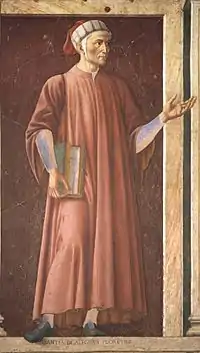

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (Italian: [ˈdante aliˈɡjɛːri]; c. 1265 – 14 September 1321), most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri[note 1] and often referred to as Dante (English: /ˈdɑːnteɪ, ˈdænteɪ, ˈdænti/,[3][4] US: /ˈdɑːnti/[5]), was an Italian[lower-alpha 1] poet, writer and philosopher.[7] His Divine Comedy, originally called Comedìa (modern Italian: Commedia) and later christened Divina by Giovanni Boccaccio,[8] is widely considered one of the most important poems of the Middle Ages and the greatest literary work in the Italian language.[9][10]

Dante Alighieri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. May 1265[1] Florence, Republic of Florence |

| Died | 14 September 1321 (aged c. 56) Ravenna, Papal States |

| Resting place | Tomb of Dante |

| Occupation | Statesman, poet, language theorist, political theorist |

| Language | Italian Tuscan Latin |

| Nationality | Florentine |

| Period | Late Middle Ages |

| Literary movement | Dolce Stil Novo |

| Notable works | Divine Comedy |

| Spouse | Gemma Donati |

| Children | 4, including Jacopo |

| Parents | Alighiero di Bellincione (father) Bella (mother) |

Dante is known for establishing the use of the vernacular in literature at a time when most poetry was written in Latin, which was accessible only to educated readers. His De vulgari eloquentia (On Eloquence in the Vernacular) was one of the first scholarly defenses of the vernacular. His use of the Florentine dialect for works such as The New Life (1295) and Divine Comedy helped establish the modern-day standardized Italian language. By writing his poem in the Italian vernacular rather than in Latin, Dante influenced the course of literary development, making Italian the literary language in western Europe for several centuries.[11] His work set a precedent that important Italian writers such as Petrarch and Boccaccio would later follow.

Dante was instrumental in establishing the literature of Italy, and is considered to be among the country's national poets and the Western world's greatest literary icons.[12] His depictions of Hell, Purgatory and Heaven provided inspiration for the larger body of Western art and literature.[13][14] He influenced English writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer, John Milton, and Alfred Tennyson, among many others. In addition, the first use of the interlocking three-line rhyme scheme, or the terza rima, is attributed to him. He is described as the "father" of the Italian language,[15] and in Italy he is often referred to as il Sommo Poeta ("the Supreme Poet"). Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio are also called the tre corone ("three crowns") of Italian literature.

Early life

Dante was born in Florence, Republic of Florence, in what is now Italy. The exact date of his birth is unknown, although it is generally believed to be around 1265.[18] This can be deduced from autobiographic allusions in the Divine Comedy. Its first section, the Inferno, begins, "Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita" ("Midway upon the journey of our life"), implying that Dante was around 35 years old, since the average lifespan according to the Bible (Psalm 89:10, Vulgate) is 70 years; and since his imaginary travel to the netherworld took place in 1300, he was most probably born around 1265. Some verses of the Paradiso section of the Divine Comedy also provide a possible clue that he was born under the sign of Gemini: "As I revolved with the eternal twins, I saw revealed, from hills to river outlets, the threshing-floor that makes us so ferocious" (XXII 151–154). In 1265, the sun was in Gemini between approximately 11 May and 11 June (Julian calendar).[19]

Dante claimed that his family descended from the ancient Romans (Inferno, XV, 76), but the earliest relative he could mention by name was Cacciaguida degli Elisei (Paradiso, XV, 135), born no earlier than about 1100. Dante's father, Alighiero di Bellincione,[20] was a White Guelph who suffered no reprisals after the Ghibellines won the Battle of Montaperti in the middle of the 13th century. This suggests that Alighiero or his family may have enjoyed some protective prestige and status, although some suggest that the politically inactive Alighiero was of such low standing that he was not considered worth exiling.[21]

Dante's family was loyal to the Guelphs, a political alliance that supported the Papacy and that was involved in complex opposition to the Ghibellines, who were backed by the Holy Roman Emperor. The poet's mother was Bella, probably a member of the Abati family.[20] She died when Dante was not yet ten years old. His father Alighiero soon married again, to Lapa di Chiarissimo Cialuffi. It is uncertain whether he really married her, since widowers were socially limited in such matters, but she definitely bore him two children, Dante's half-brother Francesco and half-sister Tana (Gaetana).[20]

Dante said he first met Beatrice Portinari, daughter of Folco Portinari, when he was nine (she was eight),[22] and he claimed to have fallen in love with her "at first sight", apparently without even talking with her.[23] When he was 12, however, he was promised in marriage to Gemma di Manetto Donati, daughter of Manetto Donati, member of the powerful Donati family.[20] Contracting marriages for children at such an early age was quite common and involved a formal ceremony, including contracts signed before a notary.[20] Dante claimed to have seen Beatrice again frequently after he turned 18, exchanging greetings with her in the streets of Florence, though he never knew her well.[24]

