Crosbie Castle and the Fullarton estate

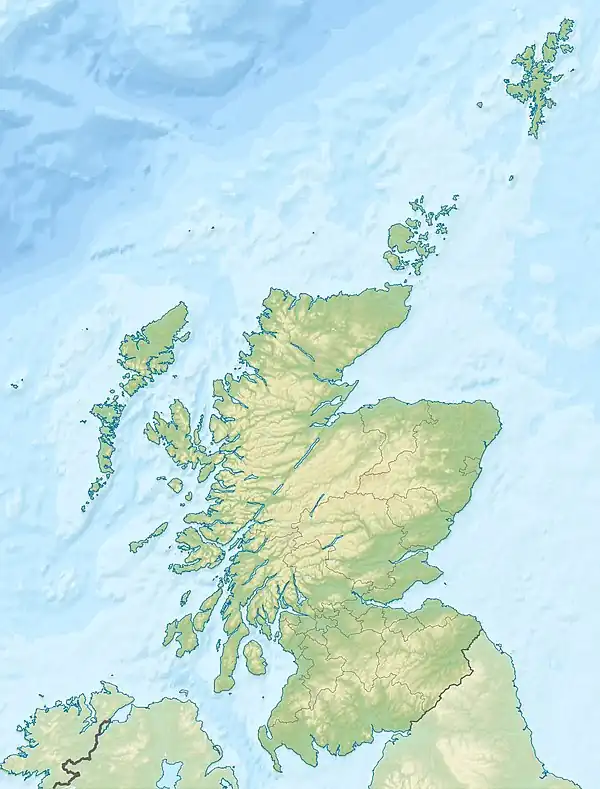

Crosbie Castle (NS 343 300) and the Fullarton estate lie near Troon in South Ayrshire. The site was the home of the Fullarton family for several centuries. The lands were part of the feudal Barony of Corsbie Fullartoune (sic).[1] The Crosbie Castle ruins were eventually used as an ice house after the new Fullarton House mansion was built. The mansion house was later demolished and the area set aside as a public park and golf course.

| Crosbie Castle | |

|---|---|

| Fullarton, Troon, South Ayrshire, Scotland UK | |

Crosbie Castle ruins | |

Crosbie Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55.54°N 4.66°W |

| Site information | |

| Owner | South Ayrshire Council |

| Controlled by | Crawford clan |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 16th century |

| Built by | Crawfords |

| In use | Until 18th century |

| Materials | stone |

Crosbie Castle

Robert II ( Robert II only came to the throne in 1371 and so this grant is questionable in 1344) granted the old Crosbie estate to the Fullartons in 1344 and by the eighteenth century the old castle was partly demolished and converted into an ice house for Fullarton House, with a doocot nearby.[2] In 1969 more of the ice house was demolished to make it safe and the doocot was raised to ground level. The building had been known as Crosby Place and later became Fullarton House, not long before the new building of the same name replaced it.[3]

The castle is known to have been rebuilt at least three times over the years, following the standard square form as seen throughout Ayrshire. The ruins today mainly represent the dungeon of the old castle. In the days of the laird's right of pit and gallows criminals would be held there before sentence was passed on them by the barony court. Many of Crosbie Castle's stones were used in the construction of the first Fullarton House. The old castle dungeon had an underground stream, making it the ideal cold storage cellar or ice house.[4]

Close sees it as having similarities with Monkcastle near Dalry.[5]

Another Crosbie Castle or tower is located in West Kilbride, North Ayrshire.

Views of Crosbie Castle ruins

A corner of the old tower castle walls.

A corner of the old tower castle walls. Marriage stone of William Fullarton and Anne Brisbane.

Marriage stone of William Fullarton and Anne Brisbane. The old Ice House constructed from the ruins of Crosbie Castle.

The old Ice House constructed from the ruins of Crosbie Castle. The old entrance and spiral staircase at the Ice House / Crosbie Castle.

The old entrance and spiral staircase at the Ice House / Crosbie Castle.

Crosbie church and cemetery

The church, at the edge of Fullarton Park (NGR NS 34427 29488) was first recorded in 1229, the present structure dates from 1691. William Roy's map records the name as Crosbay[6] and Corsby is another variant. Tradition claims that the roof blew off and the gable damaged on the same day in 1759 that Robert Burns was born in Alloway and it was left as a ruin.

