Dutch dialects

Dutch dialects are primarily the dialects that are both cognate with the Dutch language and spoken in the same language area as the Dutch standard language. They are remarkably diverse and are found within Europe mainly in the Netherlands and northern Belgium.

| This article is a part of a series on |

| Dutch |

|---|

| Low Saxon dialects |

| West Low Franconian dialects |

| East Low Franconian dialects |

The Dutch province of Friesland is bilingual. The West Frisian language, distinct from Dutch, is spoken here along with standard Dutch and the Stadsfries dialect. A West Frisian standard language has also been developed.

First dichotomy

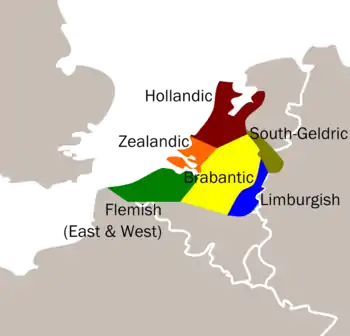

Dutch dialects can be divided into two main language groups:

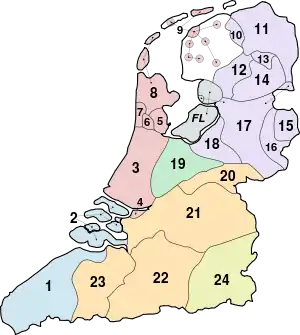

- Low Franconian (Dutch: Nederfrankisch) language area in the Souuth and West of the Netherlands (first map to the left).

- Dutch Low Saxon (Dutch: Nedersaksisch) language area in the east of the Netherlands (second map to the left): in Groningen, Drenthe, Overijssel, major parts of Gelderland, and parts of Flevoland, Friesland and Utrecht.

Classifications

In Driemaandelijkse bladen (2002) the following phonetically based division of dialects in the Netherlands is given:[1]

- Nedersaksisch

- Frisian (Fries)

- Frisian (Fries)

- West Frisian dialects (de Friese dialecten)

- Stadsfries, Kollumerlands, Bildts, Stellingwerfs (Stadfries, Kollumerlands, Bildts, Stellingwerfs)

- Veluws transitional dialects (Veluwse overgangsdialecten)

- Frisian (Fries)

- Hollandic, North Brabantian (Hollands, Noord-Brabants)

- Hollandic (Hollands)

- North Hollandic (Noord-Hollands)

- South Hollandic and Utrechts (Zuid-Hollands en Utrechts)

- North Brabantian (Noord-Brabants)

- East Brabantian (Oost-Brabants)

- dialects in the Gelders Rivierengebied, West Brabantian (dialecten in het Gelders Rivierengebied, West-Brabants),

- Hollandic (Hollands)

- North Belgian (Noord-Belgisch)

- Central Brabantian (Centraal Brabants)

- Peripheral Brabantian (Periferisch Brabants)

- Zeelandic (Zeeuws)

- Brabantian (Brabants)

- Peripheral Flemish (Periferisch Vlaams)

- Central Vlaams (Centraal Vlaams)

- Limburgish (Limburgs)

Heeringa (2004) distinguished (names as in Heeringa):[2]

- Frisian

- Frisian mixed varieties (including town Frisian (Stad(s)fries) and Stellingwerfs)

- Groningen

- Overijssel

- Southwest Limburg

- Brabant

- Central Dutch varieties

- Urk

- East Flanders

- West Flanders

- Zeeland

- Limburg

- Northeast Luik

Overview map

Jo Daan[3] and Georges De Schutter[4] categorised the Dutch dialects in the European parts of Netherlands, Belgium and France. Dutch dialects in the rest of Europe and overseas were not taken into account.

Legend

South-western dialect group

- 1. West Flemish, including French Flemish and Zeelandic Flemish

- 2. Zeelandic

North-western dialect group

- 3. South Hollandic

- 4. Westhoeks

- 5. Waterlands* and Volendams*

- 6. Zaans*

- 7. Kennemerlands

- 8. West-Frisian Dutch*

- 9. Bildts, Midslands, Stadsfries and Amelands*

* The Hollandic dialects denoted with an asterisk are highly influenced by the Westerlauwers Frisian dialect of the West Frisian language.

