Moonrise Kingdom

Moonrise Kingdom is a 2012 American coming-of-age comedy-drama film directed by Wes Anderson, written by Anderson and Roman Coppola, and starring Bruce Willis, Edward Norton, Bill Murray, Frances McDormand, Tilda Swinton, Jason Schwartzman, Bob Balaban, and introducing Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward. Largely set on the fictional island of New Penzance somewhere off the coast of New England, it tells the story of an orphan boy (Gilman) who escapes from a scouting camp to unite with his pen pal and love interest, a girl with aggressive tendencies (Hayward). Feeling alienated from their guardians and shunned by their peers, the lovers abscond to an isolated beach. Meanwhile, the island's police captain (Willis) organizes a search party of scouts and family members to locate the runaways.

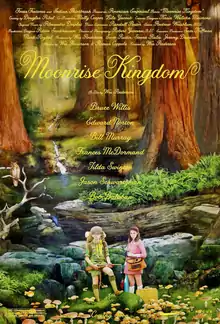

| Moonrise Kingdom | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Wes Anderson |

| Written by | Wes Anderson Roman Coppola |

| Produced by | Wes Anderson Scott Rudin Steven Rales Jeremy Dawson |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Yeoman |

| Edited by | Andrew Weisblum |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Focus Features |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 94 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $16 million |

| Box office | $68.3 million |

In crafting their screenplay, Anderson and Coppola drew from personal experiences and memories of childhood fantasies as well as films including Melody (1971) and The 400 Blows (1959). Auditions for child actors took eight months, and filming took place in Rhode Island over three months in 2011.

Moonrise Kingdom premiered at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival and received critical acclaim, with its themes of young love, child sexuality, juvenile mental health, and the Genesis flood narrative being praised. Critics cited the film's color palette and use of visual symmetry as well as the use of original composition by Alexandre Desplat to supplement existing music by Benjamin Britten. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and the Golden Globe for Best Musical or Comedy. In 2016, the BBC included the film in its list of greatest films of the twenty-first century.

Plot

On the New England island of New Penzance, 12-year-old orphan Sam Shakusky attends Camp Ivanhoe, a Khaki Scout summer camp led by Scout Master Randy Ward. Suzy Bishop, also 12, lives on the island with her parents Walt and Laura, both lawyers, and her three younger brothers in a house called Summer's End.

Sam and Suzy, both introverted, intelligent, and mature for their age, meet in the summer of 1964 during a church performance of Noye's Fludde and become pen pals. The relationship becomes romantic over the course of their correspondence, and they make a secret pact to reunite and run away together. In September 1965, they execute their plan. Sam escapes from Camp Ivanhoe while Suzy runs away from Summer's End. The pair rendezvous, hike, camp, and fish in the wilderness with the goal of reaching a specific location.

Meanwhile, the Khaki Scouts have become aware of Sam's absence, finding a letter he left behind stating he has resigned. Scout Master Ward tells the Khaki Scouts to use their skills to set up a search party and find Sam. Island Police Captain Duffy Sharp and Ward contact Sam's guardians the Billingsleys, learning they are actually his foster parents and Sam is an orphan with a history of behavioral issues at home.

Eventually, a group of Khaki Scouts confronts Sam and Suzy and tries to capture them. During the resulting altercation, Suzy injures the Scouts' de facto leader Redford with a pair of scissors, and a stray arrow fired by one of the Scouts kills Camp Ivanhoe's dog Snoopy. The Scouts flee, and Sam and Suzy hike to Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet which they name "Moonrise Kingdom." They set up camp and as the romantic tension between them grows, they dance on the beach and share each other's first kiss.

Suzy's parents, Ward, the Scouts, and Sharp finally find Sam and Suzy in their tent the next morning. Suzy's parents take her home. Ward gives Sam a letter from the Billingsleys stating that they no longer wish to house Sam. He stays with Sharp while they await the arrival of a Social Services worker, who will likely place Sam in an orphanage and possibly treat him with electroshock therapy.

While in their treehouse, the Camp Ivanhoe Scouts have a change of heart and decide to help Suzy and Sam. Together, they paddle to neighboring St. Jack Wood Island to seek out the help of Ben, an older cousin of the scout Skotak. Ben works at Fort Lebanon, a larger Khaki Scout summer camp on St. Jack Wood Island run by Ward's superior, Commander Pierce. Ben decides to try to take Sam and Suzy to a crabbing boat anchored off the island so that Sam can work as a crewman and avoid Social Services. He performs a "wedding" ceremony, which he admits is not legally binding, before they leave. Sam, Suzy, and Ben set off for the crabbing boat in a sailboat, but quickly return so that Sam can retrieve Suzy's binoculars. As Sam returns to the camp chapel to look for the binoculars, he is confronted by Redford, who alerts the camp to Sam and Suzy's presence. Suzy's parents, Captain Sharp, Social Services, and the Scouts of Fort Lebanon, under the command of Ward, pursue them.

A violent hurricane and flash flood strike, and Sharp apprehends Sam and Suzy on the steeple of the church in which they first met. Lightning destroys the steeple, but Sharp saves them. During the storm, he decides to become Sam's legal guardian. The hurricane erases Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet from the map. At Summer's End, Sam is upstairs painting a landscape of Moonrise Kingdom. Suzy and her brothers are called to dinner, while Sam slips out of the window to join Sharp in his patrol car, telling Suzy he will see her the following day.

