Crow Canyon Archaeological District

The Crow Canyon Archaeological District is located in the heart of the Dinétah region of the American Southwest in Rio Arriba and San Juan counties in New Mexico approximately 30 miles southeast of the city of Farmington.[2] This region, known to be the ancestral homeland of the Navajo people, contains the most extensive collection of Navajo and Ancient Pueblo petroglyphs or rock art in the United States. Etched into rock panels on the lower southwest walls of the canyon are petroglyphs or rock art depicting what is believed to be ceremonial scenes and symbolic images that represent the stories, traditions and beliefs of the Navajo people. Dating back to the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the petroglyphs have maintained their integrity despite the environmental conditions of the canyon and the effects of tourism. Among the ruins in the Crow Canyon Archaeological District there is also a cluster of Navajo defensive structures or pueblitos, which were built in the 18th century during periods of conflict with the Utes and the beginnings of Spanish Colonialism.[3][4]

Crow Canyon Archeological District | |

Rock art at Crow Canyon | |

| Nearest city | Farmington, New Mexico |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°32′49″N 107°37′00″W |

| Area | 3,200 acres (1,300 ha) |

| Architectural style | Hogans & Pueblitos |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001200[1] |

| NMSRCP No. | 276 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 15, 1974 |

| Designated NMSRCP | March 20, 1973 |

Crow Canyon Archaeological District was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[1]

Geography and topography

Crow Canyon is located in the center of Dinétah, the ancestral home of the Navajo people. Dinétah, is located in what is known as the Four Corners Region of the United States. The region covers a large part of northwestern New Mexico , southeastern Utah, southwestern Colorado and northeastern Arizona and is surrounded by four mountains standing at each of the cardinal directions. The mountains, considered to be sacred by the Navajo people, are Hesperus Peak (North), Mount Taylor (South), Blanca Peak (East) and the San Francisco Peaks (West). Nestled within these mountains stand three more sacred mountains, Huerfano Mesa, Gobernador Knob, and Navajo Mountain. Crow Canyon is a remote area located in the heart of the mountains.

Low, arid desert landscape, high cliffs, deep canyons and mesas made of sandstone surround the heart of Crown Canyon. Natural erosion resulting from wind and water has carved many irregular rock formations throughout the area.

Navajo history, language and culture

The foundations for the Navajo culture were well established and date back to the years 1100 -1500 A.D. The ancestry of the Navajo people can be traced back to Asiatic origins, specifically, the Siberian Highlands, the region inhabited by the Mongols. In Asia, small groups broke off from existing populations and crossed the Bering Strait into North America where they eventually settled in areas of Alaska and Canada and eventually migrated to the Dinétah region of the American Southwest. The Navajo Nation is currently the second largest tribe in the United States.

The linguistic origins of the Navajo people trace back to the Alaskan Athabaskans who are the Native Alaskan people. The Navajo speak a form of Na-Dené, which is the language spoken by the Southern Athabaskan people.

The culture of the Navajo people has a rich history of symbolism, spirituality, and has a deep connection to the Earth. Beginning with the Navajo creation story, colors have both symbolic and spiritual meaning to the Navajo. There are four colors that are considered sacred by the Navajo people. Black, white, yellow and blue represent each of the sacred mountains surrounding the Navajo in the Dinétah region. In keeping with this, the number four also has special significance to the Navajo, exemplified by the importance of the four cardinal directions, four seasons, first four clans, and rituals that include four songs.

The restoration of harmony in the body is central to Navajo healing. The role of the medicine man is still an active part of Navajo healing. Using methods such as herbs, chants, songs and prayers, the medicine man will also approach healing through supernatural and spiritual forces. The majority of Navajo people prefer to receive more traditional hospital care in hospitals within the Navajo Nation, but will augment healing with traditional methods.

Family is of central importance to the Navajo people and the traditional Navajo society was established through matrilineal lineage The Navajo family is based on the traditional domestic unit surrounded by homes of extended family. Navajo children are raised with an ample amount of freedom as a sign of respect for their integrity.

