Politics of Denmark

The politics of Denmark take place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democracy, a constitutional monarchy and a decentralised unitary state in which the monarch of Denmark, Queen Margrethe II, is the head of state.[1] Denmark is a nation state. Danish politics and governance are characterized by a common striving for broad consensus on important issues, within both the political community and society as a whole.

Politics of Denmark Dansk politik | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polity type | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Constitution | Constitution of Denmark |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | Parliament |

| Type | Unicameral |

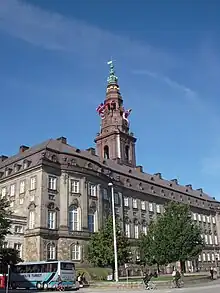

| Meeting place | Christiansborg Palace |

| Presiding officer | Søren Gade, Speaker of the Parliament |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | Monarch |

| Currently | Margrethe II |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Mette Frederiksen |

| Appointer | Monarch |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Cabinet of Denmark |

| Current cabinet | Frederiksen II Cabinet |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Ministries | 18 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | General Judicial System |

| Courts | Courts of Denmark |

| Supreme Court | |

| Chief judge | Thomas Rørdam |

|

|---|

Executive power is exercised by the cabinet of Denmark (commonly known as "the Government", Danish: regeringen), presided over by the Prime Minister (statsminister) who is first among equals. Legislative power is exercised by the Folketing, the unicameral parliament, and secondarily by the Cabinet. Members of the judiciary are nominated by the executive (conventionally by recommendation of the judiciary itself), formally appointed by the monarch and employed until retirement.

Denmark has a multi-party system, with two large parties, and several other small but significant parties. No single party has held an absolute majority in the Folketing since the beginning of the 20th century.[2] Thirteen parties have ballot access for the 2019 Danish general election, three of which did not contest 2015 general election. Since only four post-war coalition governments have enjoyed a majority, government bills rarely become law without negotiations and compromise with both supporting and opposition parties. Hence, the Folketing tends to be more powerful than legislatures in other EU countries. The Constitution does not grant the judiciary power of judicial review of legislation; however, the courts have asserted this power with the consent of the other branches of government. Since there are no constitutional or administrative courts, the Supreme Court also deals with constitutional matters.

On many issues the political parties tend to opt for co-operation, and the Danish state welfare model receives broad parliamentary support. This ensures a focus on public-sector efficiency and devolved responsibilities of local government on regional and municipal levels.

The degree of transparency and accountability is reflected in the public's high level of satisfaction with the political institutions, while Denmark is also regularly considered one of the least corrupt countries in the world by international organizations.[3] The Economist Intelligence Unit rated Denmark as "full democracy" in 2016.[4]

Monarchy

Queen Margrethe II of Denmark (born 16 April 1940) has ruled as Queen Regnant and head of state since 14 January 1972.[5] In accordance with the Danish Constitution the monarch as head of state is the theoretical source of all executive and legislative power.[6] However, since the introduction of parliamentary sovereignty in 1901, a de facto separation of powers has been in effect.[7]

The text of the Danish constitution dates back to 1849. Therefore, it has been interpreted by jurists to suit modern conditions. In a formal sense, the monarch retains the ability to deny giving a bill royal assent. In order for a bill to become law, a royal signature and a countersignature by a government minister are required.[6] The monarch also chooses and dismisses the Prime Minister, although in modern times a dismissal would cause a constitutional crisis. On 28 March 1920, King Christian X was the last monarch to exercise the power of dismissal, sparking the 1920 Easter Crisis. All royal powers called royal prerogative, such as patronage to appoint ministers and the ability to declare war and make peace, are exercised by the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, with the formal consent of the Queen. When a new government is to be formed, the monarch calls the party leaders to a conference of deliberation (known as a "dronningerunde", meaning "queen's round"), where the latter advise the monarch. On the basis of the advice, the monarch then appoints the party leader who commands a majority of recommendation to lead negotiations for forming a new government.[6]

According to the principles of constitutional monarchy, the monarch's role is largely ceremonial today, restricted in his or her exercise of power by the convention of parliamentary democracy and the separation of powers. However, the monarch does continue to exercise three rights: the right to be consulted; the right to advise; and the right to warn. Pursuant to these ideals, the Prime Minister and the Cabinet attend the regular meeting of the Council of State.[8]

Political parties

Denmark has a multi-party system. Ten parties are represented in parliament, while an additional three were qualified to contest the most recent 2019 general election but did not win any seats. The four oldest, and in history most influential, parties are the Conservative People's Party, the Social Democrats, Venstre (the name literally means "Left", but it is a right-wing liberal-conservative party) and the Social Liberal Party. However, demographics have been in favour of newer parties (such as the national conservative far-right Danish People's Party and the far-left Red-Green Alliance).