North-eastern dialect group

- 10. Kollumerlands

- 11. Gronings and North Drèents

- 12. Stellingwarfs

- 13. Middle Drèents

- 14. South Drèents

- 15. Tweants

- 16. Tweants-Graafschaps (both Tweants and Achterhooks)

- 17. Guelderish-Overijssels (Achterhooks, Sallands, Northwest Overijssels, and Urkers)

- 18. Veluws

Northern-central dialect group

South-central dialect group

- 20. South Guelderish

- 21. North Brabantian and North Limburgish

- 22. Brabantian

- 23. East Flemish

South-eastern dialect group

- 24. Limburgish, excluding the Kerkrade and Vaals dialect which linguistically belong to the German Ripuarian language

Miscellaneous

is the Province of Flevoland. It was established out of the former Zuiderzee by land reclaimation in the 1950s and 1960s. Due to its short existence there is no majority dialect spoken, as the inhabitants came from different parts of the Netherlands. The only exception is Urkers, by the population of the former island of Urk.

The blank area (near zone 9 and 10) speak dialects of the West Frisian language.

Minority languages

Germanic languages that have the status of official regional or minority language and are protected by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in the Netherlands are Limburgish, Dutch Low Saxon and West Frisian.[5]

Limburgish

Limburgish receives protection by chapter 2 of the charter. In Belgium, where Limburgish is spoken as well, it does not receive such recognition or protection because Belgium did not sign the charter. Limburgish has been influenced by the Ripuarian dialects like the Cologne dialect Kölsch and has had a somewhat different development since the late Middle Ages.

Dutch Low Saxon

Dutch Low Saxon also receives protection by chapter 2 of the charter. In some states of Germany, depending on the state, Low German receives protection by chapter 2 or 3.

West Frisian

West Frisian receives protection by chapter 3 of the charter. It evolved from the same West Germanic branch as Anglo-Saxon and Old Saxon and is less akin to Dutch.

Holland and the Randstad

In Holland, Hollandic is spoken, but the original forms of the dialect, which were heavily influenced by a West Frisian substratum and, from the 16th century, by Brabantian dialects, are now relatively rare. The urban dialects of the Randstad, which are Hollandic dialects, do not diverge from standard Dutch very much, but there is a clear difference between the city dialects of Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam and Utrecht.

In some rural Hollandic areas, more authentic Hollandic dialects are still being used, especially north of Amsterdam.

Another group of dialects based on Hollandic is that spoken in the cities and the larger towns of Friesland, where it partially displaced West Frisian in the 16th century and is known as Stadsfries ("Urban Frisian").

Extension across the borders

- Gronings, spoken in Groningen (Netherlands), as well as the closely related varieties in adjacent East Frisia (Germany), has been influenced by the West Frisian language and takes a special position within Dutch Low Saxon.

- South Guelderish (Zuid-Gelders) is a dialect spoken in Gelderland (Netherlands) and in adjacent parts of North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany).

- Brabantian (Brabants) is a dialect spoken in Antwerp, Flemish Brabant (Belgium) and North Brabant (Netherlands).

- West Flemish (Westvlaams) is spoken in West Flanders (Belgium), the western part of Zeelandic Flanders (Netherlands) and historically also in French Flanders (France).

- East Flemish (Oostvlaams) is spoken in East Flanders (Belgium) and the eastern part of Zeelandic Flanders (Netherlands).

- Limburgish (Limburgish: Limburgs or Lèmburgs; Dutch: Limburgs) is spoken in Limburg (Belgium) as well as in Limburg (Netherlands) and extends across the German border. It is however not a Dutch dialect but a separate related language. The mixed dialect of Dutch-Limburgish unlike Limburgish proper does not typically extend into Germany beyond Selfkant.

Recent use

Dutch dialects and regional languages are not spoken as often as they used to be. Recent research by Geert Driessen shows that the use of dialects and regional languages among both Dutch adults and youth is in heavy decline. In 1995, 27 percent of the Dutch adult population spoke a dialect or regional language on a regular basis, while in 2011 this was no more than 11 percent. In 1995, 12 percent of the primary school aged children spoke a dialect or regional language, while in 2011 this had declined to 4 percent. Of the three officially recognized regional languages Limburgish is spoken most (in 2011 among adults 54%, among children 31%) and Dutch Low Saxon least (adults 15%, children 1%); West Frisian occupies a middle position (adults 44%, children 22%).[6] In Belgium, however, dialects are very much alive; many senior citizens there are unable to speak standard Dutch.

