Differential diagnoses of depression

Depression, one of the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric disorders,[2][3] is being diagnosed in increasing numbers in various segments of the population worldwide.[4][5] Depression in the United States alone affects 17.6 million Americans each year or 1 in 6 people. Depressed patients are at increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and suicide. Within the next twenty years depression is expected to become the second leading cause of disability worldwide and the leading cause in high-income nations, including the United States. In approximately 75% of suicides, the individuals had seen a physician within the prior year before their death, 45–66% within the prior month. About a third of those who died by suicide had contact with mental health services in the prior year, a fifth within the preceding month.[6][7][8][9][10]

There are many psychiatric and medical conditions that may mimic some or all of the symptoms of depression or may occur comorbid to it.[11][12][13] A disorder either psychiatric or medical that shares symptoms and characteristics of another disorder, and may be the true cause of the presenting symptoms is known as a differential diagnosis.[14]

Many psychiatric disorders such as depression are diagnosed by allied health professionals with little or no medical training,[15] and are made on the basis of presenting symptoms without proper consideration of the underlying cause, adequate screening of differential diagnoses is often not conducted.[16][17][18][19][20][21] According to one study, "non-medical mental health care providers may be at increased risk of not recognizing masked medical illnesses in their patients."[22]

Misdiagnosis or missed diagnoses may lead to lack of treatment or ineffective and potentially harmful treatment which may worsen the underlying causative disorder.[23][24] A conservative estimate is that 10% of all psychological symptoms may be due to medical reasons,[25] with the results of one study suggesting that about half of individuals with a serious mental illness "have general medical conditions that are largely undiagnosed and untreated and may cause or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms".[26][27]

In a case of misdiagnosed depression recounted in Newsweek, a writer received treatment for depression for years; during the last 10 years of her depression the symptoms worsened, resulting in multiple suicide attempts and psychiatric hospitalizations. When an MRI finally was performed, it showed the presence of a tumor. However, she was told by a neurologist that it was benign. After a worsening of symptoms, and upon the second opinion of another neurologist, the tumor was removed. After the surgery, she no longer had depressive symptoms.[28]

Autoimmune disorders

- Celiac disease; is an autoimmune disorder in which the body is unable to digest gluten which is found in various food grains, most notably wheat, and also rye and barley. Current research has shown its neuropsychiatric symptoms may manifest without the gastrointestinal symptoms.

- "However, more recent studies have emphasized that a wider spectrum of neurologic syndromes may be the presenting extraintestinal manifestation of gluten sensitivity with or without intestinal pathology."[29]

- Lupus: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is a chronic autoimmune connective tissue disease that can affect any part of the body.[30] Lupus can cause or worsen depression.[31]

Bacterial-viral-parasitic infection

- Lyme disease; is a bacterial infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochete bacterium transmitted by the Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). Lyme disease is one of a group of diseases which have earned the name the "great imitator" for their propensity to mimic the symptoms of a wide variety of medical and neuropsychiatric disorders.[32][33] Lyme disease is an underdiagnosed illness, partially as a result of the complexity and unreliability of serologic testing.[34]

- "Because of the rapid rise of Lyme borreliosis nationwide and the need for antibiotic treatment to prevent severe neurologic damage, mental health professionals need to be aware of its possible psychiatric presentations.[35]

- Syphilis; the prevalence of which is on the rise, is another of the "great imitators", which if left untreated can progress to neurosyphilis and affect the brain, can present with solely neuropsychiatric symptoms. "This case emphasises that neurosyphilis still has to be considered in the differential diagnosis within the context of psychiatric conditions and diseases. Owing to current epidemiological data and difficulties in diagnosing syphilis, routine screening tests in the psychiatric field are necessary."[36]

- Neurocysticercosis (NCC): is an infection of the brain or spinal cord caused by the larval stage of the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium. NCC is the most common helminthic (parasitic worm) infestation of the central nervous system worldwide. Humans develop cysticercosis when they ingest eggs of the pork tapeworm via contact with contaminated fecal matter or eating infected vegetables or undercooked pork.[37] "While cysticercosis is endemic in Latin America, it is an emerging disease with increased prevalence in the United States."[38] "The rate of depression in those with neurocysticercosis is higher than in the general population."[39]

- Toxoplasmosis; is an infection caused by Toxoplasma gondii an intracellular protozoan parasite. Humans can be infected in 3 different ways: ingestion of tissue cysts, ingestion of oocysts, or in utero infection with tachyzoites. One of the prime methods for transmission to humans is contact with the feces of the host species, the domesticated cat.[40] Toxoplasma gondii infects approximately 30% of the world's human population, but causes overt clinical symptoms in only a small segment of those infected. Exposure to Toxoplasma gondii (seropositivity) without developing Toxoplasmosis has been proven to alter various characteristics of human behavior as well as being a causative factor in some cases of depression,[41][42] in addition, studies have linked seropositivity with an increased rate of suicide[43]

