Nasal septum deviation

Nasal septum deviation is a physical disorder of the nose, involving a displacement of the nasal septum. Some displacement is common, affecting 80% of people, mostly without their knowledge.[1]

| Deviated septum | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Deviated nasal septum (DNS) |

| |

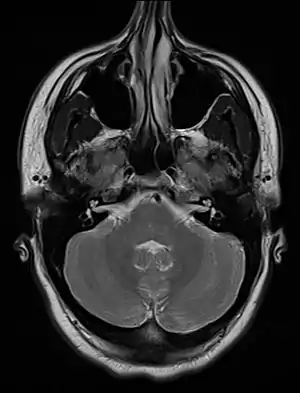

| An MRI image showing a congenitally deviated nasal septum, bowed to the left between the eye sockets | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

Signs and symptoms

The nasal septum is the bone and cartilage in the nose that separates the nasal cavity into the two nostrils. The cartilage is called the quadrangular cartilage and the bones comprising the septum include the maxillary crest, vomer, and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid. Normally, the septum lies centrally, and thus the nasal passages are symmetrical.[2] A deviated septum is an abnormal condition in which the top of the cartilaginous ridge leans to the left or the right, causing obstruction of the affected nasal passage.

It is common for nasal septa to depart from the exact centerline; the septum is only considered deviated if the shift is substantial or causes problems.[3] By itself, a deviated septum can go undetected for years and thus be without any need for correction.[3]

Symptoms of a deviated septum include infections of the sinus and sleep apnea, snoring, repetitive sneezing, facial pain, nosebleeds, mouth breathing, difficulty with breathing and mild to severe loss of the ability to smell.[1][4] Only more severe cases of a deviated septum will cause symptoms of difficulty breathing and require treatment.[1]

Causes

It is most frequently caused by impact trauma, such as by a blow to the face.[3] It can also be a congenital disorder, caused by compression of the nose during childbirth.[3] Deviated septum is associated with genetic connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.[5]

Diagnosis

Nasal septum deviation is the most common cause of nasal obstruction.[6] A history of trauma to the nose is often present including trauma from the process of birth or microfractures.[6] A medical professional, such as an otorhinolaryngologist (ears, nose, and throat doctor), typically makes the diagnosis after taking a thorough history from the affected person and performing a physical examination.[6] Imaging of the nose is sometimes used to aid in making the diagnosis as well.[6]

Treatment

Medical therapy with nasal sprays including decongestants, antihistamines, or nasal corticosteroid sprays is typically tried first before considering a surgical approach to correct nasal septum deviation.[6] Medication temporarily relieves symptoms, but does not correct the underlying condition. Non-medical relief can also be obtained using nasal strips.

A minor surgical procedure known as septoplasty can cure symptoms related to septal deviations. The surgery lasts roughly one hour and does not result in any cosmetic alteration or external scars. Nasal congestion, pain,[7] drainage or swelling may occur within the first few days after the surgery.[8] Recovery from the procedure may take anywhere from two days to four weeks to heal completely. Septal bones never regrow. If symptoms reappear they are not related to deviations. Reappearance of symptoms may be due to mucosal metaplasia of the nose. There are times also when the surgery also may be unsuccessful, leading to a continuation of the symptoms.

Complications of septoplasty

- Adhesions and synechiae between septal mucosa and lateral nasal wall

- Dropped nasal tip due to resection of the caudal margin

- External nasal deformity[6]

- Incomplete correction with persistent nasal symptoms[6]

- Nasal septum perforation[6] due to bilateral trauma of the mucoperichondrial flaps opposite each other.

- Saddle nose due to over-resection of the dorsal wall of the septal cartilage

- Scarring inside the nose and nose bleeding[6]

- Septal hematoma[6] and septal abscess.

See also

References

- Robinson, Jennifer (11 December 2016). "What Is a Deviated Septum?". WebMD.

- "Fact Sheet: Deviated Septum". Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Metson, Ralph; Mardon, Steven (5 April 2005). The Harvard Medical School Guide to Healing Your Sinuses. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 159–161. ISBN 978-0-07-144469-9.

- "Disorders of Smell & Taste". American Rhinologic Society. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Child, AH (November 2017). "Non-cardiac manifestations of Marfan syndrome". Annals of Cardiothoracic Surgery (Review). 6 (6): 599–609. doi:10.21037/acs.2017.10.02. PMC 5721104. PMID 29270372.

- Fettman, N; Sanford, T; Sindwani, R (April 2009). "Surgical management of the deviated septum: techniques in septoplasty". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 42 (2): 241–52. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.005. PMID 19328889.

- Fujiwara, Takashi; Kuriyama, Akira; Kato, Yumi; Fukuoka, Toshio; Ota, Erika (23 August 2018). Cochrane ENT Group (ed.). "Perioperative local anaesthesia for reducing pain following septal surgery". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD012047. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012047.pub2. PMC 6513247. PMID 30136717.

- "Septoplasty: Recovery and Outlook". my.clevelandclinic.org. Cleveland Clinic.