Years after his marriage to Gemma, he claims to have met Beatrice again; he wrote several sonnets to Beatrice but never mentioned Gemma in any of his poems. He refers to other Donati relations, notably Forese and Piccarda, in his Divine Comedy. The exact date of his marriage is not known; the only certain information is that, before his exile in 1301, he had fathered three children with Gemma (Pietro, Jacopo and Antonia).[20]

Dante fought with the Guelph cavalry at the Battle of Campaldino (11 June 1289).[25] This victory brought about a reformation of the Florentine constitution. To take part in public life, one had to enroll in one of the city's many commercial or artisan guilds, so Dante entered the Physicians' and Apothecaries' Guild.[26] In the following years, his name is occasionally recorded as speaking or voting in the various councils of the republic. A substantial portion of minutes from such meetings in the years 1298–1300 was lost, however, so the true extent of Dante's participation in the city's councils is uncertain.

Education and poetry

Not much is known about Dante's education; he presumably studied at home or in a chapter school attached to a church or monastery in Florence. It is known that he studied Tuscan poetry and that he admired the compositions of the Bolognese poet Guido Guinizelli—in Purgatorio XXVI he characterized him as his "father"—at a time when the Sicilian School (Scuola poetica Siciliana), a cultural group from Sicily, was becoming known in Tuscany. He also discovered the Provençal poetry of the troubadours, such as Arnaut Daniel, and the Latin writers of classical antiquity, including Cicero, Ovid and especially Virgil.[27]

Dante's interactions with Beatrice set an example of so-called courtly love, a phenomenon developed in French and Provençal poetry of prior centuries. Dante's experience of such love was typical, but his expression of it was unique. It was in the name of this love that Dante left his imprint on the dolce stil nuovo ("sweet new style", a term that Dante himself coined), and he would join other contemporary poets and writers in exploring never-before-emphasized aspects of love (Amore). Love for Beatrice (as Petrarch would express for Laura somewhat differently) would be his reason for writing poetry and for living, together with political passions. In many of his poems, she is depicted as semi-divine, watching over him constantly and providing spiritual instruction, sometimes harshly. When Beatrice died in 1290, Dante sought refuge in Latin literature.[28] The Convivio chronicles his having read Boethius's De consolatione philosophiae and Cicero's De Amicitia.

He next dedicated himself to philosophical studies at religious schools like the Dominican one in Santa Maria Novella. He took part in the disputes that the two principal mendicant orders (Franciscan and Dominican) publicly or indirectly held in Florence, the former explaining the doctrines of the mystics and of St. Bonaventure, the latter expounding on the theories of St. Thomas Aquinas.[24]

At around the age of 18, Dante met Guido Cavalcanti, Lapo Gianni, Cino da Pistoia and, soon after, Brunetto Latini; together they became the leaders of the dolce stil nuovo. Brunetto later received special mention in the Divine Comedy (Inferno, XV, 28) for what he had taught Dante: Nor speaking less on that account I go With Ser Brunetto, and I ask who are his most known and most eminent companions.[29] Some fifty poetical commentaries by Dante are known (the so-called Rime, rhymes), others being included in the later Vita Nuova and Convivio. Other studies are reported, or deduced from Vita Nuova or the Comedy, regarding painting and music.

Florence and politics

.jpg.webp)

Dante, like most Florentines of his day, was embroiled in the Guelph–Ghibelline conflict. He fought in the Battle of Campaldino (11 June 1289), with the Florentine Guelphs against Arezzo Ghibellines;[25][30] he fought as a feditore, responsible for the first attack.[31] He was among the escorts for Charles Martel of Anjou (grandson of Charles I of Anjou) when he came to Florence in 1294. To further his political career, he became a pharmacist. He did not intend to practice as one, but a law issued in 1295 required nobles aspiring to public office to be enrolled in one of the Corporazioni delle Arti e dei Mestieri, so Dante obtained admission to the Apothecaries' Guild. This profession was not inappropriate, since at that time books were sold from apothecaries' shops. As a politician, he accomplished little but held various offices over some years in a city rife with political unrest.

After defeating the Ghibellines, the Guelphs divided into two factions: the White Guelphs (Guelfi Bianchi)—Dante's party, led by Vieri dei Cerchi—and the Black Guelphs (Guelfi Neri), led by Corso Donati. Although the split was along family lines at first, ideological differences arose based on opposing views of the papal role in Florentine affairs. The Blacks supported the Pope and the Whites wanted more freedom from Rome. The Whites took power first and expelled the Blacks. In response, Pope Boniface VIII planned a military occupation of Florence. In 1301, Charles of Valois, brother of King Philip IV of France, was expected to visit Florence because the Pope had appointed him as peacemaker for Tuscany. But the city's government had treated the Pope's ambassadors badly a few weeks before, seeking independence from papal influence. It was believed that Charles had received other unofficial instructions, so the council sent a delegation that included Dante to Rome to ascertain the Pope's intentions.

