Czechoslovak Legion

The Czechoslovak Legion (Czech: Československé legie; Slovak: Československé légie) were volunteer armed forces comprised predominantly of Czechs and Slovaks[1] fighting on the side of the Entente powers during World War I and the White Army during the Russian Civil War until November 1919. Their goal was to win the support of the Allied Powers for the independence of Lands of the Bohemian Crown from the Austrian Empire and of Slovak territories from the Kingdom of Hungary, which were then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. With the help of émigré intellectuals and politicians such as the Czech Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and the Slovak Milan Rastislav Štefánik, they grew into a force of over 100,000 strong.

| Czechoslovak Legion | |

|---|---|

Czechoslovak Legion coat of arms | |

| Founded | 1914 |

| Disbanded | 1920 |

| Allegiance | |

| Type |

|

| Size |

|

| Motto(s) | "Nazdar (Hello)" |

| Colors | |

| Equipment | Armored Zaamurets |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | |

| Insignia | |

| Universal Battle flag |  |

| Leader | |

| Merged into | Czechoslovak Army |

| Motives | Czechoslovak independence |

| Part of | World War I

|

| Allies |

|

| Opponents |

|

.jpg.webp)

In Russia, they took part in several victorious battles of the war, including the Zborov and Bakhmach against the Central Powers, and were heavily involved in the Russian Civil War fighting Bolsheviks, at times controlling the entire Trans-Siberian railway and several major cities in Siberia.

After three years of existence as a small unit in the Imperial Russian Army, the Legion in Russia was established in 1917, with other troops fighting in France since the beginning of the war as the "Nazdar" company, and similar units later emerging in Italy and Serbia. Originally an all-volunteer force, these formations were later strengthened by Czech and Slovak prisoners of war or deserters from the Austro-Hungarian Army. The majority of the legionaries were Czechs, with Slovaks making up 7% of the force in Russia, 3% in Italy and 16% in France.[2]

The name Czechoslovak Legion preceded and anticipated the creation of Czechoslovakia.

Involvement in World War I

In Russia

In the first months of World War I, the response of the Czech soldiers and civilians to the war and mobilization efforts were highly enthusiastic; however, it turned into apathy later.[3] As World War I broke out, national societies representing ethnic Czechs and Slovaks residing in the Russian Empire petitioned the Russian government to support the independence of their homelands. To prove their loyalty to the Entente cause, these groups advocated the establishment of a unit of Czech and Slovak volunteers to fight alongside the Russian Army.[4]

On 5 August 1914, the Russian Stavka authorized the formation of a battalion recruited from Czechs and Slovaks in Russia. This unit, called the "Companions" (Družina), went to the front in October 1914, where it was attached to the Russian Third Army.[5] There the Družina soldiers served in scattered patrols performing a number of specialized duties, including reconnaissance, prisoner interrogation and subversion of enemy troops in the opposite trenches.[6]

From its start, Czech and Slovak political émigrés in Russia and Western Europe desired to expand the Družina from a battalion into a formidable military formation. To achieve this goal, however, they recognized that they would need to recruit from Czech and Slovak prisoners of war (POWs) in Russian camps. In late 1914, Russian military authorities permitted the Družina to enlist Czech and Slovak POWs from the Austro-Hungarian Army, but this order was rescinded after only a few weeks due to opposition from other branches of the Russian government. Despite continuous efforts of émigré leaders to persuade the Russian authorities to change their mind, the Czechs and Slovaks were officially barred from recruiting POWs until the summer of 1917. Still, some Czechs and Slovaks were able to sidestep this ban by enlisting POWs through local agreements with Russian military authorities.[7]

Under these conditions, the Czechoslovak unit in Russia grew very slowly from 1914 to 1917. In early 1916, the Družina was reorganized as the 1st Czecho-Slovak Rifle Regiment. During that year, two more infantry regiments were added, creating the Czechoslovak Rifle Brigade (Československá střelecká brigáda). This unit distinguished itself during the Kerensky Offensive in July 1917, when the Czecho-Slovak troops overran Austrian trenches during the Battle of Zborov.[8]