It was disjoined from the parish of Dundonald in 1651 and annexed to the united parishes of Monkton and Prestwick. In 1688 Crosbie was joined again with Dundonald parish; after which it was rarely used.[7] One of the graves, recarved in the nineteenth century, is that off David Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh, son of James, alleged assassin[7] of the 'gude' Regent Moray, bastard son of James V. This event occurred in 1570 and David is said to have died in 1619; however Hamilton of Wishaw gives his death as being in 1613.[8] In 1545 John Hamilton, Abbot of Paisley, gave David Hamilton, his kinsman, the lands of Monktonmains near Prestwick in fief. The family lived at Overmain House for three generations, the house later being renamed 'Fairfield'.[9] David Fullarton had married David Hamilton's sister.[10]

The inscription reads:

|

Heir lye corpis of ane honorabel man callt |

Janet McFadzean was buried in Crosbie cemetery in 1761 and the front of her tombstone reads: Here lyes the corps of Janet McFadzean, Spous of William McFadzean, Quarter-Master Sergean in Lovetenan General Homs Regiment of Sol., who died August 22, 1761, aged 27 years.

The reverse side reads:

|

Twenty-four years i lived a maiden life, |

Carvings on a recess within the North wall record that this is also the burial place of the family and lairds of Fullarton of that Ilk until the family established a family burial plot at Irvine's Old Parish Church. Colonel Fullarton was buried in Isleworth Church in Surrey, but he is commemorated at Irvine.[11]

Constructed on the site of the original chapel, this was a chapel-of-ease of the Fullartons, the name Crosbie itself comes from the Anglo-Saxon word 'Crossbye', signifying the dwelling place of the cross; a fairly common placename; a Crosbie Tower survives near West Kilbride, a Crosby is near Maryport in Cumberland, also Crosby upon Eden, and High and Low Crosby in that county; Little Crosby in Lancashire; Crosby Garret (Westmorland), etc. Crosby is also a fairly common surname.[12]

The cemetery dates from circa 1240 and was held by Fullarton of Crosbie in the fourteenth century after being passed on from relatives. Records indicate that this ground was used by a holy order before the Fullartons arrived in the area.[4] The chapelry of Crosbie, together with that of Richardstoun (Riccartoun) were attached to Dundonald and were granted by the second Walter the Steward to the short-lived Gilbertine Convent which he had founded at Dalmulin before 1228. The convent was dis-established in 1238 and the chapel passed to the monks of Paisley Abbey.[13][14]

Robert Burn was the last Carmelite prior in Fullarton and is recorded as a post-reformation 'reader at Dundonald and Crosbie'.[15]

A village once clustered around the church.[7] The cemetery was the burial ground for Troon until 1862 and family lairs were still in use until after the First World War. On the other side of the road, the remains of the church manse can still be seen (2009). The 'Wrack Road' was the Fullarton Estate estate road used by tenants who took their carts down to the shore to collect seaweed or wrack as fertilizer and it was the main road from Troon for funerals going to Crosbie.[4]

Loans village was once part of the Fullarton Estate. Old maps show that a small loch, the Reed Loch, was located on the estate near Lochgreen House. Part of the loch was retained as a curling pond for many years, however it has now been entirely drained (datum 2012).

Views of the cemetery

Crosbie church gates.

Crosbie church gates. Church and cemetery.

Church and cemetery. David Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh's gravestone.

David Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh's gravestone. The inscription on David Hamilton's gravestone.

The inscription on David Hamilton's gravestone.

An epistle by John Laing suggests that Crosbie Kirk is haunted:

|

But sir, sin' I maun let you know An' comin' hame, the truth to tell, Deed Sir, I've often heard it tell, |

Fullarton House and estate

Fullarton House was built by William Fullarton of that Ilk in 1745 and altered by his son, however it was demolished in 1966 by the council who had been unable to maintain the building after purchasing it in 1928. The stables had been built in the 1790s and were converted to flats in 1974.[17]

The entrance route had been changed by William Bentinck, Duke of Portland and the house design altered so that the back became the front, with grand views opened up of the Isle of Arran and Firth of Clyde.[3] Originally there were four pillars at the rear of the polices, two of which were gate posts, and the two others are said to have held stone hawks which were a sign of the fowlers' profession.[18] After centuries of occupation the Fullarton lines possession had thus come to an end when the Duke of Portland purchased the property in 1805. He lived here for a while as his principal residence in Scotland, however he had a greater interest in developing Troon harbour and the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway.

