Danny Driscoll

Daniel Driscoll also known by his alias George Wallace (1855 – January 23, 1888) was an American criminal and co-leader of the Whyos Gang with Danny Lyons. The two held joint control over the street gang following the execution of Mike McGloin in 1883; however, both men were executed for separate murders only months apart from each other. They were the last powerful leaders of the organization and, following their downfall, the Whyos were eventually replaced by the Eastman and Five Points Gangs.

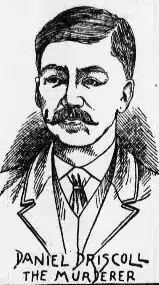

Danny Driscoll | |

|---|---|

Danny Driscoll in the New York World newspaper, January 23, 1888 the day of his execution | |

| Born | Daniel Driscoll 1855 Five Points, Manhattan, New York City, United States |

| Died | January 23, 1888 (aged 33) Tombs Prison, Manhattan, New York City |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality | Irish-American |

| Other names | George Wallace |

| Occupation | Criminal |

| Known for | Co-leader of the Whyos with Danny Lyons; convicted of the murder of Beezy Garrity. |

| Spouse | Mary Driscoll |

His arrest for the murder of well-known Five Points debutante Bridget "Beezy" Garrity during 1886 was followed by one of the most publicized trials of New York's history.[1][2]

Early life

Growing up in a Five Points tenement district, Daniel Driscoll amassed a considerable criminal record by the time he had become a young adult. He was arrested 25 times for transgressions that frequently involved stabbings and shootings, and he served a combined 16 years in both the New York State Penitentiary and New York State Prison. He also acted as a fagin training local youths to pickpocket.[3] In 1882, Driscoll was arrested for grand larceny but escaped from The Tombs when, while being transported in a Black Maria, he switched names with a man arrested for public drunkenness. Upon their arrival, Driscoll simply paid a $10 fine and walked out of the prison.[4]

Whyos Gang

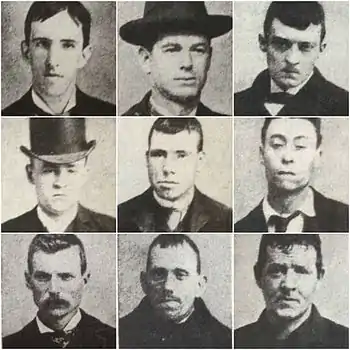

Top row left to right: Baboon Connolly, Josh Hines, Bull Hurley

Middle row left to right: Clops Connelly, Dorsey Doyle, Googy Corcaran

Bottom row left to right: Mike Lloyd, Piker Ryan, Red Rocks Farrell

He had become a prominent member of the Whyos by the early 1880s, at the time the most dominant street gang in the city, and became leader of the organization with Danny Lyons following the execution of longtime leader Mike McGloin in 1883. In 1885, he was forced to leave the city and spent some time on the West Coast before returning to New York in May 1886.[3]

Murder of Beezy Garrity

On June 26, 1886, Driscoll rode by coach to a three-story brick house on the north side of Hester Street. According to traditional accounts, Driscoll had been approached by Bridget "Beezy" Garrity, who claimed she had been cheated by the owner of a panel house operating within the Whyos territory.[2] Although he had been barred from the property of the resident "bouncer" John McCarty (or McCarthy), with whom he had been involved in a long-standing feud, he arrived at the house with Garrity at around 4:00 am. He sent Garrity ahead of him so that she could be let in by McCarty and then let Driscoll in afterwards. However, after Garrity was let in to the front parlor, McCarty spotted Driscoll and attempted to close the door. Driscoll was able to block the door open with his arm and, during the struggle, McCarty drew his revolver.[3]

What happened after this point is unclear. According to news accounts, Garrity attempted to stop McCarty from using his weapon. Alerted by her cries, Driscoll took his own revolver out and attempted to shoot McCarty by aiming at him from between the edge of the door and the doorjamb. His first shot hit the wall opposite McCarty. He then tried, unsuccessfully, to fire between the inner door and the doorjamb. Both McCarty and Garrity ran from the area at this point, with Garrity going to the back room. As Driscoll entered the darkened hallway, Garrity ran out from a door leading from the back room. Driscoll apparently thought that this was McCarty and fired into the dark, hitting Garrity in the abdomen.[2][3]

He then attempted to flee the area. Driscoll was pursued by police officers then arriving at the house. Several warning shots were fired, but he did not stop. Driscoll was chased by police before disappearing into the open door of a Baxter Street tenement where his mother lived. An extensive search of the area was conducted and he was eventually found by police hiding behind the door of an unoccupied apartment in the next building. He denied shooting Garrity and had no weapon on him but was taken into custody and held at the Mulberry Street police station.[3]

Garrity was taken to St. Vincent's Hospital, where she died that afternoon. Before she died, she identified McCarty as her attacker. McCarty was initially arrested; however he denied he had fired a shot and showed his revolver which was still loaded and not fired. This claim was later dismissed believing that she was attempting to protect her supposed lover.[3]

Murder trial

Fifty members of the Whyos were in the courtroom at the time of his arraignment, however they were forced to leave by the presiding judge Justice Patterson.[3] On the morning of June 28, Driscoll and McCarty were taken to the Tombs Police Court. They appeared friendly and were talking for some time prior to the proceedings. Once court was in session however, both men blamed each other for Garrity's death.