Exile from Florence

Pope Boniface quickly dismissed the other delegates and asked Dante alone to remain in Rome. At the same time (1 November 1301), Charles of Valois entered Florence with the Black Guelphs, who in the next six days destroyed much of the city and killed many of their enemies. A new Black Guelph government was installed, and Cante dei Gabrielli da Gubbio was appointed podestà of the city. In March 1302, Dante, a White Guelph by affiliation, along with the Gherardini family, was condemned to exile for two years and ordered to pay a large fine.[32] Dante was accused of corruption and financial wrongdoing by the Black Guelphs for the time that Dante was serving as city prior (Florence's highest position) for two months in 1300.[33] The poet was still in Rome in 1302, as the Pope, who had backed the Black Guelphs, had "suggested" that Dante stay there. Florence under the Black Guelphs, therefore, considered Dante an absconder.[34]

Dante did not pay the fine, in part because he believed he was not guilty and in part because all his assets in Florence had been seized by the Black Guelphs. He was condemned to perpetual exile; if he had returned to Florence without paying the fine, he could have been burned at the stake. (In June 2008, nearly seven centuries after his death, the city council of Florence passed a motion rescinding Dante's sentence.)[35] In 1306–07, Dante was a guest of Moroello Malaspina in the region of Lunigiana.[36]

Dante took part in several attempts by the White Guelphs to regain power, but these failed due to treachery. Bitter at the treatment he received from his enemies, he grew disgusted with the infighting and ineffectiveness of his erstwhile allies and vowed to become a party of one. He went to Verona as a guest of Bartolomeo I della Scala, then moved to Sarzana in Liguria. Later he is supposed to have lived in Lucca with a woman named Gentucca. She apparently made his stay comfortable (and he later gratefully mentioned her in Purgatorio, XXIV, 37).[37] Some speculative sources claim he visited Paris between 1308 and 1310, and other sources even less trustworthy say he went to Oxford: these claims, first made in Boccaccio's book on Dante several decades after his death, seem inspired by readers who were impressed with the poet's wide learning and erudition. Evidently, Dante's command of philosophy and his literary interests deepened in exile and when he was no longer busy with the day-to-day business of Florentine domestic politics, and this is evidenced in his prose writings in this period. There is no real evidence that he ever left Italy. Dante's Immensa Dei dilectione testante to Henry VII of Luxembourg confirms his residence "beneath the springs of Arno, near Tuscany" in April 1311.[38]

In 1310, Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg marched into Italy at the head of 5,000 troops. Dante saw in him a new Charlemagne who would restore the office of the Holy Roman Emperor to its former glory and also retake Florence from the Black Guelphs. He wrote to Henry and several Italian princes, demanding that they destroy the Black Guelphs.[39] Mixing religion and private concerns in his writings, he invoked the worst anger of God against his city and suggested several particular targets, who were also his personal enemies. It was during this time that he wrote De Monarchia, proposing a universal monarchy under Henry VII.[40]

At some point during his exile, he conceived of the Comedy, but the date is uncertain. The work is much more assured and on a larger scale than anything he had written in Florence; it is likely he would have undertaken such a work only after he realized his political ambitions, which had been central to him up to his banishment, had been halted for some time, possibly forever. It is also noticeable that Beatrice has returned to his imagination with renewed force and with a wider meaning than in the Vita Nuova; in Convivio (written c. 1304–07) he had declared that the memory of this youthful romance belonged to the past.[41]

An early indication that the poem was underway is a notice by Francesco da Barberino, tucked into his Documenti d'Amore (Lessons of Love), probably written in 1314 or early 1315. Francesco notes that Dante followed the Aeneid in a poem called "Comedy" and that the setting of this poem (or part of it) was the underworld; i.e., hell.[42] The brief note gives no incontestable indication that Barberino had seen or read even the Inferno, or that this part had been published at the time, but it indicates composition was well underway and that the sketching of the poem might have begun some years before. (It has been suggested that a knowledge of Dante's work also underlies some of the illuminations in Francesco da Barberino's earlier Officiolum [c. 1305–08], a manuscript that came to light in 2003.[43]) It is known that the Inferno had been published by 1317; this is established by quoted lines interspersed in the margins of contemporary dated records from Bologna, but there is no certainty as to whether the three parts of the poem were each published in full or, rather, a few cantos at a time. Paradiso was likely finished before he died, but it may have been published posthumously.[44]

.jpg.webp)

In 1312, Henry assaulted Florence and defeated the Black Guelphs, but there is no evidence that Dante was involved. Some say he refused to participate in the attack on his city by a foreigner; others suggest that he had become unpopular with the White Guelphs, too, and that any trace of his passage had carefully been removed. Henry VII died (from a fever) in 1313 and with him any hope for Dante to see Florence again. He returned to Verona, where Cangrande I della Scala allowed him to live in certain security and, presumably, in a fair degree of prosperity. Cangrande was admitted to Dante's Paradise (Paradiso, XVII, 76).[45]

During the period of his exile, Dante corresponded with Dominican theologian Fr. Nicholas Brunacci OP [1240–1322], who had been a student of Thomas Aquinas at the Santa Sabina studium in Rome, later at Paris,[46] and of Albert the Great at the Cologne studium.[47] Brunacci became lector at the Santa Sabina studium, forerunner of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, and later served in the papal curia.[48]

