Death and state funeral of the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, died on 14 September 1852, aged 83. He was the commander of British forces and their allies in the Peninsular War and at the Battle of Waterloo, which finally ended the Napoleonic Wars, and served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Although Wellington's political career had led to his unpopularity because of his opposition to the Great Reform Act, in old age it was his military career which was remembered and he was revered as a national hero. His state funeral on 18 November at St Paul's Cathedral in London was the grandest of any in Britain during the 19th century.[1]

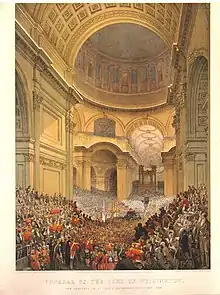

Wellington's funeral procession arriving at St Paul's Cathedral (print by George Baxter, 1852) | |

| Date |

|

|---|---|

| Location |

|

| Burial | Crypt of St Paul's |

Death

In his last years, Wellington lived at Walmer Castle on the Kent coast, the official residence of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, an honorary appointment which he had held since 1829.[2] On 13 September 1852, the 83 year-old duke had risen early, played with his visiting grandchildren and eaten venison for dinner. His valet woke him at 6 am on the following morning, but an hour later, a maid reported strange noises suggesting that he was ill. At 9 am, Dr Hulke, an apothacary arrived, who suggested a cup of tea, but this brought on a seizure. Treatments tried by Hulke, assisted by his son and the local doctor, included a emetic, poultices applied to the legs and tickling the jaw with a feather. At about 2 pm, the duke's valet suggested that he might be more comfortable in an arm chair, rather than the military camp bed in which he always slept, but the old man died after the move,[3] at 3:25 pm.[4] Urgent telegraphs had been sent to London, requesting the attendance of eminent surgeons Sir William Fergusson and John Robert Hume, but they were both in Scotland; a Dr Williams was dispatched instead, but arrived too late to assist.[5]

His body was embalmed before being sealed in his coffin, and remained in his bedroom at Walmer while preparations for the funeral began.[6] During this time, the coffin was guarded by detachments from the Rifle Brigade, a regiment in which Wellington held the ceremonial post of colonel-in-chief.[7] On 9 and 10 November local people were allowed to pay their respects; some 9,000 queued on the beach at Walmer to file past the coffin inside the castle.[8]

Preparations

Wellington had expressed a wish that he be buried at Walmer,[7] but at Queen Victoria's insistence, planning for a great state funeral started at once, to be financed by the sum of £10,000 voted through by Parliament (equivalent to £1,155,966 in 2021).[9] During that process, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli, delivered an eloquent eulogy to the House of Commons praising Wellington's character and achievements; this was marred when it was found that part of the speech had been plagiarised from an 1829 panegyric given by Adolphe Thiers for Marshal Saint-Cyr.[10]

Victoria also stipulated that Wellington be interred at St Paul's Cathedral, alongside Britain's other great Napoleonic War hero, Lord Nelson.[11] While preparations were in hand, the queen also felt that the duke should not be left without funeral rites for such a long time and accordingly, the Funeral Service from the Book of Common Prayer was read over the coffin at Walmer with only the duke's close relatives present and the text was not used at the later public service in St Paul's.[12] Meanwhile, special lighting and temporary wooden galleries to accommodate 10,000 people were installed in the cathedral itself,[13] while some of the windows were painted black with the intention of creating an atmosphere of gloom.[14]

The Poet Laureate, Alfred Tennyson, wrote a lengthy poem, Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington, which he completed and had printed by 16 November, two days before the funeral. The work had not been commissioned, but was written "because it was expected". It received mixed critical reviews.[1]

Funeral car

The original design for Wellington's hearse had been commissioned from the royal undertakers, Messers Ranting of St James, but the submitted proposal was rejected by the Earl Marshal, the 13th Duke of Norfolk, who was responsible for the ceremonial aspects of the funeral.[11] The project then passed to the Department of Practical Art, where Henry Cole and Richard Redgrave collaborated on a new design with German architect Gottfried Semper. The concept was inspired by the putative reconstruction of Alexander the Great's funeral car by French archeologist Quatremère de Quincy.[15] It was to be substantially built, being intended to be preserved for posterity. The final design was personally approved by Albert, Prince Consort.[11]

