Ureteric stent

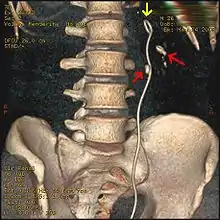

A ureteral stent (pronounced you-REE-ter-ul), or ureteric stent, is a thin tube inserted into the ureter to prevent or treat obstruction of the urine flow from the kidney. The length of the stents used in adult patients varies between 24 and 30 cm. Additionally, stents come in differing diameters or gauges, to fit different size ureters. The stent is usually inserted with the aid of a cystoscope. One or both ends of the stent may be coiled to prevent it from moving out of place; this is called a JJ stent, double J stent or pig-tail stent.

| Ureteric stent | |

|---|---|

Ureteral pigtail stent | |

| Pronunciation | you-REE-ter-ul |

| Specialty | urology |

Stent placement

Ureteral stents are used to ensure the openness of a ureter, which may be compromised, for example, by a kidney stone or a procedure. This method is sometimes used as a temporary measure, to prevent damage to a blocked kidney, until a procedure to remove the stone can be performed. Indwelling times of 12 months or longer are indicated to hold ureters open, which are compressed by tumors in the neighbourhood of the ureter or by tumors of the ureter itself. In many cases these tumors are inoperable and the stents are used to ensure drainage of urine through the ureter. If drainage is compromised for longer periods, the kidney can be damaged.

Stents may also be placed in a ureter that has been irritated or scratched during a ureteroscopy procedure that involves the removal of a stone, sometimes referred to as a 'basket grab procedure'. Stents placed for this reason are normally left in place for about a week. These stents ensure that the ureter does not spasm and collapse after the trauma of the procedure.

Contraindications

A technical drawback of ureteric stents is that they by-pass the 1-way valve at the entrance of the ureter into the bladder, the normal vesicoureteral (ureteral-bladder) junction. The function of this valve is to prevent backflow of urine from the bladder to the kidney (vesicoureteral reflux). A ureteric stent thus leads to the loss of the valve function thereby opening up the ureter to backflow. The main risk of such a backflow is the spreading of urinary tract infections up into the renal pelvis, which can then lead to an inflammation of the kidney (pyelonephritis). Such a condition, in turn, implies the risk of a life-threatening urosepsis (blood poisoning).

Ureteric stenting is therefore no option, if the patient shows conditions which favor a backflow of urine from the bladder to the kidney or if a urinary tract infection is present or suspected. Major such conditions are:[1]

- Actual or suspected urinary tract infection

- Obstruction of urine flow below the bladder (prostate enlargement by benign prostatic hyperplasia; narrowing of the urethra by urethral stricture): risk of backflow due to increased pressure in the bladder

- Overactive bladder: risk of backflow due to periods of increased pressure in the bladder

- Urinary incontinence: temporarily increased pressure in the bladder

Side effects and complications

The main complications with ureteral stents are dislocation, infection and blockage by encrustation. Recently stents with coatings, such as heparin, were approved to reduce infection and encrustation to reduce the number of stent exchanges.[2]

Other complications can include increased urgency and frequency of urination, blood in the urine, leakage of urine, pain in the kidney, bladder, or groin, and pain in the kidneys during, and for a short time after urination.[3] These effects are generally temporary and disappear with the removal of the stent. Drugs used for the treatment of OAB (over active bladder) are sometimes given to reduce or eliminate the increased urgency and frequency of urination caused by the presence of the stent.

Stents often have a thread, used for removal, that passes through the urethra and remains outside the body. This thread may cause irritation of the urethra. This may be increased for patients who were born with Hypospadias or other conditions that required a similar corrective surgery. Care must be taken to ensure that the thread is not caught or pulled, which may dislodge the stent.

While the stent is in place, patients may carry on with most normal activities; however, the stent may cause some discomfort during strenuous physical activity. Work and other daily activities may continue as normal. Sexual activity is also possible with a stent, but stents with a thread may significantly hinder sex.[3] The stent also can rest on the prostate gland in men, and with ejaculation/orgasm, the prostate may have movement that is discomforting to the patient, similar to severe cramping or irritation. One should approach sex differently with a stent, exercising caution.

