Cattle slaughter in India

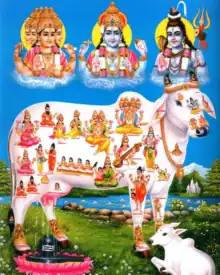

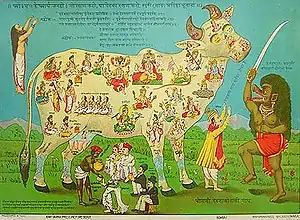

Cattle slaughter in India, especially cow slaughter, is controversial because of cattle's status as endeared and respected living beings to adherents of Dharmic religions like Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism;[2][3][4][5][6] while being an acceptable source of meat for Muslims, Christians and Jews.[7][8][9][10][11] Cow slaughter has been shunned for a number of reasons, specifically because of the cow's association with the god Krishna in Hinduism, and because cattle have been an integral part of rural livelihoods as an economic necessity.[12][13][14] Cattle slaughter has also been opposed by various Indian religions because of the ethical principle of Ahimsa (non-violence) and the belief in the unity of all life.[15][16][17][18] Legislation against cattle slaughter is in place throughout most states and territories of India.[18]

.jpg.webp)

| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

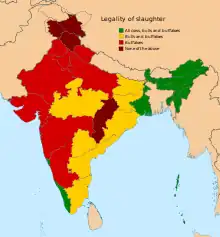

On 26 October 2005, the Supreme Court of India, in a landmark judgement, upheld the constitutional validity of anti-cow slaughter laws enacted by various state governments of India.[19][20][21][22] 20 out of 28 states in India had various laws regulating the act of slaughtered cow, prohibiting the slaughter or sale of cows.[23][24][25][26][27] Goa, Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Pondicherry, Kerala, Arunachal and the other Seven Sister States and West Bengal are the places where there are no restrictions on cow slaughter.[28][29][30][31] The ban in Kashmir was lifted in 2019.[32] As per existing meat export policy in India, the export of beef (meat of cow, oxen and calf) is prohibited.[33] Bone in meat, carcass, half carcass of buffalo is also prohibited and is not permitted to be exported. Only the boneless meats of buffalo, goat, sheep and birds are permitted for export.[34][35] India feels that the restriction on export to only boneless meat with a ban on meat with bones will add to the brand image of Indian meat. Animal carcasses are subjected to maturation for at least 24 hours before deboning. Subsequent heat processing during the bone removal operation is believed to be sufficient to kill the virus causing foot and mouth disease.[36]

The laws governing cattle slaughter in India vary greatly from state to state. The "Preservation, protection and improvement of stock and prevention of animal diseases, veterinary training and practice" is Entry 15 of the State List of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution, meaning that State legislatures have exclusive powers to legislate the prevention of slaughter and preservation of cattle. Some states permit the slaughter of cattle with restrictions like a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate which may be issued depending on factors like age and sex of cattle, continued economic viability etc. Others completely ban cattle slaughter, while there is no restriction in a few states.[37] On 26 May 2017, the Ministry of Environment of the Government of India led by Bharatiya Janata Party imposed a ban on the sale and purchase of cattle for slaughter at animal markets across India, under Prevention of Cruelty to Animals statutes,[38][39] although Supreme Court of India suspended the ban on sale of cattle in its judgement in July 2017,[40] giving relief to beef and leather industries.[41]

According to a 2016 United States Department of Agriculture review, India has rapidly grown to become the world's largest beef exporter, accounting for 20% of world's beef trade based on its large water buffalo meat processing industry.[1] Surveys of cattle slaughter operations in India have reported hygiene and ethics concerns.[42][43] According to United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization and European Union, India beef consumption per capita per year is the world's lowest amongst the countries it surveyed.[44] India produced 3.643 million metric tons of beef in 2012, of which 1.963 million metric tons was consumed domestically and 1.680 million metric tons was exported. According to a 2012 report, India ranks fifth in the world in beef production and seventh in domestic consumption.[45] The Indian government requires mandatory microbiological and other testing of exported beef.[46]

History

Indian religions

The majority of scholars explain the veneration for cattle among Hindus in economic terms, which includes the importance of dairy in the diet, use of cow dung as fuel and fertilizer, and the importance that cattle have historically played in agriculture.[47] Ancient texts such as Rig Veda, Puranas highlight the importance of the cattle.[47] The scope, extent and status of cows throughout during ancient India is a subject of debate. According to D. N. Jha's 2009 work The Myth of the Holy Cow, for example, cows and other cattle were neither inviolable nor revered in the ancient times as they were later.[48][49] Grihya sutra recommends that beef be eaten by the mourners, after a funeral ceremony, as a ritual rite of passage.[50] According to Marvin Harris, the Vedic literature is contradictory, with some suggesting ritual slaughter and meat consumption, while others suggesting a taboo on meat eating.[51]

The protection of animal life was championed by Jainism, on the grounds that violence against life forms is a source of suffering in the universe and a human being creates bad karma by violence against any living being.[52] The Chandogya Upanishad mentions the ethical value of Ahimsa, or non-violence towards all beings.[52][53] By mid 1st millennium BCE, all three major Indian religions – Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism – were championing non-violence as an ethical value, and something that affected one's rebirth. According to Harris, by about 200 CE, food and feasting on animal slaughter were widely considered as a form of violence against life forms, and became a religious and social taboo.[14][51] Ralph Fitch, a gentleman merchant of London and one of the earliest English travellers to India, wrote a letter home in 1580 stating, "They have a very strange order among them – they worship a cow and esteem much of the cow's dung to paint the walls of their houses ... They eat no flesh, but live by roots and rice and milk."[54]

The cow has been a symbol of wealth in India since ancient times.[55]

Hinduism

According to Nanditha Krishna the cow veneration in ancient India during the Vedic era, the religious texts written during this period called for non-violence towards all bipeds and quadrupeds, and often equated killing of a cow with the killing of a human being specifically a Brahmin.[56] Nanditha Krishna stated that the hymn 8.3.25 of the Hindu scripture Atharvaveda (≈1200–1500 BCE) condemns all killings of men, cattle, and horses, and prays to god Agni to punish those who kill.[57][58]

According to Harris, the literature relating to cow veneration became common in 1st millennium CE, and by about 1000 CE vegetarianism, along with a taboo against beef, became a well accepted mainstream Hindu tradition.[51] This practice was inspired by the belief in Hinduism that a soul is present in all living beings, life in all its forms is interconnected, and non-violence towards all creatures is the highest ethical value.[14][51] Vegetarianism is a part of the Hindu culture. God Krishna, one of the incarnations (Avatar) of Vishnu, is associated with cows, adding to its endearment.[14][51]

Study shows ancient Hindus ate meat-heavy food.[59] Many ancient and medieval Hindu texts debate the rationale for a voluntary stop to cow slaughter and the pursuit of vegetarianism as a part of a general abstention from violence against others and all killing of animals.[60][61] Some significant debates between pro-non-vegetarianism and pro-vegetarianism, with mention of cattle meat as food, is found in several books of the Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, particularly its Book III, XII, XIII and XIV.[60] It is also found in the Ramayana.[61] These two epics are not only literary classics, but they have also been popular religious classics.[62]

The Mahabharata debate presents one meat-producing hunter who defends his profession as dharmic.[60] The hunter, in this ancient Sanskrit text, states that meat consumption should be okay because animal sacrifice was practiced in the Vedic age, that the flesh nourishes people, that man must eat to live and plants like animals are alive too, that the nature of life is such every life form eats the other, that no profession is totally non-violent because even agriculture destroys numerous living beings when the plough digs the land.[60] The hunter's arguments are, states Alsdorf, followed by stanzas that present support for restricted meat-eating on specific occasions.[60]