.jpg.webp)

The enormous carriage measured 27 feet (8.2 m) long, 11 feet (3.4 m) wide and 17 feet (5.2 m) tall, the main body of which was cast in 12 tons of solid bronze,[11] said to have been sourced from French cannons captured at the Battle of Waterloo.[16] It was supported on six large wheels, none of which were steerable, decorated with lion's heads and dolphins.[17] The coffin rested on a 6 feet (1.8 m) high bier, itself mounted on a podium decorated with panels bearing the names of Wellington's victories. Around this podium were mounted military colours and trophies of arms composed of real weapons from the Royal Armouries at the Tower of London. Four large posts at the corners, made to resemble halberds, supported a canopy of embroidered Indian fabric. These halberds were able to be lowered so that the car would be able to pass under Temple Bar, the gatehouse which spanned the roadway on the route to St Paul's.[17] The immense weight of the duke's quadruple coffin, made of pine, oak, lead and mahogany,[18] required another mechanism which could rotate the bier to allow it to be dismounted. It was to be drawn by a team of twelve horses in ranks of three.[17]

The whole project, from design to manufacture, was completed in three weeks, which was hailed as a triumph of British industry.[19] Critical reaction to the funeral car was varied; Victoria described it as "very gorgeous"[20] and the Illustrated London News said that it was "magnificent" and "a wonderful proof of English capacity". However, the diarist Charles Greville called it "tawdry, cumbrous and vulgar", while the essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle wrote that it was a "monstrous bronze mass" and an "incoherent muddle of expensive palls, flags, sheets and poles... more like one of the street carts that hawk doormats than a bier for a hero".[21]

Lying in State

At 6 pm the evening of 10 November, Wellington's coffin was taken by hearse in a torchlight procession to Deal railway station, escorted by the Rifle Brigade and with minute guns being fired from Walmer, Deal and Sandown Castles. The funeral train reached Bricklayers Arms railway station in Southwark at 12.30 am, from where the hearse was escorted by a squadron of the Life Guards to the Royal Hospital Chelsea, where the duke was to lie in state; the coffin was placed in the Great Hall at 3 am.[22] The hall had previously been draped with black cloth to resemble a large tent and was lit only by candles, mounted on four rows of large candelabras. At the far end of the hall, the coffin, covered in red velvet, was mounted on a dias under a black canopy, surrounded by twelve more candelabras and the duke's batons.[23] The coffin was guarded by Yeomen of the Guard and Grenadier Guards, with reversed arms.[24]

Before the hall was opened to the public, it was visited by Queen Victoria, along with Albert and their children; the queen was overcome with emotion and had to be assisted out.[25] After the Chelsea Pensioners had been allowed to pay their respects, many of whom had served under Wellington, followed by parties of Guards and some local schools, the public were admitted.[26] The queue stretched back as far as Ebury Square near Victoria Station and entailed a wait of up to five and a half hours.[27] Such were the crowds that two women, Sarah Bean and Charlotte Cooke,[28] were crushed to death on 13 November.[29]

On 17 November, the hall closed at 5 pm. The Metropolitan Police estimated the number of visitors on the final day at 55,800.[11] The total number over the five days was estimated at almost half a million.[16] Shortly after 9 pm, a hearse escorted by Life Guards arrived to transfer the coffin to Horse Guards.[11] On the same day, heavy rain combined with a storm surge in the River Thames caused record flooding in parts of London, an event that became known as "the Duke of Wellington’s Flood".[30]

Procession

Wellington's coffin was placed overnight in his former office at Horse Guards, before being transferred in the early morning to the funeral car, which was parked in a temporary pavilion just outside. Before dawn, troops began to assemble for the procession, six battalions of infantry on Horse Guards Parade, eight squadrons of cavalry and seventeen artillery pieces in St James's Park; a total of some 10,000 men. Included were a representatives of each regiment of the British Army, as well officers representing the presidency armies of the East India Company. Also included were carriages carrying Wellington's relatives, senior British and allied officers and members of the royal family, the foremost being Albert, Prince Consort.[31]