In 1315, Florence was forced by Uguccione della Faggiuola (the military officer controlling the town) to grant an amnesty to those in exile, including Dante. But for this, Florence required public penance in addition to payment of a high fine. Dante refused, preferring to remain in exile. When Uguccione defeated Florence, Dante's death sentence was commuted to house arrest, on condition that he go to Florence to swear he would never enter the town again. He refused to go, and his death sentence was confirmed and extended to his sons.[49] Despite this, he still hoped late in life that he might be invited back to Florence on honorable terms, particularly in praise of his poetry.[50]

Death and burial

_-_Facade.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Dante's final days were spent in Ravenna, where he had been invited to stay in the city in 1318 by its prince, Guido II da Polenta. Dante died in Ravenna on 14 September 1321, aged about 56, of quartan malaria contracted while returning from a diplomatic mission to the Republic of Venice. He was attended by his three children, and possibly by Gemma Donati, and by friends and admirers he had in the city.[51] He was buried in Ravenna at the Church of San Pier Maggiore (later called Basilica di San Francesco). Bernardo Bembo, praetor of Venice, erected a tomb for him in 1483.[52][53]

On the grave, a verse of Bernardo Canaccio, a friend of Dante, is dedicated to Florence:

parvi Florentia mater amoris |

Florence, mother of little love |

In 1329, Bertrand du Pouget, Cardinal and nephew of Pope John XXII, classified Dante's Monarchia as heretical and sought to have his bones burned at the stake. Ostasio I da Polenta and Pino della Tosa, allies of Pouget, interceded to prevent the destruction of Dante's remains.[54]

Florence eventually came to regret having exiled Dante. The city made repeated requests for the return of his remains. The custodians of the body in Ravenna refused, at one point going so far as to conceal the bones in a false wall of the monastery. Florence built a tomb for Dante in 1829, in the Basilica of Santa Croce. That tomb has been empty ever since, with Dante's body remaining in Ravenna. The front of his tomb in Florence reads Onorate l'altissimo poeta — which roughly translates as "Honor the most exalted poet" and is a quote from the fourth canto of the Inferno.[55]

In 1945, the fascist government discussed bringing Dante's remains to the Valtellina Redoubt, the Alpine valley in which the regime intended to make its last stand against the Allies. The case was made that "the greatest symbol of Italianness" should be present at fascism's "heroic" end.[56]

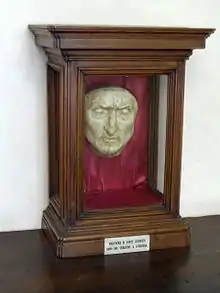

A copy of Dante's so-called death mask has been displayed since 1911 in the Palazzo Vecchio; scholars today believe it is not a true death mask and was probably carved in 1483, perhaps by Pietro and Tullio Lombardo.[57][58]

Legacy

The first formal biography of Dante was the Vita di Dante (also known as Trattatello in laude di Dante), written after 1348 by Giovanni Boccaccio.[59] Although several statements and episodes of it have been deemed unreliable on the basis of modern research, an earlier account of Dante's life and works had been included in the Nuova Cronica of the Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani.[60]

Some 16th-century English Protestants, such as John Bale and John Foxe, argued that Dante was a proto-Protestant because of his opposition to the pope.[61][62]

The 19th century saw a "Dante revival", a product of the medieval revival, which was itself an important aspect of Romanticism.[63] Thomas Carlyle profiled him in "The Hero as Poet", the third lecture in On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History (1841): "He is world-great not because he is worldwide, but because he is world-deep. . . . Dante is the spokesman of the Middle Ages; the Thought they lived by stands here, in everlasting music."[64] Leigh Hunt, Henry Francis Cary and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were among Dante's translators of the era.

_18_-_Dante_Alighieri_Statue.jpg.webp)

Italy's first dreadnought battleship was completed in 1913 and named Dante Alighieri in honor of him.[65]

On 30 April 1921, in honor of the 600th anniversary of Dante's death, Pope Benedict XV promulgated an encyclical named In praeclara summorum, naming Dante as one "of the many celebrated geniuses of whom the Catholic faith can boast" and the "pride and glory of humanity".[66]

On 7 December 1965, Pope Paul VI promulgated the Latin motu proprio titled Altissimi cantus, which was dedicated to Dante's figure and poetry.[67] In that year, the pope also donated a golden iron Greek Cross to Dante's burial site in Ravenna, in occasion of the 700th anniversary of his birth.[68][69] The same cross was blessed by Pope Francis in October 2020.[70]

.jpg.webp)

In 2007, a reconstruction of Dante's face was undertaken in a collaborative project. Artists from the University of Pisa and forensic engineers at the University of Bologna at Forlì constructed the model, portraying Dante's features as somewhat different from what was once thought.[71][72]

In 2008, the Municipality of Florence officially apologized for expelling Dante 700 years earlier.[73][74][75][76]

A celebration was held in 2015 at Italy's Senate of the Republic for the 750th anniversary of Dante's birth. It included a commemoration from Pope Francis, who also issued the apostolic letter Cando lucis aeternae in honor of the anniversary.[77][78]

In May 2021, a symbolic re-trial of Dante Alighieri was held virtually in Florence to posthumously clear his name.[79]