- West Nile virus (WNV); which can cause encephalitis has been reported to be a causal factor in developing depression in 31% of those infected in a study conducted in Houston, Texas and reported to the Center for Disease Control (CDC). The primary vectors for disease transmission to humans are various species of mosquito.[44][45] WNV which is endemic to Southern Europe, Africa the Middle East and Asia[46] was first identified in the United States in 1999. Between 1999 and 2006, 20,000 cases of confirmed symptomatic WNV were reported in the United States, with estimates of up to 1 million being infected. "WNV is now the most common cause of epidemic viral encephalitis in the United States, and it will likely remain an important cause of neurological disease for the foreseeable future."[47]

Blood disorders

- Anemia: is a decrease in normal number of red blood cells (RBCs) or less than the normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood.[48] Depressive symptoms are associated with anemia in a general population of older persons living in the community.[49]

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Between 1 and 4 million Americans are believed to have chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), yet only 50% have consulted a physician for symptoms of CFS. In addition individuals with CFS symptoms often have an undiagnosed medical or psychiatric disorder such as diabetes, thyroid disease or substance abuse. CFS, at one time considered to be psychosomatic in nature, is now considered to be a valid medical condition in which early diagnosis and treatment can aid in alleviating or completely resolving symptoms.[50] While frequently misdiagnosed as depression,[51] differences have been noted in rate of cerebral blood flow.[52]

CFS is underdiagnosed in more than 80% of the people who have it; at the same time, it is often misdiagnosed as depression.[53]

Dietary disorders

- Fructose malabsorption and lactose intolerance; deficient fructose transport by the duodenum, or by the deficiency of the enzyme, lactase in the mucosal lining, respectively. As a result of this malabsorption the saccharides reach the colon and are digested by bacteria which convert them to short chain fatty acids, CO

2, and H2. Approximately 50% of those affected exhibit the physical signs of irritable bowel syndrome.[54]

- "Fructose malabsorption may play a role in the development of depressed mood. Fructose malabsorption should be considered in patients with symptoms of major depression...."[55]

Endocrine system disorders

Dysregulation of the endocrine system may present with various neuropsychiatric symptoms; irregularities in the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal (HPA) axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis have been shown in patients with primary depression.[57]

| HPT and HPA axes abnormalities observed in patients with depression (Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB. 1996) | ||||

|

HPT axes irregularities:

HPA axes irregularities:

|

Adrenal gland

- Addison's disease: also known as chronic adrenal insufficiency, hypocortisolism, and hypocorticism) is a rare endocrine disorder wherein the adrenal glands, located above the kidneys, produce insufficient steroid hormones (glucocorticoids and often mineralocorticoids). "Addison's disease presenting with psychiatric features in the early stage has the tendency to be overlooked and misdiagnosed."[58]

- Cushing's Syndrome, also known as hypercortisolism, is an endocrine disorder characterized by an excess of cortisol. In the absence of prescribed steroid medications, it is caused by a tumor on the pituitary or adrenal glands, or more rarely, an ectopic hormone-secreting tumor. Depression is a common feature in diagnosed patients and it often improves with treatment.[59]

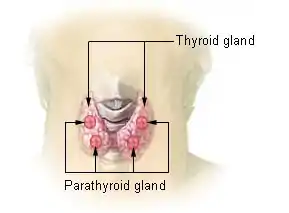

Thyroid and parathyroid glands

- Graves' disease: an autoimmune disease where the thyroid is overactive, resulting in hyperthyroidism and thyrotoxicosis.

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis: also known chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease in which the thyroid gland is gradually destroyed by a variety of cell and antibody mediated immune processes. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is associated with thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin autoantibodies[60]

- Hashitoxicosis

- Hypothyroidism

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypoparathyroidism; can affect calcium homeostasis, supplementation of which has completely resolved cases of depression in which hypoparathyroidism is the sole causative factor.[61]

Pituitary tumors

Tumors of the pituitary gland are fairly common in the general population with estimates ranging as high as 25%.[62] Most tumors are considered to be benign and are often an incidental finding discovered during autopsy or as of neuroimaging in which case they are dubbed "incidentalomas". Even in benign cases, pituitary tumors can affect cognitive, behavioral and emotional changes.[63][64] Pituitary microadenomas are smaller than 10 mm in diameter and are generally considered benign, yet the presence of a microadenoma has been positively identified as a risk factor for suicide.[65][66]

"... patients with pituitary disease were diagnosed and treated for depression and showed little response to the treatment for depression".[67]

Pancreas

- Hypoglycemia: an overproduction of insulin causes reduced blood levels of glucose. In one study of patients recovering from acute lung injury in intensive care, those patients who developed hypoglycemia while hospitalized showed an increased rate of depression.[68]

Neurological

CNS Tumors

In addition to pituitary tumors, tumors in various locations in the central nervous system may cause depressive symptoms and be misdiagnosed as depression.[28][69]

