Santa Muerte

Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte (Spanish: [ˈnwestɾa seˈɲoɾa ðe la ˈsanta ˈmweɾte]; Spanish for Our Lady of Holy Death), often shortened to Santa Muerte, is a cult image, female deity, and folk saint in folk Catholicism and Mexican Neopaganism.[1][2]: 296–297 A personification of death, she is associated with healing, protection, and safe delivery to the afterlife by her devotees.[3] Despite condemnation by leaders of the Catholic Church,[4] and more recently evangelical movements,[5] her cult[lower-alpha 1] has become increasingly prominent since the turn of the 21st century.[6]

| Our Lady of Holy Death Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte | |

|---|---|

Close-up of a Santa Muerte statue south of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas | |

| Other names | Lady of Shadows, Lady of the Night, White Lady, Black Lady, Skinny Lady, Bony Lady, Mictēcacihuātl (Lady of the Dead) |

| Affiliation | A wide variety of powers including love, prosperity, good health, fortune, healing, safe passage, protection against witchcraft, protection against assaults, protection against gun violence, protection against violent death |

| Major cult centre | Earliest temple is the Shrine of Most Holy Death founded by Enriqueta Romero in Mexico City |

| Weapon | Scythe |

| Artifacts | Globe, scale of justice, hourglass, oil lamp |

| Animals | Owl |

| Symbol | Human female skeleton clad in a robe |

| Region | Central America, Mexico, the (primarily Southwestern) United States, and Canada |

| Festivals | August 15 |

Originally appearing as a male figure,[7] Santa Muerte now generally appears as a skeletal female figure, clad in a long robe and holding one or more objects, usually a scythe and a globe.[8] Her robe can be of any color, as more specific images of the figure vary widely from devotee to devotee and according to the rite being performed or the petition being made.[9]

The following of Santa Muerte began in Mexico some time in the mid-20th century and was clandestine until the 1990s. Most prayers and other rites have been traditionally performed privately at home.[10] Since the beginning of the 21st century, worship has become more public, especially in Mexico City after a believer called Enriqueta Romero initiated her famous Mexico City shrine in 2001.[10][11][12] The number of believers in Santa Muerte has grown over the past ten to twenty years, to an estimated 10–20 million followers in Mexico, parts of Central America, the United States, and Canada. Santa Muerte has similar male counterparts in the American continent, such as the skeletal folk saints San La Muerte of Paraguay and Rey Pascual of Guatemala.[12] According to R. Andrew Chesnut, Ph.D. in Latin American history and professor of Religious studies, the cult of Santa Muerte is the single fastest-growing new religious movement in the Americas.[6]

Names

Santa Muerte can be translated into English as either "Saint Death" or "Holy Death", although the professor of Religious studies R. Andrew Chesnut believes that the former is a more accurate translation because it "better reveals" her identity as a folk saint.[13][14][15] A variant of this is Santísima Muerte, which is translated as "Most Holy Death" or "Most Saintly Death",[13] and devotees often call her Santisma Muerte during their rituals.[13]

Santa Muerte is also known by a wide variety of other names: the Skinny Lady (la Flaquita),[16] the Bony Lady (la Huesuda),[16] the White Girl (la Niña Blanca),[17] the White Sister (la Hermana Blanca),[13] the Pretty Girl (la Niña Bonita),[18] the Powerful Lady (la Dama Poderosa),[18] the Godmother (la Madrina),[17] Señora de las Sombras ("Lady of Shadows"), Señora Blanca ("White Lady"), Señora Negra ("Black Lady"), Niña Santa ("Holy Girl"), Santa Sebastiana ("Saint Sebastienne", i.e. "Holy Sebastian") or Doña Bella Sebastiana ("Beautiful Lady Sebastienne") and La Flaca ("The Skinny Woman").[19]

It has been recently suggested that the original Santa Muerta or Doña Sebastiana was, in fact, Doña Sebastiana de Caso y Paredes (b.1626), the niece of St. Mariana de Jesus of Quito (1618–1645), an Ecuadorian virgin penitent.[20] Sebastiana de Caso's birthday was August 15 (the traditional date of the feast day Santa Muerte),[21] and she was associated with the foundation of a pious society known as the Congregación de la Buena Muerte.[20] In the early devotional literature about the lives of Mariana and Sebastiana, it is related the father of Doña Sebastiana attempted to force her to marry against her will, but Sebastiana prayed earnestly to a personification of Death to be released from her predicament.[22] This prayer was answered, and Sebastiana soon succumbed to a fever and passed away. A spontaneous outpouring of veneration to her then emerged among both the native and colonist peoples of Quito.[20]

History

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the worship of death diminished but was never eradicated.[23] Judith Katia Perdigón Castañeda has found references dating to 18th-century Mexico. According to one account, recorded in the annals of the Spanish Inquisition, indigenous people in central Mexico tied up a skeletal figure, whom they addressed as "Santa Muerte," and threatened it with lashings if it did not perform miracles or grant their wishes.[12] Another syncretism between Pre-Columbian and Christian beliefs about death can be seen in Day of the Dead celebrations. During these celebrations, many Latin Americans flock to cemeteries to sing and pray for friends and family members who have died. Children partake in the festivities by eating chocolate or candy in the shape of skulls.[24] Perdigón Castañeda, Thompson, Kingsbury,[25] and Chesnut have countered the argument that Santa Muerte's origins are not Indigenous proposed by Malvido, Lomnitz, and Kristensen; stating that Santa Muerte's origins derive from authentic Indigenous beliefs. For Malvido this stems from Indigenist discourse originating in the 1930s. Nevertheless, through ethnoarchaeological researches by Kingsbury and Chesnut as well as archival work by Perdigón Castañeda, proof has been established that there are clear links between pre-Columbian death deity worship and Santa Muerte supplication. As Kingsbury has pointed out, to deny the Indigenous roots of Santa Muerte is to promote neo-colonialism and the denial of Indigenous influences and cultures as important still in the current context.