The pro-vegetarianism sections of these Hindu texts counter these views. One section acknowledges that the Vedas do mention sacrifice, but not killing the animal. The proponents of vegetarianism state that Vedic teachings explicitly teach against killing, its verses can be interpreted in many ways, that the correct interpretation is of the sacrifice as the interiorized spiritual sacrifice, one where it is an "offering of truth (satya) and self-restraint (damah)", with the proper sacrifice being one "with reverence as the sacrificial meal and Veda study as the herbal juices".[63][64] The sections that appeal for vegetarianism, including abstention from cow slaughter, state that life forms exist in different levels of development, some life forms have more developed sensory organs, that non-violence towards fellow man and animals who experience pain and suffering is an appropriate ethical value. It states that one's guiding principle should be conscientious atmaupamya (literally, "to-respect-others-as-oneself").[60]

According to Ludwig Alsdorf, "Indian vegetarianism is unequivocally based on ahimsa (non-violence)" as evidenced by ancient smritis and other ancient texts of Hinduism. He adds that the endearment and respect for cattle in Hinduism is more than a commitment to vegetarianism, it has become integral to its theology.[65] According to Juli Gittinger, it is often argued that cow sacredness and protection is a fundamental quality of Hinduism, but she considers this to be a false claim.[66] This, states Gittinger, could be understood more as an example of "sanskritization" or presentation of certain traditions followed by its upper castes as purer, informed form of Hinduism and possibly an influence of Jainism on Hinduism.[66] The respect for cattle is widespread but not universal. Some Hindus (Shaktism) practice animal sacrifice and eat meat certain festivals. According to Christopher Fuller, animal sacrifices have been rare among the Hindus outside a few eastern states and Himalayan regions of the Indian subcontinent.[65][67] To the majority of modern Indians, states Alsdorf, respect for cattle and disrespect for slaughter is a part of their ethos and there is "no ahimsa without renunciation of meat consumption".[65]

Jainism

Jainism is against violence to all living beings, including cattle. According to the Jaina sutras, humans must avoid all killing and slaughter because all living beings are fond of life, they suffer, they feel pain, they like to live, and long to live. All beings should help each other live and prosper, according to Jainism, not kill and slaughter each other.[68][69]

In the Jain tradition, neither monks nor laypersons should cause others or allow others to work in a slaughterhouse.[70] Jains believe that vegetarian sources can provide adequate nutrition, without creating suffering for animals such as cattle.[70] According to some Jain scholars, slaughtering cattle increases ecological burden from human food demands since the production of meat entails intensified grain demands, and reducing cattle slaughter by 50 percent would free up enough land and ecological resources to solve all malnutrition and hunger worldwide. The Jain community leaders, states Christopher Chapple, has actively campaigned to stop all forms of animal slaughter including cattle.[71]

Jains have led a historic campaign to ban the slaughter of cows and all other animals, particularly during their annual festival of Paryushana (also called Daslakshana by the Digambara).[72] Historical records, for example, state that the Jain leaders lobbied Mughal emperors to ban slaughter of cattles and other animals, during this 8 to 12-day period. In some cases, such as during the 16th century rule of Akbar, they were granted their request and an edict was issued by Akbar. Jahangir revoked the ban upon coronation, reinstated it in 1610 when Jain community approached and appealed to him, then later reversed the 1610 ban with a new edict.[73][74]

Buddhism

The texts of Buddhism state ahimsa to be one of five ethical precepts, which requires a practicing Buddhist to "refrain from killing living beings".[75] Slaughtering cow has been a taboo, with some texts suggest taking care of a cow is a means of taking care of "all living beings". Cattle is seen as a form of reborn human beings in the endless rebirth cycles in samsara, protecting animal life and being kind to cattle and other animals is good karma.[75][76] The Buddhist texts state that killing or eating meat is wrong, and they urge Buddhist laypersons to not operate slaughterhouses, nor trade in meat.[77][78][79] Indian Buddhist texts encourage a plant-based diet.[14][51]

Saving animals from slaughter for meat, is believed in Buddhism to be a way to acquire merit for better rebirth.[76] According to Richard Gombrich, there has been a gap between Buddhist precepts and practice. Vegetarianism is admired, states Gombrich, but often it is not practiced. Nevertheless, adds Gombrich, there is a general belief among Theravada Buddhists that eating beef is worse than other meat and the ownership of cattle slaughterhouses by Buddhists is relatively rare.[80][note 1]

.

Islam

Cattle in medieval India

Hindus, like early Christians and Manichaeans,

forbade the killing and eating of meat [of cows].

—Abū Rayḥān Al-Biruni, 1017–1030 CE

Persian visitor to India[82][83]

With the arrival of Islamic rule as the Delhi Sultanate in the 12th-century, Islamic dietary practices entered India. According to the verses of the Quran, such as 16:5–8 and 23:21–23, God created cattle to benefit man and recommends Muslims to eat cattle meat, but forbids pork.[84] Cattle slaughter had been and continued to be a religiously approved practice among the Muslim rulers and the followers of Islam, particularly on festive occasions such as the Eid al-Adha.[84][85]

The earliest texts on the invasion of the Indian subcontinent mention the cow slaughter taboo, and its use by Muslim army commanders as a political message by committing the taboo inside temples.[86] For example, in the early 11th century narrative of Al-Biruni, the story of 8th-century Muhammad bin Qasim conquest of Multan is mentioned. In this Al-Biruni narrative, according to Manan Ahmed Asif – a historian of Islam in South and Southeast Asia, "Qasim first asserts the superiority of Islam over the polytheists by committing a taboo (killing a cow) and publicly soiling the idol (giving the cow meat as an offering)" before allowing the temple to continue as a place of worship.[86] In the early 13th-century Persian text of Chach Nama, the defending fort residents call the attacking Muslims in rage as "Chandalas and cow-eaters", but adds André Wink, the text is silent about "cow-worship".[87] In the texts of court historians of the Delhi Sultanate, and later the Mughal Empire, cow slaughter taboo in India is mentioned, as well as cow slaughter as a means of political message, desecration, as well as its prohibition by Sultans and Muslim Emperors as a means of accommodation of public sentiments in the Indian subcontinent.[88][89][90]

In 1756–57, in what was his fourth invasion of India, the founder of the Durrani Empire, Ahmad Shāh Durrānī sacked Delhi and plundered Agra, Mathura, and Vrindavan.[91] On his way back to Afghanistan, he attacked the Golden Temple in Amritsar and filled its sacred pool with the blood of slaughtered cows.[92]

While most Muslims consider cattle to be a source of religiously acceptable meat, some Muslim Sufi sects of India practiced vegetarianism,[93]

Christianity

European memoirs on cattle in India

They would not kill an animal on any account,

not even a fly, or a flea, or a louse,

or anything in fact that has life;

for they say these have all souls,

and it would be sin to do so.

—Marco Polo, III.20, 13th century

Venetian traveler to India[94]

Christianity is one of India's largest religions after Hinduism and Islam, with approximately 28 million followers, constituting 2.3 percent of India's population (2011 census). According to legend, the Christian faith was introduced to India by Thomas the Apostle, who supposedly reached the Malabar Coast (Kerala) in 52 AD. Later Christianity also arrived on the Indian sea coast with Christian travelers and merchants. Christians are a significant minority and a major religious group in three states of India – Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland with a plural majority in Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh and other states with significant Christian population include Coastal Andhra, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Kanara, the south shore and North-east India. Christians in India, especially the Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala, to an extent follow Hindu practices. Moreover, a significant number of Indians profess personal Christian faith outside the domain of traditional and institutionalized Christianity and do not associate with any Church or its conventional code of belief. In Christianity, no dietary restrictions exists and any kind of meat has been eaten across Christian followers in different parts of India for centuries.[95]

Mughal Empire

Cattle slaughter, in accordance with the Islamic custom, was practiced in the Mughal Empire under its Sunni rulers. Despite cow slaughter not being a crime, states Muhammad Mahbubur Rahman, "no one dared publicly to slaughter cows, particularly in Hindu-dominated areas as people could instantly punish the culprit".[96]

The Mughal emperor Humayun stopped eating beef after the killing of cows in a Hindu territory by his soldiers led to clashes, according to the Tezkerah al-Vakiat.[97] Emperor Jahangir (1605–1627), imposed a ban on cattle slaughter for a few years, not out of respect for Hindus, but because cattle had become scarce.[98]

In 1645, soon after being appointed Governor of Gujarat by Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb desecrated the Chintamani Parshvanath Jain temple near Sarashpur, Gujarat by killing a cow inside the Jain temple and lopping off the noses of the statues and converting it into a mosque calling it the "Might of Islam".[99][100][note 2] In present-day Punjab, a Hindu delegation to the 9th Sikh guru Guru Tegh Bahadur requested him to ban cow slaughter and told him "Cows are everywhere being slaughtered. If any cow or buffalo belonging to a Hindu is mortally ill, the Qazi comes and kills it on the spot. Muslims then flay it, cut it in pieces and carry it away. This causes us much distress. If we fail to inform the Qazi when a beast is dying, he punishes us, saying, 'Why did you not tell me? Now its spirit has gone to hell, whereas had it been killed in the approved Muslim manner, its spirit would have gone to paradise.'"[102] During Aurangzeb's rule, he encouraged the slaughter of cows and kept on harassing people of all religious groups other than Muslims especially the Hindus in his kingdom.