Following the soldiers' stellar performance at Zborov, the Russian Provisional Government finally granted their émigré leaders on the Czechoslovak National Council permission to mobilize Czech, Moravian and Slovak volunteers from the POW camps. Later that summer, a fourth regiment was added to the brigade, which was renamed the First Division of the Czechoslovak Corps in Russia (Československý sbor na Rusi), also known as the Czechoslovak Legion (Československá legie) in Russia. A second division, consisting of four regiments, was added to the Legion in October 1917, raising its strength to about 40,000 troops by 1918.[9]

In France

In France, the Czechs and the Slovaks who wanted to fight Austria-Hungary were allowed to join the Foreign Legion (hence originated the term Legion for units of Czechoslovak volunteers). On 31 August 1914, the 1st Company of the 2nd Infantry Regiment of the Foreign Legion in Bayonne was created mostly of the Czechs and was nicknamed "rota Nazdar" ("Nazdar!" Company). The company distinguished itself in heavy combat during assaults near Arras on May 9 and June 16, 1915. Because of heavy casualties, the company was disbanded, and volunteers continued to fight in various French units.

New autonomous Czechoslovak units were established by the decree of the French government on 19 December 1917. In January 1918, the 21st Czechoslovak Rifle Regiment was formed in the town of Cognac; it mixed prisoners of war with volunteers living in America. The 22nd Czechoslovak Rifle Regiment was created later in May.

In Italy

The creation of Czechoslovak units in Italy took place much later than in France or Russia. In January 1918, the commander of 6th Italian Army decided to form small reconnaissance groups from Czech, Moravian Slovak and Southern Slav volunteers from prisoner-of-war camps. They also served in propaganda actions against the Austrian army. In September 1918 the first fighting unit, the 39th Regiment of the Czechoslovak Italian Legion, was formed from those volunteer reconnaissance squadrons.

Czechoslovak legionaries in Italy were the first to return to newly created Czechoslovakia in 1918 and were immediately drafted into fights for new state borders, most notably in the war against the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Table of units involved in World War I

|

|

|

Flags Used by the Legion

Czechoslovak Legion in Russia Flag (front) [10]

Czechoslovak Legion in Russia Flag (front) [10].svg.png.webp) Czechoslovak Legion in Russia Flag (rear) [10]

Czechoslovak Legion in Russia Flag (rear) [10] Czechoslovak Legion in France Flag 21st Regiment [11]

Czechoslovak Legion in France Flag 21st Regiment [11] Czechoslovak Legion in Italy Flag [12]

Czechoslovak Legion in Italy Flag [12].svg.png.webp) Battalion of the 1st Assault Battalion of the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia[13]

Battalion of the 1st Assault Battalion of the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia[13]

After the breakout of the First World War in 1914, Czech legions were formed with almost one hundred soldiers. Flags of legions’ regiments were white and red with embroidered symbols of the Czech countries and Slovakia, linden twigs, St. Wenceslas’ crown, letters “ S”, and Hussite themes.[14]

The reverse side of the Russian legion's flag showed national colors for the Russian command, and Czech and Slovak colors for the Czechs and Slovaks. The National Council of Czechoslovakia in exile (which led the anti-Austrian resistance) became the interim government on 26 September 1918 with the consent of France, Great Britain, and the US. The first ceremonial hoisting of the Czechoslovak flag on the house inhabited by T. G. Masaryk, the head of the interim government, took place on 18 October 1918. Based on the historical flag of Bohemia, the Czechoslovak flag was defined as the connection of two stripes, i.e. a white one above a red one.[14]