Flanders

In Flanders, there are four main dialect groups:

- West Flemish (West-Vlaams) including French Flemish in the far North of France,

- East Flemish (Oost-Vlaams),

- Brabantian (Brabants), which includes several main dialect branches, including Antwerpian, and

- Limburgish (Limburgs).

Some of these dialects, especially West and East Flemish, have incorporated some French loanwords in everyday language. An example is fourchette in various forms (originally a French word meaning fork), instead of vork. Brussels is especially heavily influenced by French because roughly 85% of the inhabitants of Brussels speak French. The Limburgish in Belgium is closely related to Dutch Limburgish. An oddity of West Flemings (and to a lesser extent, East Flemings) is that, when they speak AN, their pronunciation of the "soft g" sound (the voiced velar fricative) is almost identical to that of the "h" sound (the voiced glottal fricative), thus, the words held (hero) and geld (money) sound nearly the same, except that the latter word has a 'y' /j/ sound embedded into the "soft g". When they speak their local dialect, however, their "g" is almost the "h" of the Algemeen Nederlands, and they do not pronounce the "h". Some Flemish dialects are so distinct that they might be considered as separate language variants, although the strong significance of language in Belgian politics would prevent the government from classifying them as such. West Flemish in particular has sometimes been considered a distinct variety. Dialect borders of these dialects do not correspond to present political boundaries, but reflect older, medieval divisions.

The Brabantian dialect group, for instance, also extends to much of the south of the Netherlands, and so does Limburgish. West Flemish is also spoken in Zeelandic Flanders (part of the Dutch province of Zeeland), and by older people in French Flanders (a small area that borders Belgium).

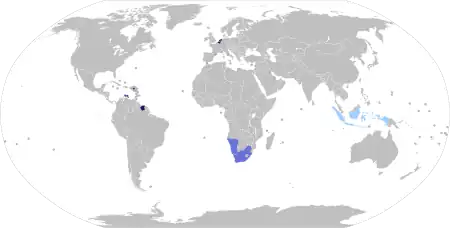

Non-European dialects, and daughter languages

Outside of Europe, there are multiple dialects and daughter languages of Dutch spoken by the population in the non-European parts of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the former Dutch colonies.

Dutch Caribbean

The Dutch Caribbean are part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The region consists of the Caribbean Netherlands (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba), three overseas special municipalities inside the country of the Netherlands, plus three constituent countries inside the Kingdom, namely Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten. Dutch is one of the official languages in all four of the constituent countries of the Kingdom,[7] however English and a Portuguese-based creole-language, called Papiamento, are the most spoken languages on the Dutch Caribbean.[8] The Dutch dialects in the Dutch Caribbean differ from island to island.

As of 2021 data the percentage of Dutch speakers in the populations of the Dutch Caribbean are:[8]

- Caribbean Netherlands: 56,8%

- Bonaire: 76,6%

- Saba: 33.0%

- Sint Eustatius: 38.3%

Suriname

Surinamese Dutch is a Dutch dialect spoken as a native language by about 80% of the population in Suriname. Dutch is one of the official languages of Suriname.[9]

Indonesia

A part of the elderly population in the former Dutch colony in Indonesia, the Dutch East Indies, still speaks a Dutch dialect.[10]

North America

Until the early 20th century, variants of Dutch were still spoken by some descendants of Dutch colonies in the United States. Nowadays, there are only a few semi-speakers of these dialects left, or the dialect went extinct already.

- New Jersey, in particular, had an active Dutch community with a highly divergent dialect spoken as recently as the 1950s. The Jersey Dutch dialect was spoken by the so called New York Dutch community.

- In Pella, Iowa, the Pella Dutch dialect is spoken.

- Mohawk Dutch is a now extinct Dutch-based creole language mainly spoken during the 17th century west of Albany, New York in the area around the Mohawk River, by the Dutch colonists who traded with or to a lesser extent mixed with the local population from the Mohawk nation.