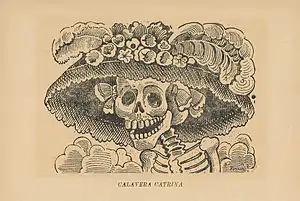

In contrast to the Day of the Dead, overt veneration of Santa Muerte remained clandestine until the middle of the 20th century. When it went public in sporadic occurrences, reaction was often harsh, and included the desecration of shrines and altars.[12] At the beginning of the 20th century, José Guadalupe Posada created a similar, but secular figure by the name of Catrina, a female skeleton dressed in fancy clothing of the period.[10] Posada began to evoke the idea that the universality of death generated a fundamental equality amongst man. His paintings of skeletons in daily life and that La Catrina were meant to represent the arbitrary and violent nature of an unequal society.[26]

Modern artists began to reestablish Posada's styles as a national artistic objective to push the limits of upper-class tastes; an example of Posada's influence is Diego Rivera's mural painting Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central, which features La Catrina. The image of the skeleton and the Day of the Dead ritual that used to be held underground became commercialized and domesticated. The skeletal images became that of folklore, encapsulating Posada's viewpoint that death is an equalizer.[26]

Skeletons were put in extravagant dresses with braids in their hair, altering the image of Posada's original La Catrina. As opposed to being the political message Posada intended, the skeletons of equality became skeletal images which were appealing to tourists and the national folkloric Mexican identity.[26]

Veneration of Santa Muerte was documented in the 1940s in working-class neighborhoods in Mexico City such as Tepito.[27] Other sources state that the revival has its origins around 1965 in the state of Hidalgo. At present Santa Muerte can be found throughout Mexico and also in parts of the United States and Central America.[12] There are videos, websites, and music composed in honor of this folk saint.[10] The cult of Santa Muerte first came to widespread popular attention in Mexico in August 1998, when police arrested notorious gangster Daniel Arizmendi López and discovered a shrine to the saint in his home. Widely reported in the press, this discovery inspired the common association between Santa Muerte, violence, and criminality in Mexican popular consciousness.[28]

Since 2001, there has been a "meteoric growth" in Santa Muerte belief, largely due to her reputation for performing miracles.[18] Worship has been made up of roughly two million adherents, mostly in the State of Mexico, Guerrero, Veracruz, Tamaulipas, Campeche, Morelos, and Mexico City, with a recent spread to Nuevo León.[10] In the late 2000s, the founder of Mexico City's first Santa Muerte church, David Romo, estimated that there were around 5 million devotees in Mexico, constituting approximately 5% of the country's population.[29]

By the late 2000s, Santa Muerte had become Mexico's second-most popular saint, after Saint Jude,[30] and had come to rival the country's "national patroness", the Virgin of Guadalupe.[18] The cult's rise was controversial, and in March 2009 the Mexican army demolished 40 roadside shrines near the U.S. border.[30] Circa 2005, the Santa Muerte cult was brought to the United States by Mexican and Central American immigrants, and by 2012 had tens of thousands of followers throughout the country, primarily in cities with high Hispanic and Latino populations.[31] As of 2016-2017, the Santa Muerte cult is considered to be one of the fastest-growing new religious movements in the world, with an estimated 10 to 12 million followers,[32] and the single fastest-growing new religious movement in the Americas.[6] The COVID-19 pandemic saw further growth in the Santa Muerte cult, as many believed that she would protect them against the virus.[33]

Attributes and iconography

Santa Muerte is a personification of death.[34] Unlike other saints who originated in Mexican folk Catholicism, Santa Muerte is not, herself, seen as a dead human being.[34] She is associated with healing, protection, financial wellbeing, and assurance of a path to the afterlife.[13]

Although there are other death saints in Latin America, such as San La Muerte, Santa Muerte is the only female saint of death in either of the Americas.[13] Though early figures of the saint were male,[7] iconographically, Santa Muerte is a skeleton dressed in female clothes or a shroud, and carrying both a scythe and a globe.[34][23] Santa Muerte is marked out as female not by her figure but by her attire and hair. The latter was introduced by a believer named Enriqueta Romero.[18]

The two most common objects that Santa Muerte holds in her hands are a globe and a scythe. Her scythe reflects her origins as the Grim Reaper (la Parca of medieval Spain),[12] and can represent the moment of death, when it is said to cut a silver thread. The scythe can symbolize the cutting of negative energies or influences. As a harvesting tool, a scythe may also symbolize hope and prosperity.[9] The scythe has a long handle, indicating that it can reach anywhere. The globe represents Death's vast power and dominion over the earth,[23] and may be seen as a kind of a tomb to which we all return.[9]

Other objects associated with Santa Muerte include scales, an hourglass, an owl, and an oil lamp.[9] The scales allude to equity, justice, and impartiality, as well as divine will.[23] An hourglass indicates the time of life on earth and also the belief that death is not the end, as the hourglass can be inverted to start over.[23] The hourglass denotes Santa Muerte's relationship with time as well as with the worlds above and below. It also symbolizes patience. An owl symbolizes her ability to navigate the darkness and her wisdom; the owl is also said to act as a messenger.[35] A lamp symbolizes intelligence and spirit, to light the way through the darkness of ignorance and doubt.[9] owls in particular are associated with Mesoamerican death deities such as Mictlantecuhtli and seen as evidence of continuity of death worship into Santa Muerte.[36] Some followers of Santa Muerte believe that she is jealous and that her image should not be placed next to those of other saints or deities, or there will be consequences.[24]

Many artists, particularly Mexican-American artists, have played with Santa Muerte's image. One of the images considered to be the most controversial in Mexico is the fusion of Santa Muerte and the Virgin of Guadalupe, into what is sometimes known as GuadaMuerte. This image has been very polemical for many Mexicans as it features Santa Muerte dressed like the Virgin, in blue veil with stars on it, red dress, with a fiery yellow halo behind her head and often in praying pose. It has, according to news sources, been so upsetting to the Catholic Church that Santa Muerte leaders in Mexico have advised against its use, while in the Santa Muerte community some leaders and devotees are angered that their powerful, formidable folk saint would be conflated with a completely separate entity and suffering female figure, the Virgin of Guadalupe, as the practices are different on many levels.[37][38]

Veneration

Rites associated with Santa Muerte

Rites dedicated to Santa Muerte include processions and prayers with the aim of gaining a favor.[11] Some believers of Santa Muerte remain members of the Catholic Church,[19] while others are cutting ties with the Catholic Church and founding independent Santa Muerte churches and temples.[39] Altars of Santa Muerte temples generally contain one or multiple images of the lady, generally surrounded by any or all of the following: cigarettes, flowers, fruit, incense, water, alcoholic beverages, coins, candies and candles.[23][11] Tobacco is also used for personal cleansing and for cleansing statues of Santa Muerte [40]