Works

Overview

Most of Dante's literary work was composed after his exile in 1301. La Vita Nuova ("The New Life") is the only major work that predates it; it is a collection of lyric poems (sonnets and songs) with commentary in prose, ostensibly intended to be circulated in manuscript form, as was customary for such poems.[80] It also contains, or constructs, the story of his love for Beatrice Portinari, who later served as the ultimate symbol of salvation in the Comedy, a function already indicated in the final pages of the Vita Nuova. The work contains many of Dante's love poems in Tuscan, which was not unprecedented; the vernacular had been regularly used for lyric works before, during all the thirteenth century. However, Dante's commentary on his own work is also in the vernacular—both in the Vita Nuova and in the Convivio—instead of the Latin that was almost universally used.[81]

The Divine Comedy describes Dante's journey through Hell (Inferno), Purgatory (Purgatorio), and Paradise (Paradiso); he is first guided by the Roman poet Virgil and then by Beatrice. Of the books, Purgatorio is arguably the most lyrical of the three, referring to more contemporary poets and artists than Inferno; Paradiso is the most heavily theological, and the one in which, many scholars have argued, the Divine Comedy's most beautiful and mystic passages appear.[82][83]

_-_WGA06423.jpg.webp)

With its seriousness of purpose, its literary stature and the range—both stylistic and thematic—of its content, the Comedy soon became a cornerstone in the evolution of Italian as an established literary language. Dante was more aware than most early Italian writers of the variety of Italian dialects and of the need to create a literature and a unified literary language beyond the limits of Latin writing at the time; in that sense, he is a forerunner of the Renaissance, with its effort to create vernacular literature in competition with earlier classical writers. Dante's in-depth knowledge (within the limits of his time) of Roman antiquity, and his evident admiration for some aspects of pagan Rome, also point forward to the 15th century. Ironically, while he was widely honored in the centuries after his death, the Comedy slipped out of fashion among men of letters: too medieval, too rough and tragic, and not stylistically refined in the respects that the high and late Renaissance came to demand of literature.

He wrote the Comedy in a language he called "Italian", in some sense an amalgamated literary language predominantly based on the regional dialect of Tuscany, but with some elements of Latin and other regional dialects.[84] He deliberately aimed to reach a readership throughout Italy including laymen, clergymen and other poets. By creating a poem of epic structure and philosophic purpose, he established that the Italian language was suitable for the highest sort of expression. In French, Italian is sometimes nicknamed la langue de Dante. Publishing in the vernacular language marked Dante as one of the first in Roman Catholic Western Europe (among others such as Geoffrey Chaucer and Giovanni Boccaccio) to break free from standards of publishing in only Latin (the language of liturgy, history and scholarship in general, but often also of lyric poetry). This break set a precedent and allowed more literature to be published for a wider audience, setting the stage for greater levels of literacy in the future. However, unlike Boccaccio, Milton or Ariosto, Dante did not really become an author read across Europe until the Romantic era. To the Romantics, Dante, like Homer and Shakespeare, was a prime example of the "original genius" who set his own rules, created persons of overpowering stature and depth, and went far beyond any imitation of the patterns of earlier masters; and who, in turn, could not truly be imitated. Throughout the 19th century, Dante's reputation grew and solidified; and by 1865, the 600th anniversary of his birth, he had become established as one of the greatest literary icons of the Western world.[85]

New readers often wonder how such a serious work may be called a "comedy". In the classical sense the word comedy refers to works that reflect belief in an ordered universe, in which events tend toward not only a happy or amusing ending but one influenced by a Providential will that orders all things to an ultimate good. By this meaning of the word, as Dante himself allegedly wrote in a letter to Cangrande I della Scala, the progression of the pilgrimage from Hell to Paradise is the paradigmatic expression of comedy, since the work begins with the pilgrim's moral confusion and ends with the vision of God.[86]

A number of other works are credited to Dante. Convivio ("The Banquet")[87] is a collection of his longest poems with an (unfinished) allegorical commentary. Monarchia ("Monarchy")[88] is a summary treatise of political philosophy in Latin which was condemned and burned after Dante's death[89][90] by the Papal Legate Bertrando del Poggetto; it argues for the necessity of a universal or global monarchy to establish universal peace in this life, and this monarchy's relationship to the Roman Catholic Church as guide to eternal peace. De vulgari eloquentia ("On the Eloquence in the Vernacular")[91] is a treatise on vernacular literature, partly inspired by the Razos de trobar of Raimon Vidal de Bezaudun.[92][93] Quaestio de aqua et terra ("A Question of the Water and of the Land") is a theological work discussing the arrangement of Earth's dry land and ocean. The Eclogues are two poems addressed to the poet Giovanni del Virgilio. Dante is also sometimes credited with writing Il Fiore ("The Flower"), a series of sonnets summarizing Le Roman de la Rose, and Detto d'Amore ("Tale of Love"), a short narrative poem also based on Le Roman de la Rose. These would be the earliest, and most novice, of his known works.[94] Le Rime is a posthumous collection of miscellaneous poems.