Maratha Empire

According to Ian Copland and other scholars, the Maratha Empire, which led a Hindu rebellion against the Muslim Mughal Empire and created a Hindu state in the 17th and 18th centuries, respected mosques, mausoleums and Sufi pirs.[103] However, the Maratha polity sharply enforced the Hindu sentiments for cow protection. This may be linked to the Bhakti movement that developed before the rise of the Maratha Empire, states Copland, where legends and a theology based on the compassion and love stories of Hindu god Krishna, himself a cowherd, became integral to regional religiosity.[103]

The Mahratha confederacy adopted the same approach with Portuguese Christians in the Western Ghats and the peninsular coastal regions. Marathas were liberal, state Copland and others, they respected Christian priests, allowed the building of churches and gave state land to Christian causes. However, cattle protection expected by the Hindu majority was the state norm, which Portuguese Christians were required to respect.[104]

Sikh Empire

Cow slaughter was banned by Maharajah Ranjit Singh, the founder of the Sikh Empire in Punjab. This was not due to the beliefs of Sikhs.[105] Many butcher houses were banned and restrictions were put on the slaughter of cow and sale of beef in the Sikh Empire,[106] as following the traditions, cow was as sacred to the Hindus.[107] During the Sikh reign, cow slaughter was a capital offence, for which perpetrators were even executed.[105][108]

British rule

With the advent of British rule in India, eating beef along with drinking whiskey as it was part of their food culture, in English-language colleges in Bengal, became a method of fitting in into the British culture. Some Hindus, in the 1830s, consumed beef to show how they "derided irrational Hindu customs", according to Barbara Metcalf and Thomas Metcalf.[109]

The reverence for the cow played a role in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British East India Company. Hindu and Muslim sepoys in the army of the East India Company came to believe that their paper cartridges, which held a measured amount of gunpowder, were greased with cow and pig fat as it was the best and easily accessible method available at that time for greasing weapons since cattle and pigs had a good amount of fat in them.

Historians argue that the symbol of the cow was used as a means of mobilizing Hindus.[110] In 1870, the Namdhari Sikhs started the Kuka Revolution, revolting against the British, and seeking to protect the cows from slaughter. A few years later, Swami Dayananda Saraswati called for the stoppage of cow slaughter by the British and suggested the formation of Go-samvardhani Sabhas.[111] In the 1870s, cow protection movements spread rapidly in Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Oudh State (now Awadh) and Rohilkhand. The Arya Samaj had a tremendous role in skillfully converting this sentiment into a national movement.[110]

The first Gaurakshini sabha (cow protection society) was established in the Punjab in 1882.[112] The movement spread rapidly all over North India and to Bengal, Bombay, Madras presidencies and Central Provinces. The organization rescued wandering cows and reclaimed them to groom them in places called gaushalas (cow refuges). Charitable networks developed all through North India to collect rice from individuals, pool the contributions, and re-sell them to fund the gaushalas. Signatures, up to 350,000 in some places, were collected to demand a ban on cow sacrifice.[113] Between 1880 and 1893, hundreds of gaushalas were opened.[111]

Cow protection sentiment reached its peak in 1893. Large public meetings were held in Nagpur, Haridwar and Benares to denounce beef-eaters. Melodramas were conducted to display the plight of cows, and pamphlets were distributed, to create awareness among those who sacrificed and ate them. Riots broke out between Hindus and Muslims in Mau in the Azamgarh district; it took 3 days for the government to regain control. However, Muslims had interpreted this as a promise of protection for those who wanted to perform sacrifices.[114]

The series of violent incidences also resulted in a riot in Bombay involving the working classes, and unrest occurred in places as far away as Rangoon, Burma. An estimated thirty-one to forty-five communal riots broke out over six months and a total of 107 people were killed.[113][115]

Queen Victoria mentioned the cow protection movement in a letter, dated 8 December 1893, to then Viceroy Lansdowne, writing, "The Queen greatly admired the Viceroy's speech on the Cow-killing agitation. While she quite agrees in the necessity of perfect fairness, she thinks the Muhammadans do require more protection than Hindus, and they are decidedly by far the more loyal. Though the Muhammadan's cow-killing is made the pretext for the agitation, it is, in fact, directed against us, who kill far more cows for our army, &c., than the Muhammadans."[111]

Cow slaughter was opposed by some prominent leaders of the independence movement such as Mahatma Gandhi, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Madan Mohan Malviya, Rajendra Prasad and Purushottam Das Tandon. They supported a ban on cattle slaughter once India gained its independence from the colonial British.[116]

Gandhi supported cow protection and opposed cow slaughter,[117][118] explaining the reverence for cow in March 1945.[119] Gandhi supported the leather industry, but stated that slaughter is unnecessary because the skin can be sourced from cattle after its natural death.[117]

Gandhi said, "I worship it [cow] and I shall defend its worship against the whole world," and that, "the cow is a poem of pity. One reads pity in the gentle animal. She is the mother to millions of Indian mankind. Protection of the cow means protection of the whole dumb creation of God."[117] Gandhi considered cow protection as integral to Hindu beliefs, and called "cow protection to me is one of the most wonderful phenomena in human evolution" and "cow protection is the gift of Hinduism to the world, that it is not Tilak or mantra or caste rules that judge Hindus, but "their ability to protect the cow".[117] According to Gandhi, cow protection means "protection of lives that are helpless and weak in the world". "I would not kill a human being for protection a cow", added Gandhi, and "I will not kill a cow for saving a human life, be it ever so precious".[117] On 25 July 1947, in a prayer meeting, Gandhi opposed laws that were derived from religion. He said, "In India no law can be made to ban cow-slaughter. I do not doubt that Hindus are forbidden the slaughter of cows. I have been long pledged to serve the cow but how can my religion also be the religion of the rest of the Indians? It will mean coercion against those Indians who are not Hindus."[120][121] According to Gandhi, Hindus should not demand cow slaughter laws based on their religious texts or sentiments, in the same way that Muslims should not demand laws based on Shariat (Quran, Hadith) in India or Pakistan.[121]

In 1940, one of the Special Committees of the Indian National Congress stated that slaughter of cow and its progeny must be totally prohibited. However, another Committee of the Congress opposed cow slaughter prohibition stating that the skin and leather of cow and its progeny, which is fresh by slaughter should be sold and exported to earn foreign exchange.[116]

In 1944, the British placed restrictions on cattle slaughter in India, on the grounds that the shortage of cattle was causing anxiety to the Government. The shortage itself was attributed to the increased demand for cattle for cultivation, transport, milk and other purposes. It was decided that, in respect of slaughter by the army authorities, working cattle, as well as, cattle fit for bearing offspring, should not be slaughtered. Accordingly, the slaughter of all cattle below 3 years of age, male cattle between 3 and 10 years, female cattle between 3 and 10 years of age, which are capable of producing milk, as well as all cows which are pregnant or in milk, was prohibited.[116]

During the British Raj, there were several cases of communal riots caused by the slaughter of cows. A historical survey of some major communal riots, between 1717 and 1977, revealed that out of 167 incidents of rioting between Hindus and Muslims, that although in some cases the reasons for provocation of the riots was not given, 22 cases were attributable directly to cow slaughter.[122][123]