Russian Civil War

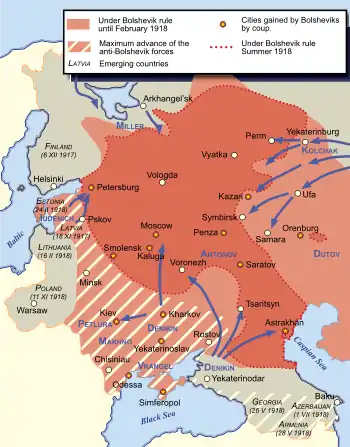

Evacuation from Bolshevik Russia

In November 1917, the Bolsheviks seized power throughout Russia and soon began peace negotiations with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk. The chairman of the Czechoslovak National Council, Tomáš Masaryk, who had arrived in Russia earlier that year, began planning for the Legion's departure from Russia and transfer to France so the Czechoslovaks could continue to fight against the Central Powers. Since most of Russia's main ports were blockaded, Masaryk decided that the Legion should travel from Ukraine to the Pacific port of Vladivostok, where the men would embark on transport vessels that would carry them to Western Europe.[15]

In February 1918, Bolshevik authorities in Ukraine granted Masaryk and his troops permission to begin the 9,700-kilometre (6,000 mi) journey to Vladivostok.[16] However, on 18 February, before the Czechoslovaks had left Ukraine, the German Army launched Operation Faustschlag (fist strike) on the Eastern Front to force the Soviet government to accept its terms for peace. From 5 to 13 March, the Czechoslovak legionaries successfully fought off German attempts to prevent their evacuation in the Battle of Bakhmach.[17]

After leaving Ukraine and entering Soviet Russia, representatives of the Czechoslovak National Council continued to negotiate with Bolshevik authorities in Moscow and Penza to iron out the details of the corps' evacuation. On 25 March, the two sides signed the Penza Agreement, in which the legionaries were to surrender most of their weapons in exchange for unmolested passage to Vladivostok. Tensions continued to mount, however, as each side distrusted the other. The Bolsheviks, despite Masaryk's order for the legionaries to remain neutral in Russia's affairs, suspected that the Czechoslovaks might join their counterrevolutionary enemies in the borderlands. Meanwhile, the legionaries were wary of Czechoslovak Communists who were trying to subvert the corps. They also suspected that the Bolsheviks were being pressured by the Central Powers to stall their movement towards Vladivostok.[18]

By May 1918, the Czechoslovak Legion was strung out along the Trans-Siberian Railway from Penza to Vladivostok. Their evacuation was proving much slower than expected due to dilapidated railway conditions, a shortage of locomotives and the recurring need to negotiate with local soviets along the route. On 14 May, a dispute at the Chelyabinsk station between legionaries heading east and Magyar POWs heading west to be repatriated caused the People's Commissar for War, Leon Trotsky, to order the complete disarmament and arrest of the legionaries. At an army congress that convened in Chelyabinsk a few days later, the Czechoslovaks – against the wishes of the National Council – refused to disarm and began issuing ultimatums for their passage to Vladivostok.[19] This incident sparked the Revolt of the Legions.

Fighting between the Czechoslovak Legion and the Bolsheviks erupted at several points along the Trans-Siberian Railway in the last days of May 1918. By June, the two sides were fighting along the railway route from Penza to Krasnoyarsk. By the end of the month, legionaries under General Mikhail Diterikhs had taken control of Vladivostok, overthrowing the local Bolshevik administration. On July 6, the Legion declared the city to be an Allied protectorate,[20] and legionnaires began returning across the Trans-Siberian Railway to support their comrades fighting to their west. Generally, the Czechoslovaks were the victors in their early engagements against the fledgling Red Army.

By mid-July, the legionaries had seized control of the railway from Samara to Irkutsk, and by the beginning of September they had cleared Bolshevik forces from the entire length of the Trans-Siberian Railway.[21] Legionnaires conquered all the large cities of Siberia, including Yekaterinburg, but Tsar Nicholas II and his family were executed on the direct orders of Yakov Sverdlov less than a week before the arrival of the Legion.