List of works

The major works of Dante's are the following.[95][96]

- Il Fiore and Detto d'Amore ("The Flower" and "Tale of Love", 1283–87)

- La Vita Nuova ("The New Life", 1294)

- De vulgari eloquentia ("On the Eloquence in the Vernacular", 1302–05)

- Convivio ("The Banquet", 1307)

- Monarchia ("Monarchy", 1313)

- Divina Commedia ("Divine Comedy", 1320)

- Eclogues (1320)

- Quaestio de aqua et terra ("A Question of the Water and of the Land", 1320)

- Le Rime ("The Rhymes")

.jpg.webp) Illustration for Purgatorio (of The Divine Comedy) by Gustave Doré

Illustration for Purgatorio (of The Divine Comedy) by Gustave Doré Illustration for Paradiso (of The Divine Comedy) by Gustave Doré

Illustration for Paradiso (of The Divine Comedy) by Gustave Doré_II.jpg.webp) Illustration for Paradiso (of The Divine Comedy) by Gustave Doré

Illustration for Paradiso (of The Divine Comedy) by Gustave Doré

Notes

- The name 'Dante' is understood to be a hypocorism of the name 'Durante', though no document known to survive from Dante's lifetime refers to him as ‘Durante’ (including his own writings). A document prepared for Dante's son Jacopo refers to "Durante, often called Dante". He may have been named for his maternal grandfather Durante degli Abati.[2]

- Though an Italian nation state had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term Italian (italus) had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity.[6]

Citations

- His birth date is listed as "probably in the end of May" by Robert Hollander in "Dante" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, volume 4. According to Giovanni Boccaccio, the poet said he was born in May. See "Alighieri, Dante" in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani.

- Gorni, Guglielmo (2009). "Nascita e anagrafe di Dante". Dante: storia di un visionario. Rome: Gius. Laterza & Figli. ISBN 9788858101742.

- "Dante". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Dante" (US) and "Dante". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020.

- "Dante". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Pliny the Elder, Letters 9.23.

- Wetherbee, Winthrop; Aleksander, Jason (30 April 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Hutton, Edward (1910). Giovanni Boccaccio, a Biographical Study. p. 273.

- Bloom, Harold (1994). The Western Canon. Riverhead Books. ISBN 9781573225144.

- Shaw, Prue (2014). Reading Dante: From Here to Eternity. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. Introduction. ISBN 978-0-87140-742-9.

- Quinones, Ricardo J. (9 May 2023). "Dante Alighieri – Biography, Poems, & Facts". Britannica.

- Matheson, Lister M. (2012). Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints. Greenwood Pub Group. p. 244.

- Haller, Elizabeth K. (2012). "Dante Alighieri". In Matheson, Lister M. (ed.). Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-313-34080-2.

- Murray, Charles A. (2003). Human accomplishment: the pursuit of excellence in the arts and sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950 (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-019247-1. OCLC 52047270.

- Barański, Zygmunt G.; Gilson, Simon, eds. (2018). The Cambridge Companion to Dante's 'Commedia'. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9781108421294.

- Santagata 2016, p. 6.

- Gombrich, E. H. (1979). "Giotto's Portrait of Dante?". The Burlington Magazine. 121 (917): 471–483 – via JSTOR.

- Chimenz, Siro A. (1960). "Alighieri, Dante". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 2. Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- His birth date is listed as "probably in the end of May" by Robert Hollander in "Dante" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, volume 4. According to Giovanni Boccaccio, the poet said he was born in May. See "Alighieri, Dante" in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani.

- Chimenz, S.A (2014). Alighieri, Dante. Bibcode:2014bea..book...56. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Santagata, Marco (2012). Dante: Il romanzo della sua vita. Milan: Mondadori. p. 21. ISBN 978-88-04-62026-6.

- florence Inferno

- Alighieri, Dante (2013). Delphi Complete Works of Dante Alighieri. Vol. 6 (Illustrated ed.). Delphi Classics. ISBN 978-1-909496-19-4.

- Alighieri, Dante (1904). Philip Henry Wicksteed, Herman Oelsner (ed.). The Paradiso of Dante Alighieri (fifth ed.). J.M. Dent and Company. p. 129.

- Davenport, John (2005). Dante: Poet, Author, and Proud Florentine. Infobase Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4381-0415-7. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- di Serego Alighieri, Sperello; Capaccioli, Massimo (2022). The Sun and the other Stars of Dante Alighieri. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. p. 48. ISBN 9789811246227.

- "Dante Alighieri". poets.org. Academy of American Poets. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Nilsen, Alleen Pace; Don L.F. Nilsen (2007). Names and Naming in Young Adult Literature. Scarecrow Studies in Young Adult Literature. Vol. 27. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-8108-6685-0.

- Ruud, Jay (2008). Critical Companion to Dante. Infobase Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4381-0841-4.

- "Guelphs and Ghibellines". Dante Alighieri Society of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Santagata 2016, p. 62.

- Dino Compagni, Cronica delle cose occorrenti ne' tempi suoi

- Harrison 2015, pp. 36–37.

- Harrison 2015, p. 36.

- Moore, Malcolm (17 June 2008). "Dante's infernal crimes forgiven". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- Raffa 2020, p. 24.

- Santagata 2016, p. 208.

- Santagata 2016, p. 249.

- Latham, Charles S.; Carpenter, George R. (1891). A Translation of Dante’s Eleven Letters. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. pp. 269–282.

- Carroll, John S. (1903). Exiles of Eternity: An Exposition of Dante's Inferno. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. xlviii–l.

- Wickstool, Philip Henry (1903). The Convivio of Dante Alighieri. London : J. M. Dent and co. p. 5.