No two parties have exactly the same organization. It is however common for a party to have an annual convention which approves manifestos and elects party chairmen, a board of leaders, an assembly of representatives, and a number of local branches with their own organization. In most cases the party members in parliament form their own group with autonomy to develop and promote party politics in parliament and between elections. Parties also have youth wings to promote engagement with the party among young people, such as Social Democratic Youth, Young Liberals, and Radikal Ungdom.

Political blocs

Though coined in 1994 by then leader of Venstre Uffe Ellemann-Jensen, the terms red bloc and blue bloc first became mainstream around the 2011 Danish general election.[9] Left-wing parties are described as belonging to the red bloc while right-wing parties belong to the blue bloc. The Social Democrats and Venstre have historically served as the de facto leaders of the red and blue bloc respectively, though in 2022 leader of the blue bloc party Conservative People's Party Søren Pape Poulsen declared his prime minister candidacy alongside leader of Venstre Jakob Ellemann-Jensen.[10]

The Moderates, founded in 2021 by former prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen, rebuke bloc politics and support a government with parties from both traditional blocs, and use the color purple to represent this.[11] Similarly, The Alternative have refused their designation as a red party declaring they are a green party.[12]

Executive

The government performs the executive functions of the kingdom. The affairs of government are decided by the Cabinet, headed by the Prime Minister. The Cabinet and the Prime Minister are responsible for their actions to the Folketing (the parliament).

Members of the Cabinet are given the title of "minister" and each hold a different portfolio of government duties. The day to day role of the cabinet members is to serve as head of one or more segments of the national bureaucracy, as head of the civil servants to which all employees in that department report.

Head of government

Enjoying the status of primus inter pares, the Prime Minister is head of the Danish government (as taken to mean the Cabinet). The Prime Minister and members of the Cabinet are appointed by the Crown on basis of the party composition in the Folketing. No vote of confidence is necessary to install a new government after an election. If the Folketing expresses its lack of confidence in the Prime Minister, the entire cabinet must step down, unless a new parliamentary election is called in which case the old government continues as a caretaker government until a new government can be formed.

Since the 1990s, most governments have been coalition governments led by either Venstre or the Social Democrats. Until 2001, Poul Nyrup Rasmussen (S) led a coalition with the Social Liberals, supported by the SPP and the Red-Green Alliance. A coalition of Venstre and the Conservatives, supported by the DPP, was then in power from 2001 to 2011, led first by Anders Fogh Rasmussen (V) and then from 2009 by Lars Løkke Rasmussen (V). The Liberal Alliance formed in 2007. After the 2011 election, Løkke was replaced by Helle Thorning-Schmidt (S), whose government consisted of the Social Democrats, the Social Liberals, and the SPP. The SPP left the government again in 2014, following heavy internal disagreement over the planned sale of state-owned shares in the company DONG (now known as Ørsted). The Social Democrats and Social Liberals continued in power, with SPP and Red-Green support, until the 2015 election when Løkke returned to power in a single-party Venstre government. The Løkke II Cabinet held only 34 seats in the Folketing, making it the narrowest since Poul Hartling's (V) 22-seat government in the 1970s, and the first single-party government since Anker Jørgensen's (S) fifth government in the early 1980s. After finding it difficult to govern with such a small government, Løkke invited the Conservatives and the Liberal Alliance to join his government in 2016, turning it into the Løkke III Cabinet.[13]

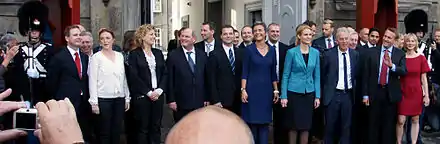

Following the 2019 general election the Social Democrats, led by leader Mette Frederiksen, formed a single-party government with support from the left-wing coalition.[14] Frederiksen became prime minister on 27 June 2019.[15]

In November 2022 general election, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen's Social Democrats remained as the biggest party with two more seats, gaining its best result in two decades.[16] The second biggest was Liberal Party (Venstre), led by Jakob Ellemann-Jensen. The recently formed Moderates party, led by two-time former Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen, became the third-biggest party in Denmark.[17] In December 2022, Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen formed a new coalition government with her Social Democrats and the Liberal Party and the Moderates party. Jakob Ellemann-Jensen became deputy prime minister and defence minister, Lars Lokke Rasmussen was appointed foreign minister.[18]

Cabinet government

According to section 14 of the constitution, the king sets the number of ministers and the distribution of cases between them. The monarch formally appoints and dismisses ministers, including the Prime Minister.[19] That means that the number of cabinet positions and the organisation of the state administration into ministries are not set by law, but subject to change without notice. A coalition of many parties usually means a large cabinet and many ministries, while a small coalition or the rare one-party-government means fewer, larger ministries.