Post-Independence

The Central Government, in a letter dated 20 December 1950, directed the State Governments not to introduce total prohibition on slaughter, stating, "Hides from slaughtered cattle are much superior to hides from the fallen cattle and fetch a higher price. In the absence of slaughter the best type of hide, which fetches good price in the export market will no longer be available. A total ban on slaughter is thus detrimental to the export trade and work against the interest of the Tanning industry in the country."[124]

In 1955, a senior Congress member of parliament Seth Govind Das drafted a bill for India's parliament for a nationwide ban on cow slaughter, stating that a "large majority of the party" was in favour. India's first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru opposed this national ban on cow slaughter, and threatened to resign if the elected representatives passed the bill in India's parliament. The bill failed by a vote of 95 to 12.[125][126] Nehru declared that it was individual states to decide their laws on cow slaughter, states Donald Smith, and criticized the ban on cow slaughter as "a wrong step".[127] However, Nehru's opposition was largely irrelevant, states Steven Wilkinson, because under India's Constitution and federal structure laws such as those on cattle slaughter has been an exclusive State subject rather than being a Central subject. State legislatures such as those of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh enacted their own laws in the 1950s.[127][128]

In 1958, a lawsuit was instigated in the Supreme Court of India regarding the constitutionality of the slaughter ban laws in the state, where Qureshi petitioned that the laws infringed on Muslim rights to freely practice their religion such as sacrificing cows on Bakr-Id day.[127] The Court determined that neither the Quran nor the Hidaya mandates cow slaughter, and the Islamic texts allow a goat or camel be sacrificed instead. Therefore, according to the Court, a total ban on cow slaughter did not infringe on the religious freedom of Muslims under Articles 25 or 48 of its Constitution.[127]

In 1966, Indian independence activist Jayaprakash Narayan wrote a letter to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi calling for a ban on cow slaughter. Narayan wrote, "For myself, I cannot understand why, in a Hindu majority country like India, where rightly or wrongly, there is such a strong feeling about cow-slaughter, there cannot be a legal ban".[124] In the same year, the Hindu organisations started an agitation demanding a ban on the slaughter of cows. But Indira Gandhi did not accede to the demand.

In July 1995, the Government of India stated before the Supreme Court that, "It is obvious that the Central Government as a whole is encouraging scientific and sustainable development of livestock resources and their efficient utilization which inter-alia includes production of quality meat for export as well as for domestic market. This is being done with a view of increasing the national wealth as well as better returns to the farmer." In recent decades, the Government has started releasing grants and loans for setting up of modern slaughter houses.[124]

Contemporary issues

Hygiene

Poor hygiene and prevalence of meat-borne disease has been reported in studies of Indian cattle slaughter-houses. For example, in a 1976–1978 survey of 1,100 slaughtered cattle in Kerala slaughter-houses, Prabhakaran and other scholars reported, "468 cases of echinococcosis and 19 cases of cysticercosis", the former affecting 365 livers and 340 lungs. The cattle liver was affected by disease in 79% of cattle and the lung in 73%.[129]

A 2001 study by Sumanth and other scholars on cattle slaughtered in Karnataka reported more than 60% of the carcasses were infected with schistosoma eggs and worms.[43] A 2007 report by Ravindran indicated over 50% of cattle slaughtered in Wayanad were infected.[42] However the population size was very limited and usually restricted to a single slaughter-house, skewing the results.

Illegal slaughterhouses and cattle theft

According to media reports, India has numerous illegal slaughterhouses. For example, in the state of Andhra Pradesh, the officials in 2013 reported over 3,000 illegal slaughterhouses.[130] Cattle are traditionally left to freely roam streets and graze in India. These are easy prey to thieves, state Rosanna Masiola and Renato Tomei.[131] According to The New York Times, the organized mafia gangs pick up the cattle they can find and sell them to these illegal slaughterhouses. These crimes are locally called "cattle rustling" or "cattle lifting".[130] In many cases, the cows belong to poor dairy farmers who lack the facility or infrastructure to feed and maintain the cows, and they don't traditionally keep them penned. According to Masiola and Tomei, the increasing meat consumption has led to cows becoming a target for theft.[132]

The theft of cattle for slaughter and beef production is economically attractive to the mafias in India. In 2013, states Gardiner Harris, a truck can fit 10 cows, each fetching about 5,000 rupees (about US$94 in 2013), or over US$900 per cattle stealing night operation. In a country where some 800 million people live on less than US$2 per day, such theft-based mafia operations are financially attractive.[130] According to Andrew Buncombe, when smuggled across its border, the price per cattle is nearly threefold higher and the crime is financially more attractive.[133] Many states have reported rising thefts of cattle and associated violence, according to The Indian Express.[134]

According to T.N. Madan, Muslim groups have been accused of stealing cattle as a part of their larger violence against non-Muslims.[135] Cattle theft, states David Gilmartin and other scholars, was a common crime in British India and has been a trigger for riots.[136][137]

According to the Bangladeshi newspaper The Daily Star, some of cattle theft operations move the cattle stolen in India across the border into Bangladesh, ahead of festivals such as Eid-ul-Azha when the demand for meat increases. The criminals dye the white or red cows into black, to make identifying the stolen cow difficult. The Border Guard Bangladesh in 2016 reported of confiscating stolen cattle, where some of cattle's original skin color had been "tampered with".[138] Hundreds of thousands of cows, states the British newspaper The Independent, are illegally smuggled from India into Bangladesh every year to be slaughtered.[133] Gangs from both sides of the border are involved in this illegal smuggling involving an estimated 1.5 million (15 lakhs) cattle a year, and cattle theft is a source of the supply, states Andrew Buncombe.[133] According to Zahoor Rather, trade in stolen cattle is one of the important crime-related border issues between India and Bangladesh.[139]

Castes and religions

Some scholars state that the Hindu views on cattle slaughter and beef eating is caste-based, while other scholars disagree. Dalit Hindus who eat beef state the former, while those who don't state that the position of Dalit Hindus on cattle slaughter is ambiguous.[140][141]

Deryck Lodrick states, for example, "beef-eating is common among low caste Hindus", and vegetarianism is an upper caste phenomenon.[140] In contrast, cow-cherishing, Krishna-worshipping rustic piety, state Susan Bayly and others, has been popular among agriculture-driven, cattle husbandry, farm laboring and merchant castes. These have typically been considered the low-castes in Hinduism.[142] According to Bayly, reverence for the cow is widely shared in India across castes. The traditional belief has also associated death or the dead with being unclean, polluting or defiling, such as those who handle corpse, carrion and animal remains.[142] However, the tradition differentiates between natural or accidental death, and intentional slaughter. According to Frederick J. Simoons, many members of low castes and tribal groups in India reject "cow slaughter and beef eating, some of them quite strongly", while others support beef eating and cattle slaughter.[11]

According to Simoons and Lodrick, the reverence for cattle among Hindus, and Indians in general, is more comprehensively understood by considering both the religious dimensions and the daily lives in rural India.[143] The veneration of cow across various Hindu castes, states Lodrick, emerged with the "fifteenth century revival of Vaishnavism", when god Krishna along with his cows became a popular object of bhakti (devotional worship).[144] In contrast, other scholars such as J. A. B. van Buitenen and Daniel Sheridan state that the theology and the most popular texts related to Krishna, such as the Bhagavad Gita was composed by about 2nd century BCE,[145] and the Bhagavata Purana was composed between 500 and 1000 CE.[146][147]

According to People's Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), some Dalits work in leather which includes cow-skin and they rely on it for their livelihood. The position of Dalits to cow-protection is highly ambivalent, states PUDR, given their Hindu identity and the "endemic contradiction – between the 'Hindu' ethos of protecting the cow and a trade dependent fundamentally on the skin of cows".[148] The selling of old cattle for skin, according to them, is supported by members of both "dominant and subordinate castes" for the leather-related economy.[149] Dominant groups, officials and even some Dalits state that "Dalits are cow-protectors". The inclusion of Dalits in cow-protection ideology, according to PUDR, is accompanied by "avowal of loyalty to cow-protection" exposing the fragility of the cow-protection ideology across castes.[150]