Involvement in the Russian Civil War, 1918–1919

News of the Czechoslovak Legion's campaign in Siberia during the summer of 1918 was welcomed by Allied statesmen in Great Britain and France, who saw the operation as a means to reconstitute an eastern front against Germany.[22] U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, who had resisted earlier Allied proposals to intervene in Russia, gave in to domestic and foreign pressure to support the legionaries' evacuation from Siberia. In early July 1918, he published an aide-mémoire calling for a limited intervention in Siberia by the U.S. and Japan to rescue the Czechoslovak troops, who were then blocked by Bolshevik forces in Transbaikal.[23] But by the time most American and Japanese units landed in Vladivostok, the Czechoslovaks were already there to welcome them.[24]

The Czechoslovak Legion's campaign in Siberia impressed Allied statesmen and attracted them to the idea of an independent Czechoslovak state. As the legionaries cruised from one victory to another that summer, the Czechoslovak National Council began receiving official statements of recognition from various Allied governments.[25]

Capture of Imperial gold reserve

Shortly after they entered into hostilities against the Bolsheviks, the legionaries began making common cause with anti-Bolshevik Russians who began forming their own governments behind the Czechoslovaks' lines. The most important of these governments were the Komuch, led by the Social Revolutionaries, in Samara and the Provisional Siberian Government in Omsk. With substantial Czechoslovak help, the People's Army of Komuch won several important victories, including the capture of Kazan and an Imperial state gold reserve on 5 August 1918. Czechoslovak pressure was also crucial in convincing the anti-Bolshevik forces in Siberia to nominally unify behind the All-Russian Provisional Government, formed at a conference in Ufa during September 1918.[26]

.svg.png.webp)

During the autumn of 1918, the legionaries' enthusiasm for the fighting in Russia, then mostly confined along the Volga and Urals, dropped precipitously. The professor T. G. Masaryk supported them from the United States of America.[27] The rapidly growing Red Army was getting stronger by the day, retaking Kazan on 10 September, followed by Samara a month later.[28] The legionaries, whose strength had peaked at around 61,000 earlier that year,[29] were lacking reliable reinforcements from POW camps and were disappointed by the failure of Allied soldiers from other countries to join them on the front lines. On 28 October, Czechoslovak statehood was declared in Prague, arousing the troops with a desire to return to their homeland. The final blow to Czechoslovak morale arrived on 18 November 1918, when a coup in Omsk overthrew the All-Russian Provisional Government and installed a dictatorship under Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak in control of White Siberia.[30]

During the winter of 1918–1919, the Czechoslovak troops were redeployed from the front to guard the route of the Trans-Siberian Railway between Novonikolaevsk and Irkutsk from partisan attacks. Alongside other legions formed from Polish, Romanian and Yugoslav POWs in Siberia, the Czechoslovaks defended the Kolchak government's only supply route for the duration of 1919.[31]

Betrayal of the White Russians

During the summer and autumn of 1919, Kolchak's armies were in a steady retreat from the Red Eastern Army Group. On 14 November, the Reds took Omsk, Kolchak's capital, initiating a desperate eastward flight by the White army and refugees along the Trans-Siberian Railway. In the following weeks, the Whites' rear was further disorganized by widespread outbreaks of uprisings and partisan activity. The homesick legionaries, who simply wanted to leave Siberia without incurring any more casualties than necessary, declared their neutrality amid the unrest and did nothing to suppress the rebellions. Meanwhile, Kolchak's trains, which included the gold bullion captured from Kazan, were stranded along the railway near Nizhneudinsk. After his bodyguard deserted him there, the legionaries were ordered by Allied representatives in Siberia to convey him to the British military mission in Irkutsk. This plan was resisted by insurgents along the Czechoslovaks' route, and as a result the legionaries, after consulting their commanders, Generals Janin and Jan Syrový, made the controversial decision to turn Kolchak over to the Political Center, a government formed by Socialists-Revolutionaries in Irkutsk. On 7 February 1920, the legionaries had signed an armistice with the Fifth Red Army at Kutin, whereby the latter allowed the Czechoslovaks unmolested passage to Vladivostok. In exchange, the legionaries agreed to not try to rescue Kolchak and to leave the remaining gold bullion with the authorities in Irkutsk. Earlier that day, Kolchak had been executed by a Cheka firing squad to prevent his rescue by a small White army then on the outskirts of the city.[32] His body was dumped under the ice of the frozen Angara River and never recovered.[33]