In June 2015 in the wake of the parliamentary election, the cabinet had 17 members including the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister leads the work of the Cabinet and is minister for constitutional affairs, overseas territories and for the affairs of the press. The seventeen cabinet ministers hold different portfolios of duties, including the day-to-day role as head of one or more segments of the government departments.

Government departments

The Danish executive consists of a number of government departments known as Ministries. These departments are led by a cabinet member and known as Minister for the relevant department or portfolio. In theory all Ministers are equal and may not command or be commanded by a fellow minister. Constitutional practice does however dictate, that the Prime Minister is primus inter pares, first among equals. Unlike many other countries, Denmark has no tradition of employing junior Ministers.

A department acts as the secretariat to the Minister. Its functions comprises overall planning, development and strategic guidance on the entire area of responsibility of the Minister. The Minister's decisions are carried out by the permanent and politically neutral civil service within the department. Unlike some democracies, senior civil servants remain in post upon a change of Government. The head of the department civil servants is the Permanent Secretary. In fact, the majority of civil servants work in executive agencies that are separate operational organizations reporting to the Minister. The Minister also has his own private secretary and communications personnel. Unlike normal civil servants, the communications staff is partisan and do not remain in their posts upon changes of government.

List of ministers

Tradition of minority governments

As known in other parliamentary systems of government, the executive (the Cabinet) is accountable to the parliament (the Folketing). Under the Danish constitution, no government may remain in office with a majority against it. This is called negative parliamentarianism, as opposed to the principle of positive parliamentarianism—as in Germany and some other parliamentary systems—a government needs to achieve a majority through a vote of investiture in parliament. It is due to the principle of negative parliamentarianism and its proportional representation system that Denmark has a long tradition of minority governments. Nevertheless, minority governments in Denmark sometimes have strong parliamentary majorities with the help of one or more supporting parties.[2]

The current government of the Social Democrats is stable due to their support by the Social Liberal Party, Socialist People's Party, and the Red–Green Alliance and informally supported by The Alternative. The previous government coalition between Venstre (the Left), the Liberal Alliance, and the Conservatives had support from the Danish People's Party despite not being an official member of the government.[24] This system enables minority parties to govern on specific issues through an ad hoc basis, selecting partners for support based on common interests instead of legislative need. As a result, Danish laws are born of extensive negotiations and compromise. It is common practice for both sides of the Danish political spectrum to cooperate in the Folketing.

Legislature

The Folketing performs the legislative functions of the Kingdom. As a parliament, it is at the centre of the political system in Denmark, and is the supreme legislative body, operating within the confines of the constitution. The Prime Minister is drawn from parliament through the application of the Danish parliamentary principle (a majority must not exist in opposition to the government), and this process is also generally the case for the government also. The government is answerable to parliament through the principle of parliamentary control (question hour, general debates and the passing of resolutions or motions). Ministers can be questioned by members of Parliament regarding specific government policy matters.

General debates on broader issues of government policy may also be held in parliament and may also be followed by a motion of "no-confidence". The opposition rarely requests motions of no-confidence, as the government is usually certain of its majority; however, government policy is often discussed in the plenary assembly of Parliament. Since 1953, the year that marked the reform of the Danish constitution, parliament has been unicameral.

History

With the implementation of the first democratic constitution in 1849, Denmark's legislature was constituted as a bicameral parliament, or Rigsdag, composed of Folketinget (a lower house of commoners) and Landstinget (an upper house containing lords, landowners and industrialists).[25] In 1901, parliamentarism was introduced to the Danish Parliament, which made Folketinget the essential chamber, as no sitting government could have a majority against it in Folketinget. With the constitutional reform of 1953 the Landstinget was abolished, leaving only Folketinget.