According to popular belief, Santa Muerte is very powerful and is reputed to grant many favors. Her images are treated as holy and can give favors in return for the faith of the believer, with miracles playing a vital role. As Señora de la Noche ("Lady of the Night"), she is often invoked by those exposed to the dangers of working at night, such as taxi drivers, bar owners, police, soldiers, and sex workers. As such, devotees believe she can protect against assaults, accidents, gun violence, and all types of violent death.[41]

The image is dressed differently depending on what is being requested. Usually, the vestments of the image are differently colored robes, but it is also common for the image to be dressed as a bride (for those seeking a husband)[23] or in European medieval nun's garments similar to female Catholic saints.[10] The colors of Santa Muerte's votive candles and vestments are associated with the type of petitions made.[42]

White is the most common color and can symbolize gratitude, purity, or the cleansing of negative influences. Red is for love and passion. It can also signify emotional stability. The color gold signifies economic power, success, money, and prosperity. Green symbolizes justice, legal matters, or unity with loved ones. Amber or dark yellow indicates health. Images with this color can be seen in rehabilitation centers, especially those for drug addiction and alcoholism.[43] Black represents total protection against black magic or sorcery, or conversely negative magic or for force directed against rivals and enemies. Blue candles and images of the saint indicate wisdom, which is favored by students and those in education. It can also be used to petition for health. Brown is used to invoke spirits from beyond while purple, like yellow, usually symbolizes health.[42] More recently black, purple, yellow and white candles have been used by devotees to supplicate Santa Muerte for healing of and protection from coronavirus as documented by Kingsbury and Chesnut, the leading researchers on Santa Muerte.[44] Other more recent colors include silver, transparent and red with black gown Santa Muerte which are used for particular petitions [45]

Devotees may present her with a polychrome seven-color candle, which Chesnut believed was probably adopted from the seven powers candle of Santería, a syncretic faith brought to Mexico by Cuban migrants.[46] Here the seven colors are gold, silver, copper, blue, purple, red, and green.[23][9] In addition to the candles and vestments, each devotee adorns their own image in their own way, using U.S. dollars, gold coins, jewelry, and other items.[11]

Santa Muerte also has a saint's day, which varies from shrine to shrine. The most prominent is November 1, when the believer Enriqueta Romero celebrates her at her historic Tepito shrine where the famous effigy is dressed as a bride.[19] Others celebrate her day on August 15.[23]

Places of worship

According to Chesnut, the cult of Santa Muerte is "generally informal and unorganized".[18] Since worship of this image has been, and to a large extent still is, clandestine, most rituals are performed in altars constructed at the homes of devotees.[10] Recently shrines to this image have been mushrooming in public. The one on Dr. Vertiz Street in Colonia Doctores is unique in Mexico City because it features an image of Jesús Malverde along with Santa Muerte. Another public shrine is in a small park on Matamoros Street very close to Paseo de la Reforma.[12]

Shrines can also be found in the back of all kinds of stores and gas stations. As veneration of Santa Muerte becomes more accepted, stores specializing in religious articles, such as botánicas, are carrying more and more paraphernalia related to the cult. Historian R. Andrew Chesnut has discovered that many botanicas in both Mexico and the U.S. are kept in business by sales of Santa Muerte paraphernalia, with numerous shops earning up to half of their profits on Santa Muerte items.[35] This is true even of stores in very well known locations such as Pasaje Catedral behind the Mexico City Cathedral, which is mostly dedicated to stores selling Catholic liturgical items. Her image is a staple in esoterica shops.[11]

There are those who now call themselves Santa Muerte priests or priestesses, such as Jackeline Rodríguez in Monterrey. She maintains a shop in Mercado Juárez in Monterrey, where tarot readers, curanderos, herbal healers, and sorcerers can also be found.[47]

Shrine of the Most Holy Death

The establishment of the first public shrine to the image began to change how Santa Muerte was venerated. The veneration has grown rapidly since then, and others have put their images on public display, as well.[10] In 2001, Enriqueta Romero built a shrine for a life-sized statue of Santa Muerte in her home in Mexico City, visible from the street. The shrine does not hold Catholic masses or occult rites, but people come here to pray and to leave offerings to the image.[19] The effigy is dressed in garbs of different colors depending on the season, with the Romero family changing the dress every first Monday of the month. This statue of the saint features large quantities of jewelry on her neck and arms, which are pinned to her clothing. It is surrounded by offerings left to it, including: flowers, fruits (especially apples), candles, toys, money, notes of thanks for prayers granted, cigarettes, and alcoholic beverages that surround it.[19]

Enriqueta Romero considers herself the chaplain of the shrine, a role she says she inherited from her aunt, who began the practice in the family in 1962.[19] The shrine is located on 12 Alfarería Street in Tepito, Colonia Morelos. For many, this Santa Muerte is the patron saint of Tepito.[27] The house also contains a shop that sells amulets, bracelets, medallions, books, images, and other items; the most popular item sold there is votive candles.[11]

On the first day of every month Enriqueta Romero or one of her sons lead prayers and the saying of the Santa Muerte rosary, which lasts for about an hour and is based on the Catholic rosary.[11][35] On the first of November the anniversary of the altar to Santa Muerte constructed by Enriqueta Romero is celebrated. This Santa Muerte is dressed as a bride and wears hundreds of pieces of gold jewelry given by the faithful to show gratitude for favors received, or to ask for one.[27]

The celebration officially begins at the stroke of midnight of November 1. About 5,000 faithful turn out to pray the rosary. For purification, the smoke of marijuana is used rather than incense, which is traditionally used for purification by Catholics. Food such as cake, chicken with mole, hot chocolate, coffee, and atole are served during the celebrations, which features performances by mariachis and marimba bands.[27]

Votive candles

Santa Muerte is a multifaceted saint, with various symbolic meanings and her devotees can call upon her a wide range of reasons. In herbal shops and markets one can find a plethora of Santa Muerte paraphernalia like the votive candles that have her image on the front and in a color representative of its purpose. On the back of the candles are prayers associated with the color's meaning and may sometimes come with additional prayer cards.[48] Color symbolism is central to devotion and ritual. There are three main colors associated with Santa Muerte: red, white, and black.[49]

The candles are placed on altars and devotees turn to specific colored candles depending on their circumstance. Some keep the full range of colored candles while others focus on one aspect of Santa Muerte's spirit. Santa Muerte is called upon for matters of the heart, health, money, wisdom, and justice. There is the brown candle of wisdom, the white candle of gratitude and consecration, the black candle for protection and vengeance, the red candle of love and passion, the gold candle for monetary affairs, the green candle for crime and justice, the purple candle for healing.[50]