Post concussion syndrome

Post-concussion syndrome (PCS), is a set of symptoms that a person may experience for weeks, months, or occasionally years after a concussion with a prevalence rate of 38–80% in mild traumatic brain injuries, it may also occur in moderate and severe cases of traumatic brain injury.[70] A diagnosis may be made when symptoms resulting from concussion, depending on criteria, last for more than three to six months after the injury, in which case it is termed persistent postconcussive syndrome (PPCS).[71][72][73][74][75] In a study of the prevalence of post concussion syndrome symptoms in patients with depression utilizing the British Columbia Postconcussion Symptom Inventory: "Approximately 9 out of 10 patients with depression met liberal self-report criteria for a postconcussion syndrome and more than 5 out of 10 met conservative criteria for the diagnosis." These self reported rates were significantly higher than those obtained in a scheduled clinical interview. Normal controls have exhibited symptoms of PCS as well as those seeking psychological services. There is considerable debate over the diagnosis of PCS in part because of the medico-legal and thus monetary ramifications of receiving the diagnosis.[76]

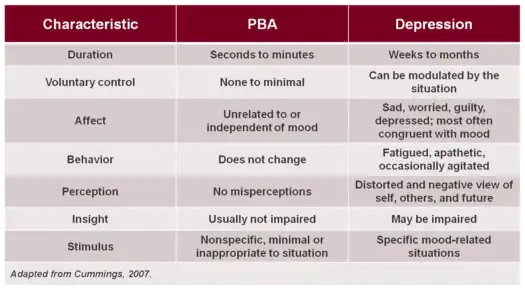

Pseudobulbar affect

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is an affective disinhibition syndrome that is largely unrecognized in clinical settings and thus often untreated due to ignorance of the clinical manifestations of the disorder; it may be misdiagnosed as depression.[77] It often occurs secondary to various neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and also can result from head trauma. PBA is characterized by involuntary and inappropriate outbursts of laughter and/or crying. PBA has a high prevalence rate with estimates of 1.5–2 million cases in the United States alone.[78]

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic demyelinating disease in which the myelin sheaths of cells in the brain and spinal cord are irreparably damaged. Symptoms of depression are very common in patients at all stages of the disease and may be exacerbated by medical treatments, notably interferon beta-1a.[79]

Neurotoxicity

Various compounds have been shown to have neurotoxic effects many of which have been implicated as having a causal relationship in the development of depression.

Cigarette smoking

There has been research which suggests a correlation between cigarette smoking and depression. The results of one recent study suggest that smoking cigarettes may have a direct causal effect on the development of depression.[80] There have been various studies done showing a positive link between smoking, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.[81][82]

In a study conducted among nurses, those smoking between 1-24 cigarettes per day had twice the suicide risk; 25 cigarettes or more, 4 times the suicide risk, than those who had never smoked.[83][84] In a study of 300,000 male U.S. Army soldiers, a definitive link between suicide and smoking was observed with those smoking over a pack a day having twice the suicide rate of non-smokers.[85]

"Current daily smoking, but not past smoking, predicted the subsequent occurrence of suicidal thoughts or attempt."[86]

"It would seem unwise, nevertheless, to rule out the possibility that smoking might be among the antecedent factors associated with the development of depression."[87]

"Abstinence from cigarettes for prolonged periods may be associated with a decrease in depressive symptomatology."[88]

"The stress induction model of smoking suggests, however, that smoking causes stress and concomitant negative affect."[89]

Medication

Various medications have been suspected of having a causal relation in the development of depression; this has been classified as "organic mood syndrome". Some classes of medication such as those used to treat hypertension, have been recognized for decades as having a definitive relationship with the development of depression.[90]

Monitoring of those taking medications which have shown a relationship with depression is often indicated, as well as the necessity of factoring in the use of such medications in the diagnostic process.[91]

- Topical Tretinoin (Retin-A); derived from Vitamin A and used for various medical conditions such as in topical solutions used to treat acne vulgaris. Although applied externally to the skin, it may enter the bloodstream and cross the blood brain barrier where it may have neurotoxic effects.[92]

- Interferons; proteins produced by the human body, three types have been identified alpha, beta and gamma. Synthetic versions are utilized in various medications used to treat different medical conditions such as the use of interferon-alpha in cancer treatment and hepatitis C treatment. All three classes of interferons may cause depression and suicidal ideation.[93]

Chronic exposure to organophosphates

The neuropsychiatric effects of chronic organophosphate exposure include mood disorders, suicidal thinking and behaviour, cognitive impairment and chronic fatigue.[94]

Neuropsychiatric

Bipolar disorder

- Bipolar disorder is frequently misdiagnosed as major depression, and is thus treated with antidepressants alone which is not only not efficacious it is often contraindicated as it may exacerbate hypomania, mania, or cycling between moods.[95][96] There is ongoing debate about whether this should be classified as a separate disorder because individuals diagnosed with major depression often experience some hypomanic symptoms, indicating a continuum between the two.[97]

Nutritional deficiencies

Nutrition plays a key role in every facet of maintaining proper physical and psychological wellbeing. Insufficient or inadequate nutrition can have a profound effect on mental health. The emerging field of nutritional neuroscience explores the various connections between diet, neurological functioning and mental health.

