Dives and Pauper

Dives and Pauper is a 15th-century commentary and exposition on the Ten Commandments written in dialogue form.[1] Written in Middle English, while the identity of the author is unknown, the text is speculated to have been authored by a Franciscan friar.[2] Dives and Pauper is structured as a dialogue between two interlocutors, a wealthy layman (Dives) and a spiritual poor man with many similarities to a friar (Pauper). The text engages with orthodox Catholic theology, and further discusses many questions relevant to Wycliffism, an English movement which criticised doctrines and abuses of the Church, which was condemned as heretical by church authorities.[3]

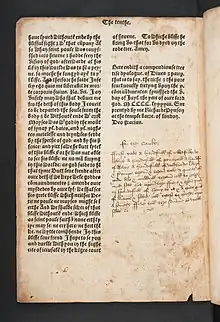

Final page of printed Dives and Pauper with colophon providing title and imprint details. A 16th-century manuscript note gives a recipe supposed to cure “the canker”. | |

| Author | Unknown |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | Middle English |

| Genre | Middle-English Literature |

| Published | 15th century (approx. 1402–1405) |

| Media type | Commentary |

Like John Wycliffe's De mandatis divinis, Dives and Pauper discusses each of the Ten Commandments in the context of Church law, as well as the "laws of civil society".[4] Patricia Barnum describes it as a discussion about justice in the context of the "seemingly double standard" of the Old Testament concept of law (ius) and the New Testament charity (caritas).[4] The question posed by the author is whether God's laws may be harmonized with man's laws. Dives and Pauper starts the inquiry with the question of what the Christian scriptures teach about wealth (temporalia) and salvation.[4]

Genre

Written in Middle-English, Dives and Pauper is a long prose treatise which is structured as a dialogue between a wealthy layman and a spiritual poor man.[5] A lengthy piece of vernacular theology, the text is written as a treatise and exposition on the Ten Commandments.[6] Written in the early 15th century, Dives and Pauper can be classified as Middle English literature.

Engaging with Wycliffite theology, the writer uses the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments) as a framework to explore the relationship between the law of God (or Church law), as well as the laws of civil society in the 15th century.[4] As such, the text may also be classified as a 15th-century Christian text. The author uses the two interlocutors to engage with Wycliffite theology and explore whether or not Church law and the law of civil society can be harmonised.[4][5] The text begins with a prologue, Holy Poverty, which introduces the two characters central to the text and the relationship between the two interlocutors. Pauper, reflective of a friar, states that he observes the path of Christ-like perfection and chooses to live as a poor man, helping people spiritually in return for sustenance.[4] Dives, a member of the elite, asks Pauper to provide him moral instruction.[1] The text also copiously references the Vulgate Bible, which is a 4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.[4]

Manuscript

The author translated passages from the Vulgate, a Latin version of the Roman Catholic Bible, to English when citing the Bible meaning those who were illiterate in Latin were able to read Dives and Pauper.[6] There are fourteen manuscripts that contain Dives and Pauper as well as three printed editions which can be found from the 15th and 16th centuries.[5] In 1490, John Russhe, an English merchant, financed a first printing of six hundred copies, followed by a second printing in 1496.[4] The text begins with the Holy Poverty prologue and continues consecutively through each of the Ten Commandments.

Authorship

Although the author of Dives and Pauper has yet to be identified there is internal evidence to suggest the author was a Franciscan friar.[4][2] In 1548 John Bale initially attributed Dives and Pauper to Henry Parker, who was a Carmelite friar.[4] However, several authors and historians have since suggested that the author of Dives and Pauper was more likely a Franciscan friar.[2] There are several allusions within Dives and Pauper which suggest this. Early in Commandment I of Dives and Pauper, the author makes it clear that Pauper is set out for a path of ‘more perfection’ that leads him to criticise the secular clergy, for example, by mentioning the corrupt judges in the Ecclesiastical Courts.[4] P.H. Barnum suggests that the author's negative perspective of a secular clergy suggests that he was of the Franciscan order.[4] Furthermore, Franciscan friars are the only favourably discussed clerical group mentioned by the author and the only clerical group not to be criticised.[6] There is also continued mention of the life of St. Francis throughout Dives and Pauper such as in Percept Four as well as footwear mentioned by the author which seems to describe sandals traditionally worn by Franciscan Friars.[6][2] Further internal evidence in the author's other work, the Longleat sermons, also suggests the author was Franciscan.[5] However, Dickison also suggests that there is an indication that the author may not be from the Franciscan order due to the frequent translation of Bible passages into English which was not typical or expected of Franciscan friars.[6]

The writer is well-read in both theology and canon law, and it may therefore be speculated whether the writer had been trained in the Oxford convent.[2] This may be indicated by the author citing Thomas Docking's commentary on Deuteronomy, whose works were not available outside of Oxford until the later 15th century.[7]