Some Dalit student associations in the Hyderabad region state that beef preparations, such as beef biryani, is the traditional food of low-castes. Historical evidence does not support this claim, state Claude Levy-Straus and Brigitte Sebastia. Beef as the traditional food of impoverished Dalits is a reconstruction of history and Indian beef dishes are a Mughal era innovation and more recently invented tradition. It is the nineteenth century politics that has associated beef and cattle slaughter with Muslim and Dalit identity, states Sebastia.[151]

Economic imperative

According to anthropologist Marvin Harris, the importance of cattle to Hindus and other religious groups is beyond religion, because the cattle has been and remains an important pillar of rural economy.[152] In the traditional economy, states Harris, a team of oxen is "Indian peasant's tractor, thresher and family car combined", and the cow is the factory that produces those oxen.[152][note 3] The cattle produce nutritious milk, their dung when dried serves as a major cooking fuel, and for the poor the cattle is an essential partner in many stages of agriculture. When cattle fall sick, the family worries over them like Westerners do over their pets or family members. A natural loss of a cattle from untimely death can cripple a poor family, and thus slaughtering a creature so useful and essential is unthinkable. According to Harris, India's unpredictable monsoons and famines over its history meant even greater importance of cattle, because Indian breeds of cattle can survive with little food and water for extended periods of time.[152]

According to Britha Mikkelsen and other scholars, cow dung produced by young and old cattle is the traditional cooking fuel as dung-cakes and fertilizer in India. The recycling substitutes over 25 million tons of fossil fuels or 60 million tons of wood every year, providing the majority of cooking fuel needs in rural India.[153][154] In addition to being essential fuel for rural family, cattle manure is a significant source of fertilizer in Indian agriculture.[155]

The Indian religions adapted to the rural economic constraints, states Harris. Preserving cattle by opposing slaughter has been and remains an economic necessity and an insurance for the impoverished.[152] The cow is sacred in India, states Harris, not because of superstitious, capricious and ignorant beliefs, but because of real economic imperatives and cattle's role in the Indian tradition of integrated living. Cattle became essential in India, just like dogs or cars became essential in other human cultures, states Harris.[152]

Animal cruelty

The slaughterhouses in India have been accused of cruelty against animals by PETA and other humane treatment of animals-groups.[156] According to PETA and these groups, the slaughterhouse workers slit animals' throats with dull blades and let them bleed to death. Cattle are skinned and dismembered while they are still alive and in full view of other animals.[156]

The Supreme Court of India, in February 2017, ordered a state governments to stop the illegal slaughterhouses and set up enforcement committees to monitor the treatment of animals used for meat and leather.[156] The Court has also ruled that the Indian Constitution requires Indian citizens to show compassion to the animal kingdom, respect the fundamental rights of animals, and asked the states to prevent cruelty to animals.[157]

Vigilantism

According to Judith Walsh, widespread cow protection riots occurred repeatedly in British India in the 1880s and 1890s. These were observed in regions of Punjab, United Provinces, Bihar, Bengal, Bombay Presidency and in parts of South Burma (Rangoon). The anti-Cow Killing riots of 1893 in Punjab caused the death of at least 100 people.[158][159] The 1893 cow killing riots started during the Muslim festival of Bakr-Id, the riot repeated in 1894, and they were the largest riots in British India after the 1857 revolt.[160] One of the issues, states Walsh, in these riots was "the Muslim slaughter of cows for meat, particularly as part of religious festivals such as Bakr-Id".[159]

According to Mark Doyle, the first cow protection societies on the Indian subcontinent were started by Kukas of Sikhism (also called Namdharis).[161] The Sikh Kukas or Namdharis were agitating for cow protection after the British annexed Punjab. In 1871, states Peter van der Veer, Sikhs killed Muslim butchers of cows in Amritsar and Ludhiana, and viewed cow protection as a "sign of the moral quality of the state".[162] According to Barbara Metcalf and Thomas Metcalf, Sikhs were agitating for the well-being of cows in the 1860s, and their ideas spread to Hindu reform movements.[163] Cattle protection-related violence continued at numerous occasions, often over the Muslim festival of Bakri-Id, in the first half of the 20th century.[164][165]

Cow slaughter in contemporary India has triggered riots and violent vigilante groups.[158][166][167]

According to PUDR, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a Hindu group, and the Gauraksha Samiti have defended violent vigilantism around cow protection as sentiments against the "sin of cow-slaughter" and not related to "the social identity of the victims".[168] Various groups, such as the families of Dalits who were victims of a mob violence linked to cow-slaughter in 2002, did not question the legitimacy of cow protection.[169]

According to a Reuters report, citing IndiaSpend analysis, a total of "44 Indians – 39 of them Muslims – have been killed and 124 injured", between 2010 and June 2018 in cow-related violence.[170]

Stray cattle

Fear of arrest, persecution, and of lynching by cow vigilantes has reduced the trading of cattle. Once a cow stops giving milk, feeding and maintenance of the cow becomes a financial burden on the farmer who cannot afford their upkeep. Cattle that farmers are unable to sell are eventually abandoned.

India has over 5 million stray cattle according to the livestock census data released in January 2020.[171] The stray cow attacks on humans and crops in both urban and rural areas is an issue for the residents.[172][173] Stray cattle are a nuisance to traffic in urban areas and frequently cause road accidents.[171][174] The problem of solid waste pollution, especially plastic pollution and garbage dumped at public places, poses a risk to stray cattle which feed on garbage.[175]

Legislation

The "Preservation, protection and improvement of stock and prevention of animal diseases, veterinary training and practice" is Entry 15 of the State List of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution, meaning that State Legislatures have exclusive powers to legislate the prevention of slaughter and preservation of cattle.[176][177]

The prohibition of cow slaughter is also one of the Directive Principles of State Policy contained in Article 48 of the Constitution. It reads, "The State shall endeavour to organise agriculture and animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines and shall, in particular, take steps for preserving and improving the breeds, and prohibiting the slaughter of cows and calves and other milch and draught cattle."[178]

Several State Governments and Union Territories (UTs) have enacted cattle preservation laws in one form or the other. Arunachal Pradesh, Kerala, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, Lakshadweep, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands have no legislation. All other states/UTs have enacted legislation to prevent the slaughter of cow and its progeny.[179] Kerala is a major consumer of beef and has no regulation on the slaughter of cow and its progeny. As a result, cattle is regularly smuggled into Kerala from the neighbouring States of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, for the purpose of slaughter.[179] There have been several attacks on cow transporters, on the suspicion of carrying cows for slaughter.[180][181][182][183] Between May 2015 and May 2017, at least ten Muslims were killed in these attacks.[181]

In 1958, Muslims of Bihar petitioned the Supreme Court of India that the ban on cow slaughter violated their religious right. The Court unanimously rejected their claim.[184]

In several cases, such as Mohd. Hanif Qureshi v. State of Bihar (AIR 1959 SCR 629), Hashumatullah v. State of Madhya Pradesh, Abdul Hakim and others v. State of Bihar (AIR 1961 SC 448) and Mohd. Faruk v. State of Madhya Pradesh, the Supreme Court has held that, "A total ban [on cattle slaughter] was not permissible if, under economic conditions, keeping useless bull or bullock be a burden on the society and therefore not in the public interest."[85] The clause "under economic conditions, keeping useless (...)" has been studied by the Animal Welfare Board of India which determined that the fuel made from cow dung for household cooking purposes in the Indian society suggests that the cattle is never useless while it produces dung.[85]

In May 2016, Bombay High Court gave the judgement that consumption or possession of beef is legal under Article 21 of Constitution of India, but upheld the ban on cow slaughter in the state of Maharashtra.[185][186]

The Supreme Court of India heard a case between 2004 and 2017. The case petitioned the Court to order a ban on the common illegal treatment of animals during transport and slaughter. In February 2017, the Court ordered a state governments to stop the illegal slaughterhouses and set up enforcement committees to monitor the treatment of animals used for meat and leather.[156] The Court has also ruled, according to a Times of India report, that "it was evident from the combined reading of Articles 48 and 51- A(g) of the [Indian] Constitution that citizens must show compassion to the animal kingdom. The animals have their own fundamental rights. Article 48 specifically lays down that the state shall endeavour to prohibit the slaughter of cows and calves, other milch and draught cattle".[157]