- Vitamin B6: pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), the active form of B6, is a cofactor in the dopamine serotonin pathway, a deficiency in vitamin B6 may cause depressive symptoms.[98]

- Folate (vitamin B9) – Vitamin B12 cobalamin: Low blood plasma and particularly red cell folate and diminished levels of vitamin B12 have been found in patients with depressive disorders. "[W]e suggest that oral doses of both folic acid (800 μg/(mcg) daily) and vitamin B12 (1 mg daily) should be tried to improve treatment outcome in depression."[99][100]

- Long chain fatty acids: higher levels of omega-6 and lower levels of omega-3 fatty acids has been associated with depression and behavioral change.[101][102][103]

- Vitamin D deficiency is associated with depression

Sleep disorders

- Insomnia: While the inability to fall asleep is often a symptom of depression, it can also in some instances serve as the trigger for developing a depressive disorder.[104][105] It can be transient, acute or chronic. It can be a primary disorder or a co-morbid one.

- Restless legs syndrome (RLS), also known as Wittmaack-Ekbom's syndrome, is characterized by an irresistible urge to move one's body to stop uncomfortable or odd sensations. It most commonly affects the legs, but can also affect the arms or torso, and even phantom limbs.[106] Restless Leg syndrome has been associated with Major depressive disorder. "Adjusted odds ratio for diagnosis of major depressive disorder... suggested a strong association between restless legs syndrome and major depressive disorder and/or panic disorder."[107]

- Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder characterized by pauses in breathing during sleep. Each episode, called an apnea, lasts long enough for one or more breaths to be missed; such episodes occur repeatedly throughout the sleep cycle. Undiagnosed sleep apnea may cause or contribute to the severity of depression.[108]

- Circadian rhythm sleep disorders, of which few clinicians are aware, often go untreated or are treated inappropriately, as when misdiagnosed as either primary insomnia or as a psychiatric condition.[109]

References

- Neuroimaging: a new training issue in psychiatry? -- Bhriain et al. 2005 - Archived 2010-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Sharp LK, Lipsky MS (September 2002). "Screening for depression across the lifespan: a review of measures for use in primary care settings". American Family Physician. 66 (6): 1001–8. PMID 12358212.

- Torzsa P, Szeifert L, Dunai K, Kalabay L, Novák M (September 2009). "A depresszió diagnosztikája és kezelése a családorvosi gyakorlatban". Orvosi Hetilap. 150 (36): 1684–93. doi:10.1556/OH.2009.28675. PMID 19709983.

- College Students Exhibiting More Severe Mental Illness, Study Finds

- Lambert KG (2006). "Rising rates of depression in today's society: Consideration of the roles of effort-based rewards and enhanced resilience in day-to-day functioning". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 30 (4): 497–510. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.09.002. PMID 16253328. S2CID 12525915.

- Depression and Suicide Andrew B. Medscape

- González HM; Vega WA; Williams DR; Tarraf W; West BT; Neighbors HW (January 2010). "Depression Care in the United States: Too Little for Too Few". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. PMC 2887749. PMID 20048221.

- Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL (June 2002). "Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (6): 909–16. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. PMC 5072576. PMID 12042175.

- Lee HC, Lin HC, Liu TC, Lin SY (June 2008). "Contact of mental and nonmental health care providers prior to suicide in Taiwan: a population-based study". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 53 (6): 377–83. doi:10.1177/070674370805300607. PMID 18616858.

- Pirkis J, Burgess P (December 1998). "Suicide and recency of health care contacts. A systematic review". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 173 (6): 462–74. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.6.462. PMID 9926074. S2CID 43144463.

- Adults Admitted to a Mood-Disorder Clinic Are Often Misdiagnosed by Marlene Busko

- Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, Fisher WH, Hargreaves WA, Harding CM (November 2004). "Prevalence, Severity, and Co-occurrence of Chronic Physical Health Problems of Persons with Serious Mental Illness". Psychiatric Services. 55 (11): 1250–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250. PMC 2759895. PMID 15534013.

- Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D (December 1996). "Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review". Psychiatric Services. 47 (12): 1356–63. doi:10.1176/ps.47.12.1356. PMID 9117475.

- Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- differential diagnosis definition: the distinguishing of a disease or condition from others presenting similar symptoms

- Preventing Misdiagnosis of Women: A Guide to Physical Disorders That Have Psychiatric Symptoms (Women's Mental Health and Development) by Dr. Elizabeth Adele Klonoff and Dr. Hope Landrine p. xxi Publisher: Sage Publications, Inc; 1 edition (1997) Language: English ISBN 0761900470

- Singh H, Thomas EJ, Wilson L, et al. (July 2010). "Errors of Diagnosis in Pediatric Practice: A Multisite Survey". Pediatrics. 126 (1): 70–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3218. PMC 2921702. PMID 20566604.