When the White Army learned about the execution, its remaining leadership decided to withdraw farther east. The Great Siberian Ice March followed. The Red Army did not enter Irkutsk until 7 March, and only then was the news of Kolchak's death officially released. Because of this, and also because of an attempted rebellion against the Whites, organized by Radola Gajda in Vladivostok on 17 November 1919, the Whites accused the Czechoslovaks of treason, but were too weak to act against them.

Evacuation from Vladivostok, 1920

When the armistice with the Bolsheviks was concluded, dozens of Czechoslovak trains were still west of Irkutsk. On 1 March 1920, the last Czechoslovak train passed through that city. The legionaries' progress was still hampered at times by the Japanese Expeditionary Force and the troops of Ataman Grigori Semenov, who stalled the Czechoslovak trains to delay the arrival of the Red Army in Eastern Siberia. By then, however, the evacuation of Czechoslovak troops from Vladivostok was well underway, and the last legionaries left the port in September 1920. The total number of people evacuated with the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia was 67,739; including 56,455 soldiers, 3,004 officers, 6,714 civilians, 1,716 wives, 717 children, 1,935 foreigners and 198 others.[34] After their return to Czechoslovakia, many formed the core of the new Czechoslovak Army.

The number of legionaries killed in Russia during World War I and the Russian Civil War amounted to 4,112.[34] An unknown number went missing or deserted the legion, either to make an arduous journey to return home or to join the Czechoslovak Communists.[35] Among the latter was Jaroslav Hašek, later the author of the satirical novel The Good Soldier Švejk.

Evacuation

A total of 36 transports were dispatched from Vladivostok.

| Country | Quantity | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 36,026 | 53 % |

| Great Britain | 16,956 | 25 % |

| Czechoslovakia*, other allies | 14,921 | 22 % |

| *A part of Centro-Commission | 9,683 | 14.3 % |

- The Allies provided 21 ships—United States 12, Britain 9. Two ships were provided by the American Red Cross. The ships President Grant and Heffron made all or part of the journey twice.

- 12 ships were chartered by the Centrocommission; 9683 people were taken away. Two Japanese ships and one Russian were chartered for cargo. For the transport of people, boats were bought or rented mainly in Japan (7), China (1) and Russia (1). The first ship dispatched by the Centro-Commission was the Japanese Liverpool-Maru, sailing on July 8, 1919. The regular transport of legionnaires and partially disabled people began on December 9, 1919, with the transport of the 1st Regiment on the Jonan-Maru. The last ship with people was the Nizhny Novgorod, which sailed on February 13, 1920. The last ship with cargo was the Shunko-Maru, which sailed from Vladivostok on May 14, 1920.

- The first ship to take the first Siberian legionnaires from Vladivostok was the Italian Roma on January 15, 1919, and the last was the Heffron on September 2, 1920. The first ships sailed to Naples and Marseille. Others passed through the Panama Canal, others to North America, others to Canada with the final port of Hamburg. The whole evacuation took 1 year and 8 months.

