Cynthia Lennon

Cynthia Lennon (née Powell; 10 September 1939 – 1 April 2015) was the first wife of John Lennon and the mother of Julian Lennon.

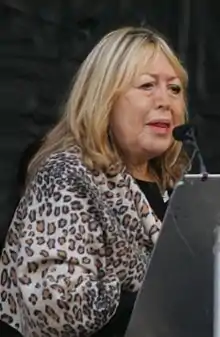

Cynthia Lennon | |

|---|---|

Lennon in October 2010 | |

| Born | Cynthia Powell 10 September 1939 Blackpool, England |

| Died | 1 April 2015 (aged 75) Palma Nova, Mallorca, Spain |

| Spouses | Roberto Bassanini

(m. 1970; div. 1976)John Twist

(m. 1978; div. 1982)Noel Charles

(m. 2002; died 2013) |

| Children | Julian Lennon |

Born in Blackpool and raised in Hoylake on the Wirral Peninsula, she attended the Liverpool College of Art where Lennon was also a student. Powell and Lennon started a relationship after meeting in a calligraphy class. When Lennon was performing in Hamburg with the Beatles, Powell rented his bedroom at 251 Menlove Avenue in the Liverpool suburb of Woolton from his aunt and legal guardian, Mimi Smith. After Powell became pregnant, she and Lennon married in August 1962, and the couple lived at Kenwood in Weybridge from 1964 to 1968, where she kept house and participated with Lennon in a London-based social life. In 1968, Lennon left her for Japanese artist Yoko Ono; as a result, the couple's divorce was legally granted in November 1968 on the grounds of adultery.

Powell had three further marriages. She published a book of memoirs, A Twist of Lennon, in 1978, and a more intimate biography, John, in 2005. Over the years, she held several auctions of memorabilia associated with her life with Lennon. In her later years she lived in Palma Nova, Mallorca, where she died in 2015.

Early years

Cynthia Powell was born in Blackpool on 10 September 1939,[1] the youngest of three children of General Electric Company employee Charles Powell[2] and his wife Lillian (née Roby), who already had two sons named Charles and Anthony.[3] Her parents were from Liverpool, but her mother (along with other pregnant women) was sent to the safer area of Blackpool after World War II had been declared and lived in a small room in a bed-and-breakfast on the Blackpool seafront.[2] After the birth, with Liverpool becoming a frequent target of German air raids, the Powell family moved to a two-bedroomed semi-detached house in Hoylake,[2] a middle-class area on the Wirral Peninsula which was considered "posh" by those in Liverpool.[4] At the age of 11, Powell won an art prize in a competition organised by the Liverpool Echo.[5] A year later, she was accepted into Liverpool's Junior Art School,[6] which was also attended by Bill Harry, later the editor of Liverpool's Mersey Beat newspaper.[7]

Art college

When Powell was 16, her father died following a lengthy bout with lung cancer.[8] Before he died, he told her she would have to get a job to support her mother, and would not be able to go to art school. As her mother wanted her to receive an education, she rented out a room to four apprentice electricians.[2] In September 1957, Powell gained a place at the Liverpool College of Art.[9] Although studying graphics, she also took lettering classes, as did Lennon.[10] He never had any drawing tools with him, so he constantly borrowed pens and pencils from Powell, who discovered he was only there because other teachers had refused to instruct him.[11] She had an air of respectability and moved in different social circles than her future husband. Lennon and an art school friend, Jeff Mohammed, used to make fun of her by stopping the conversation when she walked in the room, saying: "Quiet please! No dirty jokes; it's Cynthia."[4]

Powell once overheard Lennon give a compliment to a girl with blonde hair in the college, who looked similar to the French actress Brigitte Bardot. The next Saturday, Powell turned up at the college with her hair several shades blonder.[10] Lennon noticed straight away, exclaiming, "Get you, Miss Hoylake!" (Lennon's nickname for her,[9] along with "Miss Powell" or "Miss Prim").[12] Dressed like a Teddy Boy, he sometimes brought a guitar with him into class, and once sang "Ain't She Sweet" directly to Powell.[13]

Relationship with John Lennon

After a college party to celebrate the end of term, Lennon asked Powell if she would like to "go out" with him.[14] She quickly replied that she was engaged to a young man in Hoylake even though the engagement had ended;[15][16] he replied, "I didn't ask you to fucking marry me, did I?"[17][18] He later approached her and asked if she would go to the Ye Cracke pub. She was confused when he ignored her all evening, but eventually invited her into the group with a joke.

They began dating, with Lennon now referring to her as "Cyn".[19] In the autumn of 1958, she ended her engagement to be with him,[15] and he ended his relationship with another art student, Thelma Pickles.[20][21] His jealousy could also manifest itself in violent behaviour towards her,[22] as when he slapped her across the face (causing her head to hit a wall),[23] after watching her dance with Stuart Sutcliffe.[24] After the incident, she broke up with Lennon for three months, but resumed their relationship after his profuse apology.[25]

Her work at art school began to suffer, and teachers told her the relationship with Lennon was doing her no good. Lennon continued to be casually inconsiderate towards her, later saying, "I was in sort of a blind rage for two years. I was either drunk or fighting. It had been the same with other girl friends I'd had. There was something the matter with me."[26] Tony Bramwell—a friend of Lennon's since his youth—later said: "Cynthia was beautiful, physically, and on the inside. Although she knew he [Lennon] was apt to find love on the road, she was totally dedicated to his success... and extremely influential. He was insecure and Cynthia was there to pump him up, to buttress, sort of, his weak side."[27]