Non-uniformity

No state law explicitly bans the consumption of beef. There is a lack of uniformity among State laws governing cattle slaughter. The strictest laws are in Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand, where the slaughter of cow and its progeny, including bulls and bullocks of all ages, is completely banned. However, in Uttarakhand, slaughter of cows and bulls which are deemed to be injured or otherwise useless, is permitted with necessary permission. Most States prohibit the slaughter of cows of all ages. However, Assam and West Bengal permit the slaughter of cows of over the ages of 10 and 14 years, respectively. Most States prohibit the slaughter of calves, whether male or female. With the exception of Bihar and Rajasthan, where age of a calf is given as below 3 years, the other States have not defined the age of a calf. According to the National Commission on Cattle, the definition of a calf being followed in Maharashtra, by some executive instructions, was "below the age of 1 year".[187][188]

In Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, Delhi, Goa, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Puducherry, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand violation of State laws on cattle slaughter are both cognizable and non-bailable offences. Most of other states specify that offences would be cognizable only. The maximum term of imprisonment varies from 6 months to 14 years(life-term) and the fine from ₹1,000 to ₹5,00,000. Delhi and Madhya Pradesh have fixed a mandatory minimum term of imprisonment at 6 months.

Cows are routinely shipped to states with lower or no requirement for slaughter, even though it is illegal in most states to ship animals across state borders to be slaughtered.[189][190] Many illegal slaughterhouses operate in large cities such as Chennai and Mumbai. As of 2004, there were 3,600 legal and 30,000 illegal slaughterhouses in India.[191] Efforts to close them down have, so far, been largely unsuccessful. In 2013, Andhra Pradesh estimated that there were 3,100 illegal and 6 licensed slaughterhouses in the State.[192]

Constituent Assembly

After India attained Independence, the members of the Constituent Assembly, a body consisting of indirectly elected representatives set up for the purpose of drafting a constitution for India, debated the question of making a provision for the protection and preservation of the cow in the Constitution of India. An amendment for including a provision in the Directive Principles of State Policy as Article 38A was introduced by Pandit Thakur Dass Bhargava. The amendment read, "The State shall endeavour to organise agriculture and animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines and shall in particular take steps for preserving and improving the breeds of cattle and prohibit the slaughter of cow and other useful cattle, specially milch and draught cattle and their young stock".[193]

Another amendment motion was moved by Seth Govind Das, who sought to extend the scope of the provisions for prohibiting slaughter to cover cow and its progeny by adding the following words at the end of Bhargava's amendment, "'The word "cow' includes bulls, bullocks, young stock of genus cow". Bhargava's amendment was passed by the Constituent Assembly, but Das' was rejected.[193]

Pandit Thakur Dass Bhargava (East Punjab), Seth Govind Das (Central Provinces and Berar), Shibban Lal Saksena (United Provinces), Ram Sahai (United State of Gwalior-Indore-Malwa: Madhya Bharat), Raghu Vira (Central Provinces and Berar) and Raghunath Vinayak Dhulekar (United Provinces) strongly pleaded for the inclusion of a provision in the Constitution for prohibiting the slaughter of cows. Although some members were keen on including the provision in the chapter on Fundamental Rights but, later as a compromise and on the basis of an assurance given by B. R. Ambedkar, the amendment was moved for inclusion as a Directive Principle of State Policy.[193]

Bhargava stated that "While moving this amendment, I have hesitation in stating that for people like me and those that do not agree with the point of view of Ambedkar and others, this entails, in a way, a sort of sacrifice. Seth Govind Das had sent one such amendment to be included in the Fundamental Rights and other members also had sent similar amendments. To my mind, it would have been much better if this could have been incorporated in the Fundamental Rights, but some of my Assembly friends differed and it is the desire of Ambedkar that this matter, instead of being included in Fundamental Rights should be incorporated in the Directive Principles. As a matter of fact, it is the agreed opinion of the Assembly that this problem should be solved in such a manner that the objective is gained without using any sort of coercion. I have purposely adopted this course, as to my mind, the amendment fulfills our object and is midway between the Directive Principles and the Fundamental Rights." Bhargava also observed that "I do not want that, due to its inclusion in the Fundamental Rights, non-Hindus should complain that they have been forced to accept a certain thing against their will." The result of the debate in the Constituent Assembly was that the Bhargava's amendment was carried and the Article in its present form exists as Article 48 of the Constitution, as one of the Directive Principles of State Policy.[193]

Parliament

A number of Private Member's Bills and Resolutions regarding the prevention of cow slaughter have been introduced in both Houses of Parliament, from time to time. However, none have been successful in obtaining a complete nationwide ban on cow slaughter. Attempts to address the issue through a central legislation or otherwise are described below.[194]

Vinoba Bhave went on an indefinite fast from 22 April 1979 demanding that the Governments of West Bengal and Kerala agree to enact legislation banning cow slaughter. On 12 April 1979, a Private Members Resolution was passed in the Lok Sabha, by 42 votes to 8, with 12 absentees. It read, "This House directs the Government to ensure total ban on the slaughter of cows of all ages and calves in consonance with the Directive Principles laid down in Article 48 of the Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme Court, as well as necessitated by strong economic considerations based on the recommendations of the Cattle Preservation and Development Committee and the reported fast by Acharya Vinoba Bhave from 21st April, 1979".[195]

Then Prime Minister Morarji Desai later announced in Parliament that the government would initiate action for amending the Constitution with a view to conferring legislative competence on the Union Parliament for legislating on the subject of cow protection. Accordingly, a Constitution Amendment Bill seeking to bring the subject of prevention of cow slaughter on to the Concurrent List was introduced in the Lok Sabha on 18 May 1979. The Bill, however, lapsed on account of dissolution of the Sixth Lok Sabha. Bhave reiterated his demand for a total ban on cow slaughter in July 1980, while addressing the All India Goseva Sammelan. He also requested that cows should not be taken from one State to another.[195]

In 1981, the question of amending the Constitution by introducing a Bill was again examined by the Government, but, in view of the sensitive nature of the issue and owing to political compulsions a "wait and watch" policy was adopted. A number of complaints were received from time to time that despite the ban on the slaughter of cow and its progeny, healthy bullocks were being slaughtered under one pretext or the other and calves were being maimed, so that they could be declared useless and ultimately slaughtered.[195]

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, in her letter dated 24 February 1982 wrote to the Chief Ministers of 14 States viz. Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Jammu and Kashmir, in which she desired that the ban be enforced in letter and spirit, that the ban on cow slaughter is not allowed to be circumvented by devious methods, and that Committees to inspect cattle before they are admitted to slaughter houses be adopted.[195]

Recognizing that the problem basically arose on account of inaction or obstruction on the part of a few States and large scale smuggling of cows and calves from a prohibition State to a non-prohibition State like Kerala was taking place, a suggestion was made that this problem be brought to the notice of the Sarkaria Commission, which was making recommendations regarding Centre-State relations, but this idea was dropped as the commission was then in the final stages of report-writing.[195]

Legislation by State or Union Territory

The legal status of cattle slaughter in Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshadweep is unknown.

Andhra Pradesh

The Andhra Pradesh Prohibition of Cow Slaughter and Animal Preservation Act, 1977 governs the slaughter of cattle (cows and buffaloes) in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Therefore, the law governing the slaughter of cattle in Andhra Pradesh is the same as that in Telangana.

In the case of cows, the law makes a distinction between males and females. The slaughter of female cows and of heifers is totally forbidden. The slaughter of bulls and bullocks is permitted upon obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate, to be issued only if the animal is "not economical or is not likely to become economical for the purpose of breeding or draught/agricultural operations." The certificate can be issued by any veterinary doctor and is a source of much corruption and misuse. The law also prohibits the slaughter of calves, whether male or female. The age limit of "calf" is not defined.

