Dinosaur classification

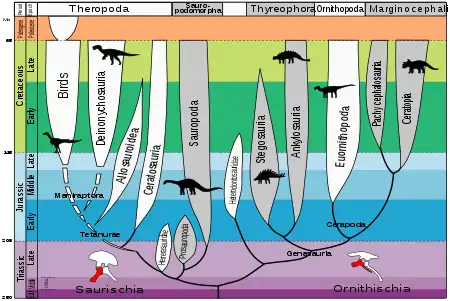

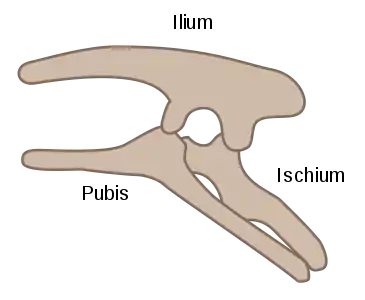

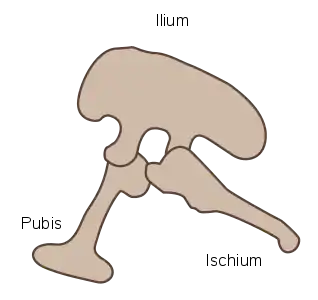

Dinosaur classification began in 1842 when Sir Richard Owen placed Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and Hylaeosaurus in "a distinct tribe or suborder of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria."[1] In 1887 and 1888 Harry Seeley divided dinosaurs into the two orders Saurischia and Ornithischia, based on their hip structure.[2] These divisions have proved remarkably enduring, even through several seismic changes in the taxonomy of dinosaurs.

The largest change was prompted by entomologist Willi Hennig's work in the 1950's, which evolved into modern cladistics. For specimens known only from fossils, the rigorous analysis of characters to determine evolutionary relationships between different groups of animals (clades) proved incredibly useful. When computer-based analysis using cladistics came into its own in the 1999s, paleontologists became among the first zoologists to almost wholeheartedly adopt the system.[3] Progressive scrutiny and work upon dinosaurian interrelationships, with the aid of new discoveries that have shed light on previously uncertain relationships between taxa, have begun to yield a stabilizing classification since the mid-2000s. While cladistics is the predominant classificatory system among paleontology professionals, the Linnean system is still in use, especially in works intended for popular distribution.

Benton classification

As most dinosaur paleontologists have advocated a shift away from traditional, ranked Linnaean taxonomy in favor of rankless phylogenetic systems,[3] few ranked taxonomies of dinosaurs have been published since the 1980s. The following schema is among the most recent, from the third edition of Vertebrate Palaeontology,[4] a respected undergraduate textbook. While it is structured so as to reflect evolutionary relationships (similar to a cladogram), it also retains the traditional ranks used in Linnaean taxonomy. The classification has been updated from the second edition in 2000 to reflect new research, but remains fundamentally conservative.

Michael Benton classifies all dinosaurs within the Series Amniota, Class Sauropsida, Subclass Diapsida, Infraclass Archosauromorpha, Division Archosauria, Subdivision Avemetatarsalia, Infradivision Ornithodira, and Superorder Dinosauria. Dinosauria is then divided into the two traditional orders, Saurischia and Ornithischia. The dagger (†) is used to indicate taxa with no living members.