At 8 am accompanied by the firing of minute guns, the procession began to move off, under the command of Prince George, Duke of Cambridge. The funeral car, drawn by draft horses borrowed from a brewery,[32] was preceded by the band of the Grenadier Guards playing Handel's Dead March in Saul and other funereal music.[11] The duke's distinctive cocked hat and sword were mounted on the pall-covered coffin. Following behind was a groom leading the duke's horse, with boots reversed in the stirrups.[32] Although there had been some early rain, the sun broke through as the procession started. The route took the parade past Buckingham Palace, up Constitution Hill to Hyde Park Corner, then along Piccadilly, St James's Street and Pall Mall. After passing through Trafalgar Square it entered The Strand, then Fleet Street and Ludgate Hill to St Paul's. Following tradition, Victoria did not attend the funeral, but watched the procession from Buckingham Palace before going to St James's Palace to see it pass for a second time.[33]

When the procession had passed through Wellington Arch at Hyde Park Corner, the location of the duke's London home, Apsley House, the funeral car had to be manhandled around the sharp bend, because it lacked steerable axles. In Pall Mall, at a point opposite the Duke of York's Column, the gas company had recently dug up the road leaving a patch of sand and mud, in which the wheels of the funeral car sank, causing it to list sideways; the coffin was only saved from falling by having been secured with copper wire.[34] The car was eventuially hauled free with the assistance of sixty policemen.[35] A contingent of Chelsea Pensioners joined the procession at Charing Cross. At Temple Bar, which had been transformed into a triumphal arch, adorned with wreaths, urns and draped with black cloth,[11] the procession entered the City of London; it was joined there by the Lord Mayor and Aldermen in coaches, bringing the total length of the procession to 2 miles (3.2 km).[36] By the time the funeral car reached Ludgate Hill, the twelve horses drawing it were close to exhaustion and sailors had to help push it up the gradient to the cathedral.[35] The procession had taken four and a half hours.[1] It was watched by an immense crowd, estimated by the police at a million and a half, who had travelled from all over the United Kingdom by train and represented more than five percent of the total population.[16] Those who could not afford a place in one of the overlooking houses or in the temporary stands which had been erected along the route, packed the pavements. Despite press warnings of potential disorder,[37] the crowds maintained a respectful silence throughout. The sight of the them lifting their hats together as the coffin passed was said to resemble the rising of a flock of birds.[38]

Service

St Paul's had been filled with a huge congregation; various sources give figures of 10,000[14][39] 12,000 to 15,000[40] or 20,000.[41][42] No thought had been given to directing people to their seats and serious crush accidents were only narrowly avoided in the temporary passages and stairways behind the wooden galleries.[43] The printed orders of service were given to the choirboys to distribute, who being unable access the packed upper galleries, scatterd them about the lower seats resulting in a general scramble. Those who had too many service sheets screwed them up into balls and threw them up to those seated above.[44] On the arrival of the funeral car, the mechanism to rotate and dismount the bier and coffin failed and it took an hour to solve the problem. Meanwhile, the great west door of the cathedral was left open to the cold wind, to the distress of the elderly Chelsea Pesioners standing close by.[38]

The entrance procession, when it finally got underway, was accompanied by Psalms 39 and 90,[33] set to a chant written by the duke's father, the Earl of Mornington, and sung by the combined choirs of St Paul's, Westminster Abbey and the Chapel Royal, a total of 120 men and boys. An orchestra was seated in a gallery by the organ.[45] the procession was headed by the clergy, led by the Bishop of London, Charles James Blomfield and the Dean of St Paul's, Henry Hart Milman. The bier was preceded by heralds carrying the duke's armorial bearings and military representatives of the allied nations carrying his batons. Alongside were senior British general officers acting as pall-bearers and it was followed by his eldest son, Arthur Wellesley, 2nd Duke of Wellington, in a long mourning cloak, the train of which was carried by his young nephews, acting as pages.[46]