When McCarty testified, he claimed that he had been sitting in his room when Garrity, a woman he claimed had never seen before, entered his home with Driscoll following closely behind her. He closed the door behind her and then Driscoll firing his pistol through an opening just below the upper hinge. Believing that Driscoll might enter the house another way and shoot him from behind, McCarty then jumped from a window in an adjoining room into the yard. He had heard a second shot, but did not return to the house until he had seen Driscoll being arrested by police who had arrived by that time. Entering his room, he discovered Garrity lying on his bed and who accused him of having shot her. Upon hearing this, he immediately handed his pistol to an officer, Peter Monahan, who found that the gun was fully loaded and no shots had been fired. Monahan would corroborate this story during the trial.

Driscoll interrupted court proceedings claiming that he himself was unarmed at the time of the incident and that McCarty was the only one who could have shot Garrity. Driscoll then addressed the court.

I've got a bad name with the police and they say "give a dog a bad name and we'll hang him". McCarty's got lots of money and I am without a cent. He's trying to put the blame on me. I'll show you up in your true light when the time comes, my good friend.

Carrie Wilson, a local Chrystie Street resident, testified that she was in the building at the time of the shooting and that she had seen Driscoll and Garrity arrive in a coach with another man and woman. She further claimed that she had seen Driscoll fire two shots through the door and, after the second shot, a woman fell. John Green and Emmanuel Devoss, both local residents, said they were in the back room when they also heard shots fired.[5]

On the last day of the trial, a doctor from St. Vincent's Hospital made a surprise appearance and testified that Garrity told him McCarthy was the man who shot her. Driscoll's lawyer, Bill Howe, was also able to weaken the credibility of the witnesses testimony; however, Driscoll was found guilty of first degree murder on September 30, 1886.[6]

_pg501_THE_TOMBS._THE_PLACE_OF_DETENTION_FOR_CRIMINALS_AWAITING_TRIAL_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Imprisonment and execution

Days before his conviction, Driscoll was moved to "Murderer's Row" after it was discovered by the warden that Driscoll had been attempting to tunnel out of his cell.[4] He was guarded by Inspector Williams and 75 police officers for the remainder of his time in The Tombs. He was allowed to see his relatives the day before his execution and, in his last words to his wife, Driscoll said "I die happy. Take good care of yourself, Mary. I'll pray for you in heaven." Maintaining his innocence, he continued to make criminal charges against Warden Walsh. These charges were disputed among a number of prison guards who signed a petition in his defense.[7]

On the morning of January 23, 1888, Driscoll was brought to the yard of The Tombs Prison, where he was publicly hanged.[2] His execution was witnessed by Sheriff Grant and his deputy, Fathers Pendergrast and Gilenas, and fourteen reporters. Also present was Commodore Elbridge T. Gerry, who attended the execution to report that the execution had been conducted in a humane and just manner.[8]

References

- Asbury, Herbert. The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the New York Underworld. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. (211-212) ISBN 1-56025-275-8

- English, T.J. Paddy Whacked: The Untold Story of the Irish American Gangster. New York: HarperCollins, 2005. (pg. 33, 36-38) ISBN 0-06-059002-5

- "A Struggle in the Dark; Firing at an Enemy and Killing a Friend, How Lizzie Garrity was Shot and Killed by Daniel Driscoll During an Early Morning Quarrel" New York Times. 27 Jun 1886.

- "Driscoll Plans An Escape.; He Is Detected And Removed To Another Cell". New York Times. 29 Sep 1886

- "Lizzie Garrity's Death; Daniel Driscoll and John McCarty Held For Examination" New York Times. 28 Jun 1886.

- "Driscoll Found Guilty.; The Jury Reaches A Decision In A Short Half Hour". New York Times. 01 Oct 1886

- "Driscoll's Last Day". New York Times. 23 Jan 1888.

- "Daniel Driscoll Hanged". New York Times. 24 Jan 1888.

Further reading

- Browning, Frank and John Gerassi. The American Way of Crime: From Salem to Watergate, a Stunning New Perspective on Crime in America. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1980.

- Kohn, George C. Dictionary of Culprits and Criminals. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1986.

- Moss, Frank. The American Metropolis from Knickerbocker Days to the Present Time. London: The Authors' Syndicate, 1897.

- Riis, Jacob A. How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1890.

- Rovere, Richard H. The Magnificent Shysters: The True and Scandalous History of Howe & Hummel. New York: Grosset & Dunlap Publishers, 1947.

- Russell, Charles Edward. Bare Hands and Stone Walls: Some Recollections of a Side-line Reformer. York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933.

- Still, Charles E. Styles in Crimes: With 21 Illustrations in Doubletone. J.B. Lippincott, 1938.