1943 dissolution of government

During the occupation of Denmark during the Second World War, on 29 August 1943, the German authorities dissolved the Danish government following the refusal of that government to crack down on unrest to the satisfaction of the German plenipotentiary. The cabinet resigned in 1943 and suspended operations (although the resignation was never accepted by King Christian X).[26]—all day-to-day business had been handed over to the Permanent Secretaries, each effectively running his own ministry. The Germans administered the rest of the country, and the Danish Rigsdag did not convene for the remainder of the occupation[27] until a new one was formed following the liberation on 5 May 1945.

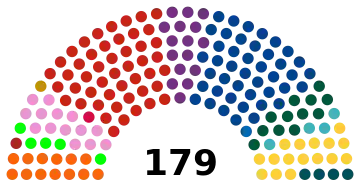

Composition

The Folketing is composed of 179 seats, of which two are reserved for the Faroe Islands and two for Greenland. The remaining 175 seats are taken up by MPs from elected in Denmark. All 179 seats are contested in elections held at least every four years and in the present parliament, all seats are taken up by members belonging to a political party.

All parties receiving more than 2% of the votes are represented in parliament. Comparatively, this is quite low; in Sweden the minimum level of support necessary for getting into parliament is 4%. Often, this has led to the representation of many parties in parliament, and correspondingly complex or unstable government majorities. However, during the last decade the political system has been one of stable majorities and rather long government tenures. Independent politicians running for parliament need about 15,000-20,000 votes in the electoral district they ran in. Since the 1953 constitution of Denmark, only one independent, Jacob Haugaard, has been successful in doing this. Only two politicians have done this in the history of the Danish parliament.

Proportional representation and elections

Denmark uses a system of proportional representation for both national, local, and European Parliament elections. The parliament Folketinget uses a system with constituencies, and a system of allotment is indirectly prescribed in the constitution, ensuring a geographically and politically balanced distribution of the 179 seats. 135 members are proportionally elected in multi-member constituencies, while the remaining 40 seats are allotted nationwide in proportion to the total number of votes a party or list receives. The Faroe Islands and Greenland elect two members each.

Parties must pass a threshold of 2% of the total vote to be guaranteed parliamentary representation. As a consequence of the system, the number of votes required to be elected to parliament varies across the country; it generally requires fewer votes to be elected in the capital, Copenhagen, than it does being elected in less populous areas. Voter turnout in general elections normally lies above 85%, but has been decreasing over time. Turnout is lower in local elections, and lower than that in European Parliament elections.

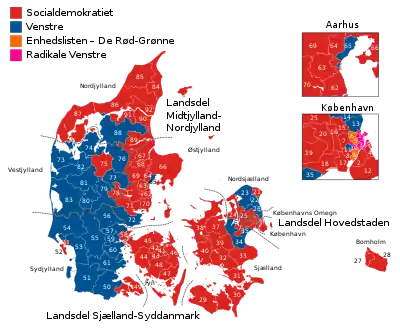

- 2019 election

Overall the election was a win for the "red bloc" – the parties that supported Mette Frederiksen, leader of the Social Democrats, as Prime Minister. In total, the Social Democrats, the Social Liberals, Socialist People's Party and the Red–Green Alliance won 91 seats. Green party The Alternative chose to go into opposition as a "green bloc".[28]

The Social Democrats defended their position as the largest party, and won an additional seat despite a slightly reduced voter share. They were closely followed by Venstre, who saw the largest gains in seats, picking up an extra nine. In the "blue bloc", only Venstre and the Conservative People's Party saw gains, the latter doubling their seats. The Danish People's Party's vote share fell by 12.4 percentage points (pp), well over half of their support. Leader Kristian Thulesen Dahl speculated that the bad result was due to an extraordinary good election in 2015, and that some voters felt they could "gain [their] policy elsewhere".[29] The Liberal Alliance saw their vote share fall by over two-thirds and became the smallest party in the Folketing, only 0.3pp above the 2% election threshold. Their leader Anders Samuelsen was not reelected and he subsequently resigned as leader, succeeded by Alex Vanopslagh.[30][31]

Of the new parties, only New Right won seats, with Hard Line, the Christian Democrats and Klaus Riskær Pedersen failing to cross the national 2% threshold, although the Christian Democrats were within 200 votes of winning a direct seat in the western Jutland constituency.[32] On election night, Klaus Riskær Pedersen announced that he would dissolve his party.[33]