Theology

The author of Dives and Pauper engages in numerous aspects of theology, including the use of images and icons in worship, the effectiveness of the Church hierarchy, issues of oaths and the paying of tithes.[8][4] The prologue, Holy Poverty, establishes the two interlocutors and their role in the text. Pauper is portrayed as a spiritually authoritative poor man whose lifestyle and choices are reflective of a friar.[5] Alternatively, Dives depicted a member of the elite and of wealth.[5] Pauper states that he follows the path of Christ-like perfection and in return for alms, he feeds people spiritually.[5][4] Alternatively, Dives asserts he, as an aristocrat, must follow the Ten Commandments to achieve salvation.[5]

The dialogue between the two interlocutors returns to the same theme of the nature of God.[4][2] In the Holy Poverty and Commandment I, the author illustrates his eagerness to overcome superstition and the dilemmas the Church faced to overcome a devotion to superstition.[9] The author implies that the vernacular concepts of God during the time of writing where helpless in overcoming sentiments and devotions to superstition. Instead, the author asserts that a broader and grander depiction of God as Prime Mover, a God who requires worship in spirit, would be able to overcome superstition.[10][4]

Date and historical setting

Date

Dives and Pauper is widely believed to have been written in England in the early 15th century.[2][4][1] There are two key historical allusions which suggest that the author began writing the text between 1402 and 1405.[4] The first reference is to comet in 1402 which was able to be seen by all of Europe.[4] This provides the reader with a terminus post quem for the date of initial composition.[4] The second piece of internal evidence is that the writer references that January fell on a Thursday in 1400 and "this year is come again on a Thursday," as it did in 1405, providing a terminus ante quem for Dives and Pauper.[4]

Heresy

In Commandment I the writer alludes to the troubles of England referring to the ‘comoun lawe’ the De heretico comburendo.[11] This law was passed in 1401 by the Parliament making heresy a capital crime in England.[4][11] The writer expresses protest against the De heretico comburendo which restricted preaching and the translating of the Latin Bible and scriptures for distribution.[4][11] Prior to 1407, the English translation of the Latin Bible was promoted to allow accessibility to the text.[11] In 1407, Archbishop Arundel enforced Constitutions which prohibited the translation of any scriptures into English, made it heretical to have possession of translated materials and limited unlicensed preaching.[4][11][10] The author of Dives and Pauper expresses that the Constitutions of Archbishop Arundel were enforced to restrict access to the vernacular Bible.[4] Dives and Pauper engaged in ideas reflecting Wycliffite ideology, including denouncing corruption in the clergy and supporting access to the English translations of the Bible.[4] As a result, under the De heretico comburendo and the Constitutions implemented by Archbishop Arundel, ownership of Dives and Pauper was declared heresy.[11] In 1430 an owner of Dives and Pauper, Robert Bert, was accused of heresy.[11]

References

- Connolly, Margaret (2007). "Dives and Pauper, Vol II". Medium Aevum. 76 (1): 164–165. ISSN 0025-8385. – via Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- PFANDER, H. G. (1 October 1933). "DIVES ET PAUPER". The Library. s4-XIV (3): 299–312. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XIV.3.299. ISSN 0024-2160.

- Rouse, Robert; Echard, Sian; Fulton, Helen; Rector, Geoff; Fay, Jacqueline Ann, eds. (2017). "Dives and Pauper". The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781118396957. ISBN 9781118396957.

- Barnum, Priscilla Heath (2004). Dives and pauper: (no. 323 in series). Introduction, explanatory notes and glossary. Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society. ISBN 978-0-19-722326-0.

- Crassons, Kate (3 August 2017), "Dives and Pauper", in Rouse, Robert; Echard, Sian; Fulton, Helen; Rector, Geoff (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain, Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9781118396957.wbemlb181, ISBN 978-1-118-39695-7, retrieved 17 May 2022

- B., Dickison, Roland (1950). Dives and Pauper : a study of a Fifteenth century homiletic tract. Univ of Florida. OCLC 500516322.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - John., Upland, Jack, editor. Heyworth, Peter, 1931– editor. Walsingham (1968). Jack Upland : Friar Daw's reply by John Walsingham ; and, Upland's rejoinder. Oxford University Press. OCLC 605993754.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Swanson, Robert (6 August 2019), "Pastoral care, pastoral cares, pastoral carers", Pastoral Care in Medieval England, 1 [edition]. | New York : Routledge, 2019.: Routledge, pp. 123–141, doi:10.4324/9781315599649-7, ISBN 9781315599649, S2CID 213023006, retrieved 31 May 2022

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Kathleen Kamerick (2008). "Shaping Superstition in Late Medieval England". Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft. 3 (1): 29–53. doi:10.1353/mrw.0.0093. ISSN 1940-5111. S2CID 161119235.

- Watson, Nicholas (October 1995). "Censorship and Cultural Change in Late-Medieval England: Vernacular Theology, the Oxford Translation Debate, and Arundel's Constitutions of 1409". Speculum. 70 (4): 822–864. doi:10.2307/2865345. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2865345. S2CID 162312580.

- HUDSON, ANNE; SPENCER, H. L. (1984). "Old Author, New Work: The Sermons of Ms Longleat". Medium Ævum. 53 (2): 220–238. doi:10.2307/43628828. ISSN 0025-8385. JSTOR 43628828.