- Margolis RL (1994). "Nonpsychiatrist house staff frequently misdiagnose psychiatric disorders in general hospital inpatients". Psychosomatics. 35 (5): 485–91. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(94)71743-6. PMID 7972664.

- Clinical errors and medical negligence Femi Oyebode; Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (2006) 12: 221-227 The Royal College of Psychiatrists

- Scheinbaum BW (1979). "Psychiatric diagnostic error". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 5 (4): 560–3. doi:10.1093/schbul/5.4.560. PMID 515705.

- Hall RC, Popkin MK, Devaul RA, Faillace LA, Stickney SK (November 1978). "Physical illness presenting as psychiatric disease". Archives of General Psychiatry. 35 (11): 1315–20. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770350041003. PMID 568461.

- Small GW (December 2009). "Differential Diagnoses and Assessment of Depression in Elderly Patients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 70 (12): e47. doi:10.4088/JCP.8001tx20c. PMID 20141704.

- Grace GD, Christensen RC (2007). "Recognizing psychologically masked illnesses: the need for collaborative relationships in mental health care". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 9 (6): 433–6. doi:10.4088/pcc.v09n0605. PMC 2139921. PMID 18185822.

- Witztum E, Margolin J, Bar-On R, Levy A (1995). "Stigma, labelling and psychiatric misdiagnosis: origins and outcomes". Medicine and Law. 14 (7–8): 659–69. PMID 8668014.

- Margolin J, Witztum E, Levy A (June 1995). "Consequences of misdiagnosis and labeling in psychiatry". Harefuah. 128 (12): 763–7, 823. PMID 7557684.

- When Psychological Problems Mask Medical Disorders: A Guide for Psychotherapists. Morrison J: New York, Guilford, 1997 ISBN 1-57230-539-8

- Previously undetected metabolic syndromes and infectious diseases among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services Rothbard AB,et al: 60:534–537,2009

- Hall RC, Gardner ER, Stickney SK, LeCann AF, Popkin MK (September 1980). "Physical illness manifesting as psychiatric disease. II. Analysis of a state hospital inpatient population". Archives of General Psychiatry. 37 (9): 989–95. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220027002. PMID 7416911.

- Is It Depression--or a Tumor? - Newsweek Nov 21, 2007

- Bushara KO (April 2005). "Neurologic presentation of celiac disease". Gastroenterology. 128 (4 Suppl 1): S92–7. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.018. PMID 15825133.

- James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- Lupus Disease Activity May Cause, Worsen Depression — Psychiatric Newsby J Arehart-Trechel - 2006 Archived March 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Fallon BA, Nields JA (November 1994). "Lyme disease: a neuropsychiatric illness". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 151 (11): 1571–83. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.11.1571. PMID 7943444. S2CID 22568915.

- Hájek T, Pasková B, Janovská D, et al. (February 2002). "Higher prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in psychiatric patients than in healthy subjects". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (2): 297–301. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.297. PMID 11823274.

- Fallon BA, Kochevar JM, Gaito A, Nields JA (September 1998). "The underdiagnosis of neuropsychiatric Lyme disease in children and adults". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 21 (3): 693–703, viii. doi:10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70032-0. PMID 9774805.

- Fallon BA, Nields JA, Parsons B, Liebowitz MR, Klein DF (July 1993). "Psychiatric manifestations of Lyme borreliosis". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 54 (7): 263–8. PMID 8335653.

- Friedrich F, Geusau A, Greisenegger S, Ossege M, Aigner M (2009). "Manifest psychosis in neurosyphilis". General Hospital Psychiatry. 31 (4): 379–81. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.09.010. PMID 19555800.

- García HH, Evans CA, Nash TE, et al. (October 2002). "Current consensus guidelines for treatment of neurocysticercosis". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15 (4): 747–56. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.4.747-756.2002. PMC 126865. PMID 12364377.

- Sorvillo FJ, DeGiorgio C, Waterman SH (February 2007). "Deaths from cysticercosis, United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (2): 230–5. doi:10.3201/eid1302.060527. PMC 2725874. PMID 17479884.

- Almeida SM, Gurjão SA (February 2010). "Frequency of depression among patients with neurocysticercosis". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 68 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2010000100017. PMID 20339658.

- Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y (May 2007). "Effects of Toxoplasma gondii Infection on the Brain". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 33 (3): 745–51. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm008. PMC 2526127. PMID 17322557.

- Henriquez SA, Brett R, Alexander J, Pratt J, Roberts CW (2009). "Neuropsychiatric Disease and Toxoplasma gondii Infection". Neuroimmunomodulation. 16 (2): 122–33. doi:10.1159/000180267. PMID 19212132. S2CID 7382051.