Order Saurischia

- Suborder Theropoda

- †Infraorder Herrerasauria

- †Infraorder Coelophysoidea

- †Infraorder Ceratosauria+

- †Parvorder Neoceratosauria+

- †Superfamily Abelisauroidea

- †Family Abelisauridae

- †Family Noasauridae

- †Family Ceratosauridae

- †Superfamily Abelisauroidea

- †Parvorder Neoceratosauria+

- Infraorder Tetanurae

- †Superfamily Megalosauroidea

- †Family Megalosauridae

- †Family Spinosauridae

- †Parvorder Carnosauria

- †Superfamily Allosauroidea

- †Family Allosauridae

- †Family Carcharodontosauridae

- †Family Neovenatoridae

- †Family Metriacanthosauridae

- †Superfamily Allosauroidea

- Parvorder Coelurosauria

- †Family Coeluridae

- Division Maniraptoriformes

- †Family Tyrannosauridae

- †Family Ornithomimidae

- Subdivision Maniraptora

- †Family Alvarezsauridae

- †Family Therizinosauridae

- †Infradivision Deinonychosauria

- †Family Troodontidae

- †Family Dromaeosauridae

- Class Aves

- †Superfamily Megalosauroidea

- †Suborder Sauropodomorpha

- †Thecodontosaurus

- †Family Plateosauridae

- †Riojasaurus

- †Family Massospondylidae

- †Infraorder Sauropoda

- †Family Vulcanodontidae

- †Family Omeisauridae

- †Parvorder Neosauropoda

- †Family Cetiosauridae

- †Family Diplodocidae

- †Division Macronaria

- †Family Camarasauridae

- †Subdivision Titanosauriformes

- †Family Brachiosauridae

- †Infradivision Somphospondyli

- †Family Euhelopodidae

- †Family Titanosauridae

†Order Ornithischia

- †Family Pisanosauridae

- †Family Fabrosauridae

- †Suborder Thyreophora

- †Family Scelidosauridae

- †Infraorder Stegosauria

- †Infraorder Ankylosauria

- †Family Nodosauridae

- †Family Ankylosauridae

- †Suborder Cerapoda

- †Infraorder Pachycephalosauria

- †Infraorder Ceratopsia

- †Family Psittacosauridae

- †Family Protoceratopsidae

- †Family Ceratopsidae

- †Infraorder Ornithopoda

- †Family Heterodontosauridae

- †Family Hypsilophodontidae

- †Family Iguanodontidae *

- †Family Hadrosauridae

Weishampel/Dodson/Osmólska classification

The following is based on the second edition of The Dinosauria,[5] a compilation of articles by experts in the field that provided the most comprehensive coverage of Dinosauria available when it was first published in 1990. The second edition updates and revises that work.

The cladogram and phylogenetic definitions below reflect the current understanding of evolutionary relationships. The taxa and symbols in parentheses after a given taxa define these relationships. The plus symbol ("+") between taxa indicates the given taxa is a node-based clade, defined as comprising all descendants of the last common ancestor of the "added" taxa. The greater-than symbol (">") indicates the given taxon is a stem-based taxon, comprising all organisms sharing a common ancestor that is not also an ancestor of the "lesser" taxon.

Saurischia

- Herrerasauria (Herrerasaurus > Liliensternus, Plateosaurus)

- Herrerasauridae (Herrerasaurus + Staurikosaurus)

- ? Eoraptor lunensis

- Sauropodomorpha (Saltasaurus > Theropoda)

- ? Saturnalia tupiniquim

- ? Thecodontosauridae

- Prosauropoda (Plateosaurus > Sauropoda)

- ? Thecodontosauridae

- ? Anchisauria (Anchisaurus + Melanorosaurus)

- ? Anchisauridae (Anchisaurus > Melanorosaurus)

- ? Melanorosauridae (Melanorosaurus > Anchisaurus)

- Plateosauria (Jingshanosaurus + Plateosaurus)

- Massospondylidae

- Yunnanosauridae

- Plateosauridae (Plateosaurus > Yunnanosaurus, Massospondylus)

- Sauropoda (Saltasaurus > Plateosaurus)

- ? Anchisauridae

- ? Melanorosauridae

- Blikanasauridae

- Vulcanodontidae

- Eusauropoda (Shunosaurus + Saltasaurus)

- ? Euhelopodidae

- Mamenchisauridae

- Cetiosauridae (Cetiosaurus > Saltasaurus)