Crow Canyon petroglyphs

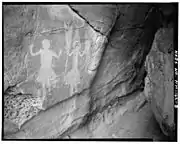

The Crow Canyon Archaeological District contains one of the most well known and extensive collections of Navajo petroglyphs in the United States. The south-facing wall of the canyon consists of 44 rock art panels depicting clusters of hundreds of the earliest Navajo petroglyphs known to date. The petroglyphs are believed to have had powerful ceremonial and symbolic meaning to the Navajo people. Many similarities have been observed between the images that are represented in the petroglyphs and the ceremonial sand paintings of the Navajo people. Discovered among the petroglyphs, are also Anasazi images from the early Ancestral Pueblo people. The Anasazi were the ancient ancestors of the modern-day Pueblo people of New Mexico and Arizona. They are known to be cliff dwellers that inhabited the area from AD100 to approximately, AD1600,[5] indicating that this area was inhabited prior to the settling of the Navajo people.[6]

The petroglyphs were thought to be carved into the rock panels using stone, bone, wood or possibly even knives or sharp metal tools. Residues of paint that have been analyzed in the area indicate that the colors were made from local resources available such as minerals and plants.[7][8]

Hundreds of images representing animals, plants, corn, bow and arrows, spears, warriors, hunting scenes, supernatural beings, and representations of traditional Navajo art can be found on the 44 panels. A number of petroglyphs are believed to depict images of every day Navajo life, as well as images that are representative of the Navajo creation story and religious and spiritual ceremonies. Among the images are found, two male Shaman or deities. One deity is depicted with feathers on his back, horns, and a staff and the other is wearing a headdress with bow and a rattle in his hands. What is believed to be a female deity is also represented, its style being a more traditional Navajo geometric image.[1] Buffalo and elk impaled by arrows and corn stalks growing out of rain clouds symbolize the hunt and the central importance of corn in the lives of the Navajo people, both symbolic of a hunter-gatherer culture. A number of petroglyphs are thought to depict everyday life of the Navajo among images connected to the Navajo creation story and religious or spiritual ceremonies.

Crow Canyon pueblito and the pueblitos of Dinétah

A pueblito, which is the Spanish word for, "little or small village", is an earthen and stone structure built above ground, on tops of large boulders, mesas or in discreet locations against canyon walls. Over 100 pueblitos have been discovered by archaeologists in the Dinétah region of the American Southwest. The number of pueblitos erected across the region is indicative of an extremely tumultuous period in the history of the Navajo and Pueblo people and their neighboring tribes. Attacks by the Spanish from the East and South and the Utes from the North, were a constant threat to the Navajo people. The Utes were a threat to both the Navajo people and the Spaniards. During Ute raids, horses, guns, woman and children would be confiscated. The women and children were sold or traded as slaves or,"Genízaros" in New Mexico and were very profitable for the Utes.

As a result of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and the Spanish Reconquest of 1692,[9] many Pueblo tribes left their homes in the Rio Grande Valley to find safety with the Navajo people. The Crow Canyon pueblito is one of a network of defensive sites or pueblitos located in the Dinétah region. These sites were inhabited by the Navajo people and also served as refugee centers for other tribes fleeing from the oppression of Spanish colonialism.

The Crow Canyon pueblito which is located just below the south ridge of the canyon, offered a unique vantage point and a defensive advantage. The pueblito was strategically positioned as part of an extensive communication system in which different Navajo and Pueblo tribes could give warning of oncoming raids and threats. The pueblito itself consisted of four rooms. An additional, detached room, strategically situated on top of a large boulder, was specifically designed and used for defensive purposes and as an outlook post.

The ruin of the defensive structure currently stands just over six feet in height with very steep sides which made it easier to defend upon attack. The West Wall of the structure has entirely collapsed and there are partial remains of walls in the ground level rooms, but the passage of time has left its mark.[10] Other structures at the site include, roof beams, the remains of eight forked-pole hogans, two sweat lodges and several areas that were designated for grain storage.[11]

These strategies lasted until approximately the year AD1780 when the threat of attack coupled with a long drought forced the Navajo to leave the pueblitos of their homeland and retreat further south and west.[12]