Removal

Stents with a thread may be removed in a matter of a few seconds by pulling on the thread. This is often done by a nurse, but can be done by the patient. When removing the stent, constant, steady force should be applied, to avoid starting and stopping. Something should also be placed below the patient to catch any urine that leaks during removal. Stents without a thread are removed by a doctor using a cystoscope. The stent is removed by cystoscopy, an outpatient procedure. Cystoscopy involves placement of a small flexible tube through the urethra (the hole where urine exits the body). The procedure, which usually takes only a few minutes and causes little discomfort, is performed in an outpatient clinic or ambulatory surgery centre. Most patients tolerate having the stent removed using only a topical anesthetic placed in the urethra. Immediately before the procedure, sterile lubrication containing local anesthetic (lidocaine) is instilled into the urethra. Since no intravenous line is inserted and there is no anesthesia, the patient does not have to be accompanied by anyone else and they can eat normally before and after the procedure.

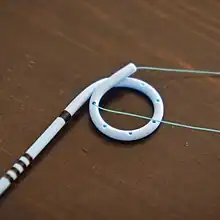

A ureteric stent may also be retrieved without the use of a cystoscope by means of a magnetic removal system. The stent inserted has a small rare earth magnet attached to its bladder end which dangles freely within the bladder. When the stent needs to be removed a small catheter with a similar magnet is inserted into the bladder and the two magnets connect and the catheter and stent can be simply removed. This eliminates the need for a costly and invasive cystoscopy in both adults and children.

Peer reviewed papers show that more than 98% of stents can be retrieved with a magnet in adults, paediatric and kidney transplant patients. Avoidance of a general anesthetic in children is very significant and also results in enormous cost-savings because the procedure no longer need to be done in the operating room.

Magnetic retrieval of the stent does not require a urologist and can be done by primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and nurses.

References

- J Urol Vol 168, 2023–2023, Nov 2002

- AUA University Series, abstract PD37-11

- Bedros Taslakian: Antegrade ureteral stenting. In: Bedros Taslakian, Aghiad Al-Kutoubi, Jamal J. Hoballah (Eds.): Procedural Dictations in Image-Guided Intervention. Non-Vascular, Vascular and Neuro Interventions. Springer, 2016, ISBN 978-3-319-40845-3, pp. 213–216.

- Furio Cauda, Valentina Cauda, Cristian Fiori, Barbara Onida, Edoardo Garrone, F; Cauda, V; Fiori, C; Onida, B; Garrone, E (2008), "Heparin Coating on Ureteral Double J Stents Prevents Encrustations: An in Vivo Case Study.", J Endourol., 22 (3): 465–472, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.612.1590, doi:10.1089/end.2007.0218, PMID 18307380

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - H. B. Joshi; N. Newns; F. X. Keeley Jr.; A. G. Timoney (2013-08-05), Uretic Stent

Further reading

- Ureteral stents- Materials; Endourology update: Mardis HK, Kroeger RM: Urological Clinics of North America, 1988, Vol. 15, No.3, 471–479.

- Ureteral stents – indications, variations and complications: Saltzman B: Endourology update : Urological Clinics of North America, 1988, Vol.15, No.3, 481–491.

- Self retained internal ureteral stents: Use and complications: Mardis HK: AUA update series, 1997, Lesson 29, Volume XVI.

- Macaluso JN (April 1993). "External urinary diversion: pathologic circumstances and available technology". J. Endourol. 7 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1089/end.1993.7.131. PMID 8518825.

- Having a Ureteric Stent - What to Expect and How to Manage. Authors: Mr. H. B. Joshi (Specialist Registrar in Urology, Cambridge. Formerly Research Registrar at Bristol Urological Institute), N. Newns (Staff Nurse), Mr. F. X. Keeley Jr. (Consultant Urologist), Mr. A. G. Timoney (Consultant Urologist), Bristol Urological Institute, Southmead Hospital, Westbury-on-trym, Bristol BS10 5NB

- Minimally invasive ureteric stent retrieval. W.N. Taylor. In "Stenting the Urinary System" 2E: Yachia, 2004, ISBN 1-84184-387-3 Martin Dunitz

- Minimally Invasive Ureteric Stent RetrievalTaylor WN, McDougall IT J Urol Vol 168,2020-2013, November 2002

- Magnetic Stent Removal in a Nurse-Led Clinic-O'Connell et al Ir Med J 2018 Feb 9, 111 (2) 687

- Comparison of a magnetic retrieval device vs. flexible cystoscopy for removal of ureteral stents in renal transplant patients: a randomised trial. Kapoor A et al. Can Urol Assoc J 2020 July EPub ahead of print.

- Use of a magnetic double J stent in pediatric patients: A case-control study at two Canadian centers. A. Mitchell et al J Ped Surg 2019 03. 014