- Nilamadhab Karl; Baikunthanath Misra (February 2004). "Toxoplasma gondii serpositivity and depression: a case report". BMC Psychiatry. 4 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-1. PMC 356918. PMID 15018628.

- Yagmur, F; Yazar, S; Temel, HO; Cavusoglu, M (2010). "May Toxoplasma gondii increase suicide attempt-preliminary results in Turkish subjects?". Forensic Science International. 199 (1–3): 15–7. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.02.020. PMID 20219300.

- Depression after infection with West Nile virus Murray KO, Resnick M, Miller V. Depression after infection with West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2007 Mar [Retrieved July 9, 2010]. Available from

- Berg PJ, Smallfield S, Svien L (April 2010). "An investigation of depression and fatigue post West Nile virus infection". South Dakota Medicine. 63 (4): 127–9, 131–3. PMID 20397375.

- Zeller HG, Schuffenecker I (March 2004). "West Nile Virus: An Overview of Its Spread in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin in Contrast to Its Spread in the Americas". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 23 (3): 147–56. doi:10.1007/s10096-003-1085-1. PMID 14986160. S2CID 24372103.

- Carson PJ, Konewko P, Wold KS, et al. (September 2006). "Long‐Term Clinical and Neuropsychological Outcomes of West Nile Virus Infection". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (6): 723–30. doi:10.1086/506939. PMID 16912946. S2CID 2765866.

- MedicineNet.com Definition of Anemia

- Onder G, Penninx BW, Cesari M, et al. (September 2005). "Anemia is associated with depression in older adults: results from the InCHIANTI study". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 60 (9): 1168–72. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.9.1168. PMID 16183958.

- CDC - Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Jul 1, 2010 ... CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

- Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA (2008). "A Systematic Review of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Don't Assume It's Depression". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 10 (2): 120–8. doi:10.4088/pcc.v10n0206. PMC 2292451. PMID 18458765.

- MacHale SM, Lawŕie SM, Cavanagh JT, et al. (June 2000). "Cerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depression". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 176 (6): 550–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.6.550. PMID 10974961.

- Griffith JP, Zarrouf FA.,2008

- Ledochowski M, Widner B, Sperner-Unterweger B, Propst T, Vogel W, Fuchs D (July 2000). "Carbohydrate malabsorption syndromes and early signs of mental depression in females". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 45 (7): 1255–9. doi:10.1023/A:1005527230346. PMID 10961700. S2CID 25720361.

- Ledochowski M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Widner B, Fuchs D (June 1998). "Fructose malabsorption is associated with early signs of mental depression". European Journal of Medical Research. 3 (6): 295–8. PMID 9620891.

- Ledochowski M, Widner B, Bair H, Probst T, Fuchs D (October 2000). "Fructose- and Sorbitol-reduced Diet Improves Mood and Gastrointestinal Disturbances in Fructose Malabsorbers". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 35 (10): 1048–52. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.491.1764. doi:10.1080/003655200451162. PMID 11099057. S2CID 218909742.

- Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB (June 1996). "Depression and endocrine disorders: focus on the thyroid and adrenal system". The British Journal of Psychiatry. Supplement. 168 (30): 123–8. doi:10.1192/S0007125000298504. PMID 8864158. S2CID 38909762.

- Iwata M, Hazama GI, Shirayama Y, Ueta T, Yoshioka S, Kawahara R (2004). "A case of Addison's disease presented with depression as a first symptom". Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi = Psychiatria et Neurologia Japonica. 106 (9): 1110–6. PMID 15580869.

- Sonino, N (2001). "Psychiatric disorders associated with Cushing's syndrome. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment". CNS Drugs. 15 (1172–7047): 361–73. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115050-00003. PMID 11475942. S2CID 34438879.

- McLachlan SM, Nagayama Y, Pichurin PN, et al. (December 2007). "The Link between Graves' Disease and Hashimoto's Thyroiditis: A Role for Regulatory T Cells". Endocrinology. 148 (12): 5724–33. doi:10.1210/en.2007-1024. PMID 17823263.

- Bohrer T, Krannich JH (2007). "Depression as a manifestation of latent chronic hypoparathyroidism". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 8 (1): 56–9. doi:10.1080/15622970600995146. PMID 17366354. S2CID 23319026.

- Pituitary Macroadenomas eMedicine

- Meyers CA (1998). "Neurobehavioral functioning of adults with pituitary disease". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 67 (3): 168–72. doi:10.1159/000012277. PMID 9667064. S2CID 46806241.

- Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, et al. (August 2004). "The prevalence of pituitary adenomas". Cancer. 101 (3): 613–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.20412. PMID 15274075. S2CID 16595581.

- Alicja Furgal-Borzycha; et al. (October 2007). "Increased Incidence of Pituitary Microadenomas in Suicide Victims". Neuropsychobiology. 55 (3–4): 163–166. doi:10.1159/000106475. PMID 17657169. S2CID 34408650.