- Neosauropoda (Diplodocus + Saltasaurus)

- Diplodocoidea (Diplodocus > Saltasaurus)

- Rebbachisauridae (Rebbachisaurus > Diplodocus)

- Flagellicaudata

- Dicraeosauridae (Dicraeosaurus > Diplodocus)

- Diplodocidae (Diplodocus > Dicraeosaurus, Apatosaurus)

- Macronaria (Saltasaurus > Diplodocus)

- ? Jobaria tiguidensis

- Camarasauromorpha (Camarasaurus + Saltasaurus)

- Camarasauridae

- Titanosauriformes (Brachiosaurus + Saltasaurus)

- Brachiosauridae (Brachiosaurus > Saltasaurus)

- Titanosauria (Saltasaurus > Brachiosaurus)

- Andesauridae

- Lithostrotia (Malawisaurus + Saltasaurus)

- Isisaurus colberti

- Paralititan stromeri

- Nemegtosauridae

- Saltasauridae (Opisthocoelicaudia + Saltasaurus)

- Diplodocoidea (Diplodocus > Saltasaurus)

- Theropoda (Passer domesticus > Cetiosaurus oxoniensis)

- ? Eoraptor lunensis

- ? Herrerasauridae

- Ceratosauria (Ceratosaurus nasicornis > Aves)

- ? Coelophysoidea (Coelophysis > Ceratosaurus)

- ? Dilophosaurus wetherilli

- Coelophysidae (Coelophysis + Megapnosaurus)

- ? Neoceratosauria (Ceratosaurus > Coelophysis)

- Ceratosauridae

- Abelisauroidea (Carnotaurus sastrei > C. nasicornis)

- Abelisauria (Noasaurus + Carnotaurus)

- Noasauridae

- Abelisauridae (Abelisaurus comahuensis + C. sastrei)

- Carnotaurinae (Carnotaurus > Abelisaurus)

- Abelisaurinae (Abelisaurus > Carnotaurus)

- Abelisauria (Noasaurus + Carnotaurus)

- ? Coelophysoidea (Coelophysis > Ceratosaurus)

- Tetanurae (P. domesticus > C. nasicornis)

- ? Spinosauroidea (Spinosaurus aegyptiacus > P. domesticus)

- Megalosauridae (Megalosaurus bucklandii > P. domesticus, S. aegyptiacus, Allosaurus fragilis)

- Megalosaurinae (M. bucklandii > Eustreptospondylus oxoniensis)

- Eustreptospondylinae (E. oxoniensis > M. bucklandii)

- Spinosauridae (S. aegyptiacus > P. domesticus, M. bucklandii, A. fragilis)

- Baryonychinae (Baryonyx walkeri > S. aegyptiacus)

- Spinosaurinae (S. aegyptiacus > B. walkeri)

- Megalosauridae (Megalosaurus bucklandii > P. domesticus, S. aegyptiacus, Allosaurus fragilis)

- Avetheropoda (A. fragilis + P. domesticus)

- Carnosauria (A. fragilis > Aves)

- ? Spinosauroidea

- Monolophosaurus jiangi

- Allosauroidea (A. fragilis + Sinraptor dongi)

- Allosauridae (A. fragilis > S. dongi, Carcharodontosaurus saharicus)

- Sinraptoridae (S. dongi > A. fragilis, C. saharicus)

- Carcharodontosauridae (C. saharicus > A. fragilis, S. dongi)

- Coelurosauria (P. domesticus > A. fragilis)

- Compsognathidae (Compsognathus longipes > P. domesticus)

- Proceratosaurus bradleyi

- Ornitholestes hermanni

- Tyrannoraptora (Tyrannosaurus rex + P. domesticus)

- Coelurus fragilis

- Tyrannosauroidea (T. rex > Ornithomimus velox, Deinonychus antirrhopus, A. fragilis)