In the Faroe Islands, Republic (which had finished first in the 2015 elections)[34] dropped to fourth place and lost their seat. The Union Party replaced them as the first party while the Social Democratic Party finished in second place again, retaining their seat.[35] In Greenland, the result was a repeat of the 2015 elections, with Inuit Ataqatigiit and Siumut winning the two seats. Siumut regained parliamentary representation after their previous MP, Aleqa Hammond, was expelled from the party in 2016.[36][37] Hammond later joined Nunatta Qitornai,[38] which finished fourth and failed to win a seat.[37][39]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Denmark proper | |||||

| Social Democrats | 914,882 | 25.90 | 48 | +1 | |

| Venstre | 826,161 | 23.39 | 43 | +9 | |

| Danish People's Party | 308,513 | 8.74 | 16 | –21 | |

| Danish Social Liberal Party | 304,714 | 8.63 | 16 | +8 | |

| Socialist People's Party | 272,304 | 7.71 | 14 | +7 | |

| Red–Green Alliance | 245,100 | 6.94 | 13 | –1 | |

| Conservative People's Party | 233,865 | 6.62 | 12 | +6 | |

| The Alternative | 104,278 | 2.95 | 5 | –4 | |

| New Right | 83,201 | 2.36 | 4 | New | |

| Liberal Alliance | 82,270 | 2.33 | 4 | –9 | |

| Stram Kurs | 63,114 | 1.79 | 0 | New | |

| Christian Democrats | 60,944 | 1.73 | 0 | 0 | |

| Klaus Riskær Pedersen | 29,600 | 0.84 | 0 | New | |

| Independents | 2,774 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 3,531,720 | 100.00 | 175 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 3,531,720 | 98.94 | |||

| Invalid votes | 10,019 | 0.28 | |||

| Blank votes | 27,782 | 0.78 | |||

| Total votes | 3,569,521 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 4,219,537 | 84.60 | |||

| Faroe Islands | |||||

| Union Party | 7,360 | 28.32 | 1 | +1 | |

| Social Democratic Party | 6,640 | 25.55 | 1 | 0 | |

| People's Party | 6,181 | 23.79 | 0 | 0 | |

| Republic | 4,832 | 18.60 | 0 | –1 | |

| Progress | 638 | 2.46 | 0 | 0 | |

| Self-Government | 334 | 1.29 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 25,985 | 100.00 | 2 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 25,985 | 99.16 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 220 | 0.84 | |||

| Total votes | 26,205 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 37,264 | 70.32 | |||

| Greenland | |||||

| Inuit Ataqatigiit | 6,867 | 34.35 | 1 | 0 | |

| Siumut | 6,063 | 30.33 | 1 | 0 | |

| Democrats | 2,258 | 11.30 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nunatta Qitornai | 1,622 | 8.11 | 0 | New | |

| Partii Naleraq | 1,564 | 7.82 | 0 | 0 | |

| Atassut | 1,098 | 5.49 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cooperation Party | 518 | 2.59 | 0 | New | |

| Total | 19,990 | 100.00 | 2 | 0 | |

| Valid votes | 19,990 | 97.16 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 585 | 2.84 | |||

| Total votes | 20,575 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 41,344 | 49.77 | |||

| Source: Statistics Denmark, Kringvarp Føroya, Qinersineq | |||||

By constituency

| Constituency | A | B | C | D | E | F | I | K | O | P | V | Ø | Å |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen | 17.2 | 16.4 | 5.3 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 11.5 | 2.6 | 0.7 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 15.0 | 16.8 | 6.5 |

| Greater Copenhagen | 25.8 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 17.2 | 7.2 | 3.1 |

| North Zealand | 21.3 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 6.9 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 7.5 | 1.5 | 23.4 | 5.6 | 2.7 |

| Bornholm | 34.0 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 10.4 | 1.9 | 25.3 | 8.1 | 3.3 |

| Zealand | 28.2 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 8.8 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 10.9 | 2.7 | 24.3 | 5.2 | 2.0 |

| Funen | 30.2 | 7.3 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 6.7 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 8.9 | 1.9 | 23.4 | 6.8 | 3.0 |

| South Jutland | 26.1 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 5.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 12.5 | 1.8 | 28.5 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

| East Jutland | 25.8 | 9.9 | 5.7 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 8.2 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 22.6 | 7.1 | 3.4 |

| West Jutland | 24.6 | 5.3 | 9.2 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 5.3 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 29.8 | 3.4 | 1.7 |

| North Jutland | 33.9 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 9.5 | 1.7 | 26.8 | 4.3 | 2.0 |