Examples of other pueblito ruins in the Four Corners region include, Frances Canyon Ruin, Tapacito Ruin, Largo School Ruin, Simon Canyon Ruin, Split Rock Ruin and Hooded Fireplace Ruin.[13]

Archaeology at Crow Canyon

Pueblitos were thought to be temporary habitations during times of regional turmoil. Because of this, the artifacts found at pueblito sites are not as numerous as they would be in more permanent Pueblo villages or hogan villages that the Navajo people traditionally live in.[14]

Ceramic pottery assemblages and lithics found at Crow Canyon archaeological site are dated from the Dinétah phase (AD 1500-1630) and the Gobernador Phase (AD 1650-1777),[15] indicating that the site had different phases of habitation. Dinétah gray, Gobernador polychrome, Acoma Red and Jemez Black-on-white were used in the painting of the pottery, the latter two indicative of cultural and artistic contributions of other Pueblo groups.[16]

Dendochronology or tree ring analysis has been completed on samples from the Crow Canyon site. Unfortunately, there has been no conclusive results regarding the date of construction of the Crow Canyon pueblito through tree-ring analysis..[14] Dr. Ronald Towner has done extensive archaeological research in the Dinétah region using tree-ring analysis and indicates in his study in 1997 that masonry structures are dated to correspond with the period of Ute attacks in the Dinetah region. However, tree ring analysis and other archaeological data collected from various pueblito sites in the Dinétah region do not align with the temporal framework of a Puebloan immigration or a Spanish Conquest.[17] It is, however, known that the Crow Canyon pueblito was inhabited on or about the year AD1723.[16] The analysis indicates the use of pinyon and juniper wood in the immediate area of the site.

Tourism and preservation

The Crow Canyon Archaeological District is among the more remote and hard to access areas of the American Southwest. It is estimated that it is approximately twenty miles to the nearest paved road. A four-wheel drive vehicle is recommended to those visiting, especially after periods of rain.[18] Because of the difficulty of access, Crow Canyon has fewer visitors than other petroglyph sites in the American Southwest.

The National Park Service has guidelines that must be strictly adhered to when accessing culturally and historically significant areas throughout the United States. It is always recommended that hands are kept away from the petroglyphs and rock art panels. The natural oils from human hands are destructive to petroglyphs and over time, will darken them, making them more difficult to see. Staying on the trails, which are well defined, is extremely important. Climbing the surrounding rocks can dislodge rock material that can damage the integrity of the petroglyph panels. As these lands are considered sacred by the Navajo people, an attitude of respect and care must be maintained to preserve the site for future generations.[19]

See also

,

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Crow Canyon Petroglyphs". www.blm.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- "The Spanish and the Navajo". navajopeople.org. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- "Post-Pueblo: Navajo History & Culture | Peoples of Mesa Verde". www.crowcanyon.org. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- "Ancestral Pueblo culture | North American Indian culture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "The Anasazi [ushistory.org]". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "Navajo Petroglyphs | Navajo Code Talkers". Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- "Native American Symbols, Pictographs & Petroglyphs – Legends of America". www.legendsofamerica.com. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- Hirst, K. Kris. "The Great Pueblo Revolt - Resistance Against Spanish Colonialism". ThoughtCo. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- "Crow Canyon Pueblito". www.aztecnm.com. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Crow Canyon Pueblito". www.aztecnm.com. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- "Northwestern New Mexico's Pueblitos, a Navajo Legacy - DesertUSA". www.desertusa.com. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- "Defensive Sites of Dinétah". www.blm.gov. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- "Pueblitos of the Dinétah". Archaeology Southwest. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- Towner, Ronald. "Dendroarchaeology and Early Dinetah Navajo Social Organization".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Crow Canyon Pueblito". www.aztecnm.com. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Towner, Ronald Hugh (1997). "The dendrochronology of the Navajo pueblitos of Dinetah".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Crow Canyon Petroglyphs". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- Albuquerque, Mailing Address: Headquarters Administration Offices 6001 Unser Blvd NW; Us, NM 87120 Phone:899-0205 x335 Contact. "Common Etiquette for Visiting a Petroglyph Site - Petroglyph National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

External links

- Crow Canyon petroglyphs, 26 photographs from Historic American Buildings Survey