De Rays Expedition

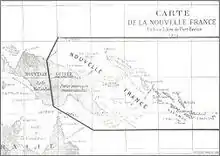

The Third de Rays Expedition, or simply the de Rays Expedition, was the third New Guinea expedition of Marquis de Rays, a French nobleman who attempted to start a colony in the South Pacific.[1][2] The expedition attempted to establish a colony in a place the marquis called La Nouvelle France,[2][3] or New France,[4] which was the island now referred to as New Ireland[2] in the Bismarck Archipelago of present-day Papua New Guinea.[1] Three hundred and forty[2][4] Italian colonists aboard the ship India set sail from Barcelona in 1880[2] for this new land, seeking relief from the poor conditions in Italy at that time.[1] One hundred and twenty-three colonists died before being rescued by Australian authorities. The marquis is widely believed to have deliberately misled the colonists, distributing literature claiming a bustling settlement (with numerous public buildings, wide roads, and rich, arable land) existed at Port Breton.[4] Port Breton, however, was actually located at the remote south-western corner of New Ireland, where jungle covered mountains descend steeply into the sea.[3]

The Paradise of New France

In 1879, advertising was distributed widely throughout Europe by the Marquis telling of a paradise empire called New France. The advertising was cleverly worded and described the capital, Port Breton,[3] as a bustling new colony which had been successfully colonised by two prior expeditions. The advertising described majestic public buildings and a beautiful climate, similar to that of the French Riviera. There were also reports of great wide roads and arable farmland.[3]

Three hundred and forty colonists from Veneto in Italy[4] joined the expedition, and each paid the marquis 1,800 francs in gold or were allowed the option to offer their services in labour for five years.[1] For this trade they were offered twenty hectares of land and a four-room house,[3] as well as transport to the new colony and rations amounting to six months for those who paid in gold, and five years for those who offered their labour.[1] The marquis received over seven million francs for his four ill-fated expeditions.[4]

The governments of both France and Italy claimed the expedition was a scam, and announced they would not allow the voyage to take place, citing the safety of the Italians.[1] The Royal Investigation Bureau in Milan went as far as to order a directive that no Italian involved in the expedition would be issued a passport for travel. Many colonists did not believe the authorities, and De Rays organised the voyage to depart from Barcelona, Spain, to avoid confrontation with the French and Italian authorities.[1]

The voyage

Fifty families were sent to Barcelona and boarded the India bound for Port Breton.

The voyage to New France aboard the India left on 9 July 1880. The journey to New Ireland took more than three months, and colonists were forced to live on board in appalling, cramped conditions. Disease and tension were rife on the ship, and ventilation and rations were in short supply, causing deaths in transit. The ship, and more than three hundred colonists, made landfall on 14 October 1880.[2]

Settlement in Port Breton

Upon arriving in Port Breton, the colonists discovered there was no town, settlement, or empire of New France.[5] Housing had not been built for them as promised, but they were able to salvage from the now derelict India and the remains of the two previous expeditions some three weeks supplies,[6] bricks,[6] notebooks and the makings of a mill.[6] The mill was never used, and parts of the grindstone can still be found at Kavieng.[6] The stone itself is mounted as a memorial in Rabaul.[7]

Located at the feet of the Verron Range, that area of New Ireland is mostly dense tropical rainforest and the settlers were unable to carve out the farmland they had been promised. Many started to fall sick after their weakening journey on the India and were unable to ward off new tropical diseases such as malaria.[2][6] Starvation was also a major concern, and there were also some reports of clashes with the indigenous population.[2][6] About a hundred settlers died in Port Breton from disease and malnutrition.[2][3]

After two months, a smaller previous expedition ship, the Genil, was sent out in desperation from the failed colony to find food and supplies.[3] Settlers waited two more months for its return before casting off on the India to try to find a nearby colony that could house the starving refugees. There were now just over two hundred and thirty settlers remaining. By coincidence, the Genil arrived back at the port on the same day the India left, but the two ships did not sight each other.[3]

The voyage to Nouméa

Settlers reportedly instructed the captain of the India to set sail for Sydney, Australia, but instead, the ship sailed to Nouméa in the French colony of New Caledonia,[4] which was at that time a penal colony. The settlers hoped to continue to Sydney, but the French authorities declared the India unseaworthy and refused to allow it to leave port. Due to an apparent dislike of the French,[1] and a desire to not reside in a penal colony, the Italians appealed to the British consul for aid. Sir Henry Parkes, the colonial secretary of New South Wales,[3] responded to their request[4] and arranged travel for the settlers on the James Patterson[1][3] to Sydney. Two hundred and seventeen settlers remained upon arrival in Sydney.[3][4]

Settlement in New Italy

A handful of Port Barton settlers resettled in Cairns, Australia but the majority settled in New South Wales, forming the settlement known as Little Italy.[8] The colonists found themselves in temporary accommodations for a short while, in the Old Agricultural Hall,[9] as a media storm swelled around them. Eventually, they were hired out by the colony to English-speaking families for thirty pounds a year, in an attempt to force the Italians to assimilate into Australian culture.[4][9] Families were torn apart, and many of the colonists hoped to settle an area of New South Wales, as enough skilled tradesmen existed among the settlers to form an established settlement. Hearing of land becoming available in the north, some colonists surveyed and individually claimed[4][9] areas that collectively formed a 3,000-acre (12 km2) parcel, and established the settlement of New Italy[2][9] on the Richmond River near Woodburn in 1882. Many of the former colonists moved to that area.[4][9]

The settlement is now deserted, but a museum exists on the site as part of the New Italy Visitor Centre, cafe and rest area, adjacent to the A1 Pacific Highway.[1]

References

- "History and Passenger Lists of the Marquis de Ray Expedition to New Ireland in 1880". KMB Associates. 2003.

- "story of the Italian settlement near Woodburn, NSW". Teaching Heritage. 2001.

- "The Voyage". New Italy Museum. 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- "ITALIAN PIONEERS, From the forthcoming publication, The Australian People,". Ilma O'Brien. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007.

-

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from La Nouvelle France: Nineteenth century propaganda (7 September 2022) by Stacey Larner published by the State Library of Queensland under CC BY licence, accessed on 17 January 2023.

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from La Nouvelle France: Nineteenth century propaganda (7 September 2022) by Stacey Larner published by the State Library of Queensland under CC BY licence, accessed on 17 January 2023.

- "New Ireland Province". Papua New Guinea Business and Tourism. 2002. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2007.

- "Photograph of the Stone grinding wheel from Marquis de Rays' doomed New Ireland settlement".

-

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from La Nouvelle France: Nineteenth century propaganda (7 September 2022) by Stacey Larner published by the State Library of Queensland under CC BY licence, accessed on 17 January 2023.

This Wikipedia article incorporates text from La Nouvelle France: Nineteenth century propaganda (7 September 2022) by Stacey Larner published by the State Library of Queensland under CC BY licence, accessed on 17 January 2023.

- "Migration". New Italy Museum. 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

External links

- New Italy Museum website

- Blog - La Nouvelle France: Nineteenth century propaganda, State Library of Queensland.

- La Nouvelle France : journal de la colonie libre de Port-Breton, Oceanie, 1879- 1881 - digitised Journal issued to advertise the enterprise launched by the Marquis de Rays.