In the case of buffaloes, the law firstly forbids in absolute terms the slaughter of calves, whether male or female. Again, the age limit of "calf" is not defined and therefore there is much misuse, resulting in the slaughter of many young male animals who are only a few months old. Secondly, the law forbids the slaughter of adult buffaloes unless a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate is issued by a veterinarian. The certificate can be issued if the animal is deemed "uneconomical for purposes of milking, breeding or draught/agricultural operations." Thus, the law permits the slaughter of all adult male buffaloes and of all old and "spent" female buffaloes whose milk yield is not economical. For this reason, the slaughter of buffaloes, both male and female, is rampant in Andhra Pradesh.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of 6 months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

Arunachal Pradesh

No ban on cattle slaughter.[197]

Assam

The Assam Cattle Preservation Act, 1950 governs the slaughter of cattle in Assam.

Slaughter of all cattle, including bulls, bullocks, cows, calves, male and female buffaloes and buffalo calves is prohibited. Slaughter of cattle is permitted on obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate, to be given if cattle is over 15 years of age or has become permanently incapacitated for work or breeding due to injury, deformity or any incurable disease.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of 6 months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

In 2021 Assam Assembly passed a bill that prohibits the slaughter or sale of beef within a 5-km radius of any temple. The legislation seeks to ensure that permission for slaughter is not granted to areas that are predominantly inhabited by Hindu, Jain, Sikh and other non-beef eating communities or places that fall within a 5-km radius of a temple, satra and any other institution as may be prescribed by the authorities. Exemptions, however, might be granted for certain religious occasions.[198][199]

Bihar

The Bihar Preservation and Improvement of Animals Act, 1955 governs the slaughter of cattle in Bihar.

Slaughter of cow and calf is totally prohibited. Slaughter of bulls or bullocks of over 25 years of age or permanently incapacitated for work or breeding due to injury, deformity or any incurable disease is permitted. The law also bans the export of cows, calves, bulls and bullocks from Bihar, for any purpose. The law defines a bull as "an uncastrated male of above 3 years", a bullock as "castrated male of above 3 years", a calf as "male or female below 3 years" and a cow as "female above 3 years".

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of 6 months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

Chandigarh

The Punjab Prohibition of Cow Slaughter Act, 1955 applies to Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. Therefore, the law governing the slaughter of cattle in Chandigarh has the same provisions as that in Himachal Pradesh and Punjab.

Slaughter of cow (includes bull, bullock, ox, heifer or calf), and its progeny, is totally illegal. The export of cattle for slaughter and the sale of beef are both illegal.[196] This "does not include flesh of cow contained in sealed containers and imported", meaning that restaurants in the states can serve beef, if they can prove its meat has been imported into the state. The law also excuses the killing of cows "by accident or in self defence".[200] Consumption is not penalized.[197] Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196]

Chhattisgarh

"Chhattisgarh Agricultural Cattle Preservation Act, 2004" applies to the state. The operative sections of the Act prohibit slaughter of all agricultural cattle; possession of the beef of any agricultural cattle; and, transport of agricultural cattle ‘for the purpose of its slaughter… or with the knowledge that it will be or is likely to be, so slaughtered’. The Schedule lists Agricultural Cattle as: 1. Cows of all ages. 2. Calves of cows and of she buffaloes. 3. Bulls. 4. Bullocks. 5. Male and Female buffaloes.[201]

Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu

The Goa, Daman & Diu Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act, 1978 governs the slaughter of cattle in Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu.

Under the 1978 Act, which also applies to Goa, there is a total ban on slaughter of cow (includes cow, heifer or calf), except when the cow is suffering pain or contagious disease or for medical research. The law does not define the age of a "calf". There is also a total prohibition on the sale of beef or beef products in any form in the union territory.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196]

Delhi

The Delhi Agricultural Cattle Preservation Act, 1994 governs the slaughter of cattle in Delhi.

Slaughter of all agricultural cattle is totally prohibited. The law defines "agricultural cattle" as cows of all ages, calves of cows of all ages, and bulls and bullocks.[196] The slaughter of buffaloes is legal. The possession of the flesh of agricultural cattle slaughtered outside Delhi is also prohibited.[200] The transport or export of cattle for slaughter is also prohibited. Export for other purposes is permitted on declaration that cattle will not be slaughtered. However, export to a state where slaughter is not banned by law is not permitted.[196]

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to 5 years and fine up to ₹ 10,000, provided that minimum imprisonment should not be for less than 6 months and fine not less than ₹ 1,000. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196]

Goa

The Goa, Daman & Diu Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act, 1978 and The Goa Animal Preservation Act, 1995 govern the slaughter of cattle in Goa.

Under the 1978 Act, which also applies to Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu, there is a total ban on slaughter of cow (includes cow, heifer or calf), except when the cow is suffering pain or contagious disease or for medical research. The law does not define the age of a "calf".

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.This act though, has not been necessarily implemented.[202]

The Goa Animal Preservation Act, 1995 applies to bulls, bullocks, male calves and buffaloes of all ages. All the animals can be slaughtered on obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate which is not given if the animal is likely to become economical for draught, breeding or milk (in the case of she-buffaloes) purposes. The sale of beef obtained in contravention of the above provisions is prohibited. However, sale of beef imported from other states is legal.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of 6 months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

Gujarat

The Bombay Animal Preservation Act, 1954 governs the slaughter of cattle in Gujarat.

Slaughter of cows, calves of cows, bulls and bullocks is totally prohibited. Slaughter of buffaloes is permitted on certain conditions.

Anyone violating the law could be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of 6 months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

The Gujarat Animal Preservation (Amendment) Act, 2011 was passed unopposed in the Gujarat Legislative Assembly, with support from the main opposition party, on 27 September 2011. The amendment, which came into effect in October 2011, criminalized transporting the animal for the purpose of slaughter and included a provision to confiscate the vehicle used for carrying cow meat. It also increased the maximum jail term for slaughtering cattle to 7 years and maximum fine to ₹ 50,000.[203][204][205]

In 2017, the Gujarat Assembly amended the bill further extending the punishment and fine. The punishment was increased to a minimum of 10 years and a maximum of 'life term of a 14 years', and the fine was enhanced to the range of ₹1 lakh – ₹5 lakh. The new law also made offences under the amended Act non-bailable.[206][207][208][209]

Haryana

Haryana Gauvansh Sanrakshan and Gausamvardhan Act, 2015 applies to Haryana.[210]

Earlier, "The Punjab Prohibition of Cow Slaughter Act, 1955" was the law governing the slaughter of cattle in Haryana has the same provisions as that in Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. However, Haryana has stricter penalties for violating the law than the other two states and Chandigarh, even prior to 2015 Act.

Slaughter of cow (includes bull, bullock, ox, heifer or calf), and its progeny, is "totally prohibited". The export of cattle for slaughter and the sale of beef are both prohibited.[196] This "does not include flesh of cow contained in sealed containers and imported", meaning that restaurants in the states can serve beef, if they can prove its meat has been imported into the state. The law also excuses the killing of cows "by accident or in self defence".[200] Consumption of beef is not penalized.[197]

Anyone violating the law can be punished with rigorous imprisonment up to 10 years or fine up to ₹1 lakh or both. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196][210]

Himachal Pradesh

The Punjab Prohibition of Cow Slaughter Act, 1955 applies to Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. Therefore, the law governing the slaughter of cattle in Himachal Pradesh is the same as that in Chandigarh and Punjab.

Slaughter of cow (includes bull, bullock, ox, heifer or calf), and its progeny, is totally prohibited. The export of cattle for slaughter and the sale of beef are both prohibited.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196]

Jammu and Kashmir

The Ranbir Penal Code, 1932 governed the slaughter of cattle in Jammu and Kashmir which is now repealed.

Voluntary slaughter of any bovine animal such as ox, bull, cow or calf shall be punished with imprisonment of either description which may extend to 10 years and shall also be liable to fine. The fine may extend to 5 times the price of the animals slaughtered as determined by the court. Possession of the flesh of slaughtered animals is also an offence punishable with imprisonment up to 1 year and fine up to ₹ 500.[196]

In 2019, the 150 year old ban on cow slaughter was lifted, an unexpected result of the end of the special status of Kashmir and Ladakh. The move to re-criminalise beef consumption and sale on the grounds of environmental activism in India, was overturned by the High Court of Kashmir.[211][32][212][213]

Jharkhand

The Bihar Preservation and Improvement of Animals Act, 1955 governs the slaughter of cattle in Jharkhand.