- Transport Ships

Japanese ship Shunko-Maru

Japanese ship Shunko-Maru Japanese ship Yonan-Maru

Japanese ship Yonan-Maru Chinese ship Hwah-Yih

Chinese ship Hwah-Yih American ship Madawaska

American ship Madawaska American ship Sheridan

American ship Sheridan American ship America

American ship America American ship President Grant

American ship President Grant American ship Mount Vernon

American ship Mount Vernon Russian ship Nizhny Novgorod

Russian ship Nizhny Novgorod Czechoslovak ship Legion

Czechoslovak ship Legion Ship Titan

Ship Titan Ship Archer

Ship Archer

| Ship Name | Country of Origin | Quantity | Departed from Vladivostok | Arrival Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roma | Kingdom of Italy | 139 | 15. 1. 1919 | 10. 3. 1919 Naples |

| Liverpool Maru | Czechoslovakia | 139 | 9. 7. 1919 | 12. 9. 1919 Marseille |

| Nižnij Novgorod | Russia | 664 | 13. 2. 1920 | 8. 4. 1920 Trieste |

| Mount Vernon | Germany, USA | 3,452 | 13. 4. 1920 | 6. 6. 1920 Trieste |

| Amerika | Germany, USA | 6,478 | 23. 4. 1920 | 7. 6. 1920 Trieste |

| President Grant | Germany, USA | 5,471 | 27. 4. 1920 and 24. 8. 1920 | 12. 6. 1920 and 13. 10. 1920 Trieste |

| Ixion | Germany, United Kingdom | 2,945 | 23. 5. 1920 | 17. 7. 1920 Cuxhaven |

| Dollar | Germany, United Kingdom | 3,427 | 6. 6. 1920 | 20. 7. 1920 Cuxhaven |

| Legie | Japan, Czechoslovakia | 70 or 87 | 24. 8. 1920 | 12. 10. 1920 Trieste |

| Heffron | USA | 720 then 875 | 13. 8. 1919 and 2. 9. 1920 | 17. 12. 1919 and 11. 11. 1920 Trieste |

Ranks of the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia

Officers

| Rank group | Generals | Field Officers | Company Officers | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) |

.png.webp) | |||||||||||||

| Generál zbrani | Generálporučík | Generálmajor | Plukovník | Podplukovník | Kapitan Major Oct. 1918 |

Podkapitán Kapitán Oct. 1918 |

Poručík | Podoručík | Praporčík | |||||||||||||

Postwar

Czechoslovakia declared its independence from the disintegrating Austria-Hungary, on 28 October 1918 with now President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk of the Czechoslovak Republic. Members of the Legions formed a significant part of the new Czechoslovak Army. A French military mission began in Czech territories after January 1919, led by General Maurice Pellé. After some disagreements with the Italian-led Czechs in Slovakia,[37] President Masaryk eventually replaced Piccione with Pellé on July 4, 1919, and essentially ended the Italian connection to the Legion.[38]

The French military mission's role was to integrate the existing Czechoslovak Foreign Legions with the home units of the Army and develop a professional command structure. On October 15, 1919, the main staff of the Czechoslovak Army was officially formed. French officers were installed as territorial commanders and commanders of some divisions. Over the course of time, there were 200 French non-commissioned officers, over 100 commissioned officers and 19 Generals. General Pellé and his immediate replacement, General Eugène Mittelhauser (also French), were the first chiefs staff of the Czechoslovak Army.

The Legion took part in the Hungarian–Czechoslovak War. On January 1, 1919, Legion troops took control of the city of Bratislava and Italian Colonel Riccardo Barreca was appointed military commander of the city. Several clashes (which killed at least nine Hungarian demonstrators) took place and Barreca himself was injured. The Italian officers continued to assist in the operations against the Hungarians during the war. Many veterans of the legion also fought in the Polish–Czechoslovak War.

Legion veterans formed organizations such as the Association of Czechoslovak Legionnaires (Československá obec legionářská) and Legiobanka (Legionářská banka, a bank formed with the capital they had gathered during their long service). These and other organizations were known as the Hrad ("The [Prague] Castle") for their support of the President of Czechoslovakia.

In literature

The 2005 novel The People's Act of Love, by the British writer James Meek, describes the occupation of a small Siberian town by a company of the Czechoslovak Legion in 1919. The original inhabitants of the town are members of the Christian sect of Skoptsy, or castrates.

