Piano Sonata in A minor, D 784 (Schubert)

Franz Schubert's Piano Sonata in A minor, D 784 (posthumously published as Op. 143), is one of Schubert's major compositions for the piano.[1] Schubert composed the work in February 1823, perhaps as a response to his illness the year before. It was however not published until 1839, eleven years after his death. It was given the opus number 143 and a dedication to Felix Mendelssohn by its publishers. The D 784 sonata, Schubert's last to be in three movements, is seen by many to herald a new era in Schubert's output for the piano, and to be a profound and sometimes almost obsessively tragic work.

Structure

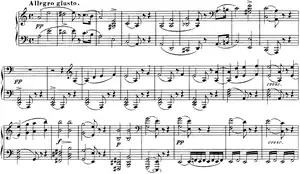

I. Allegro giusto

This movement, in the tonic key of A minor, employs a new, sparse piano texture not found in Schubert's previous works: indeed, over one-fifth of the movement is in bare octaves.[2] Additionally, Schubert also offers a new method of temporal organization to the movement (its tempo and rhythm), and he very unusually does not use much modulation.[2]

The first subject's half-note rhythm, with some dotted notes, is related to the first subject of the D 625 sonata.[2] The "sigh motive" first encountered in bars 2 and 4, ![]()

![]() (with an accented first note), plays a very important role throughout the movement, both in its accentuation (on the downbeat) and its rhythm (abruptly breaking off on a short note).[3] The proliferation of this motive means that rhythm is of key importance for a pianist to maintain coherence throughout the movement.[2] Melodically, the first subject is based around the resolution of the dissonance D♯–E (♯

(with an accented first note), plays a very important role throughout the movement, both in its accentuation (on the downbeat) and its rhythm (abruptly breaking off on a short note).[3] The proliferation of this motive means that rhythm is of key importance for a pianist to maintain coherence throughout the movement.[2] Melodically, the first subject is based around the resolution of the dissonance D♯–E (♯![]() –

–![]() ) and the falling third C–A.[3] Bar 9 transfers this rhythm to the bass, and uses repeated plagal cadences (iv-i) to evoke the atmosphere of a funeral march.[3] At b.26 the first subject returns, now in fortissimo and being followed by parallel chords in dotted rhythms suggesting the French overture – but still ending abruptly on an eighth note on a weak beat.[3]

) and the falling third C–A.[3] Bar 9 transfers this rhythm to the bass, and uses repeated plagal cadences (iv-i) to evoke the atmosphere of a funeral march.[3] At b.26 the first subject returns, now in fortissimo and being followed by parallel chords in dotted rhythms suggesting the French overture – but still ending abruptly on an eighth note on a weak beat.[3]

The transition (b.47) to the second subject is accomplished by accelerating the descending-third motive, now B♭–G, and then reinterpreting the B♭ as A♯ and resolving it to B to prepare the arrival of E major, the dominant major, the key where the second subject will be cast (unusual for a minor-key movement).[3][2] A victorious passage then follows, firmly establishing E major, and seen by Eva Badura-Skoda to express the rhythm and sentiment of the words "Non confundar in aeternam" ("I shall not perish in eternity") from the Te Deum.[4] The calm, hymn-like second subject then follows, is thematically related to the first subject in rhythm and melody. It contains the same downbeat accentuation, although the abrupt breaking off on a short note is not encountered until the subject begins to break into distinct registers at b.75 (it is nevertheless suggested throughout by the portato indication), allowing sudden fortissimo intrusions in the minor and firmly reestablishing the sigh rhythm.[3] The second subject area is shorter than normal for Schubert movements, which Brian Newbould speculates as being due to its creating "such an illusion of space in [its] scarcely-varied somnambulistic tread".[2]

The development section (b.104ff) is based on various incarnations of the first subject, the second subject, and the dotted rhythm that first appeared at b.27. The key oscillates between the submediant (F major, the key of the Andante), and the subdominant (D minor, which has previously appeared at b.34ff).[3] The recapitulation (b.166ff) is a varied repeat of the exposition, but forgoes the dramatic transition passage that appears at b.47ff at the exposition in favour of a pianissimo resolution of E♭ (D♯) and C as part of a fully harmonized augmented sixth to the tonic of A major: Robert S. Hatten notes that, in comparison to the "heroic" and "willful" transition in the exposition, the recapitulation's transition (b.213ff) is "miraculous", and it ties into the even calmer mood of the second subject this time.[3] The calmness of the second subject is further ensured by the triplets that only now appear to lessen the impact of the downbeat accent,[2][3] and the fortissimo intrusions are now followed by diminuendos that suggest that the tragic weight of the sonata is being resolved in this passage.[3]

A coda concludes the movement at b.260ff, based on the "heroic" transition in the exposition, therefore restoring what was initially excluded from the recapitulation.[3] The long-short rhythm then reappears on a tonic pedal in contrasting high and low registers from b.278ff, suggesting once again the calmness of the second theme; but the rude interruption by the descending third in fortissimo at b.286–9 (albeit now C♯–A) suggest that this calmness may prove to be only temporary.[3]

II. Andante (in F major)

Pianist Stephen Hough wrote about this movement: "The second movement is strangely unsettling for three reasons: because of the almost enforced normality of its theme after the bittersweet bleakness of the first movement; because this theme is doubled in the tenor voice, a claustrophobic companion seeming to drag it down; and because of the constant, murmuring interjections (ppp) between the theme’s statements. "

Leo Black has commented that Schubert made use of the same rhythm of the 1818 song "An den Mond, in einer Herbstnacht" in this sonata's slow movement.[1] In addition, Black has noted that Schubert made a musical allusion in the slow movement of the Arpeggione Sonata to the D. 784 sonata.[5]

III. Allegro vivace

In contrast to the slower preceding movements, the final movement contains some of Schubert's most ferocious writing for the piano.

Available recordings

- Radu Lupu, 1970 (Decca)

- Alfred Brendel, 1987 (Philips)

- Maria João Pires, 1989 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- Andras Schiff, 1992 (Decca)

- Evgeny Kissin, 1995 (Sony Classical)

- Stephen Hough, 1999 (Hyperion)

- Mitsuko Uchida, 1999 (Philips)

- Imogen Cooper, 2009 (Avie)

- Paul Lewis, 2012 (Harmonia Mundi)

- Daniel Barenboim, 2014 (Deutsche Grammophon)

- Lucas Debargue, 2017 (Sony Classical)

- Eric Lu, 2022 (Warner Classics)

Notes

- Black, Leo (June 1997). "Oaks and Osmosis". The Musical Times. Musical Times Publications Ltd. 138 (1852): 4–15. doi:10.2307/1003664. JSTOR 1003664.

- Newbould, Brian (1999). Schubert: The Music and the Man. University of California Press. pp. 319–21. ISBN 9780520219571.

- "CSI: Hat5".

- Nineteenth-Century Piano Music, R. Larry Todd, pp.121–3.

- Black, Leo (November 1997). "Schubert's Ugly Duckling". The Musical Times. Musical Times Publications Ltd. 138 (1857): 4–11. doi:10.2307/1004222. JSTOR 1004222.

References

- Tirimo, Martino. Schubert: The Complete Piano Sonatas. Vienna: Wiener Urtext Edition, 1997.

External links

- Piano Sonata D. 784: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Piano Sonata D. 784 played by pianist Maria Perrotta on Classical Connect

- Free downloadable recording by Aviram Reichert (archived on the Wayback Machine)