The Beatles' first Hamburg residency took place in 1960, with Lennon writing frequent and passionate letters back home to Powell.[28] After returning home, Lennon's aunt and legal guardian, Mimi Smith, threw a hand-mirror at him for spending a lot of money on a suede coat for Powell. Smith later referred to her as "a gangster's moll", and was often unpleasant towards her.[29] The Beatles went to Hamburg for a second time in 1961, and both Powell and Dot Rhone (Paul McCartney's girlfriend at the time), visited them two weeks later, during the Easter holidays.[30][31] They had to stay up all night because of the long sets, both taking Preludin to stay awake, which the group was also taking.[32] Lennon and Powell stayed with Sutcliffe's girlfriend, Astrid Kirchherr, at her mother's house.[30]

After the trip to Hamburg, Powell's mother Lillian said Powell's cousin and husband were emigrating to Canada with their new-born baby,[33] and that she, Lillian, would be going with them while they studied to become teachers.[34] Powell waited until Lennon came back from Hamburg before she asked Smith—who had taken in lodgers before at 251 Menlove Avenue—if she would rent a room to her. Smith rented out the box-room above the front door (which had been Lennon's bedroom), but insisted she also do chores around the house. After her student grant had run out, she took a job at a Woolworths store in Liverpool in order to pay the rent.[35] In the same year, when Lennon was 21 years old, he received £100 (equivalent to £2,400 in 2023)[36] from his aunt Elizabeth Sutherland (whom he called "Mater") who lived in Edinburgh, and went to Paris with McCartney. Powell could not accompany them as she was studying for her final exams.[37]

When Lennon went to Hamburg again in April 1962, she found a bedsit in a terraced house at 93 Garmoyle Road, Liverpool.[38] Shortly after having failed her art teacher's diploma exam,[39] in August 1962,[40] she found she was pregnant with Lennon's child.[35] She later explained that she and Lennon had never used contraception, had never talked about it, and did not think about it at the time. When she told Lennon he said, "There's only one thing for it Cyn, we'll have to get married".[41]

Marriage to Lennon and birth of Julian

Powell and Lennon were married on 23 August 1962[42] at the Mount Pleasant register office in Liverpool.[43] Fellow Beatles McCartney and George Harrison were in attendance, as was their manager, Brian Epstein, who was best man; no parents were there.[43][44][45] The wedding was farcical, because as soon as the ceremony began a workman in the backyard of the building opposite started using a pneumatic drill that drowned out anything the registrar, Lennon, or Powell said. When the registrar asked for the groom to step forward, Harrison stepped forward instead.[46] With no photographs or flowers the wedding party celebrated afterwards, at Epstein's invitation, in Reece's restaurant in Clayton Square, which was the place Lennon's parents, Alfred Lennon and Julia Lennon, had celebrated their marriage in 1938.[46] Lennon was 21 years old, and Powell 22.[33] The newlyweds had no honeymoon, as Lennon had to play an engagement at the Riverpark Ballroom in Chester the same night.[46] They travelled to the Hotel George V in Paris[47] for a belated honeymoon on 16 September[48] but were accompanied by Epstein,[49] even though he had not been invited to join them.[50]

During Powell's pregnancy, Epstein offered her and Lennon the use of his flat at 36 Falkner Street, Liverpool, and later paid for a private hospital room when the pregnancy was coming to term.[51] Although still unknown outside Liverpool, by now the Beatles had a fanatical following among girls within the city.[45] Epstein had one condition which the Lennons had to follow: the marriage and the baby were to be kept a close secret, so as not to upset any of these fans.[52][45] One time when news of the wedding leaked out, the group denied it.[45]

The Lennons' son, Julian,[53] was born at 7.45 am on 8 April 1963, in Sefton Hospital.[54] Lennon, being on tour at the time, did not see his son until three days later,[53] and when he finally arrived at the hospital, said: "He's bloody marvellous, Cyn! ... Who's gonna be a famous rocker like his Dad then?"[55] He then explained that he would be going on a four-day holiday to Barcelona, with Epstein.[56] Lennon later referred to Julian as a "Saturday night special; the way that most people get here", or said that his son "came out of a whisky bottle,"[57] suggesting this as explanation for his poor parenting of Julian as compared to his second son, Sean Lennon: "Sean is a planned child, and therein lies the difference. I don't love Julian any less as a child."[58]

Beatlemania

Around the time of Julian's birth, the Beatles became a pop sensation across Britain, a phenomenon which became known as Beatlemania.[59] That one of the members was married and had a son was not publicly known at the time; a 1963 "Lifelines of the Beatles" page in the New Musical Express detailed over 25 biographical facts about each member of the group, but never gave any hint Lennon was married, even reporting "girls" as one of his hobbies.[60]

The press heard rumours about Lennon's wife and child at the end of 1963—after Beatlemania had already swept the UK and Europe—and descended on her mother's house in Hoylake (where mother and son were staying), in November and December.[61] Friends and neighbours protected their anonymity, but she was often approached by journalists.[62] In November, she had her son christened at Hoylake Parish Church, but didn't tell Lennon (who was on tour at the time), because she feared a media circus. She told him two days after, and he was angry as he hadn't wanted his son to be christened,[63] even though Epstein had asked to be Julian's godfather. Not long after the christening, every newspaper was full of the story about Lennon's secret wife and baby boy.[64]