During the service, one of two new anthems was sung, If we believe that Jesus died, composed for the occasion by John Goss, the organist at St Paul's. After the lesson, the Nunc dimittis was sung to a chant arranged by Goss from Beethoven's Symphony No. 7. This was followed by Goss's second anthem, And the King said, which Prince Albert reported "had made everyone weep". Goss's anthem had been written to move seamlessly into Handel's Dead March in Saul,[47] which was played while the coffin was dramatically lowered through an opening in the floor to the crypt below, by means of a system of hidden pulleys.[48] Then followed the traditional Funeral Sentences by Croft and Purcell, and after the collect, His body is buried in peace by Handel. After the Garter Principal King of Arms had proclaimed the duke's titles, a chorale by Felix Mendelssohn, Sleepers Awake!, was sung in English, probably at the suggestion of Prince Albert. After the blessing, "upon a given signal", the guns fired at the Tower of London and a fanfare sounded at the west door, bringing the service to a close.[47]

Guests

Royal family

Wellesley family

- The Duke of Wellington, the Duke's son

- Lord Charles Wellesley, the Duke's son

- The Earl of Mornington, the Duke's nephew

- Viscount Wellesley, the Duke's grandnephew[50]

- The Lord Cowley, the Duke's nephew

- Hon. William Wellesley, the Duke's grandnephew

- Hon. Gerald Wellesley, the Duke's nephew

- Rev. Henry Wellesley, the Duke's nephew[51]

Bearers of Wellington's batons

- Spanish Army, Mariano Téllez-Girón, 12th Duke of Osuna

- Russian Army, Andrei Ivanovich Gorchakov

- Prussian Army, August Ludwig von Nostitz

- Portuguese Army, António José Severim de Noronha, 1st Duke of Terceira

- Army of the Netherlands, Antonie Frederik Jan Floris Jacob van Omphal

- Hanovarian Army, Baron Hugh Halkett

- British Army, Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey[52]

Pall bearers

Other notable mourners

Aftermath

After being lowered through the floor of St Paul's, Wellington's coffin came to rest on top of Nelson's sarcophagus. There it remained until November 1853, when it was finally brought to the ground. However, Wellington's own sarcophagus was not completed until April 1858. It was made from a single piece of Cornish porphyry,[56] of a type called Luxullianite, which was found in a field near Lostwithiel.[57] A monument to stand in the main body of the cathedral above was designed in 1857 by Alfred Stevens, but was completed by John Tweed and initially placed in the Chapel of St Michael and St George before being moved to its present position between two columns in the nave; it was not finally completed until 1912.[58] The funeral car was preserved in the crypt of St Paul's until 1981, when it was moved to Wellington's country mansion, Stratfield Saye House.[59]

References

- Allis 2012, p. 105

- Holmes 2003, pp. 298-279

- Holmes 2003, p. 293

- Longford 1975, p. 490

- Gleig 1865, p. 457

- Hibbert 1997, p. 399

- Gleig 1865, p. 458

- Holmes 2003, p. 297

- "Funeral of the Duke of Wellington". www.parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Maxwell 1884, pp. 465-470

- Ridgley, Paul (12 April 2019). "WELLINGTON'S DEATH: LYING IN STATE AND FUNERAL PROCESSION". www.waterlooassociation.org.uk. Waterloo Association. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- Garlick 1998, p. 114

- Quinn 2015, Introduction p. xii

- Burns 2004, p. 384

- Garlick 1998, pp. 116 & 120-121

- Laqueur 2015, p. 334

- Garlick 1998, p. 117

- Muir 2015, p. 569

- Garlick 1998, p. 116

- Blaker, Michael (25 April 2021). "Wellington's Funeral Carriage". victorianweb.org. The Victorian Web. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Garlick 1998, p. 120

- Gleig 1865, pp. 458-459

- Longford 1975, pp. 491-492

- Colburn's 1852, p. 592

- Gleig 1865, p. 459

- Colburn's 1852, pp. 592-593

- Richardson 2001, p. 277

- Sinnema 2000, p. 37

- Colburn's 1852, p. 593

- "STORM EVENT - 17TH NOVEMBER 1852". www.surgewatch.org. University of Southampton. 17 November 1852. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Maxwell 1865, p. 470-471