A memoir Přál jsem si míti křídla by Jozef Dufka was published in magazine Zvuk during 1996-1999 and as a book in 2002 (ISBN 80-86528-08-1).[39][40]

Gustav Becvar (August Wenzel Engelbert (Gustav) Bečvář[41]) published his memoir The Lost Legion in English in 1939.[40]

In art

Two postage stamps, issued in 1919, were printed for use by Czechoslovak Legion in Siberia.

The flag of the Czechoslovak Legion can be seen in the Allies in the monumental painting Pantheon de la Guerre.

Last Train Home is an upcoming real-time strategy video game developed by Ashborne Games, in which the player controls a train carrying Czechoslovak Legion troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway during their withdrawal.[42][43] It is scheduled for 2023 release.[44][45]

References

- "Nad Tatrou sa blýska - (10)". Valka.cz.

- "Češi bojovali hrdinně za Rakousko-Uhersko, ale první republika to tutlala". zpravy.idnes.cz. 27 October 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- John Richard Schindler (1995). A Hopeless Struggle: The Austro-Hungarian Army and Total War, 1914–1918. McMaster University. p. 50. ISBN 978-0612058668.

- John Bradley, The Czechoslovak Legion in Russia 1914–1920 (Boulder: East European Monographs, 1990) 14–16.

- Josef Kalvoda, The Genesis of Czechoslovakia (Boulder: East European Monographs, 1986) 62–63.

- Bradley, Czechoslovak Legion, 41.

- Brent Mueggenberg, The Czecho-Slovak Struggle for Independence 1914–1920 (Jefferson: McFarland, 2014) 67–70.

- Mueggenberg, Czecho-Slovak Struggle, 86–90.

- Kalvoda, Genesis, 101–105.

- "Vhu Praha".

- "Vhu Praha".

- "Vhu Praha".

- "Vhu Praha".

- "History of the flag of the Czech".

- Victor M. Fic, Revolutionary War and the Russian Question (New Delhi: Abhinav, 1977) 36–39.

- Tomáš Masaryk, The Making of a State, Translated by Henry Wickham Steed (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1927) 177.

- Henry Baerlein, The March of the Seventy Thousand (London: Leonard Parsons, 1926) 101–103, 128–129.

- Victor M. Fic, The Bolsheviks and the Czechoslovak Legion (New Delhi: Abhinav, 1978) 22–38.

- Fic, Bolsheviks, 230–261.

- "Czech troops take Russian port of Vladivostok for Allies – Jul 6, 1918". History.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- Mueggenberg, Czecho-Slovak Struggle, 161–177, 188–191.

- George Kennan, Soviet-American Relations: The Decision to Intervene (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1958) 357–358, 382–384.

- Kennan, Decision to Intervene, 395–408.

- Benjamin Isitt, From Victoria to Vladivostok: Canada's Siberian Expedition, 1917–19 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press)

- Mueggenberg, Czecho-Slovak Struggle, 185–188.

- Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy (New York: Viking, 1997) 580–581.

- PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3, pages 124 - 128,140 - 148,184 - 190

- Mueggenberg, Czecho-Slovak Struggle, 196–197.

- Josef Kalvoda, "Czech and Slovak Prisoners of War in Russia during the War and Revolution", Peter Pastor, ed., Essays on World War I (New York: Brooklyn College Press, 1983) 225.

- Mueggenberg, Czecho-Slovak Struggle, 215–225.

- Mueggenberg, Czecho-Slovak Struggle, 249.

- Jonathon Smele, Civil War in Siberia (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996) 544–665.

- Fleming, Peter (1963). The Fate of Admiral Kolchak. Harcourt, Brace, & World, Inc. pp. 216–217.

- Bradley, Czechoslovak Legion, 156.

- Joan McGuire Mohr, The Czech and Slovak Legion in Siberia 1917–1922 (Jefferson: McFarland, 2012) 157.

- Purdek, Imrich (2013). Československá vojenská symbolika 1914-1939. Bratislava: Vojenský historický ústav, p. 73.