The black votive candle is lit for prayer in order to implore La Flaca's protection and vengeance. It is associated with "black magic" and witchcraft. It is not regularly seen at devotional sites, and is usually kept and lit in the privacy of one's home. To avert from calling upon official Catholic saints for illegal purpose, drug traffickers will light Santa Muerte's black candle to ensure protection of shipment of drugs across the border.[50] Nevertheless, black candles may also be used for more benign activities such as reversing spells, as well as all forms of protection and removing energetic blockages.[49]

Black candles are presented to Santa Muerte's altars that drug traffickers used to ensure protection from violence of rival gangs as well as ensure harm to their enemies in gangs and law enforcement. As the drug war in Mexico escalates, Santa Muerte's veneration by drug bosses increases and her image is seen again and again in various drug houses. Ironically, the military and police officers that are employed to dismantle the White Lady's shrines make up a large portion of her devotees. Furthermore, even though her presence in the drug world is becoming routine, the sale of black candles pales in comparison to top selling white, red, and gold candles.[51]

One of Santa Muerte's more popular uses is in matters of the heart. The red candle that symbolizes love is helpful in various situations having to do with love. Her initial main purpose was in love magic during the colonial era in Mexico, which may have been derived from the love magic being brought over from Europe. Her origins are still unclear but it is possible that the image of the European Grim Reaper combined with the indigenous celebrations of death are at the root of La Flaca's existence, in so that the use of love magic in Europe and that of pre-Columbian times that was also merging during colonization may have established the saint as manipulator of love.[48]

The majority of anthropological writings on Santa Muerte discuss her significance as provider of love magic and miracles.[52] The candle can be lit for Santa Muerte to attract a certain lover and ensure their love. In contrast though, the red candle can be prayed to for help in ending a bad relationship in order to start another one. These love miracles require specific rituals to increase their love doctors power. The rituals require several ingredients including red roses and rose water for passion, binding stick to unite the lovers, cinnamon for prosperity, and several others depending on the specific ritual.[52]

In the United States

The cult of Santa Muerte was established in the United States c. 2005, brought to the country by Mexican and Central American migrants.[53] American scholar of religious studies Andrew Chesnut suggests that there were tens of thousands of devotees in the U.S. by 2012.[54] This cult is primarily visible in cities with high Hispanic and Latino populations, such as New York City, Chicago, Houston, San Antonio, Tucson, and Los Angeles.[24][14] There are fifteen religious groups dedicated to her in Los Angeles alone,[23] which include the Temple of Santa Muerte on Melrose Avenue in East Hollywood.[55]

In some places, such as Northern California and New Orleans, her popularity has spread beyond the Hispanic and Latino community. For instance, the Santisima Muerte Chapel of Perpetual Pilgrimage is maintained by a woman of Danish descent, while the New Orleans Chapel of the Santisima Muerte was founded in 2012 by a Non-Hispanic White devotee.[56][57]

As in Mexico, some elements of the Catholic Church in the United States are trying to combat Santa Muerte worship, in Chicago particularly.[24][14][58][59] Compared to the Catholic Church in Mexico, the official reaction in the U.S. is mostly either nonexistent or muted. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has not issued an official position on this relatively new phenomenon in the country.[14] Opposition to the veneration of Santa Muerte took a violent turn in late January, 2013, when one or more vandals smashed a statue of the folk saint, which had appeared in the San Benito, Texas, municipal cemetery earlier that month.[60]

Sociology

The cult of Santa Muerte is present throughout the strata of Mexican society, although the majority of devotees are either underemployed workers or from the urban working class.[15][61] Most are young people, aged in their teens, twenties, or thirties, and are also mostly female.[15][53] A large following developed among Mexicans who are disillusioned with the dominant, institutional Catholic Church and, in particular, with the inability of established Catholic saints to deliver them from poverty.[14][15]

The phenomenon is based mostly among people with scarce resources, excluded from the formal market economy, as well as the judicial and educational systems, primarily in the inner cities and the very rural areas.[23] Devotion to Santa Muerte is what anthropologists call a "cult of crisis". Devotion to the image peaks during economic and social hardships, which tend to affect the working classes more.[15] Santa Muerte tends to attract those in extremely difficult or hopeless situations but also appeals to smaller sectors of middle class professionals and even the affluent.[10][42] Some of her most devoted followers are outcasts who commit petty economic crimes, often committed out of desperation, such as sex workers and petty thieves.[15][23]

The worship of Santa Muerte also attracts those who are not inclined to seek the traditional Catholic Church for spiritual solace, as it is part of the "legitimate" sector of society; many followers of Santa Muerte live on the margins of the law or outside it entirely.[15] Many street vendors, taxi drivers, vendors of counterfeit merchandise, street people, sex workers, pickpockets, petty drug traffickers and gang members who follow the cult are not practicing Catholics or Protestants, but neither are they atheists.[15][23]

In essence they have created their own new religion that reflects their realities, hardships, identity, and practices, especially since it speaks to the violence and struggles for life that many of these people face.[15][23] Conversely, both police forces and the military in Mexico can be counted among the faithful who ask for blessings on their weapons and ammunition.[23]

While worship is largely based in poor neighborhoods, Santa Muerte is also venerated in affluent areas such as Mexico City's Condesa and Coyoacán districts.[62] However, negative media coverage of the worship and condemnation by the Catholic Church in Mexico and certain Protestant denominations have influenced public perception of the cult of Santa Muerte. With the exception of some artists and politicians, some of whom perform rituals secretly, those in higher socioeconomic strata look upon the veneration with distaste as a form of superstition.[10]

Association with the LGBTQ+ community

Santa Muerte is also revered and seen as a saint and protector of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) communities in Mexico,[15][63][64][65][66] since LGBTQ+ people are considered and treated as outcasts by the Catholic Church, evangelical churches, and Mexican society at large.[15][63] Many LGBTQ+ people ask her for protection from violence, hatred, disease, and to help them in their search for love. Her intercession is commonly invoked in same-sex marriage ceremonies performed in Mexico.[67][68] The Iglesia Católica Tradicional México-Estados Unidos, also known as the Church of Santa Muerte, recognizes gay marriage and performs religious wedding ceremonies for homosexual couples.[69][70][71][72]