And in that I spoke before entrance on the prime of manhood, and in this when I had already passed the same.

- See Bookrags.com and Tigerstedt, E.N. 1967, Dante; Tiden Mannen Verket (Dante; The Age, the Man, the Work), Bonniers, Stockholm, 1967.

- Bertolo, Fabio M. (2003). "L'Officiolum ritrovato di Francesco da Barberino". Spolia – Journal of Medieval Studies. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Santagata 2016, p. 339.

- "Cangrande della Scala – "Da molte stelle mi vien questa luce"" [Cangrande della Scala – "This light comes to me from many stars"]. dantealighieri.tk (in Italian). Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Le famiglie Brunacci". Brunacci.it. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Garin, Eugenio (2008). History of Italian Philosophy: VIBS. Rodopi. p. 85. ISBN 978-90-420-2321-5. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Frater Nicolaus Brunatii [† 1322] sacerdos et predicator gratiosus, fuit lector castellanus, arectinus, perusinus, urbevetanus et romanus apud Sanctam Sabinam tempore quo papa erat in Urbe, viterbiensis et florentinus in studio generali legens ibidem annis tribus (Cr Pg 37v). Cuius sollicita procuratione conventus perusinus meruit habere gratiam a summo pontifice papa Benedicto XI ecclesiam scilicet et parrochiam Sancti Stephani tempore quo [maggio 13041 ipse prior actu in Perusio erat (Cr Pg 38r)". E-theca.net. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Burdeau, Cain (21 May 2021). "Dante Gets a Bit of Justice, 700 Years After His Death". courthousenews.com. Courthouse News Service. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Santagata 2016, p. 333–334.

- Raffa 2020, pp. 23–24, 27, 28–30.

- Pirro, Deirdre (10 April 2017). "Dante: the battle of the bones". The Florentine.

- "Italy Magazine, Dante's Tomb". italymagazine.com. 31 October 2017.

- Raffa 2020, p. 38.

- Phelan, Jessica (4 September 2019). "Dante's last laugh: Why Italy's national poet isn't buried where you think he is". The Local Italy.

- Raffa 2020, pp. 244–245.

- "Dante death mask". florenceinferno.com. July 2013.

- "10 Controversial Death Masks Of Famous People". listverse.com. 21 October 2014.

- "Dante Alighieri". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Vauchez, André; Dobson, Richard Barrie; Lapidge, Michael (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 1517.; Caesar, Michael (1989). Dante, the Critical Heritage, 1314(?)–1870. London: Routledge. p. xi.

- Boswell, Jackson Campbell (1999). Dante's Fame in England: References in Printed British Books, 1477–1640. Newark: University of Delaware Press. p. xv. ISBN 0-87413-605-9.

After John Foxe's enormously influential Ecclesiastical History Contayning the Actes and Monumentes was published (1570), Dante's role as a proto-Protestant was sealed.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Foxe's Book of Martyrs". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- "19th Century: A History of English Romanticism by Henry Augustin Beers: Ch. 3: Keats, Leigh Hunt, and the Dante Revival". www.online-literature.com. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1841). "Lecture III. The Hero as Poet. Dante: Shakspeare.". On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History.

- "Italian dreadnought battleship Dante Alighieri (1910)". naval encyclopedia. 21 July 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "In praeclara summorum: Encyclical of Pope Benedict XV on Dante". The Holy See. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "Altissimi cantus". Vatican State (in Latin and Italian). Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "Dante Alighieri's tomb". Ravenna. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- "Pope Francis: The fascination of God makes its powerful attraction felt". Vatican News. 10 October 2020. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Pietracci, Sara (11 October 2020). "Papa Francesco annuncia alla delegazione ravennate la preparazione di un documento pontificio su Dante" [Pope Francis says to the delegation from Ravenna he his working to a pontifical document related to Dante] (in Italian). Ravenna. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- Pullella, Philip (12 January 2007). "Dante gets posthumous nose job – 700 years on". Statesman. Reuters. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- Benazzi, S (2009). "The Face of the Poet Dante Alighieri, Reconstructed by Virtual Modeling and Forensic Anthropology Techniques". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (2): 278–283. Bibcode:2009JArSc..36..278B. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.006.

- "Florence sorry for banishing Dante". UPI.

- Israely, Jeff (31 July 2008). "A City's Infernal Dante Dispute". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Duff, Mark (18 June 2008). "Florence 'to revoke Dante exile'". BBC.

- "Firenze riabilita Dante Alighieri: L'iniziativa a 700 anni dall'esilio". La Repubblica. 30 March 2008.

- "Messaggio del Santo Padre al Presidente del Pontificio Consiglio della Cultura in occasione della celebrazione del 750° anniversario della nascita di Dante Alighieri". Press.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "Translator". Microsofttranslator.com. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "Florence hosts 're-trial' of Dante, convicted and banished in 1302". DW. 21 May 2021.

- "New Life". Dante online. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Scott, John (1995). "The Unfinished 'Convivio' as a Pathway to the 'Comedy'". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society. 113 (113): 31–56. JSTOR 40166505 – via JSTOR.