Brian Epstein told the other Beatles to make the best of the situation, and hoped newspapers would not say Cynthia was pregnant before marrying him.[65] After living at Lennon's aunt's house for some months, the couple moved to London and found a three-bedroomed flat at 13 Emperor's Gate, off Cromwell Road.[66] The top floor flat was the third of three, which were each built over two floors. This meant climbing six flights of stairs, as the building had no lift. Cynthia firstly had to carry Julian up to the flat, and then go back down to collect shopping bags.[67] The Beatles' fans soon found out where they were living, and she would find them camping out in the hallway, and have to push through them when leaving or arriving.[68]

She accompanied Lennon to the United States in the first Beatles' tour there, with Lennon allowing the press to photograph them together,[69] which infuriated Epstein, as he had wanted to keep their marriage a secret.[70] On the tour, she was left behind in New York when Lennon and the other Beatles were quickly ushered into a car, and in Miami she had to ask the help of fans to convince a security guard who she was. Lennon's response was, "Don't be so bloody slow next time—they could have killed you".[71] It would be the only time Cynthia would go on tour with them.[72] At the Emperor's Gate address the situation grew worse,[22] with fans sticking chewing gum in the lock of the flat and tearing at any article of clothing when she or Lennon were leaving or arriving.[73] American girls would write her letters proclaiming their desperate love for John; the women in the lives of the other Beatles received equivalent missives.[74] As late as 1967, Beatles' wives were still dealing with occasional physical danger from female Beatles fans, with Cynthia being kicked in the legs by one who demanded she "leave John alone!"[75]

As Lennon was either touring or recording, supposed family holidays in 1966 were spent skiing in St. Moritz, with producer George Martin and his girlfriend, or staying at a castle in Ireland, with George Harrison and his wife Pattie Boyd.[76] Even these were subject to being discovered by fans, and Cynthia and Boyd had to escape the Irish location dressed as maids.[74] As a result of the long recording sessions and tours, Lennon usually slept for days afterwards.[77] When Lennon started filming How I Won the War in Almeria, Spain, he promised his wife and son they could join him there after two weeks of filming. The small apartment they were allocated was swiftly replaced by a villa when Ringo Starr and his wife joined them.[78]

Kenwood

Domestic life

The Beatles' accountant told Epstein the group members should move to houses near his in Esher, so Lennon bought a house called Kenwood in July 1964. It was a mock-Tudor-style house on three acres in Weybridge, where Cliff Richard already lived.[79] Lennon then spent twice the original £20,000 purchase price (equivalent to £431,200 in 2023)[36] on renovations for Kenwood,[80] reducing its 22 rooms to 17.[81] The new kitchen was so modern and complicated, someone had to be sent to explain how everything worked,[82] and during the extensive renovations the couple had to live in the attic bedroom for nine months.[83] Although Cynthia enjoyed entertaining in the larger rooms, Lennon could usually be found in a small sunroom at the back of the house overlooking the swimming pool, which was similar to his aunt's conservatory in Liverpool.[84] They had a cat called "Mimi", named after Lennon's aunt.[85] Cynthia took care of Julian herself, without a nanny, although babysitters were frequently employed. She also did the cooking herself, but employed a housekeeper, gardener, and chauffeur, who lived off the premises.[86]

When she passed her driving test, Lennon serially bought her a white Mini, a gold Porsche, a red Ferrari, and a green Volkswagen Beetle, usually as surprises without consulting her first.[87] Cynthia enjoyed the closeness of Pattie Boyd and Maureen Starkey (Ringo Starr's wife), as both lived nearby, often going on holiday together or shopping.[88] She was often photographed at Beatles' movie premieres and special occasions, and sometimes with Lennon and Julian at home, which meant she had the role of a Beatle wife, as well as being a mother. The Lennons often went to a nightclub in central London until nearly dawn, after which she took Julian to school.[89] Kenwood became the place to visit for the other Beatles, various American musicians, and total strangers who Lennon had met the previous night in London nightclubs.[88]

In 1965, she opened the front door of Kenwood to see a man who "looked like a tramp", but with her husband's features.[90] He explained that he was Alfred Lennon, the father whom Lennon had supposedly not seen for years.[91] Lennon was annoyed when he came home, telling her for the first time that his father had visited the NEMS office, Epstein's business, a few weeks before.[91] Three years after the meeting in the NEMS office, Alfred Lennon (who was then 56 years old) turned up at Kenwood again with his fiancée, 19-year-old student Pauline Jones.[92] He asked if the Lennons could give Pauline a job, so she was hired to help with Julian and the piles of Beatles' fan mail. Lennon's father and his fiancée then spent a few months living in the attic bedroom.[92] During an interview at Kenwood with Evening Standard reporter Maureen Cleave, Lennon said, "Here I am in my Hansel and Gretel house, famous and loaded, and I can't go anywhere. There's something else I'm going to do, only I don't know what it is, but I do know this isn't it for me".[93]

Drugs

Cynthia knew her husband took drugs like Preludin, and regularly smoked cannabis, but thought of them as not being very dangerous.[83] On 27 March 1965,[94] at a dinner party given by a dentist, John Riley,[95] the Lennons, Harrison, and Boyd were given LSD without their knowledge.[96] Although told not to leave the house, Harrison drove them to various nightclubs, with Riley following them by taxi.[94][97] At the Ad Lib club, they thought the lift up to the club was on fire and started screaming,[98] before finally crawling out of the lift for which Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, and Starr were waiting. Harrison later drove them back home in Boyd's Mini Cooper at no more than 10 mph, as he was also feeling the effects of the drug. They stayed up all night at Kenwood, experiencing the full effects of their first LSD trip.[99]