- Dryptosauridae

- Tyrannosauridae (T. rex + Tarbosaurus bataar + Daspletosaurus torosus + Albertosaurus sarcophagus + Gorgosaurus libratus)

- Tyrannosaurinae (T. rex > A. sarcophagus)

- Albertosaurinae (A. sarcophagus > T. rex)

- Maniraptoriformes (O. velox + P. domesticus)

- Ornithomimosauria (Gallimimus bullatus + Ornithomimus edmontonicus + Pelecanimimus polyodon)

- Maniraptora (P. domesticus > O. velox)

- Oviraptorosauria (Oviraptor philoceratops > P. domesticus)

- Caenagnathoidea (O. philoceratops + Caenagnathus collinsi)

- Caenagnathidae (C. collinsi > O. philoceratops)

- Oviraptoridae (O. philoceratops > C. collinsi)

- Oviraptorinae (O. philoceratops + Citipati osmolskae)

- Therizinosauroidea (Therizinosaurus + Beipiaosaurus)

- Caenagnathoidea (O. philoceratops + Caenagnathus collinsi)

- Paraves (P. domesticus > O. philoceratops)

- Eumaniraptora (P. domesticus + D. antirrhopus)

- Deinonychosauria (D. antirrhopus > P. domesticus or Dromaeosaurus albertensis + Troodon formosus)

- Troodontidae (T. formosus > Velociraptor mongoliensis)

- Dromaeosauridae (Microraptor zhaoianus + Sinornithosaurus millenii + V. mongoliensis)

- Avialae (Archaeopteryx + Neornithes)

- Deinonychosauria (D. antirrhopus > P. domesticus or Dromaeosaurus albertensis + Troodon formosus)

- Eumaniraptora (P. domesticus + D. antirrhopus)

- Oviraptorosauria (Oviraptor philoceratops > P. domesticus)

- Carnosauria (A. fragilis > Aves)

- ? Spinosauroidea (Spinosaurus aegyptiacus > P. domesticus)

Ornithischia

(Iguanodon/Triceratops > Cetiosaurus/Tyrannosaurus)

- ? Lesothosaurus diagnosticus

- ? Heterodontosauridae

- Genasauria (Ankylosaurus + Triceratops)

- Thyreophora (Ankylosaurus > Triceratops)

- Scelidosauridae

- Eurypoda (Ankylosaurus + Stegosaurus)

- Stegosauria (Stegosaurus > Ankylosaurus)

- Huayangosauridae (Huayangosaurus > Stegosaurus)

- Stegosauridae (Stegosaurus > Huayangosaurus)

- Dacentrurus armatus

- Stegosaurinae (Stegosaurus > Dacentrurus)

- Ankylosauria (Ankylosaurus > Stegosaurus)

- Ankylosauridae (Ankylosaurus > Panoplosaurus)

- Gastonia burgei

- Shamosaurus scutatus

- Ankylosaurinae (Ankylosaurus > Shamosaurus)

- Nodosauridae (Panoplosaurus > Ankylosaurus)

- Ankylosauridae (Ankylosaurus > Panoplosaurus)

- Stegosauria (Stegosaurus > Ankylosaurus)

- Cerapoda (Triceratops > Ankylosaurus)

- Ornithopoda (Edmontosaurus > Triceratops)

- ? Lesothosaurus diagnosticus

- ? Heterodontosauridae

- Euornithopoda

- Hypsilophodon foxii

- Thescelosaurus neglectus

- Iguanodontia (Edmontosaurus > Thescelosaurus)

- Tenontosaurus tilletti

- Rhabdodontidae

- Dryomorpha

- Dryosauridae

- Ankylopollexia

- Camptosauridae

- Styracosterna

- Lurdusaurus arenatus

- Iguanodontoidea (=Hadrosauriformes)

- Iguanodontidae

- Hadrosauridae (Telmatosaurus + Parasaurolophus + Corythosaurus)