- Forensic Neuropathology p. 137 By Jan E. Leestma

- Weitzner MA, Kanfer S, Booth-Jones M (2005). "Apathy and Pituitary Disease: It Has Nothing to Do With Depression". Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 17 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.2.159. PMID 15939968.

- Dowdy DW, Dinglas V, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. (October 2008). "Intensive care unit hypoglycemia predicts depression during early recovery from acute lung injury*". Critical Care Medicine. 36 (10): 2726–33. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818781f5. PMC 2605796. PMID 18766087.

- Lahmeyer HW (June 1982). "Frontal lobe meningioma and depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 43 (6): 254–5. PMID 7085582.

- Rao V, Lyketsos C (2000). "Neuropsychiatric sequelae of traumatic brain injury". Psychosomatics. 41 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.41.2.95. PMID 10749946. S2CID 6717589.

- McHugh T, Laforce R, Gallagher P, Quinn S, Diggle P, Buchanan L (2006). "Natural history of the long-term cognitive, affective, and physical sequelae of mild traumatic brain injury". Brain and Cognition. 60 (2): 209–211. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2004.09.018. PMID 16646125. S2CID 53190838.

- Legome E. 2006. Postconcussive syndrome. eMedicine.com. Accessed January 1, 2007.

- Schnadower D, Vazquez H, Lee J, Dayan P, Roskind CG (2007). "Controversies in the evaluation and management of minor blunt head trauma in children". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 19 (3): 258–264. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e3281084e85. PMID 17505183. S2CID 20231463.

- Bigler ED (2008). "Neuropsychology and clinical neuroscience of persistent post-concussive syndrome". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 14 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/S135561770808017X. PMID 18078527.

- Evans RW (2004). "Post-traumatic headaches". Neurologic Clinics. 22 (1): 237–249. doi:10.1016/S0733-8619(03)00097-5. PMID 15062537. S2CID 18249136.

- Iverson GL (May 2006). "Misdiagnosis of the persistent postconcussion syndrome in patients with depression". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 21 (4): 303–10. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2005.12.008. PMID 16797916.

- Archiniegas DB, Lauterbach EC, Anderson KE, Chow TW, et al. (2005). "The differential diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect (PBA). Distinguishing PBA among disorders of mood and affect. Proceedings of a roundtable meeting". CNS Spectr. 10 (5): 1–16. doi:10.1017/S1092852900026602. PMID 15962457. S2CID 45811704.

- Moore SR, Gresham LS, Bromberg MB, Kasarkis EJ, Smith RA (1997). "A self report measure of affective lability". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 63 (1): 89–93. doi:10.1136/jnnp.63.1.89. PMC 2169647. PMID 9221973.

- R J Siegert; D A Abernethy (2004). "Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 76 (4): 469–475. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.054635. PMC 1739575. PMID 15774430.

- Smoking Linked to Increased Depression Risk / Medscape

- Iwasaki M, Akechi T, Uchitomi Y, Tsugane S (April 2005). "Cigarette Smoking and Completed Suicide among Middle-aged Men: A Population-based Cohort Study in Japan". Annals of Epidemiology. 15 (4): 286–92. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.08.011. PMID 15780776.

- Miller M, Hemenway D, Rimm E (May 2000). "Cigarettes and suicide: a prospective study of 50,000 men". American Journal of Public Health. 90 (5): 768–73. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.5.768. PMC 1446219. PMID 10800427.

- Hemenway D, Solnick SJ, Colditz GA (February 1993). "Smoking and suicide among nurses". American Journal of Public Health. 83 (2): 249–51. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.2.249. PMC 1694571. PMID 8427332.

- Thomas Bronischa; Michael Höflerab; Roselind Liebac (May 2008). "Smoking predicts suicidality: Findings from a prospective community study". Journal of Affective Disorders. 108 (1): 135–145. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.010. PMID 18023879.

- Miller M, Hemenway D, Bell NS, Yore MM, Amoroso PJ (June 2000). "Cigarette smoking and suicide: a prospective study of 300,000 male active-duty Army soldiers". American Journal of Epidemiology. 151 (11): 1060–3. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010148. PMID 10873129.

- Breslau N, Schultz LR, Johnson EO, Peterson EL, Davis GC (March 2005). "Smoking and the Risk of Suicidal Behavior: A Prospective Study of a Community Sample". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (3): 328–34. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.328. PMID 15753246.

- Murphy JM, Horton NJ, Monson RR, Laird NM, Sobol AM, Leighton AH (September 2003). "Cigarette smoking in relation to depression: historical trends from the Stirling County Study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (9): 1663–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1663. PMID 12944343.

- Lembke A, Johnson K, DeBattista C (August 2007). "Depression and smoking cessation: does the evidence support psychiatric practice?". Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 3 (4): 487–93. PMC 2655079. PMID 19300577.

- Aronson KR, Almeida DM, Stawski RS, Klein LC, Kozlowski LT (December 2008). "Smoking is Associated with Worse Mood on Stressful Days: Results from a National Diary Study". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 36 (3): 259–69. doi:10.1007/s12160-008-9068-1. PMC 2873683. PMID 19067100.