Lennon then started taking LSD on a regular basis in addition to his daily use of cannabis.[100] After much encouragement from him, Cynthia agreed to try LSD one more time, but the adverse effects were the same. Although she said at the time she would never take the drug again, she relented and took it for the last time a few weeks later, on the way to a party at Epstein's country house in Warbleton, East Sussex.[101] Although she hated the psychological effects of the drug, from this point she could see the change taking place in her husband: "It was like living with someone who had just discovered religion ... Tensions, bigotry, and bad temper were replaced by understanding and love".[102] In 1970, Lennon confessed he had probably taken LSD one thousand times since 1965, saying: "I used to just eat it all the time".[103] In the decades ahead, Cynthia would always maintain that John's drug use was the beginning of the end for the couple.[104][101]

By 1967, Lennon's aggressive edges from his childhood had disappeared, and he spent considerable amounts of time sitting in his sunroom or garden and daydreaming for hours on end.[105] He became somewhat uncommunicative towards most people, including Cynthia (but not with the other Beatles, who had an almost unspoken ability to understand one another).[105] Cynthia once complained, saying: "What I'd like is a holiday of our own ... John, Julian and me". Lennon replied with, "OK, I know, we'll all retire to a little cottage on a cliff in Cornwall, all right?" Then adding, "No, I've got these bloody songs to write. I have to work, to justify living."[106] She understood his temperament, but felt frustrated at never having developed her own career by using her art college background.[106]

India and Ono

The Beatles were scheduled to fly to India to visit the Maharishi for two or three months of Transcendental Meditation. Before they left, Cynthia found letters from Yoko Ono to Lennon which indicated he had been having contact with her over a period of some time.[107] Lennon denied he was involved with Ono, explaining that she was just some "crazy artist" who wanted to be sponsored, although Ono kept up a stream of telephone calls and visits to Kenwood.[108] On 15 February 1968,[109] the Lennons flew to India, followed by the other Beatles and their partners four days later:[110] Boyd, Asher, and Maureen Starkey.[111] The division between the sexes was emphasised by the male musicians sitting outside at night composing songs, while their partners gathered together in one of their rooms, often talking about life as the wife or partner of a Beatle.[112] The Lennons shared a four-poster bed at the ashram, with Lennon playing guitar and Cynthia drawing and writing poetry between their long sessions of meditation.[112]

"Magic Alex" (Greek-born Alex Mardas, who controlled Apple Electronics) arrived later, smuggling in alcohol from the nearest village as it was not allowed in the ashram. After two weeks, Lennon asked to sleep in a separate room, saying he could only meditate when he was alone.[113] Every morning, Lennon would walk to the local post office to see if he had received a telegram from Ono, who sent one almost daily. Cynthia found out about these secretive trips much later, saying: "I had thought our magical interlude with the Maharishi would be the making of our marriage – but in reality it just presaged the end".[114] Paul Saltzman later published a book of photographs, The Beatles in Rishikesh,[115] showing Lennon deep in thought, and Cynthia's confused expression.[116] Despite the alienation from Lennon, she later spoke about her time there, saying: "I loved being away from the fans, hordes of people, deadlines, demands and flashing cameras".[114]

Divorce

During the flight back to England,[112] Lennon got very drunk on Scotch and confessed that he had been involved with other women during their marriage.[117] He went on to detail his liaisons with groupies, friends (such as Joan Baez, actress Eleanor Bron, journalist Cleave) and "thousands" of women around the globe.[118] Although not wanting to hear Lennon's confession, she knew women were attracted to him, "like moths to a flame".[119] Two weeks later, in May 1968, Lennon suggested Cynthia take a holiday in Greece with Mardas, Donovan, and two friends, as he would be very busy recording songs for what would become the White Album.[120] She arrived back at Kenwood from Greece earlier than expected, at 4 o'clock on 22 May 1968,[121] to discover Lennon and Ono sitting cross-legged on the floor in matching white robes, staring into each other's eyes,[122] and then found Ono's slippers outside the Lennons' bedroom door.[123] Shocked, she asked Jenny Boyd and Mardas if she could spend the night at their apartment.[124] At the apartment Boyd went straight to bed, but she and Mardas drank more alcohol, with Mardas trying to convince her to run away together. After she had vomited in the bathroom, she collapsed on a bed in the spare bedroom, with Mardas joining her and trying to kiss her until she pushed him away.[125]

Lennon seemed absolutely normal when she returned home the next day, and steadfastly maintained his love for her and their son,[126] saying: "It's you I love Cyn ... I love you now more than ever before".[124] Lennon went to New York with McCartney shortly after,[127] but as Cynthia was specifically not invited, a trip to Pesaro, in Italy, was arranged with her mother.[124] After an evening with Italian hotelier Roberto Bassanini, Mardas was waiting at the hotel to break the news that Lennon was planning to sue for divorce on grounds of adultery, seek sole custody of Julian, and "send her back to Hoylake".[128] She said in 2005: "The mere fact that 'Magic Alex' [Mardas] arrived in Italy in the middle of the night without any prior knowledge of where I was staying made me extremely suspicious. I was being coerced into making it easy" ... [for Lennon and Ono] "to accuse me of doing something that would make them not look so bad."[129] As Lennon had initiated divorce proceedings, it prompted her to exclaim: "Suing me for divorce? On what grounds is he suing me?"[130] When the news of Ono's pregnancy broke, Cynthia started her own divorce proceedings against Lennon on 22 August 1968.[131]