Association with criminality

In the Mexican and U.S. press, the cult of Santa Muerte is often associated with violence, criminality, and the illegal drug trade.[73] She is a popular deity in prisons, both among inmates and staff, and shrines dedicated to her can be found in many cells.[74][62][75]

Altars with images of Santa Muerte have been found in many drug houses in both Mexico and the United States.[23] Among Santa Muerte's more famous devotees are kidnapper Daniel Arizmendi López, known as El Mochaorejas, and Gilberto García Mena, one of the bosses of the Gulf Cartel.[62][75] In March 2012, the Sonora State Investigative Police announced that they had arrested eight people for murder for allegedly having performed a human sacrifice of a woman and two ten-year-old boys to Santa Muerte (see: Silvia Meraz).[76]

In December 2010, the self-proclaimed bishop David Romo was arrested on charges of banking funds of a kidnapping gang linked to a cartel. He continues to lead his sect from his prison, but it is unfeasible for Romo or anyone else to gain dominance over the Santa Muerte cult. Her faith is spreading rapidly and "organically" from town to town, such that it is easy to become a preacher or messianic figure. Drug lords, like that of La Familia Cartel, take advantage of "gangster foot soldiers'" vulnerability and enforced religious obedience to establish a holy meaning to their cause that would keep their soldiers disciplined.[77]

Opposition and persecution

Since the mid-20th century and throughout the 21st century, the cult of Santa Muerte and her devotees have been regularly discriminated, ostracized, and socially excluded both by the Catholic Church and various evangelical-Pentecostal Protestant churches in Mexico and the rest of Central America.[78][79][80][81]

The Catholic Church has condemned the cult of Santa Muerte in Mexico and Latin America as blasphemous and satanic,[24] calling it a "degeneration of religion".[82] When Pope Francis visited Mexico in 2016, he repudiated Santa Muerte on his first full day in the country, condemning Santa Muerte as a dangerous symbol of narco-culture.[83]

Latin American Protestant churches have condemned it too, as black magic and trickery.[10] Mexico's Catholic Church has accused Santa Muerte devotees—many of whom were baptized in the Catholic religion despite the difference of belief and the fact that Santa Muerte churches and temples have instituted a separate baptism practice—of having turned to devil-worship.[14]

Catholic priests regularly chastise parishioners, telling them that death is not a person but rather a phase of life.[10] However, the Church stops short of labeling such followers as heretics, instead accusing them of heterodoxy.[84] Other reasons the Mexican Catholic Church has officially condemned the worship of Santa Muerte is that most of her rites are modeled after Catholic liturgy,[23] and some Santa Muerte devotees eventually split from the Catholic Church and began vying for control of church buildings.[14]

Despite the many attempts from the Catholic Church and Protestant churches to undermine the devotion to Santa Muerte in Mexico and elsewhere, along with the religious discrimination and accusations towards her followers, the cult of Santa Muerte has enjoyed a steady growth and spread in the American continent since the mid-20th century, and is considered by scholars of religion to be the single fastest-growing new religious movement in the Americas.[6][78][79]

Popular culture

- In the 2017 video game Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon Wildlands, members of the Mexican drug cartel known as the Santa Blanca Cartel are followers of Santa Muerte.

- In the opening scene of Breaking Bad Season 3 (No Más), the Salamanca Twins leave an offering at a shrine of Santa Muerte before travelling north to seek revenge for the death of their cousin Tuco.

See also

Notes

- The term cult, when used in the context of religion, refers to the worship or veneration of certain deities and the rites associated with them. It does not hold the negative connotations that the word has in colloquialism. Also, in Catholicism, outward religious practice in cultus is the technical term for Roman Catholic devotions or veneration extended to a particular saint. As such, when the word "cult" is used in this article, it refers to the devotion, veneration, and rituals associated with Santa Muerte. The reason the word "cult" is used rather than "religion" is because the veneration of Santa Muerte is not its own religion, but rather a branch of folk-Catholicism.

References

- Chesnut, R. Andrew (2016). "Healed by Death: Santa Muerte, the Curandera". In Hunt, Stephen J. (ed.). Handbook of Global Contemporary Christianity: Movements, Institutions, and Allegiance. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 12. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 336–353. doi:10.1163/9789004310780_017. ISBN 978-90-04-26539-4. ISSN 1874-6691.

- Flores Martos, Juan Antonio (2007). "La Santísima Muerte en Veracruz, México: Vidas Descarnadas y Práticas Encarnadas". In Flores Martos, Juan Antonio; González, Luisa Abad (eds.). Etnografías de la muerte y las culturas en América Latina (in Spanish). Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla–La Mancha. pp. 273–304. ISBN 978-84-8427-578-7.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 6–7.

- Kingsbury and Chesnut 2019, The Church's life-and-death struggle with Santa Muerte, The Catholic Herald

- Kingsbury and Chesnut 2020, Colonizing Death -American Evangelist Crusades Against Santa Muerte at Landmark Shrine in Tepito, Global Catholic Review

- Chesnut, R. Andrew (26 October 2017). Santa Muerte: The Fastest Growing New Religious Movement in the Americas (Speech). Lecture. Portland, Oregon: University of Portland. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Guillermoprieto, Alma (14 May 2013). "Vatican in a Bind About Santa Muerte". National Geographic News. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Los Angeles believers in La Santa Muerte say they aren't a cult | The Madeleine Brand Show | 89.3 KPCC". 66.226.4.226. 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- Velazquez, Oriana (2007). El libro de la Santa Muerte [The book of Santa Muerte] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-968-15-2040-3.

- Garma, Carlos (2009-04-10). "El culto a la Santa Muerte" [The cult of Santa Muerte]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Villarreal, Hector (2009-04-05). "La Guerra Santa de la Santa Muerte" [The Holy War of Santa Muerte]. Milenio semana (in Spanish). Mexico City: Milenio. Archived from the original on 2009-10-16. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 26–50.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 7.

- Gray, Steven (2007-10-16). "Santa Muerte: The New God in Town". Time.com. Chicago: Time. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Lorentzen, Lois Ann (2016). Pellegrini, Anna; Vaggione, Juan Marco (eds.). "Santa Muerte: Saint of the Dispossessed, Enemy of Church and State". Emisférica. Vol. 13, no. 1. New York City: Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 3.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 5.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 8.

- Velazquez, Oriana (2007). El libro de la Santa Muerte [The book of Santa Muerte] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-968-15-2040-3.

