Cystoisospora belli

Cystoisospora belli, previously known as Isospora belli, is a parasite that causes an intestinal disease known as cystoisosporiasis.[1] This protozoan parasite is opportunistic in immune suppressed human hosts.[2] It primarily exists in the epithelial cells of the small intestine, and develops in the cell cytoplasm.[2] The distribution of this coccidian parasite is cosmopolitan, but is mainly found in tropical and subtropical areas of the world such as the Caribbean, Central and S. America, India, Africa, and S.E. Asia. In the U.S., it is usually associated with HIV infection and institutional living.[3]

| Cystoisospora belli | |

|---|---|

| |

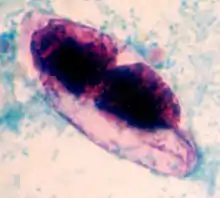

| strained oocyst of Cystoisospora belli | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Conoidasida |

| Order: | Eucoccidiorida |

| Family: | Sarcocystidae |

| Genus: | Cystoisospora |

| Species: | C. belli |

| Binomial name | |

| Cystoisospora belli (Wenyon, 1923) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Isospora belli | |

Morphology

A fully mature (sporulated) oocyst of genus Isospora is a spindle-shaped body that has two sporocysts that contain four sporozoites each.[4] The oocysts of Cystoisospora belli are long and oval shaped. They measure between 20 and 33 micrometers in length and between 10 and 19 micrometers wide.[5]

Life cycle

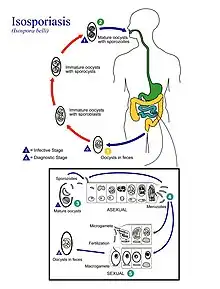

- An oocyst with one sporoblast is released in stool of infected person

- After the oocyst has been released, the sporoblast matures further and divides into two

- After the sporoblasts divide they create a cyst wall and become sporocysts

- The sporocysts each divide twice, resulting in four sporozoites

- Transmission occurs when these mature oocysts are ingested

- The sporocysts excyst in the small intestine where sporozoites are released

- The sporozoites then invade epithelial cells and schizogony is initiated

- When the schizonts rupture, merozoites are released and continue to invade more epithelial cells

- Trophozoites develop into schizonts, containing many merozoites

- After about one week, development of male and female gametocytes begin in the merozoites

- Fertilization results in the development of oocysts, which are released in the stool [1][6]

The sporulation time of this parasite's egg is usually 1–4 days, and the entire life cycle takes about 9–10 days.[7] The infective stage found in stool is the mature oocyst.[1] The mature oocyst for Cystoisospora belli can remain infective in the environment for months.[8]

Symptoms

Immune competent individuals are usually asymptomatic to this parasite's infection. But clinical symptoms such as mild diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and low grade fever for approximately one week has been observed in some individuals.[2]

Immunocompromised people are more severely affected by Cystoisospora belli and can experience extreme diarrhea that can lead to weakness, anorexia, and weight loss. Other symptoms of cystoisosporiasis include abdominal pain, cramps, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and fever, that can last from weeks to months.[1][5][9]

Diagnosis and treatment

Cystoisospora belli is diagnosed by identification of the oocyst through examining a stool sample under a microscope. The diagnostic stage is the immature oocyst that contains a spherical mass of protoplasm. In other words, the oocyst that is diagnosed in the stool sample is unsporulated, and contains only one sporoblast.[2] For stool diagnosis, direct smear, concentration smear, microscopic wet mount, or iodine stains of fecal smears are adequate. But for easy screening, acid-fast stains is recommended.[2][3] If stool test is negative, and biopsies of the small intestine is performed, different stages of schizogony and sporogony should exist in the epithelial cells, but the alteration of the villi is not necessarily present.[2]

Eosinophilia may also be seen unlike in the case of other protozoal infections.[3]

This infection is easily treated with antibiotics. The most common antibiotic that is prescribed is co-trimoxazole (trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole), more commonly known as Bactrim, Septra, or Cotrim.[1]

In AIDS patients, treatments can result in the disappearance of the symptoms, but recurrence of symptoms is common.[2] In order prevent the recurrence, medication is continued in AIDS patients and other immunosuppressed patients.[10]

Transmission and prevention

Cystoisospora belli does not require an intermediate host and currently is only known to transmit from person to person.[11] The method of transmission is ingesting food or water that has been contaminated with feces from someone who is infected.[1] Washing your hands with soap and warm water after using the toilet, changing diapers, and before handling food is vital. Also, educating children the importance of hand-washing and good hygiene practice is important.[1] Because HIV-AIDS patients will have higher risk of symptomatic intestinal parasitic infections, and pathogenic burden can increase disease progression and contributes to early death, routine screening of parasites especially in patients with lower CD4 count should be emphasized.[12]

History

Isospora belli was discovered by Rudolf Virchow in 1860 and was named by Charles Morley Wenyon in 1923. The parasite is now known as Cystoisospora belli.[5]

References

- Centers For Disease Control: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cystoisospora/index.html%5B%5D

- Gutierrez, Yezid (1990). Diagnostic pathology of parasitic infections with clinical correlations. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. pp. 97–103. ISBN 978-0812112375.

- Auwaerter, Paul. "Cystoisospora belli". Johns Hopkins Guides. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- Roberts, Larry S.; Janovy, John Jr. (2009). Gerald D. Schmidt & Larry S. Roberts' Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. pp. 133–134. ISBN 9780073028279.

- Garcia, L. (2006). "Isospora belli". Waterborne Pathogens. Denver: American Water Works Association. pp. 217–9. ISBN 978-1-58321-403-9.

- "Cystoisospora belli" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Lapage, Geoffrey (1968). Veterinary Parasitology (Second ed.). Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas. p. 967.

- Murphy, Sean C.; Hoogestraat, Daniel R.; SenGupta, Dhruba J.; Prentice, Jennifer; Chakrapani, Andrea; Cookson, Brad T. (2017-04-21). "Molecular Diagnosis of Cystoisosporiasis Using Extended-Range PCR Screening". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 13 (3): 359–362. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.01.007. ISSN 1525-1578. PMC 3077734. PMID 21458380.

- Velásquez, Jorge Néstor; Astudillo, Osvaldo Germán; Di Risio, Cecilia; Etchart, Cristina; Chertcoff, Agustín Víctor; Perissé, Gladys Elisabet; Carnevale, Silvana (2010). "Molecular characterization of Cystoisospora belli and unizoite tissue cyst in patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome". Parasitology. 138 (3): 279–86. doi:10.1017/S0031182010001253. hdl:11336/191919. PMID 20825690. S2CID 21888232.

- Pape, J. W.; Verdier, R. I.; Johnson, W. D. (1989-04-20). "Treatment and prophylaxis of Isospora belli infection in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 320 (16): 1044–1047. doi:10.1056/NEJM198904203201604. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 2927483.

- "Cystoisospora belli - Overview - Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- Gupta, K., Bala, M., Deb, M., Muralidhar, S., & Sharma, D. K. (2013). Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in HIV-infected individuals and their relationship with immune status. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, 31(2), 161-165. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.115247