Seat distribution

The following is the number of constituency seats for each party with each asterix (*) indicating one of the seats won was a levelling seat.[40]

| Constituency | A | B | C | D | F | I | O | V | Ø | Å | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3* | 1* | 1* | 3 | 4* | 1 | 20 | |

| Greater Copenhagen | 4 | 2* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3* | 1 | 1* | 14 | ||

| North Zealand | 3 | 2* | 2* | 1* | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1* | 14 | ||

| Bornholm | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| Zealand | 8* | 2* | 2* | 1* | 3* | 3* | 7* | 2* | 1* | 29 | |

| Funen | 5* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2* | 4* | 1 | 15 | |||

| South Jutland | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 | 1* | 3 | 6 | 1* | 21 | |

| East Jutland | 7* | 3* | 1 | 1* | 2 | 1* | 2* | 6* | 1 | 1* | 25 |

| West Jutland | 4 | 1 | 2* | 1 | 1* | 1 | 5 | 1* | 16 | ||

| North Jutland | 7* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2* | 5 | 1* | 1* | 19 | ||

| Total | 48 | 16 | 12 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 16 | 43 | 13 | 5 | 175 |

- 2022 election

Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne) was the biggest party with 50 Denmark seats, gaining two more seats. Liberal Party (Venstre) was the second with 23 Denmark seats, losing 20 seats. The third was the biggest winner, recently founded Moderates (Moderaterne) with 16 Denmark seats. Green Left (Socialistisk Folkeparti) secured 15 seats. In 2022 founded anti-immigration, far-right Denmark Democrats (Danmarksdemokraterne) and Liberal Alliance secured both 14 seats.[41]

Judicial system

Denmark has an independent and highly professional judiciary.[42] Unlike the vast majority of civil servants, Danish judges are appointed directly by the Monarch.[43] However, since the constitution ensures the independence of the judiciary from Government and Parliament in providing that judges shall only take into account the laws of the country (i.e., acts, statutes and practices),[44] the procedure on appointments is only a formality.

Until 1999 appointment of judges was the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice, which was also charged with the overall administration of the justice system. On accusations of nepotism and in-group bias, the Ministry in 1999 set up two autonomous boards: the Judicial Appointments Council and the Danish Courts Administration, responsible for court appointments and administration, respectively.[45][46]

Ombudsmanden

The Danish Parliamentary Ombudsman, Jørgen Steen Sørensen,[47] is a lawyer who is elected by parliament to act as a watchdog over the government by inspecting institutions under government control, focusing primarily on the protection of citizens' rights.[48] The Ombudsman frequently inspects places where citizens are deprived of their personal freedom, including prisons and psychiatric hospitals.[47] While the Ombudsman has no power to personally act against the government, he or she can ask the courts to take up cases where the government might be violating Danish law.

The Ombudsman can criticize the government after an inspection and bring matters to public attention, and the government can choose to act upon or ignore his/her criticism, with whatever costs it might have towards the voters and the parliament.

Domestic and foreign relations

The unity of the Realm

Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands used to be dependencies of Denmark. The Danish–Icelandic Act of Union (1918) changed the status of Iceland into that of a kingdom in personal union with Denmark. Iceland remained subordinate to Denmark until independence in 1944 amidst World War II. In the nineteenth century Greenland and the Faroe Islands were given the status of counties, and their own legislatures were disbanded, becoming integral parts of a unitary state.[49] They later gained home rule; the Faroe Islands in 1948 and Greenland in 1979.[49]

Today Greenland and the Faroe Islands are effectively self-governing in regards to domestic affairs,[49] with their own legislatures and executives. However, the devolved legislatures are subordinate to the Folketing where the two territories are represented by two seats each. This state of affairs is referred to as the rigsfælleskab. In 2009 Greenland received greater autonomy in the form of "self-rule".

Foreign policy

The foreign policy of Denmark is based on its identity as a sovereign nation in Europe. As such its primary foreign policy focus is on its relations with other nations as a sovereign independent nation. Denmark has long had good relations with other nations. It has been involved in coordinating Western assistance to the Baltic states (Estonia,[50] Latvia, and Lithuania).[51] The country is a strong supporter of international peacekeeping. Danish forces were heavily engaged in the former Yugoslavia in the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR), with IFOR,[52] and now SFOR.[53] Denmark also strongly supported American operations in Afghanistan and has contributed both monetarily and materially to the ISAF.[54] These initiatives are a part of the "active foreign policy" of Denmark. Instead of the traditional adaptative foreign policy of the small country, Denmark is today pursuing an active foreign policy, where human rights, democracy and other crucial values is to be defended actively. In recent years, Greenland and the Faroe Islands have been guaranteed a say in foreign policy issues, such as fishing, whaling and geopolitical concerns.