- Nixon, Robert (2022). The Venerable Doña Sebastiana de Caso: the original Santa Muerte. West Yorkshire: Hadean Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-914166-58-7.

- Morán de Butrón, Jacinto (1856). Vida del la Beata Mariana (in Spanish). Madrid. p. 71.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Morán de Butrón, Jacinto (1856). Vida del la Beata Mariana (in Spanish). Madrid. p. 74.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Araujo Peña, Sandra Alejandro; Barbosa Ramírez Marisela; Galván Falcón Susana; García Ortiz Aurea; Uribe Ordaz Carlos. "El culto a la Santa Muerte: un estudio descriptivo" [The Santa Muerte Cult:A descriptive study]. Revista Psichologia (in Spanish). Mexico City: Universidad de Londres. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Ramirez, Margaret. "'Saint Death' comes to Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Chicago. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Kingsbury, Kate; Chesnut, R. Andrew (2021). "Syncretic Santa Muerte: Holy Death and Religious Bricolage". Religions. 12 (3): 220. doi:10.3390/rel12030220.

- Fragoso, Perla (2011). "De la "calavera domada" a la subversión santificada. La Santa Muerte, un nuevo imaginario religioso en México" (PDF). Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana Unidad Azcapotzalco. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- "La Santa Muerte de Tepito cumple seis años" [The Santa Muerte of Tepito turns six] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Radio Trece. Archived from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 15–16.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 8–9.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 4.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 9–11.

- Chesnut, R. Andrew (6 October 2015). "Mexico's Top Two Santa Muerte Leaders Finally Meet". HuffPost. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- Brogan, Mary Kate (26 August 2022). "Scholar says Santa Muerte, 'the newest plague saint,' has been a beacon of hope during COVID-19". VCU News. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 6.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 50–97.

- "Mictlantecuhtli, Aztec God of Death – Mexico Unexplained". 9 December 2019.

- https://wrldrels.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Interview-with-R.-Andrew-Chesnut.pdf

- Lara, Bravo; Estela, Blanca (December 2013). "Bajo tu manto nos acogemos: Devotos a la Santa Muerte en la zona metropolitana de Guadalajara". Nueva Antropología. 26 (79): 11–28.

- "The Rise of Santa Muerte Worship and Demon Exorcism in Mexico – VICE – United States". 28 September 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- Cressida Stone, "Secrets of Santa Muerte", 2020, Weiser Press

- Velazquez, Oriana (2007). El libro de la Santa Muerte [The book of Santa Muerte] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-968-15-2040-3.

- "World Religions & Spirituality | Cronica De La Santa Muerte". Has.vcu.edu. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 147–175.

- Kingsbury, Kate; Chesnut, R. Andrew (September 2020). "Holy Death in the Time of Coronavirus: Santa Muerte, the Salubrious Saint". International Journal of Latin American Religions. Nature Public Health Emergency Collection. University of Toronto Press. 4 (1): 194–217. doi:10.1007/s41603-020-00110-6. ISSN 2509-9965. PMC 7485595. S2CID 221656092.

- see Cressida Stone, "Secrets of Santa Muerte: A Guide to the Prayers, Rituals and Hexes", 2020 Weiser Press

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 19–20, 26.

- Harden Cooper, Ricardo (2008-02-14). "Vende bien aquí la Santa Muerte" [Santa Muerte sells well here]. El Porvenir (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Thompson, John (Winter 1998). "Santísma Muerte: Origin and Development of a Mexican Occult Image". Journal of the Southwest. 40 (4).

- Kingsbury, Kate and Chesnut, R. Andrew 2019, Mexican Folk Saint Santa Muerte – The Fastest Growing New Religious Movement in the West

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 3–27.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 102–103.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 133–147, 175–192.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 13.

- Chesnut 2018, p. 11.

- "Templo a la Santa Muerte". Archived from the original on 2009-05-22. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- "Santisima Muerte Chapel of Perpetual Pilgrimage". Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- "The New Orleans Chapel of the Santisima Muerte". Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- Martin, Michelle (2012-02-19). "Our Lady of Guadalupe battles 'Holy Death' for devotion of Mexican faithful". Our Sunday Visitor. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17.

- Lorentzen, Lois Ann (2009-05-28). "Holy Death on the US/Mexico Border". The University of Chicago Divinity School.

- Rodriguez, Michael; Jimenez, Francisco E. (2013-01-25). Q&A – Occult experts weigh in on Saint Death's 'desecration'. San Benito News, 25 January 2013. Retrieved from https://news.yahoo.com/q-occult-experts-weigh-saint-015947105.html.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 11–12.

- Pacheco Colín, Ricardo. "El culto a la Santa Muerte pasa de Tepito a Coyoacán y la Condesa" [The Santa Muerte cult moves from Tepito to Coyoacan and Condesa]. La Cronica de Hoy (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- Bárcenas Barajas, Karina (September–December 2019). "Apropiaciones LGBT de la religiosidad popular" (PDF). Desacatos: Revista de Ciencias Sociales (in Spanish). Mexico City: Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS). 61: 98–113. doi:10.29340/61.2135 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 2448-5144. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Woodman, Stephen (31 March 2017). "How a skeleton folk saint of death took off with Mexican transgender women". USA Today. ISSN 0734-7456. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- Villarreal, Daniel (6 April 2019). "Bishops tell Catholics to stop worshipping this unofficial LGBTQ-friendly saint of death: Even though "La Santa Muerte" is not a Church-sanctioned saint, millions of people still revere her". LGBTQ Nation. San Francisco. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- "Archives". outinthebay.com. Out In The Bay. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-04-24.

- "Iglesia de Santa Muerte casa a gays". El Universal – Sociedad. 2010-03-03. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- (México) Sociedad–Salud > Area: Asuntos sociales. "La Iglesia de Santa Muerte mexicana celebró su primera boda gay y prevé 9 más". ABC.es – Noticias Agencias. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "La Nueva Iglesia De La Santa Muerte Permite Bodas Gay". Los21.com. 2012-01-24. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- "La Santa Muerte celebra "bodas homosexuales" en México - México y Tradición" (in Spanish). Mexicoytradicion.over-blog.org. 2010-06-02. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- "Culto a la santa muerte casará a gays". Tendenciagay.com. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- "Mexico's Holy Death Church Will Conduct Gay Weddings". Latin American Herald Tribune. 2010-01-07.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 10, 14.