Their decree nisi was granted on 8 November 1968.[132] The financial settlement was hampered by Lennon's refusing to offer any more than £75,000 (equivalent to £1,383,800 in 2023),[36][133] telling her on the phone that the payment was akin to winning the football pools and that she was not worth any more.[134] The settlement was then raised to £100,000 (equivalent to £1,845,000 in 2023),[36] £2,400 annually (equivalent to £44,300 in 2023),[36] and custody of Julian.[135] A further £100,000 was put into a trust fund which Julian would inherit at age 21, and until then his mother would receive the interest payments. The trust deed had a codicil which provided for any further children by Lennon, so when Sean Lennon was born in 1975, Julian's inheritance was cut to £50,000 (equivalent to £922,500 in 2023).[36][136]

Cynthia lived for a few months in a flat Starr owned at 34 Montagu Square, central London,[137] but returned to Kenwood as Lennon and Ono preferred to live there instead, rather than in isolated Weybridge.[138] Lennon and Cynthia had one last short meeting at Kenwood (with Ono alongside Lennon), where Lennon accused her of having an affair in India, saying she was no "innocent little flower".[139] McCartney visited her and Julian that year,[140] and on the way to Kenwood he composed a song in his head which later became "Hey Jude".[140] Talking about their divorce,[141] McCartney later said: "We'd been very good friends for millions of years and I thought it was a bit much for them suddenly to be personae non gratae and out of my life".[142] Cynthia recalled, "I was truly surprised when, one afternoon, Paul arrived on his own. I was touched by his obvious concern for our welfare ... On the journey down he composed 'Hey Jude' in the car. I will never forget Paul's gesture of care and concern in coming to see us."[143]

She was once asked if Lennon had written any songs about their time together, and answered: "It was too soppy when you were young to dedicate anything to anybody. Macho Northern men didn't do that in those days".[5] In contrast, Lennon said he wrote the 1965 song "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" about an affair he was having, but rendered it in "gobbledegook" so Cynthia would not know.[144]

.jpg.webp)

Subsequent life

On 31 July 1970, Cynthia married Bassanini, whom she had started dating after parting with Lennon;[145] the couple divorced in 1973.[146] She then opened a restaurant in Ruthin, Wales, called Oliver's Bistro, which also had a B&B above the premises. She enrolled her son into the Ruthin School and he later joined the local Combined Cadet Force.[147] During Lennon's separation from Ono in 1973–74, his partner at the time, May Pang, tried to get Lennon to spend more time with his son, forming a friendship with Cynthia in the process, which continued even after John Lennon and Yoko Ono were reconciled.[148] A meeting during this period was the last time Cynthia saw John.[104] Julian had been allowed to visit his father twice a year by himself but John Lennon complained that during his time with Pang his ex-wife also wanted to be present, saying "She [Cynthia] thought she could walk back in 'cos I wasn't with Yoko!" After his reconciliation with Ono, he complained again that his son was not being allowed to visit him.[149]

On 1 May 1976, Cynthia married John Twist, a television engineer from Lancashire.[150] She published a memoir during their time together, A Twist of Lennon, in 1978, about her life before and with Lennon and containing her own illustrations and poetry.[151][152] Lennon tried to stop the publication of the book after an excerpt was published in a newspaper.[153] Cynthia's memoir gained renewed interest and went to a third printing of 200,000 copies in the weeks after Lennon's death.[154] She and Twist separated in 1981 and were divorced in 1982.[155] She sold the Bistro and changed her name back to Lennon by deed poll, later commenting about why it was financially necessary, "Do you imagine I would have been awarded a three-year contract to design bedding and textiles [for Vantona Vyella in 1983] with the name Powell? Neither did they. When it is necessary to earn a living, it is necessary to bite the bullet and take the flack".[156][5]

She began a relationship with Liverpudlian chauffeur Jim Christie in 1981, who became her partner for 17 years as well as her business manager, living in Penrith, Cumbria.[157][158] She said at the time "Jim has never felt he's living in John Lennon's shadow. He's four years younger than me and wasn't really part of that whole Beatles' scene".[159] They later lived on the Isle of Man and then in Normandy for some years but separated in 1998.[104][158]

She had kept mementos of Lennon for years but began auctioning them off after his death.[160] This included a personally drawn Christmas card from Lennon to her, which fetched £8,800 at Christie's in August 1981.[161] With her finances in an unsteady state – she would say in 1999 that "Apart from John, the men I have fallen in love with have never been good at earning a living" – more of her memorabilia of Lennon went up for auction in 1991, including antiques from Kenwood.[158][157] She said at the time, "I've enjoyed these things for 30 years. But it's time for a change".[157] Another set of items, including some of Lennon's drug paraphernalia, brought over $60,000 for her in 1995.[162] She later said, "I think in life we collect so much baggage, when you have a clear-out, you send it to a car-boot sale, etc. My baggage was in demand and sold at Christie's. When you have to pay the bills, you're not proud and you can't take it with you".[5]

Over the years she entered some failed business ventures, including in 1988 a perfume named Woman[163][164] (after the 1980 John Lennon song) and, in April 1989, a restaurant named Lennon's—at 13/14 Upper St Martin's Lane, Covent Garden—which had menu items such as Rubber Sole (a play on the already-punning 1965 Beatles album),[157][158] as well as Sgt. Pepper's Steak and Penny Lane Pâté.[165] It had a short life as a business venture, as it was considered to be far too expensive.[166] She would later blame some of these efforts on the men in her life encouraging her.[158]