- Longford 1975, p. 493

- Muir 2015, p. 572

- Garlick 1999, p. 117

- Holmes 2003, p. 298

- Maxwell 1865, p. 480

- Sinnema 2000, p. 34

- Longford 1975, p. 494

- Stocqueler 1852, p. 278

- Colburn's 1852, p. 605

- Sinnema 2006, p.12

- Garlick 1999, p. 113

- Colburn's 1852, p. 607

- Sinnema 2000, p. 41

- Range 2016, p. 244

- Maxwell 1865, pp. 480-481

- Range 2016, pp. 244-246

- Pearsall 1999, p. 379

- Young 1852, p. 14

- Young 1852, p. 16

- "No. 21388". The London Gazette. 6 December 1852. p. 3551.

- Young 1852, pp. 14-15

- Young 1852, p. 15

- Young 1852, p. 13

- Young 1852, p. 24

- Pearsall 1999, p. 384

- Lobley 1892, p. 46

- Longford 1975, p. 495

- Garlick 1999, p. 123

Sources

- Allis, Michael (2012). British Music and Literary Context: Artistic Connections in the Long Nineteenth Century. Woodbrige, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843837305.

- Burns, Arthur (2004). St. Paul's: The Cathedral Church of London, 604-2004. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300092769.

- Colburn's United Service Magazine and Naval and Military Journal: Volume 70. London: Colburn & Co. 1852.

- Garlick, Harry (1999). The Final Curtain: State Funerals and the Theatre of Power. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi B.V. ISBN 978-9042005686.

- Gleig, George Robert (1865). The Life of Arthur, Duke of Wellington. London: Longmans, Green, Reader and Dyer.

- Holmes, Richard (2003). Wellington: the Iron Duke. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0007137503.

- Laqueur, Thomas W. (2015). The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691157788.

- Lobley, J. Logan (1892). "Building stones, their structure and origin". Stone: An Illustrated Magazine. V (June–November): 45–47. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Longford, Elizabeth (1975). Wellington, Pillar of State. St Albans, Herts: Panther Books Ltd. ISBN 9780586041550.

- Maxwell, William Hamilton (1865). Life, Military and Civil, of the Duke of Wellington. London: Bell & Daldey.

- Muir, Rory (2015). Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace 1814–1852. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300187861.

- Pearsall, Cornelia D. J. (1999). "Burying the Duke: Victorian Mourning and the Funeral of the Duke of Wellington". Victorian Literature and Culture. 27 (2): 365–393. doi:10.1017/S1060150399272026. JSTOR 25058460. S2CID 162303822. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Quinn, Iain, ed. (2015). John Goss: Complete Anthems. Middleton WI: A-R Editions. ISBN 978-0895798176.

- Range, Matthias (2016). British Royal and State Funerals: Music and Ceremonial since Elizabeth I. Martlesham, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1783270927.

- Richardson, John (2001). The Annals of London: A Year By Year Record Of A Thousand Years Of History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd. ISBN 978-1841881355.

- Sinnema, Peter W. (2000). "Anxiously Managing Mourning: Wellington's Funeral and the Press". Victorian Review. 25 (2. Winter, 2000): 30–60. doi:10.1353/vcr.2000.0030. JSTOR 27794933. S2CID 162931578. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Sinnema, Peter W. (2006). The Wake of Wellington: Englishness in 1852. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0821416792.

- Stocqueler, Joachim Hayward (1853). The Life Of Field Marshal The Duke Of Wellington: Volume II. London: Ingram, Cooke and Co.

- Tennyson, Alfred (1852). Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington. London: Edward Moxon.

- Turner, Michael J. (2004). Independent Radicalism in Early Victorian Britain. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0275973865.

- Wood, Claire (2015). Dickens and the Business of Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107098633.

- Young, Charles George (1852). The Order of Proceeding and Ceremonies observed in the Public Funeral of the late Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, K.G. London: London Gazette Office.