The grounds are now a park with some signs of the old house still apparent, such as the magnificent stable block, the ornamental pediments, walled gardens, doocot fragments and an ice house.[2] A thatched lodge called Heather House stood at the entrance to the house until it burned down in the 1950s.

The Fullarton family

The name is thought to come from the office of 'Fowler to the King', the purpose of which was to supply wild-fowl to the King as required. The dwelling which came with the post was called Fowlertoun and the family may have eventually adopted the name. The Fullartons of Angus had been required by Robert I to supply him with wildfowl at his castle of Forfar.[3]

Alanus de Fowlertoun was in possession of the lands shortly before his death in 1280 and the family continued in a nearly unbroken line from father to son. The family house had originally been located in the area closer to the shore, presently named Fullarton Drive, however as the population of the village started to grow, the decision was made to relocate 2 miles east. The family had given lands, the Friars Croft, to the Carmelite friars and George Foullertoun held the lands from 1430 to 1471 and was often known as the Laird of Crosbie; he may have moved the family to Crosbie prior to Fullarton House being built.[19]

James Fullarton of Fullarton and Crosbie, received on 20 November 1634, a commission under the great seal, from King Charles I, appointing him sheriff of the bailiery of Kyle Stewart.[20] William Fullarton, the builder of the house, inherited the estate from his grandfather in 1710, he having inherited it from his brother in turn.

Orangefield and Fairfield near Monkton, Ayrshire had been part of the Fullarton Estate, however they were sold by Colonel William Fullarton circa 1803, prior to his taking up an official appointment in Trinidad as one of the government's commissioners.[21]

Colonel Fullarton died in 1808, the last Fullarton of that Ilk laird.[3] He wrote in 1793 the seminal A General View of the Agriculture in the County of Ayr and was one of the few on record to praise Robert Burns's skills as a farmer, commenting favourably on a method of dishorning cattle which the poet had demonstrated. Burns is said to have visited Fullarton. Napoléon III, as Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (20 April 1808 – 9 January 1873) stayed at the house whilst attending the Eglinton Tournament of 1839.[22] Burns made a complimentary reference to Colonel Fullarton in 'The Vision'. The Colonel certainly visited Burns at Ellisland in 1791.[23]

Colonel Stewart Murray Fullarton of Bartonholm, a second cousin, married Rosetta, said to be the daughter of the Colonel Fullarton, and their two sons continued the line, however the estate had been sold in 1805 to the Duke of Portland.[3]

Free-traders

Colonel Fullarton's father, also William, died in 1759 when he was only five years old. The absence of an active laird may have encouraged the smugglers or free-traders; certainly Customs officials in Ayr at the time noted that Revenue officers could not rent property in the area because Mrs Fullarton could make much more money letting to smugglers.[24] Some of these houses may have been "brandy pots", safe houses with basements dug out to store contraband.[25]

Views of the Fullarton grotto and stables

The old Fullarton grotto.

The old Fullarton grotto. Alcoves in the old grotto.

Alcoves in the old grotto. The courtyard of Fullarton stables.

The courtyard of Fullarton stables.

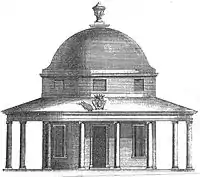

The Temple

This observatory, octagonal, with a domed roof, was located on the isthmus at Troon. This temple or pagoda had eight pillars arranged around it and was built by William Fullarton; it is marked on old maps of the area as far back as Roy's map of circa 1747. Colonel Fullarton may have altered it at some point as it was said to have some Indian design characteristics and he spent some years there in his army days. It had an inscription on it : Baccho laetitiae datori, amacis et otio sacrum, which translates as Erected to Bacchus, the giver of happiness, for friends and for leisure.[17] The Templehill area of Troon recalls this structure, also known as Fullarton's folly or the 'Temple on the Hill'. It was demolished to allow for the construction of a new harbour road.[25]

This area of the Ayrshire coast was particularly noted for smuggling activity in the eighteenth century and a story is told of a time in April 1767 when customs officials tried to obtain the use of the Temple, however Mrs Fullarton was away and the servants were 'unable or unwilling' to hand over the keys.[24]

Coal mines

Colonel Fullarton owned the estate of Bartonholm, which had various mine workings, steam pumping engines and early plateways. The workings were inundated when the coal workings broke through the bed of the River Garnock in 1833.[26] The surface of the Garnock was seen to be ruffled and it was discovered that a section of the river bed had collapsed into mineworkings beneath. The river was now flowing into miles of mineworkings of the Bartonholm, Snodgrass, and Longford collieries.