Slaughter of cow and calf is totally prohibited. Slaughter of bulls or bullocks of over 15 years of age or permanently incapacitated for work or breeding due to injury, deformity or any incurable disease is permitted. The law also bans the export of cows, calves, bulls and bullocks from Jharkhand for any purpose. The law defines a bull as "an uncastrated male of above 3 years", a bullock as "castrated male of above 3 years", a calf as "male or female below 3 years" and a cow as "female above 3 years".

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of 6 months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

Karnataka

The Karnataka Prevention of Cow Slaughter and Cattle Preservation Act, 1964 governed the slaughter of cattle in Karnataka until 2020 and was replaced by The Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Act, 2020.[214] In 2010, the Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Act, 2010 and in 2014, the Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Act (Amendment), 2014 were introduced by subsequently withdrawn.[214]

Up to 2020, the slaughter of cow, calf of a cow (male or female) or calf of a she-buffalo totally prohibited. Slaughter of bulls, bullocks and adult buffaloes was permitted on obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate provided cattle is over 12 years of age or is permanently incapacitated for breeding, draught or milk due to injury, deformity or any other cause. Transport for slaughter to a place outside the state not permitted. Sale, purchase or disposal of a cow or a calf, for slaughter, is not permitted.

Up to 2020 anyone violating the law could be punished with imprisonment up to maximum of six months or fine of up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

In January 2021, the Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Act, 2020 became official. This act applied to any breed of cattle up to twelve years of age.[215]

With the act, people found guilty of breaking the law would receive a prison sentence of 3 to 7 years. People found guilty would also receive a monetary fine between 50,000 rupees to 10 lakh depending on the number of times of breaking this law.[216]

Only Buffaloes thirteen years and older are exempted from this law. Buffaloes that can not produce milk or reproduce are also exempted.[217]

Kerala

Kerala permits the slaughter of every type of cattle. Slaughtering of animals is formally regulated by the government in order to maintain public health and sanitation. Panchayat laws permit slaughter only in approved slaughter houses.[218] Beef accounts for 25% of all meat consumed in Kerala.[219] Beef is sold at meat shops while cattle is traded at weekly markets across the state.[220] Further, it has been ruled an obligation of panchayat to provide for meat stalls, including those that may sell beef.[221]

Ladakh

The Ranbir Penal Code, 1932 governed the slaughter of cattle in Ladakh which is now repealed and has not been replaced by any new law.

Voluntary slaughter of any bovine animal such as ox, bull, cow or calf shall be punished with imprisonment of either description which may extend to 10 years and shall also be liable to fine. The fine may extend to 5 times the price of the animals slaughtered as determined by the court. Possession of the flesh of slaughtered animals is also an offence punishable with imprisonment up to 1 year and fine up to ₹ 500.[196]

Madhya Pradesh

The Madhya Pradesh Agricultural Cattle Preservation Act, 1959 governs the slaughter of cattle in Madhya Pradesh.

Slaughter of cows, calves of cows, bulls, bullocks and buffalo calves is prohibited. However, bulls and bullocks are being slaughtered in the light of a Supreme Court judgement, provided the cattle is over 20[222] years or has become unfit for work or breeding. Transport or export of cattle for slaughter not permitted. Export for any purpose to another State where cow slaughter is not banned by law is not permitted. The sale, purchase and/or disposal of cow and its progeny and possession of flesh of cattle is prohibited.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 3 years and fine of ₹ 5,000 or both. Normally imprisonment shall not be less than 6 months and fine not less than ₹ 1,000. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

Maharashtra

The Maharashtra Animal Preservation Act, 1976 governs the slaughter of cattle in Maharashtra.

Slaughter of cows (includes a heifer or male or female calf of a cow) is totally prohibited.[223] Slaughter of bulls, bullocks and buffaloes is allowed on obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter certificate", if it is not likely to become economical for draught, breeding or milk (in the case of she-buffaloes) purposes.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 6 months and a fine of up to ₹ 1,000. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196] Maharashtra cow slaughter ban was later extended to ban the sale and export of beef, with a punishment of 5 years jail, and/or a ₹ 10,000 fine for possession or sale.[224][225] This law came into effect from 2 March 2015.[226]

Manipur

In Manipur, cattle slaughter is restricted under a proclamation by the Maharaja in the Durbar Resolution of 1939. The proclamation states, "According to Hindu religion the killing of cow is a sinful act. It is also against Manipuri Custom."[196] However, beef is largely consumed in the hill districts with large Christian populations and sold openly in cities like Churachandpur.[220]

Meghalaya

No ban on cattle slaughter, beef consumed widely.[196]

Mizoram

No ban on cattle slaughter, beef consumed widely.[197]

Nagaland

No ban on cattle slaughter, beef consumed widely.[196]

Odisha

The Orissa Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act, 1960 governs the slaughter of cattle in Odisha.

Slaughter of cows (includes heifer or calf) is totally prohibited. Slaughter of bulls and bullocks is permitted, on obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate, provided that the cattle is over 14 years of age or has become permanently unfit for breeding or draught.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable offence.[196]

Puducherry

The Pondicherry Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act, 1968 governs the slaughter of cattle in Puducherry.

Slaughter of cows (includes heifer or calf) is totally prohibited. Slaughter of bulls and bullocks is permitted, on obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate, provided that the cattle is over age of 15 years or has become permanently unfit for breeding or draught. The sale and/or transport of beef is prohibited.

Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196]

Punjab

The Punjab Prohibition of Cow Slaughter Act, 1955 applies to Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh and Punjab. Therefore, the law governing the slaughter of cattle in Punjab has the same provisions as that in Chandigarh and Himachal Pradesh.

Slaughter of cow (includes bull, bullock, ox, heifer or calf), and its progeny, is totally illegal. The export of cattle for slaughter and the sale of beef are both illegal.[196] This "does not include flesh of cow contained in sealed containers and imported", meaning that restaurants in the states can serve beef, if they can prove its meat has been imported into the state. The law also excuses the killing of cows "by accident or in self defense".[200] Consumption is not penalized.[197] Anyone violating the law can be punished with imprisonment up to a maximum of 2 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both. The law places the burden of proof on the accused. The crime is treated as a cognizable and non-bailable offence.[196]

Rajasthan

The Rajasthan Bovine Animal (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 1995 governs the slaughter of cattle in Rajasthan.

Slaughter of all bovine animals (includes cow, calf, heifer, bull or bullocks) is prohibited. Possession, sale and/or transport of beef and beef products is prohibited. The export of bovine animals for slaughter is prohibited. The law requires custody of seized animals to be given to any recognized voluntary animal welfare agency failing which to any Goshala, Gosadan or a suitable person who volunteers to maintain the animal. Government of Rajasthan has also introduced a Bill (Bill No. 16/2015) to ban migration out of State and slaughter of Camels in the State.[227]

Anyone violating the law can be punished with rigorous imprisonment of not less than 1 year and up to a maximum of 2 years and fine up to ₹ 10,000. The law places the burden of proof on the accused.[196]

Sikkim

Under The Sikkim Prevention of Cow Slaughter Act, 2017, cow slaughter is a non-bailable offence in Sikkim.[197]

Tamil Nadu

The Tamil Nadu Animal Preservation Act, 1958 governs the slaughter of cattle in Tamil Nadu.

All animals may be slaughtered upon obtaining a "fit-for-slaughter" certificate. The law defines "animals" as bulls, bullocks, cows, calves; and buffaloes of all ages. The certificate is issued when an animal is over 10 years of age, unfit for labor, breeding or had become permanently incapacitated for work and breeding due to injury deformity or any incurable disease.

Anyone violating the Act can be punished with imprisonment of up to 3 years or fine up to ₹ 1,000 or both.[196]

Telangana