Following World War II, Denmark ended its two-hundred-year-long policy of neutrality. Denmark has been a member of NATO since its founding in 1949, and membership in NATO remains highly popular.[55] There were several serious confrontations between the U.S. and Denmark on security policy in the so-called "footnote era" (1982–88), when an alternative parliamentary majority forced the government to adopt specific national positions on nuclear and arms control issues. The alternative majority in these issues was because the Social liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) supported the governing majority in economic policy issues, but was against certain NATO policies and voted with the left in these issues. The conservative led Centre-right government accepted this variety of "minority parliamentarism", that is, without making it a question of the government's parliamentary survival.[55] With the end of the Cold War, however, Denmark has been supportive of U.S. policy objectives in the Alliance.

Danes have enjoyed a reputation as "reluctant" Europeans. When they rejected ratification of the Maastricht Treaty on 2 June 1992, they put the EC's plans for the European Union on hold.[56] In December 1992, the rest of the EC agreed to exempt Denmark from certain aspects of the European Union, including a common defense, a common currency, EU citizenship, and certain aspects of legal cooperation. The Amsterdam Treaty was approved in the referendum of 28 May 1998. In the autumn of 2000, Danish citizens rejected membership of the Euro currency group in a referendum. The Lisbon treaty was ratified by the Danish parliament alone.[57] It was not considered a surrendering of national sovereignty, which would have implied the holding of a referendum according to article 20 of the constitution.[58]

See also

Further reading

- Klint, Thorkil; Evert, Anne Sofie; Kjær, Ulrik; Pedersen, Mogens N.; Hjorth, Frederik (2023). "The Danish legislators database". Electoral Studies.

References

- Munk Christiansen, Peter; Elklit, Jørgen; Nedergaard, Peter, eds. (2020). The Oxford Handbook of Danish Politics (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198833598.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-883359-8.

- Government of Denmark (2011). "About Denmark > Government & Politics". Archived from the original on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

- Corruption Perceptions Index 2012 from Transparency International

- solutions, EIU digital. "Democracy Index 2016 - The Economist Intelligence Unit". www.eiu.com. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- The Danish Monarchy (2011). "Her Majesty The Queen Margrethe 2". The Danish Monarchy. Retrieved 2012-01-12.

- The Danish Monarchy (2011). "The Monarchy today". The Danish Monarchy. Archived from the original on 2015-02-15. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- Gunther, Richard; José R. Montero; Juan José Linz (2002-05-16). Political Parties: Old Concepts and New Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924674-8.

- Denmark.; Bent Rying (1970). Denmark: An Official Handbook (14th ed.). Copenhagen: Krak. ISBN 978-87-7225-011-3.

- Hebsgaard, Thomas (2018-01-15). "Fem grunde til at skrue ned for snakken om rød og blå blok". Zetland (in Danish). Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- "'Bloc politics': A guide to understanding parliamentary elections in Denmark". The Local Denmark. 2022-10-05. Archived from the original on 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- "Løkke: Mit parti bygger på mine værdier, og det er ikke til diskussion". Altinget.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- "Alternativet vil have sin egen blok". Information (in Danish). 2017-01-22. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- "Danish PM invites support parties into government". The Local Denmark. 21 November 2016.

- "Denmark's new leader joins Nordic swing to left". BBC News. 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- "Frederiksen prepares to take over as new Danish prime minister". The Local Denmark. 27 June 2019.

- "Denmark: Mette Frederiksen's Social Democrats win the best result in 20 years". The Progressive Post. 8 November 2022.

- "Denmark election: Centre-left bloc comes out on top". BBC News. 2 November 2022.

- "Danish PM picks right-leaning rivals as key ministers in new government". Reuters. 15 December 2022.

- "Section 14". Constitution of Denmark. ICL. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- Bohr, Jakob Kjøgx (2022-12-15). "Her er SVM-regeringens ministre - TV 2". nyheder.tv2.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2022-12-15.

- "Danmark får ny regering: "Det betyder ikke, vi er enige om alt"". Altinget.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- Nielsen, Morten (2023-03-09). "Stephanie Lose bliver ny minister - TV 2". nyheder.tv2.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2023-03-09.