The Beatles' Hamburg days were the subject of the 1994 film Backbeat, with Jennifer Ehle portraying Cynthia Powell.[167] The film characterises Lennon and Cynthia's relationship as one that will eventually be doomed by their wanting different things from life but with Lennon not wanting to hurt her.[168] Cynthia later complained that the film made her out "as a clingy, dim, little girlfriend in a headscarf".[169] In another film covering the early years of the pre-fame Beatles, the 1979 Birth of the Beatles, she was portrayed by Wendy Morgan.[170] She was portrayed in 2000 television film In His Life: The John Lennon Story by Gillian Kearney; the negative aspects of John's treatment of her were not overlooked.[171] Cynthia was subsequently portrayed in the troubled, Ono-centric 2005 American musical Lennon, with her character – played by Julia Murney – gaining a little more prominence during one of the show's rewrites.[172][173] Her life had a more central role in the 2010 BBC Four film Lennon Naked, with Claudie Blakley playing the part.[174] Her character was absent from the 2009 British film Nowhere Boy, which purported to cover the story of Lennon from 1955 to 1960 but focused on his relationships with his aunt and mother.[175]

In 1995, Cynthia made her recording début with a rendition of "Those Were the Days" which, produced by McCartney, had been a number one hit for Mary Hopkin in 1968.[5] It failed to chart. Whilst she was living in Normandy, an exhibition of her drawings and paintings were displayed at Portobello Road's KDK Gallery in 1999.[158] By the 1990s, she was appearing at some Beatles conventions but appeared ambivalent about doing so.[5][157] At times she maintained she was moving on with her life and putting her Beatles past behind her and at other times seemed to embrace continued interest in that past as inevitable.[5][104][157][158] The Daily Telegraph said in a 1999 profile, "In essence, she is a suburban woman who – almost in spite of herself – got caught up with one of the most extraordinary men of modern times. More than 30 years since her marriage to John Lennon ended, she is as entangled as ever".[158]

Later years and death

.jpg.webp)

In 2002, she married Noel Charles, a Barbadian nightclub owner.[176] In September 2005, she published a new biography, John, re-examining her life with Lennon and the years afterwards, including the events following his death. Michel Faber, writing in The Guardian, said of the book: "John is Cynthia's attempt to prove how much more she was worth. In theory, the disclosures of Lennon's loyal partner from 1958 to 1968 cannot fail to be valuable. On the page, the potential withers".[133] Rachael Donadio in the New York Times said the book "paints the picture of a man wounded by the deaths of family and friends, and tells the difficult story of the domestic front during Beatlemania". "If there is to be a balanced picture of Dad's life, then Mum's side of the story is long overdue," Julian Lennon, the couple's son, writes in the foreword.[177] In 2006, she and her son attended the Las Vegas premiere of the Cirque du Soleil production of Love, which marked a rare public appearance with Ono.[178] In 2009, she and her son opened an exhibition of memorabilia at The Beatles Story exhibition in Liverpool,[179] and she and Pattie Boyd staged a first-ever joint appearance at the opening of the Cafesjian Center for the Arts in Yerevan, Armenia.[180] On 30 September 2010, Julian opened his "Timeless" exhibition of photographs at the Morrison Hotel Gallery in New York. In attendance were Cynthia, Ono, Sean, and Pang, which was the first time all five had been in the same room together.[181]

The John Lennon Peace Monument was unveiled by Cynthia and Julian at a ceremony in Chavasse Park, Liverpool, on 9 October 2010 to celebrate the anniversary of Lennon's 70th birthday.[182] Cynthia lived with her husband, Noel, on the Spanish island of Majorca[179] until his death on 11 March 2013.[183]

She died on 1 April 2015 at her home in Majorca, at the age of 75 following a brief bout with cancer, her son Julian by her side.[184][185] Public messages of condolence were made by McCartney and Starr, with McCartney saying "She was a lovely lady who I've known since our early days together in Liverpool. She was a good mother to Julian and will be missed by us all", and Starr saying "Peace and love to Julian Lennon God bless Cynthia".[185] Ono also issued a statement, emphasising the position she held in common: "Being a single parent of a strong and intelligent boy is never easy. Cynthia and I understood each other in that way, wishing well for our sons and their future."[186] Beatles biographer Hunter Davies, who had spent considerable time with her and Lennon in the 1960s while researching his book, remembered her as "a lovely woman ... She was totally different from John in that she was quiet, reserved and calm."[185]

References

- Lennon 2005, p. 13.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 16–17.

- Lennon 2005, p. 14.

- Davies 1968, p. 57.

- "You ask the questions". The Independent. 7 July 1999. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Lennon 2005, p. 15.

- Harry 2000, p. 266.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 28.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 27.

- Spitz 2005, pp. 154–155.

- Lennon 2005, p. 22.

- Anderson 2010, p. 31.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 24–25.

- Lennon 2005, p. 27.

- Mulligan 2010, p. 23.

- Lewisohn 2013, p. 1291.

- Spitz 2005, p. 156.

- "Cynthia Lennon – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 1 April 2015. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Spitz 2005, p. 155.

- Cross 2004, p. 9.

- Clayson 2003, p. 31.

- "Living with Lennon". BBC. 21 May 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Edmondson 2010, p. xvii.

- "Lennon's friends recall ex-Beatle". BBC News. 25 November 2005. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Miles 1997, pp. 48–49.

- Davies 1968, pp. 58–59.

- Kane 2007, p. 55.

- Davies 1968, p. 100.

- Spitz 2005, p. 80.

- Cross 2004, p. 33.

- Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 46.

- Miles 1997, p. 59.

- Mulligan 2010, p. 57.

- Spitz 2005, p. 132.

- Spitz 2005, p. 313.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- Lennon 2005, p. 99.

- Salewicz 1987, p. 130.

- Coleman 1984, p. 173.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 47.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 122–124.

- Edmondson 2010, p. xviii.

- Spitz 2005, p. 348.

- Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 83.

- Davies 1968, pp. 173–174.

- Spitz 2005, p. 349.

- Dewitt 1985, p. 246.

- Cross 2004, p. 67.

- Loker 2009, p. 114.

- Barrow 2006, p. 94.

- Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 93.

- Mulligan 2010, p. 58.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 51.

- "Cynthia Powell Lennon". Lennon by Lennon Ltd. 2004. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- Wiener 1991, p. 51.

- Barrow 2006, p. 38.

- Ryan 1982, p. 153.

- "John Lennon Interview: Playboy 1980 (Page 2) – Beatles Interviews Database". www.beatlesinterviews.org.

- Carr & Tyler 1975, pp. 16–20.

- Carr & Tyler 1975, p. 25.

- Davies 1968, p. 226.

- Spitz 2005, p. 412.

- Loker 2009, p. 123.

- Lennon 2005, p. 271.

- Womack & Davis 2006, p. 109.

- Miles 1997, p. 103.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 172–173.

- Spitz 2005, p. 436.

- Spitz 2005, pp. 460–462.

- Barrow 2006, p. 80.

- Lennon 2005, p. 180.

- Davies 1968, p. 219.

- Spitz 2005, p. 514.

- Davies 1968, pp. 214, 228–229.

- Davies 1968, p. 358.

- Loker 2009.

- Anderson 2010, p. 62.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 254–255.

- Miles 1997, pp. 166–167.

- Tremlett 1975, p. 53.

- Miles 1997, p. 168.

- Miles 1997, p. 169.

- Spitz 2005, p. 548.

- Miles 1997, p. 143.

- Thomson & Gutman 2004, p. 73.

- Davies 1968, pp. 323–326.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 166–167.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 204–206.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 209–211.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 80.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 239–240.

- Spitz 2005, p. 739.

- Cleave, Maureen (5 October 2005). "The John Lennon I knew". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Cross 2004, p. 107.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 81.

- Herbert, Ian (9 September 2006). "Revealed: Dentist who introduced Beatles to LSD". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Mann 2009, p. 21.

- Cross 2004, p. 148.

- Spitz 2005, p. 566.

- Spitz 2005, pp. 665–666.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 244–248.

- Tillery 2010, p. 53.

- Wenner 1971, p. 76.

- Smith, Julia Llewellyn (25 July 2000). "I'm trying to make Julian feel that John did love him, even if he can't tell him any more". Daily Express.

- Davies 1968, pp. 328–329, 334–335, 384.

- Davies 1968, pp. 337–338.

- Spitz 2005, p. 740.

- Spitz 2005, pp. 740–741.

- Loker 2009, p. 280.

- Spitz 2005, p. 750.

- Anderson 2010, p. 74.

- Mulligan 2010, p. 105.

- Spitz 2005, p. 755.

- Lennon, Cynthia (10 February 2008). "The Beatles, the Maharishi and me". The Times. p. 1. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Roy, Amit (27 March 2005). "Long and Winding Road to Rishikesh". The Telegraph. Kolkata. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- Kane 2007, p. 61.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 101.

- Spitz 2005, p. 758.

- Kane 2007, p. 56.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 281–282.

- Mulligan 2010, p. 108.

- Ryan 1982, p. 155.

- Spitz 2005, p. 772.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 102.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 288–289.

- Spitz 2005, p. 773.

- Mulligan 2010, p. 106.

- Coleman 1999, p. 464.

- Hunt, Chris (December 2005). "The Loves Of John Lennon". Lennon: The Life – The Legend – The Legacy: 25th Anniversary Issue. Uncut Legends.

- Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 273.

- Mulligan 2010, p. xxii.

- Spitz 2005, p. 800.

- Faber, Michel (8 October 2005). "Imagine all the butties". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Coleman 1999, p. 467.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 113.

- Cross 2004, p. 195.

- Cross 2004, p. 184.

- Edmondson 2010, p. 107.

- Lennon 2005, p. 300.

- Spitz 2005, p. 782.

- Edmondson 2010, p. xxxii.

- Miles 1997, p. 465.

- Kehe, John (17 June 2012). "Paul McCartney: 40 career highlights on his birthday". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Wenner 1971, p. 226.

- Lennon 2005, p. 293.

- Sweeting, Adam (2 April 2015). "Cynthia Lennon obituary". The Guardian.

- "Cynthia Lennon". BBC. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 336–340.

- Harry 2000, p. 334.

- Lennon, Cynthia (2006). John. Translated by Iván Morales. Teia, Barcelona: Ma Non Troppo. pp. 236–237. ISBN 84-96222-74-8. OCLC 76858240.

- "Life with The Beatles". BBC News. 27 August 1999. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- "Cynthia Powell". lambiek.net. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- Ingham 2003, p. 349.

- "'Instant' books focus on Lennon". Ottawa Citizen. Reuters. 30 December 1980. p. 38. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "Names in the News: Cynthia Lennon Twist". The Daily Times. Portsmouth, Ohio. Associated Press. 14 September 1981. p. 10.

- Lennon 2005, pp. 374.

- "Goodbye to All That: Cynthia Lennon Sells What John Left Behind". People. 2 September 1991. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Moir, Jan (28 May 1999). "I want John out of my life". The Daily Telegraph.

- "The Linda McDermott interview: Cynthia Lennon". merseyworld.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- Lennon 2005, p. 285.

- Badman 2001, p. 287.

- "Names in the News: John Lennon". Kingman Daily Miner. Associated Press. 8 September 1995. p. 1B.

