of any attempts at negotiation and resolution. Disunity, mainly due to Shiv-sena trying to break strike and dissatisfaction over the strike soon became apparent, and many textile millowners began moving their plants outside the city. After a prolonged and destabilising confrontation, the strike collapsed with Samant and his allies not having obtained any concessions. The closure of textile mills across the city left tens of thousands of mill workers unemployed, and in the succeeding years the most of the industry moved away from Mumbai, after decades of rising costs and union militancy. Mill owners used this opportunity to grab the precious real estate. Although Samant remained popular with a large block of union activists, his clout and control over Mumbai trade unions disappeared.

Later life and assassination

Samant was elected on an independent, anti-Congress ticket to the 8th Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament in 1984; an election that was otherwise swept by the Congress under Rajiv Gandhi. He would organise the Kamgar Aghadi union, and the Lal Nishan Party, which brought him close to communism and Indian communist political parties. He remained active in trade unions and communist politics throughout India in 1990s. At the time of his death he was not a member of parliament.

At 11:10 a.m. (IST) on 16 January 1997, Samant was murdered outside his home in Mumbai by four gunmen, believed to be contract killers, who fled on motorcycles. As Samant left his residence in Mumbai's Powai suburb by Tata Sumo, he was obstructed by a cyclist at about 50 metres following which he had the vehicle slowed down and lowered the window assuming them to be workers. The gunmen fired 17 bullets on his head, chest and stomach using two pistols before fleeing. He was taken to the Nursing Home owned by his eldest son.[3] His death sparked protests across the city, and a large procession of union activists gathered at his cremation.[4] On 10 April 2005 police arrested 3 men and charged them for Samant's murder. On 30 October 2007, his assassin, a thug working for underworld don Chotta Rajan, was himself gunned down by police in Kolhapur .

Personal life

He was married to Dr. Vinita Samant. They had 5 children. His second son Bhushan Samant is the current President of Maharashtra General Kamgar Union.

Samant's older brother, Purushottam Samant ( Popularly known as Dada Samant) was the leader of the Maharashtra General Kamgar Union post his demise. In 2010, he filed a suit against film-maker Mahesh Manjrekar for "wrongly" portraying Datta Samant in his movie Lalbaug-Parel that the textile mills in the Mumbai closed down due to the strike he led.[5]

His niece Ruta, a former Air India airhostess, is married to Jitendra Ahwad, MLA in Maharashtra Legislative Assembly.[6]

See also

References

- "Datta Samant: A lion who prowls the embattled frontier between labour and capital". India Today. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- "STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1972 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MAHARASHTRA, Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- Someshwar, Savera R. (16 January 1997). "Datta Samant shot dead!". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 1999. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "Datta Samant Cremated". The Hindu. 18 June 1997. Archived from the original on 12 May 1997. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "Datta Samant's family slaps notice on filmmaker Mahesh Manjrekar". DNA India. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- Meet leader of pilots strike,son-in-law of unionist Datta Samant, Indian Express, May 12, 2012

- Anand, Javed (17 January 1997). "In the experience of blue-collared men, he remained the only trade union leader who put workers before politics". Rediff.com.

- "3 held for Datta Samant's murder". Rediff.com. 10 April 2005.

- Bhattacharya, Dipankar (February 1997). "Datta Samant – A Tribute". Liberation: Central Organ of CPI(ML). Archived from the original on 27 April 2006.