- Chesnut 2018, pp. 14–15.

- Chesnut, R. Andrew; Borealis, Sarah (2012-02-20). Santa Muerte – Cronica de la Santa Muerte – Santa Muerte Timeline. World Religions & Spirituality Project VCU, Virginia Commonwealth University, 20 January 2012. Retrieved from http://www.has.vcu.edu/wrs/profiles/SantaMuerte.htm.

- "Officials: 3 killed as human sacrifices in Mexico". CNN.com. CNN. 2012-03-30. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2012-04-03.

- Grillo, Ioan (2011). El Narco. Bloomsbury Press.

- Chesnut, R. Andrew; Yllescas, Jorge Adrián (2018). "Santa Muerte". In Blancarte, Roberto (ed.). Diccionario de Religiones en América Latina (in Spanish). Mexico City: El Colegio de México/Fondo de Cultura Económica. pp. 573–585. ISBN 978-607-628-389-9.

- Bromley, David G. (June 2016). Chesnut, R. Andrew; Metcalfe, David (eds.). "Santa Muerte as Emerging Dangerous Religion?". Religions. Basel: MDPI. 7 (6: 'Death in the New World: The Rise of Santa Muerte'): 65. doi:10.3390/rel7060065. eISSN 2077-1444.

- Gaytán Alcalá, Felipe (January–June 2008). "Santa entre los Malditos: Culto a La Santa Muerte en el México del siglo XXI". LiminaR: Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica (CESMECA) – Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. 6 (1): 40–51. doi:10.29043/liminar.v6i1.265. eISSN 2007-8900. ISSN 1665-8027. S2CID 142525950.

- Perdigón Castañeda, Judith K. (January–June 2008). "Una relación simbiótica entre La Santa Muerte y El Niño de las Suertes". LiminaR: Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica (CESMECA) - Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. 6 (1): 52–70. doi:10.29043/liminar.v6i1.266. eISSN 2007-8900. ISSN 1665-8027. S2CID 143388890.

- "Vatican declares Mexican Death Saint blasphemous". Bbc.co.uk. 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- Kingsbury, Kate and Chesnut, R. Andrew 2019 The Church's life-and-death struggle with Santa Muerte

- Garcia Meza, Daniel (2008-11-01). "La "Niña blanca" mejor conocida como La Santa Muerte" [The White Girl, better known as Santa Muerte]. El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). Torreon, Mexico. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

Bibliography

Academic journals

- Bastante, Pamela; Dickieson, Brenton (Winter 2013). "Nuestra Señora de las Sombras: The Enigmatic Identity of Santa Muerte". Journal of the Southwest. Tucson: Southwest Center at the University of Arizona. 55 (4): 435–471. doi:10.1353/JSW.2013.0010. ISSN 2158-1371. JSTOR 24394940. S2CID 110098311.

- Bromley, David G. (June 2016). Chesnut, R. Andrew; Metcalfe, David (eds.). "Santa Muerte as Emerging Dangerous Religion?". Religions. Basel: MDPI. 7 (6: Death in the New World: The Rise of Santa Muerte): 65. doi:10.3390/rel7060065. eISSN 2077-1444.

- Gaytán Alcalá, Felipe (January–June 2008). "Santa entre los Malditos: Culto a La Santa Muerte en el México del siglo XXI". LiminaR: Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica (CESMECA) – Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. 6 (1): 40–51. doi:10.29043/liminar.v6i1.265. eISSN 2007-8900. ISSN 1665-8027. S2CID 142525950.

- González, César R. (2019). "La Santa Muerte: symbole et dévotion envers "la reine des épouvantables"/Santa Muerte: Symbolism and devotion to the "Lady of Holy Death"". Sociétés (in French). Paris: De Boeck Supérieur. 4 (146): 91–103. doi:10.3917/soc.146.0091. ISSN 0765-3697. S2CID 213290072 – via Cairn.info.

- Higuera-Bonfil, Antonio (July–December 2015). "Fiestas en honor a la Santa Muerte en el Caribe mexicano". LiminaR: Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica (CESMECA) – Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. 13 (2): 96–109. doi:10.29043/liminar.v13I2.395. eISSN 2007-8900. ISSN 1665-8027. S2CID 143369628.

- Kingsbury, Kate; Chesnut, R. Andrew (March 2021). Oleszkiewicz-Peralba, Małgorzata (ed.). "Syncretic Santa Muerte: Holy Death and Religious Bricolage". Religions. Basel: MDPI. 12 (3: Syncretism and Liminality in Latin American and Latinx Religions): 220. doi:10.3390/rel12030220. eISSN 2077-1444.

- Kingsbury, Kate; Chesnut, R. Andrew (December 2020). Boudreault-Fournier, Alexandrine (ed.). "Santa Muerte: Sainte Matronne de l'Amour et de la Mort". Anthropologica. University of Toronto Press. 62 (2): 380–393. doi:10.3138/anth-2019-0004. ISSN 2292-3586. LCCN 56004160. OCLC 610393076. S2CID 231625165.

- Kingsbury, Kate; Chesnut, R. Andrew (September 2020). Usarski, Frank (ed.). "Holy Death in the Time of Coronavirus: Santa Muerte, the Salubrious Saint". International Journal of Latin American Religions. Berlin: Springer Nature. 4 (1): 194–217. doi:10.1007/s41603-020-00110-6. eISSN 2509-9965. ISSN 2509-9957. PMC 7485595. S2CID 221656092.

- Kingsbury, Kate (July 2020). Usarski, Frank (ed.). "Death is Women's Work: Santa Muerte, a Folk Saint and Her Female Followers". International Journal of Latin American Religions. Berlin: Springer Nature. 4 (1): 43–63. doi:10.1007/s41603-020-00106-2. eISSN 2509-9965. ISSN 2509-9957. S2CID 225572498.

- Kingsbury, Kate; Chesnut, R. Andrew (February 2020). Usarski, Frank (ed.). "Not Just a Narcosaint: Santa Muerte as Matron Saint of the Mexican Drug War". International Journal of Latin American Religions. Berlin: Springer Nature. 4 (1): 25–47. doi:10.1007/s41603-020-00095-2. eISSN 2509-9965. ISSN 2509-9957. S2CID 213417007.