- "On Tuesday, April 05, 1988, a U.S. federal trademark registration was filed for CYNTHIA LENNON". Trademarkia, Inc. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- "Perfume Intelligence – The Encyclopaedia of Perfume". Perfume Intelligence. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- Badman 2001, p. 421.

- Badman 2001, p. 225.

- "Backbeat (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- Seibert, Perry. "Backbeat: Critics' Reviews". Rovi Corporation. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Anthony, Andrew (16 October 2005). "Imagine? Not here". The Observer. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- "Birth of the Beatles (1979)". BFI. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- Oxman, Steven (30 November 2000). "Review: 'In His Life: The John Lennon Story'". Variety.

- Kozinn, Allan (31 July 2005). "The Many Faces of John Lennon: Black, White, Male, Female". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- Hernandez, Ernio (August 2005). "Behind the Musical: Nine Johns Come Together for Broadway's Lennon". Playbill. Archived from the original on 22 August 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "Lennon Naked: Characters". PBS Masterpiece. PBS. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- Blackie, Andrew (21 January 2010). "An Interesting Proposition with 'Nowhere' Much to Go". PopMatters. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "Cynthia Lennon: The first wife of John Lennon whose steadfastness was". Independent.co.uk. April 2015.

- Donadio, Rachel (18 December 2005). "Inside the List". The New York Times.

- Thompson, Jody (1 July 2006). "All you need is Love: Beatles show hits Vegas". BBC News. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- Brooks, Richard (13 June 2009). "Julian Lennon gives family peace a chance". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Titizian, Martia (14 November 2009). "Cynthia, Pattie, and the Beatles". The Armenian Reporter. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- "Julian Lennon: 'Timeless' exhibition at Morrison Hotel Gallery". Yoko Ono. 30 September 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Monument to John Lennon unveiled in Liverpool on his '70th birthday'". The Daily Telegraph. 9 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Obituary: Cynthia Lennon - the beautiful Wirral student who caught John's eye". April 2015.

- "In Loving Memory – Cynthia Lennon – 1939–2015". julianlennon.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "John Lennon's first wife Cynthia dies from cancer". BBC News. 1 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Yoko Ono Remembers Cynthia Lennon: 'She Embodied Love and Peace'". Rolling Stone. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

Sources

- Anderson, Jennifer Joline (2010). John Lennon: Legendary Musician & Beatle (Lives Cut Short). ABDO Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-60453-790-1.

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After The Break-Up 1970–2001. Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-7520-5.

- Barrow, Tony (2006). John, Paul, George, Ringo and Me. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-882-7.

- Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (2002). The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of the Beatles (Reprint ed.). NAL Trade. ISBN 978-0-451-20735-7.

- Carr, Roy; Tyler, Tony (1975). The Beatles: An Illustrated Record. Harmony Books. ISBN 0-517-52045-1.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). John Lennon (Beatles). Sanctuary Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86074-451-8.

- Coleman, Ray (1984). John Winston Lennon: 1940–66 v. 1. Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-283-98942-1.

- Coleman, Ray (1999). Lennon: The Definitive Biography (Revised ed.). Harper Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-06-098608-7.

- Cross, Craig (2004). Day-By-Day Song-By-Song Record-By-Record. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-31487-4.

- Davies, Hunter (1968). The Beatles: The Authorized Biography (paperback). Dell Publishing. Also adapted for publication in Davies, Hunter (13–20 September 1968). "The Beatles". Life.

- Dewitt, Howard A. (1985). The Beatles: Untold Tales. Horizon Books. ISBN 978-0-938840-03-9.

- Edmondson, Jacqueline (2010). John Lennon: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-37938-3.

- Harry, Bill (2000). The John Lennon Encyclopedia. Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0404-8.

- Ingham, Chris (2003). The Rough Guide to The Beatles. Rough Guides Ltd.

- Julien, Oliver (2009). Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles: It Was Forty Years Ago Today. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6708-7.

- Kane, Larry (2007). Lennon Revealed. Running Press. ISBN 978-0-7624-2966-0.

- Lennon, Cynthia (1978). A Twist of Lennon. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-352-30196-3.

- Lennon, Cynthia (2005). John. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-89512-2.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2013). The Beatles: All These Years, Vol. 1: Tune In. Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-1-4000-8305-3.

- Loker, Bradford E. (2009). History with The Beatles. Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60844-039-9.

- Mann, John (2009). Turn on and Tune in: Psychedelics, Narcotics and Euphoriants. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84755-909-8.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Many Years From Now. Vintage-Random House. ISBN 978-0-7493-8658-0.

- Miles, Barry; Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- Mulligan, Kate Siobhan (2010). The Beatles: A Musical Biography (Story of the Band). Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-37686-3.

- Ryan, David Stuart (1982). John Lennon's Secret: A Biography. Kozmik Press. ISBN 978-0-905116-08-2.

- Salewicz, Chris (1987). McCartney. Futura Publications. ISBN 978-0-7088-3374-2.

- Sheff, David (2000). All We Are Saying. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-25464-3.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles – The Biography. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-80352-6.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-2684-6.

- Thomson, Elizabeth; Gutman, David (2004). The Lennon Companion. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81270-5.

- Tillery, Gary (2010). The Cynical Idealist: A Spiritual Biography of John Lennon. Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-0875-6.

- Tremlett, George (1975). The Paul McCartney Story. Futura. ISBN 978-0-86007-200-3.

- Wenner, Jann (1971). Lennon Remembers: The Rolling Stone Interviews (paperback). Popular Library.

- Wiener, Jon (1991). Come Together. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06131-8.

- Womack, Kenneth; Davis, Todd F. (2006). Reading the Beatles. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6715-2.