- As an example, General Piccione did not consider the agreed demarcation line to be militarily advantageous. Therefore, he decided to move his troops to the south into Hungary. Although he notified the Hungarian government, he advanced, on January 16, 1919, before any reply. The Hungarians disagreed with the new demarcation action. At the order of the Czech government, Piccione returned his troops to the original demarcation line. See http://www.svornost.com/20-ledna-1919-dokonceno-osvobozovani-slovenska-cs-armadou-a-dobrovolniky

- Wandycz,P., France and her Eastern Allies 1919-1925, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis (1962)

- "Přál jsem si míti křídla - Josef Dufka | Databáze knih". www.databazeknih.cz.

- "'A Czechoslovakian epic': the Czechoslovak Legion in the Russian Revolution - European studies blog". blogs.bl.uk.

- "Galerie osobností města Nového Jičína". galerieosobnosti.muzeumnj.cz.

- Franzese, Tomas (11 June 2023). "Last Train Home turns World War 1 history into a strategy game". Digital Trends. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Brown, Andy (11 June 2023). "'Last Train Home' trailer reveals a gritty strategy set in the aftermath of WW1". NME. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Bigas, Jiří. "Nová hra z Brna vypráví příběh československých legií v Rusku". Vortex. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- Burian, Michal. "Last Train Home s českým dabingem přinese strastiplný návrat československých legionářů". INDIAN (in Czech). Retrieved 12 June 2023.

Further reading

- Baerlein, Henry, The March of the 70,000, Leonard Parsons/Whitefriar Press, London 1926.

- Bullock, David: The Czech Legion 1914–20, Osprey Publishers, Oxford 2008.

- Clarke, William, The Lost Fortune of the Tsars, St. Martins Press, New York 1994 pp. 183–189.

- Fic, Victor M., The Bolsheviks and the Czechoslovak Legion, Shakti Malik, New Delhi 1978.

- Fic, Victor M., Revolutionary War for Independence and the Russian Question, Shakti Malik, New Delhi, 1977.

- Fleming, Peter, The Fate of Admiral Kolchak, Rupert Hart Davis, London 1963.

- Footman, David, Civil War in Russia, Faber & Faber, London 1961.

- Goldhurst, Richard, The Midnight War, McGraw-Hill, New York 1978.

- Hoyt, Edwin P., The Army Without a Country, MacMillan, New York/London 1967.

- Kalvoda, Josef, Czechoslovakia's Role in Soviet Strategy, University Press of America, Washington DC 1981.

- Kalvoda, Josef, The Genesis of Czechoslovakia, East European Monographs, Boulder 1986.

- McNamara, Kevin J., ''Dreams of a Great Small Nation: The Mutinous Army that Threatened a Revolution, Destroyed an Empire, Founded a Republic, and Remade the Map of Europe,'' Public Affairs, New York 2016.

- McNeal, Shay, The Secret Plot to Save the Tsar, HarperCollins, New York 2002 pp. 221–222.

- Meek, James, The People's Act of Love, Canongate, Edinburgh, London, New York 2005.

- Mohr, Joan McGuire, The Czech and Slovak Legion in Siberia from 1917 to 1922. McFarland, NC 2012.

- Mueggenberg, Brent, The Czecho-Slovak Struggle for Independence 1914–1920, McFarland, Jefferson, 2014.

- Preclík, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (TGM and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk democratic movement in Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3.

- Unterberger, Betty Miller, The United States, Revolutionary Russia, and the Rise of Czechoslovakia, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2000.

- White, John Albert, The Siberian Intervention, Princeton University Press, Princeton 1950.

- Cestami odboje, memoirs of Czechoslovak Legion soldiers in Russia, France and Italy published in "Pokrok" (Prague) between 1926 and 1929.

Note: There were quite a few books on the Legion written in Czech that were published in the 1920s, but most were hard to find following Soviet victory in World War II.

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

.png.webp)