- Kristensen, Regnar A. (February 2015). Jones, Gareth; Macaulay, Fiona; Miller, Rory (eds.). "La Santa Muerte in Mexico City: The Cult and its Ambiguities". Journal of Latin American Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 47 (3): 543–566. doi:10.1017/S0022216X15000024. ISSN 1469-767X. LCCN 79008163. OCLC 01800137. S2CID 145524640.

- Kristensen, Regnar A. (August 2014). "How did Death become a Saint in Mexico?". Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology. Taylor & Francis. 81 (3): 402–424. doi:10.1080/00141844.2014.938093. S2CID 143603099.

- Marrero, Roberto Garcés (December 2019). "La Santa Muerte en la Ciudad de México: Devoción, vida cotidiana y espacio público/La Santa Muerte in Mexico City: Devotion, everyday life and public space". Revista Cultura & Religión (in Spanish). Instituto de Estudios Internacionales (Universidad Arturo Prat). 13 (2): 103–121. doi:10.4067/S0718-47272019000200103. ISSN 0718-4727. S2CID 213065454.

- Martin, Desirée A. (March 2017). Chesnut, R. Andrew; Metcalfe, David (eds.). ""Santísima Muerte, Vístete de Negro, Santísima Muerte, Vístete de Blanco": La Santa Muerte's Illegal Marginalizations". Religions. Basel: MDPI. 8 (3): 36. doi:10.3390/rel8030036. eISSN 2077-1444.

- Michalik, Piotr Grzegorz (January–March 2011). "Death with a Bonus Pack: New Age Spirituality, Folk Catholicism, and the Cult of Santa Muerte" (PDF). Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions. Paris: Éditions de l'EHESS. 153 (1): 159–182. doi:10.4000/assr.22800. ISBN 978-2-71322301-3. ISSN 1777-5825. JSTOR 41336081. S2CID 144847868.

- Perdigón Castañeda, Judith K. (December 2015). "La indumentaria para La Santa Muerte". Cuicuilco: Revista de la Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia (in Spanish). Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (CONACULTA). 22 (64): 43–62. ISSN 1405-7778. S2CID 192520236.

- Perdigón Castañeda, Judith K. (January–June 2008). "Una relación simbiótica entre La Santa Muerte y El Niño de las Suertes". LiminaR: Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica (CESMECA) – Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. 6 (1): 52–70. doi:10.29043/liminar.v6i1.266. eISSN 2007-8900. ISSN 1665-8027. S2CID 143388890.

- Reyes-Cortez, Marcel (March 2012). "Material culture, magic, and the Santa Muerte in the cemeteries of a megalopolis". Culture and Religion. Taylor & Francis. 13 (1): 107–131. doi:10.1080/14755610.2012.658420. OCLC 223320203. S2CID 145194760.

- Torres-Ramos, Gabriela (2015). Souffron, Valérie (ed.). "Un culte populaire au Mexique: la Santa Muerte". Socio-anthropologie (in French). Paris: Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. 31 (31): 139–150. doi:10.4000/socio-anthropologie.2228. eISSN 1773-018X. ISBN 978-2-85944-913-1.

Monographs, poetry, and essays

- Aridjis, Homero (2017) [2004]. La Santa Muerte/Holy Death. New York: Penguin Random House. ISBN 9786073150736.

- Chesnut, R. Andrew (2018) [2012]. Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint (Second ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199764662.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-063332-5. LCCN 2011009177.

- Flores Martos, Juan A. (2008). "Transformismos y transculturación de un culto novomestizo emergente: La Santa Muerte Mexicana" (PDF). In Cornejo Valle, Mónica; Cantón Delgado, Manuela; Llera Blanes, Ruy (eds.). Teorías y prácticas emergentes en antropología de la religión. XI Congreso de Antropología de la FAAEE (in Spanish). Donostia: Ankulegi Antropologia Elkartea. pp. 55–76. ISBN 978-84-691-4962-1.

- Higuera-Bonfil, Antonio (2016). "La religión transterrada. El culto a la Santa Muerte en Nueva York". In Hernández, Alberto Hernández (ed.). La Santa Muerte. Espacios, cultos y devociones (in Spanish). Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte/El Colegio de San Luis. pp. 229–251. ISBN 978-607-479-238-6. OCLC 978293392.

- Lorusso, Fabrizio; Evangelisti, Valerio (2013). Santa Muerte. Patrona dell'umanità. Eretica speciale (in Italian). Tarquinia: Stampa Alternativa/Nuovi Equilibri. ISBN 978-8862223300.

- Müller, Silke (2021). "La Santa Muerte" – Leben mit dem Tod. Eine Soziologie der Verehrung. Kulturen der Gesellschaft (in German). Vol. 46. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8376-5513-1.

- Oleszkiewicz-Peralba, Małgorzata (2015). "Santa Muerte, Death the Protector". Fierce Feminine Divinities of Eurasia and Latin America: Baba Yaga, Kālī, Pombagira, and Santa Muerte. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 103–135. doi:10.1057/9781137535009_5. ISBN 978-1-137-54354-7. S2CID 163422636.

- Pansters, Wil G., ed. (2019). La Santa Muerte in Mexico: History, Devotion, and Society. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-6081-6. OCLC 1105750108. S2CID 211582359.

- Perdigón Castañeda, Judith K.; Sáinz, Luis Ignacio (2008). La Santa Muerte, protectora de los Hombres (in Spanish). Distrito Federal (Mexico): Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (CONACULTA). ISBN 978-968-03-0306-9. OCLC 259744376.

- Stone, Cressida (2022). Secrets of Santa Muerte: A guide to the Prayers, rituals and hexes. New York: Red Wheel Weiser. ISBN 9781578637720.

- Velázquez, Eduardo G.; García-Villada, Eduardo; Knepper, Timothy D. (2019). "The Cult of Santa Muerte: Migration, Marginalization, and Medicalization". In Knepper, Timothy D.; Bregman, Lucy; Gottschalk, Mary (eds.). Death and Dying. Comparative Philosophy of Religion. Vol. 2. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. pp. 63–76. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-19300-3_5. eISSN 2522-0039. ISBN 978-3-030-19299-0. ISSN 2522-0020. S2CID 203054002.

External links

- La Santa Muerte, Full-length documentary about Santa Muerte, Spanish, English subtitles.

- Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint, Dr. R. Andrew Chesnut's book talk at the Library of Congress

- Santa Muerte a photo essay from Mexico City

- Kingsbury, Kate and Chesnut, R. Andrew on Santa Muerte

- "La Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint article on Atlas Obscura

- Nuestra Santisima Muerte A documentary online