Attempts were made to block the breach with clay, whin, straw, etc. with no success. The miners had been safely brought to the surface and were able to witness the sight of the river standing dry for nearly a mile downstream, with fish jumping about in all directions. The tide brought in sufficient water to complete the flooding of the workings and the river level returned to normal. The weight of the floodwater was so great that the compressed air broke through the ground in many places and many acres of ground were observed to bubble up like a pan of boiling water. In some places rents and cavities appeared measuring four or five feet in diameter, and from these came a roaring sound described as being like steam escaping from a safety valve. For about five hours great volumes of water and sand were thrown up into the air like fountains and the mining villages of Bartonholm, Snodgrass, Longford and Nethermains were flooded.

The thirteenth Earl of Eglinton purchased all the lands concerned in 1852 and cut a short canal at Bogend, across the loop of the river involved, bypassing the breach and once the river course had been drained and sealed off he was able to have the flooded mineworkings pumped out.[27]

Parish of Fullarton

Fullarton was a village and burgh of barony, which, due to the construction of bridges, has become part of Irvine, lying on the left bank of the River Irvine opposite the town. The Fullartons of that Ilk moved to Fullarton House.[28] Technically the village belonged to the parish of Dundonald from 1690 to 1823, however it was effectively part of the parish of Irvine during these years.[29]

See also

- Laigh Milton viaduct – the Kilmarnock and Troon railway or tramway.

References

- Notes

- List of Feudal Baronies Retrieved : 2011-02-18

- Love, Page 229

- Millar, Page 80

- Troon History Archived 2009-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Close, Page 89

- Roy's Map

- Macintosh, Page 229

- Mason, Page 51

- Strawhorn, Page 30

- Love(2003), Page 225.

- McClure, Page 168

- The Crosby name

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. – II – Kyle. Edinburgh: J. Stillie. p. 422

- Site Record for Dalmilling Details

- Strawhorn, Page 43

- Mackintosh, Page 77

- McClure, Page 166

- Fullarton estate

- Strawhorn, Page 13

- History of Fullarton

- McClure, Page 69

- Dougall, Page 230.

- The Burns Encyclopedia

- McClure, Page 66

- More Troon History Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Brotchie, Page 11

- Macdonald, Page 24

- Gazetteer for Scotland

- Gazetteer for Scotland

- Sources

- Blair, Anna (1983). Tales of Ayrshire. London : Shepeard – Walwyn. ISBN 0-85683-068-2.

- Brotchie, Alan w. (2006). Some Early Ayrshire Railways. Sou'West Journal. G&SWR Association. 2006 – 7. No. 38.

- Close, Robert (1992), Ayrshire and Arran: An Illustrated Architectural Guide. Pub. Roy Inc Arch Scot. ISBN 1-873190-06-9.

- Dougall, Charles S. (1911). The Burns Country. London: A & C Black.

- Love, Dane (2003), Ayrshire: Discovering a County. Ayr: Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- MacDonald, A. M. (1968) Some notes on a Kilwinning mining disaster. Inquirer. Vol. 1, No. 3.

- Macintosh, John (1894). Ayrshire Nights' Entertainments. Kilmarnock : Dunlop and Drennan.

- Mackintosh, Ian M. (1969), Old Troon and District. Kilmarnock : George Outram.

- McClure, David (2002). Ayrshire in the Age of Improvement. Ayrshire Monographs 27. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. ISBN 0-9542253-0-9.

- Main, Gordon W. (2013). The Castles of Glasgow and the Clyde. Musselburgh : Goblinshead. ISBN 978-1-899874-59-0.

- Millar, A. H. (1885). The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire. Glasgow : Grimsay Press. ISBN 1-84530-019-X.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. – II – Kyle. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- Strawhorn, John (1985). The History of Irvine. Edinburgh : John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-140-1.

- Strawhorn John. The History of Prestwick (1994 – ed.). John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-405-2.