- Telmatosaurus transsylvanicus

- Euhadrosauria

- Marginocephalia

- Pachycephalosauria (Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis > Triceratops horridus)

- Goyocephala (Goyocephale + Pachycephalosaurus)

- Homalocephaloidea (Homalocephale + Pachycephalosaurus)

- Goyocephala (Goyocephale + Pachycephalosaurus)

- Ceratopsia (Triceratops > Pachycephalosaurus)

- Pachycephalosauria (Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis > Triceratops horridus)

- Ornithopoda (Edmontosaurus > Triceratops)

- Thyreophora (Ankylosaurus > Triceratops)

Baron/Norman/Barrett classification

In 2017 Matthew G. Baron and his colleagues published a new analysis proposing to put Theropoda (except Herrerasauridae) and Ornithischia within a group called Ornithoscelida (a name originally coined by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1870), redefining Saurischia to cover Sauropodomorpha and Herrerasauridae. Amongst other things this would require hypercarnivory to have evolved independently for Theropoda and Herrerasauridae.[6][7] This scheme is currently debated among palaeontologists, with recent studies finding little difference between the traditional and newly proposed models.[8][9]

Cau 2018

In his paper about the stepwise evolution of the avian bauplan, Cau (2018) found in the parsimony analysis a polytomy between herrerasaur-grade taxa, Sauropodomorpha and the controversial Ornithoscelida. The Bayesian analysis, however, found weak support for the sister grouping of Dinosauria and Herrerasauria, but strong support for the dichotomy between Sauropodomorpha and Ornithoscelida, as shown below:[10]

| Dracohors |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Footnotes

- Owens, 1842.

- Seeley, 1888. While the paper was published in 1888, it was first delivered in 1887.

- Brochu, C.A.; Sumrall, C.D. (2001). "Phylogenetic nomenclature and paleontology" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 75 (4): 754–757. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2001)075<0754:PNAP>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85927950.

- Benton, Michael 2004. The classification scheme is available online Archived 2008-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Weishampel, 2004

- Baron MG; Norman DB; Barrett PM (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution" (PDF). Nature. 543 (7646): 501–506. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..501B. doi:10.1038/nature21700. PMID 28332513. S2CID 187506290.

- Naish, Darren (2017), "Ornithoscelida Rises: A New Family Tree for Dinosaurs", Scientific American Tetrapod Zoology blog, retrieved March 24, 2017

- Max C. Langer; Martín D. Ezcurra; Oliver W. M. Rauhut; Michael J. Benton; Fabien Knoll; Blair W. McPhee; Fernando E. Novas; Diego Pol; Stephen L. Brusatte (2017). "Untangling the dinosaur family tree" (PDF). Nature. 551 (7678): E1–E3. Bibcode:2017Natur.551E...1L. doi:10.1038/nature24011. hdl:1983/d088dae2-c7fa-4d41-9fa2-aeebbfcd2fa3. PMID 29094688. S2CID 205260354.

- Matthew G. Baron; David B. Norman; Paul M. Barrett (2017). "Baron et al. reply". Nature. 551 (7678): E4–E5. Bibcode:2017Natur.551E...4B. doi:10.1038/nature24012. PMID 29094705. S2CID 205260360.

- Andrea Cau (2018). "The assembly of the avian body plan: a 160-million-year long process". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 57 (1): 1–25. doi:10.4435/BSPI.2018.01.

References

- Benton, Michael J. (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology, Third Edition. Blackwell Publishing. p. 472 pp. ISBN 9780632056378.

- Owen, Richard (1842). "Report on British Fossil Reptiles: Part II". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 11: 60–204.

- Seeley, Harry Govier (1888). "On the classification of the Fossil Animals commonly named Dinosauria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 43 (258–265): 165–171. Bibcode:1887RSPS...43..165S. doi:10.1098/rspl.1887.0117..

- Weishampel, David B. (2004). Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press. p. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.