- Kalkavage, Peter (10 August 2014). "In the Heaven of Knowing: Dante's Paradiso". theimaginativeconservative.org. The Imaginative Conservative. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Falconburg, Darrell. "The Way of Beauty in Dante". dappledthings.org. Dappled Things. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- Dante at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "An Italian Icon". fu-berlin.de. Freie Universität Berlin. 14 September 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- "Epistle to Cangrande Updated". www.dantesociety.org. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- "Banquet". Dante online. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- "Monarchia". Dante online. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Anthony K. Cassell The Monarchia Controversy. Monarchia stayed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum from its inception until 1881.

- Giuseppe Cappelli, La divina commedia di Dante Alighieri, in Italian.

- "De vulgari Eloquentia". Dante online. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Ewert, A. (1940). "Dante's Theory of Language". The Modern Language Review. 35 (3): 355–366. doi:10.2307/3716632. JSTOR 3716632.

- Faidit, Uc; Vidal, Raimon; Guessard, François (1858). Grammaires provençales de Hugues Faidit et de Raymond Vidal de Besaudun (XIIIe siècle) (2nd ed.). Paris: A. Franck.

- Lansing, Richard (2000). The Dante Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 299, 334, 379, 734. ISBN 0815316593.

- Wilkins, Ernest H. (1920). "An Introductory Dante Bibliography". Modern Philology. 17 (11): 623–632. doi:10.1086/387304. hdl:2027/mdp.39015033478622. JSTOR 432861. S2CID 161197863.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France {BnF Data}. "Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)".

References

- Allitt, John Stewart (2011). Dante, il pellegrino (in Italian). Villa di Serio (BG): Edizioni Villadiseriane. ISBN 978-88-96199-80-0.

- Anderson, William (1980). Dante the Maker. Routledge Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-0322-5.

- Barolini, Teodolinda (ed.). Dante's Lyric Poetry: Poems of Youth and of the 'Vita Nuova'. University of Toronto Press, 2014.

- Gardner, Edmund Garratt (1921). Dante. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 690699123. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Harrison, Robert (19 February 2015). "Dante on Trial". NY Review of Books. pp. 36–37.

- Hede, Jesper (2007). Reading Dante: The Pursuit of Meaning. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2196-2.

- Miles, Thomas (2008). "Dante: Tours of Hell: Mapping the Landscape of Sin and Despair". In Stewart, Jon (ed.). Kierkegaard and the Patristic and Medieval Traditions. Ashgate. pp. 223–236. ISBN 978-0-7546-6391-1.

- Raffa, Guy P. (2009). The Complete Danteworlds: A Reader's Guide to the Divine Comedy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-70270-4.

- Raffa, Guy P. (2020). Dante's Bones: How a Poet Invented Italy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98083-9.

- Santagata, Marco (2016). Dante: The Story of His Life. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674504868.

- Scartazzini, Giovanni Andrea (1874–1890). La Divina Commedia riveduta e commentata (4 volumes). OCLC 558999245.

- Scartazzini, Giovanni Andrea (1896–1898). Enciclopedia dantesca: dizionario critico e ragionato di quanto concerne la vita e le opere di Dante Alighieri (2 volumes). OCLC 12202483.

- Scott, John A. (1996). Dante's Political Purgatory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-585-12724-8.

- Seung, T.K. (1962). The Fragile Leaves of the Sibyl: Dante's Master Plan. Westminster, MD: Newman Press. OCLC 1426455.

- Toynbee, Paget (1898). A Dictionary of the Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante. London: The Clarendon Press. OCLC 343895. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Whiting, Mary Bradford (1922). Dante the Man and the Poet. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. OCLC 224789.

- Guénon, René (1925). The Esoterism of Dante, trans. by C.B. Berhill, in the Perennial Wisdom Series. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis et Universalis, 1996. viii, 72 p. N.B.: Originally published in French, entitled L'Esoterisme de Danté, in 1925. ISBN 0-900588-02-0

External links

- Works by Dante Alighieri in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Dante Alighieri at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Dante Alighieri at Internet Archive

- Works by Dante Alighieri at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Dante Alighieri at Curlie

- Works by Dante Alighieri at One More Library (Works in English, Italian, Latin, Arabic, German, French and Spanish)

- Wetherbee, Winthrop. "Dante Alighieri". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Dante Museum in Florence: his life, his books and a history & literature blog about Dante

- The World of Dante multimedia, texts, maps, gallery, searchable database, music, teacher resources, timeline

- The Princeton Dante Project Archived 3 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine texts and multimedia

- The Dartmouth Dante Project searchable database of commentary

- Dante Online manuscripts of works, images and text transcripts by Società Dantesca Italiana

- Digital Dante – Divine Comedy with commentary, other works, scholars on Dante

- Open Yale Course on Dante by Yale University

- DanteSources project about Dante's primary sources developed by ISTI-CNR and the University of Pisa

- Works Italian and Latin texts, concordances and frequency lists by IntraText

- Dante Today Archived 11 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine citings and sightings of Dante in contemporary culture

- Bibliotheca Dantesca journal dedicated to Dante and his reception

- Edmund Garratt Gardner (1908). "Dante Alighieri". In Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Arthur John Butler (1911). "Dante". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 7. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 810–817.

- Dante Collection at University College London (c. 3000 volumes of works by and about Dante)

.JPG.webp)