- "Ellemann bliver forsvarsminister og Løkke bliver udenrigsminister". dr.dk (in Danish). DR. 15 December 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- "What Can Denmark's Left Do With Its Largest Mandate in 60 Years?". www.worldpoliticsreview.com. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- Dickinson, Reginald (1890). "Denmark". Summary of the Constitution and Procedure of Foreign Parliaments. Vacher & sons. pp. 34–45.

- Kaarsted, Tage (1976) De danske ministerier 1929–1953 (in Danish). Pensionsforsikringsanstalten, p. 220. ISBN 87-17-05104-5.

- Jørgen Hæstrup (1979), "Departementschefstyret" in Hæstrup, Jørgen; Kirchhoff, Hans; Poulsen, Henning; Petersen, Hjalmar (eds.) Besættelsen 1940–45 (in Danish). Politiken, p. 109. ISBN 87-567-3203-1.

- Kildegaard, Kasper (6 June 2019). "På en varm dag i juni blev Danmark malet rødt: Nu venter benhårde forhandlinger". Berlingske (in Danish). Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Thulesen: Vi har fået en vælgerlussing". Politiken (in Danish). 5 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Ingvorsen, Emil Søndergård; Nielsen, Kevin Ahrens (9 June 2019). "Alex Vanopslagh bliver Liberal Alliances nye politiske leder". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Thomsen, Per Bang; Toft, Emma (5 June 2019). "Katastrofevalg til Liberal Alliance: Samuelsen er ude af Folketinget". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Søe, Carl-Emil (5 June 2019). "Kristendemokraterne under 200 stemmer fra at komme i Folketinget". TV2 (in Danish). Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Josevski, Aleksandar (5 June 2019). "Klaus Riskær Pedersen opløser sit parti". TV2 (in Danish). Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin størstir KVF, 18 June 2015

- Af Andreas Krog | 6. juni 2019 kl. 9:05 | Print (6 June 2019). "Løsrivelsespartier ryger ud af Folketinget". Altinget.dk. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Omstridte Aleqa Hammond smides ud af rødt valgforbund". DR (in Danish). 19 December 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- "Røde partier vinder valget på Grønland". TV 2 (in Danish). 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Grønlandsk løsrivelsesparti er Løkkes sikkerhedsnet". BT. Ritzau. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Kalaallit Nunaanni Qinersinerit – Valg i Greenland". Valg.gl. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Folketingsvalget den 5. juni 2019". Danmarks Statistik. September 2020. p. 84. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- "The 2022 Danish Elections: Social Democrats Secure | IIEA". www.iiea.com.

- Domstolsstyrelsen (2009-03-20). "The Danish judicial system". domstol.dk. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- Danmarks Domstole (2010). A Closer Look at the Courts of Denmark (PDF). Copenhagen: The Danish Court Administration. ISBN 978-87-92551-14-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-19. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- "The administration of justice shall always remain independent of the executive power. Rules to this effect shall be laid down by Statute..." The Constitution of Denmark – Sections/Articles 62 and 64.

- "The Judicial Appointments Council". Danmarks Domstole. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- Domstolsstyrelsen (2009-03-20). "The Danish Court Administration". domstol.dk. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- Folketingets Ombudsmand. "The Danish Parliamentary Ombudsman". Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- Gøtze, Michael (2010). "The Danish ombudsman A national watchdog with selected preferences". Utrecht Law Review. 6 (1): 33–50. doi:10.18352/ulr.113.

- The unity of the Realm – Statsministeriet – stm.dk. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Danish embassy in Tallinn, Estonia. "Danish - Estonian Defence Cooperation". Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- Danish embassy in Riga, Latvia. "Danish - Latvian Defence Cooperation". Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- Clark, A.L. (1996). Bosnia: What Every American Should Know. New York: Berkley Books.

- Phillips, R. Cody. Bosnia-Hertsegovinia: The U.S. Army's Role in Peace Enforcement Operations 1995–2004. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-97-1.

- "Danmarks Radio - Danmark mister flest soldater i Afghanistan". Dr.dk. 15 February 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Government of the United States. "US Department of State: Denmark". Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- "Maastricht-traktaten & Edinburgh-afgørelsen 18. maj 1993" (in Danish). Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- "Denmark and the Treaty of Lisbon". Folketinget. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- "No Danish vote on Lisbon Treaty". BBC. BBC News. 11 December 2007. Retrieved 20 October 2011.