Further reading

- Bont, Antonius Petrus de (1958) Dialekt van Kempenland 3 Deel [in ?5 vols.] Assen: van Gorcum, 1958–60. 1962, 1985

References

- Wilbert (Jan) Heeringa, Over de indeling van de Nederlandse streektalen. Een nieuwe methode getoetst, in: Driemaandelijkse bladen, jaargang 54, 2002 or Driemaandelijkse bladen voor taal en volksleven in het oosten van Nederland, vol. 54, nr. 1-4, 2002, pp. 111–148, here p. 133f. (Heeringa: Papers → cp. PDF). In this paper, Heeringa refers to: Cor & Geer Hoppenbrouwers, De indeling van de Nederlandse streektalen: Dialecten van 156 steden en dorpen geklasseerd volgens de FFM [FFM = featurefrequentie-methode, i.e. feature-frequency method], 2001

- Wilbert (Jan) Heeringa, Chapter 9: Measuring Dutch dialect distances, of the doctor's thesis: Measuring Dialect Pronunciation Differences using Levenshtein Distance, series: Groningen Dissertations in Linguistics (GRODIL) 46, 2004, (esp.) p. 231, 215 & 230 (thesis, chapter 9 (PDF), alternative source)

- Daan, Jo (1969). Van Randstad tot Landrand. Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgevers Maatschappij.

- König, Ekkehard; van der Auwera, Johan, eds. (2005) [1st published 1994]. The Germanic Languages. Routledge Language Family Descriptions (Digital print ed.). London / New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05768-4.. Georges De Schutter is the author of the chapter Dutch.

- Council of Europe: Details of Treaty No.148: European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, see Reservations and declarations

- Driessen, Geert (2012). Ontwikkelingen in het gebruik van Fries, streektalen en dialecten in de periode 1995-2011 (PDF) (in Dutch). ITS, Radboud University Nijmegen. p. 3.

- "Nederlands in het Caribisch gebied en Suriname - Taalunie". taalunie.org (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- Statistiek, Centraal Bureau voor de. "Caribisch Nederland; gesproken talen en voertaal, persoonskenmerken". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- "Nederlands in het Caribisch gebied en Suriname - Taalunie". taalunie.org (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- "Indonesia and South Africa - Taalunie". taalunie.org (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- Driessen, Geert (2012): Ontwikkelingen in het gebruik van Fries, streektalen en dialecten in de periode 1995-2011. Nijmegen: ITS.

- Elmentaler, Michael ( ? ): "Die Schreibsprachgeschichte des Niederrheins. Forschungsprojekt der Uni Duisburg", in: Sprache und Literatur am Niederrhein, (Schriftenreihe der Niederrhein-Akademie Bd. 3, 15–34). (in German)

- Frins, Jean (2005): Syntaktische Besonderheiten im Aachener Dreiländereck. Eine Übersicht begleitet von einer Analyse aus politisch-gesellschaftlicher Sicht. Groningen: RUG Repro [Undergraduate Thesis, Groningen University] (in German)

- Frins, Jean (2006): Karolingisch-Fränkisch. Die plattdůtsche Volkssprache im Aachener Dreiländereck. Groningen: RUG Repro [Master's Thesis, Groningen University] (in German)

- Frings, Theodor (1916): Mittelfränkisch-niederfränkische Studien. I. Das ripuarisch-niederfränkische Übergangsgebiet. II. Zur Geschichte des Niederfränkischen, in: Beiträge zur Geschichte und Sprache der deutschen Literatur 41 (1916), 193–271; 42, 177–248.

- Hansche, Irmgard (2004): Atlas zur Geschichte des Niederrheins (= Schriftenreihe der Niederrhein-Akademie; 4). Bottrop/Essen: Peter Pomp. ISBN 3-89355-200-6

- Ludwig, Uwe & Schilp, Thomas (eds.) (2004): Mittelalter an Rhein und Maas. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Niederrheins. Dieter Geuenich zum 60. Geburtstag (= Studien zur Geschichte und Kultur Nordwesteuropas; 8). Münster/New York/München/Berlin: Waxmann. ISBN 3-8309-1380-X

- Mihm, Arend (1992): Sprache und Geschichte am unteren Niederrhein, in: Jahrbuch des Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung; 1992, 88–122.

- Mihm, Arend (2000): Rheinmaasländische Sprachgeschichte von 1500 bis 1650, in: Jürgen Macha, Elmar Neuss, Robert Peters (eds.): Rheinisch-Westfälische Sprachgeschichte. Köln (= Niederdeutsche Studien 46), 139–164.

- Tervooren, Helmut (2005): Van der Masen tot op den Rijn. Ein Handbuch zur Geschichte der volkssprachlichen mittelalterlichen Literatur im Raum von Rhein und Maas. Geldern: Erich Schmidt ISBN 3-503-07958-0