- Ried LD, Tueth MJ, Handberg E, Kupfer S, Pepine CJ (2005). "A Study of Antihypertensive Drugs and Depressive Symptoms (SADD-Sx) in Patients Treated With a Calcium Antagonist Versus an Atenolol Hypertension Treatment Strategy in the International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study (INVEST)". Psychosomatic Medicine. 67 (3): 398–406. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000160468.69451.7f. PMID 15911902. S2CID 27978181.

- Patten, SB; Love, EJ (1993). "Can drugs cause depression? A review of the evidence". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 18 (3): 92–102. PMC 1188504. PMID 8499431.

- Bremner JD, McCaffery P (February 2008). "The neurobiology of retinoic acid in affective disorders". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 32 (2): 315–31. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.001. PMC 2704911. PMID 17707566.

- Debien C, De Chouly De Lenclave MB, Foutrein P, Bailly D (2001). "Alpha-interferon and mental disorders". L'Encéphale. 27 (4): 308–17. PMID 11686052.

- Robert Davies; Ghouse Ahmed; Tegwedd Freer (2000). "Chronic exposure to organophosphates: background and clinical picture". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 6 (3): 187–192. doi:10.1192/apt.6.3.187.

- Bowden CL (January 2001). "Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression". Psychiatric Services. 52 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.51. PMID 11141528.

- Matza LS, Rajagopalan KS, Thompson CL, de Lissovoy G (November 2005). "Misdiagnosed patients with bipolar disorder: comorbidities, treatment patterns, and direct treatment costs". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (11): 1432–40. doi:10.4088/jcp.v66n1114. PMID 16420081.

- Akiskal HS, Benazzi F (2006). "The DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories of recurrent [major] depressive and bipolar II disorders: Evidence that they lie on a dimensional spectrum". Journal of Affective Disorders. 92 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.035. PMID 16488021.

- Hvas AM, Juul S; Bech P, Nexø E (2004). "Vitamin B6 Level Is Associated with Symptoms of Depression". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 73 (6): 340–3. doi:10.1159/000080386. PMID 15479988. S2CID 37706794.

- Coppen A, Bolander-Gouaille C (January 2005). "Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 19 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1177/0269881105048899. PMID 15671130. S2CID 4828454.

- Rao NP, Kumar NC, Raman BR, Sivakumar PT, Pandey RS (2008). "Role of vitamin B12 in depressive disorder — a case report☆". General Hospital Psychiatry. 30 (2): 185–6. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.002. PMID 18291301.

- "Study Links Brain Fatty Acid Levels To Depression". ScienceDaily. Bethesda, MD: American Society For Biochemistry And Molecular Biology. 2005-05-25. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK.; et al. (April 2007). "Depressive symptoms, omega-6:omega-3 fatty acids, and inflammation in older adults". Psychosom. Med. 69 (3): 217–224. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180313a45. PMC 2856352. PMID 17401057.

- Dinan T, Siggins L, Scully P, O'Brien S, Ross P, Stanton C (January 2009). "Investigating the inflammatory phenotype of major depression: Focus on cytokines and polyunsaturated fatty acids". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 43 (4): 471–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.06.003. PMID 18640689.

- Lustberg L, Reynolds CF (June 2000). "Depression and insomnia: questions of cause and effect". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 4 (3): 253–262. doi:10.1053/smrv.1999.0075. PMID 12531168.

- Wilson, S. J.; et al. (2 September 2010). "British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders". J Psychopharm. 24 (11): 1577–601. doi:10.1177/0269881110379307. PMID 20813762. S2CID 16823040.

- Skidmore FM, Drago V, Foster PS, Heilman KM (2009). "Bilateral restless legs affecting a phantom limb, treated with dopamine agonists". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 80 (5): 569–70. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.152652. PMID 19372293. S2CID 23584726.

- Lee HB, Hening WA, Allen RP, et al. (2008). "Restless Legs Syndrome is Associated with DSM-IV Major Depressive Disorder and Panic Disorder in the Community". Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 20 (1): 101–5. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20.1.101. PMID 18305292.

- Harris M, Glozier N, Ratnavadivel R, Grunstein RR (December 2009). "Obstructive sleep apnea and depression". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 13 (6): 437–44. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.001. hdl:2328/26226. PMID 19596599.

- Dagan Y (2002). "Circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD)" (PDF). Sleep Med Rev. 6 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1053/smrv.2001.0190. PMID 12531141. Archived from the original (PDF: full text) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

Early onset of CRSD, the ease of diagnosis, the high frequency of misdiagnosis and erroneous treatment, the potentially harmful psychological and adjustment consequences, and the availability of promising treatments, all indicate the importance of greater awareness of these disorders.

Bibliography

- A Dose of Sanity: Mind, Medicine, and Misdiagnosis by Sydney Walker. John Wiley & Sons, 1997. ISBN 0-471-19262-7