Cast

- Bruce Willis as Captain Sharp

- Edward Norton as Scout Master Ward

- Bill Murray as Mr. Bishop

- Frances McDormand as Mrs. Bishop

- Tilda Swinton as Social Services

- Jason Schwartzman as Cousin Ben

- Bob Balaban as Narrator

- Jared Gilman as Sam

- Kara Hayward as Suzy

- Lucas Hedges as Redford

- Larry Pine as Howard Billingsley

- Marianna Bassham as Becky

- Neal Huff as Jed

- Eric Chase Anderson as Secretary McIntire

- Jake Ryan as Lionel

- Harvey Keitel as Commander Pierce

Production

Development

Director Wes Anderson had long been interested in depicting a romance between children.[2] He described the starting idea for the story as a memory of fantasized young love:

I remember this feeling, from when I was that age and from when I was in fifth grade, but nothing really happened. I just experienced the period of dreaming about what might happen, when I was at that age. I feel like the movie could really be something that was envisioned by one of these characters.[3]

When he was 12, Anderson lived in Texas with two brothers. His parents were separating, and influenced his later depictions of crumbling marriages.[2] He was briefly a Scout,[4] and had acted Noye's Fludde, an opera for children about Noah's Ark.[5] A childhood incident inspired the scene where Suzy reveals her parents' book Coping with the Very Troubled Child. He found a similarly titled book belonging to his father and remarked, "I immediately knew who that troubled child was."[6]

After working on the screenplay for a year, Anderson said he had completed 15 pages and appealed to his The Darjeeling Limited collaborator Roman Coppola for help; they finished in one month.[5] Coppola drew on memories of his mother Eleanor in giving Mrs. Bishop a bullhorn to communicate inside the house.[6] Anderson described the 1965 setting as randomly chosen, but added it fit the subject of the Scouts and the feel of a "Norman Rockwell-type of Americana".[7] While preparing the script Anderson also viewed films about young love for inspiration, including Black Jack, Small Change, A Little Romance and Melody.[8] François Truffaut's 1959 French film The 400 Blows about juvenile delinquency was also an influence.[2]

After his 2009 film Fantastic Mr. Fox underperformed, Anderson said he had to pitch Moonrise Kingdom with a smaller budget than he would have otherwise requested. The budget was US$16 million,[9] and his producers Steven Rales and Scott Rudin agreed to back the project.[10]

Casting

The crew scheduled a substantial amount of time for casting the Sam and Suzy characters. Anderson expressed apprehension about the process saying, "there's no movie, if we don't find the perfect kids".[3] The auditions took eight months at different schools.[2] Anderson chose Jared Gilman finding him "immediately funny" thanks to his glasses and long hair, and for his voice and personality at the audition. Kara Hayward was cast because she read from the screenplay and spoke naturally as if it was real life.[7] Hayward had seen Anderson's 2001 The Royal Tenenbaums and interpreted Suzy as having a secretive nature, similar to that of Margot played by Gwyneth Paltrow.[11] All the child actors were novices. Anderson believed they had never even auditioned before. He put the successful candidates through months-long rehearsals. He assigned Hayward book reading, and had Gilman practice scouting skills. Although Anderson could not envision one young auditioner, Lucas Hedges, as Sam, he felt the boy was talented enough to be given an important role and cast him as Redford.[6]

Bill Murray and Jason Schwartzman were regular actors in Anderson's filmography.[12][13] Schwartzman said he accepted the role of Cousin Ben without asking for a larger part, because in his experience Anderson always planned thoroughly what was best for his films, including casting characters.[13] Unlike Murray and Schwartzman, Bruce Willis, Edward Norton, Frances McDormand and Tilda Swinton had not worked with Anderson. Journalist Jacob Weisberg characterized them as "the ensemble cast".[14] While Anderson said that he wrote the part of Captain Sharp imagining the deceased James Stewart playing him, he thought Willis could be the "iconic policeman" once the screenplay was completed.[10] Willis said he had seen all of Anderson's films and was interested in collaborating with the director.[15] Anderson also hoped Norton would play Scout Master Ward, commenting, "he was somebody who I thought of as a scoutmaster ... He looks like he has been painted by Norman Rockwell."[4] In June 2011, it was reported Harvey Keitel joined the cast after most of the other principal actors.[16]

Pre-production

.jpg.webp)

In the film, 12-year-old Suzy packs six fictitious storybooks she stole from the public library. Six artists were commissioned to create the jacket covers for the books, and Wes Anderson wrote passages for each of them. Suzy is shown reading aloud from three of the books during the film. Anderson had considered incorporating animation for the reading scenes but chose to show her reading with the other actors listening spellbound. In April 2012, Anderson decided to animate all six books and use them in a promotional video where the film's narrator Bob Balaban introduces each segment.[17]

Anderson described designing the maps for the fictitious New Penzance Island and St. Jack Wood Island saying: "It's weird because you'd think that you could make a fake island and map it, and it would be a simple enough matter, but to make it feel like a real thing, it just always takes a lot of attention."[18] In addition to the books and maps, Anderson said the crew spent a substantial amount of time creating the watercolor paintings, needle-points and other original props. He wanted to ensure that even if a prop is only briefly seen in the film "you kind of feel whether or not they've got the layers of the real thing in them".[18]

.jpg.webp)

Anderson used Google Earth for initial location scouting, searching for places where they could find Suzy's house and "naked wildlife", considering Canada, Michigan and New England. The filmmakers running the Google search also looked at Cumberland Island in Georgia, and the Thousand Islands.[19] Camp Yawgoog, an actual Scout camp in Rhode Island, served as the inspiration for the Khaki Scout sets, and many items were borrowed from the camp for props.[20]

Kasia Walicka-Maimone was the costume designer. Anderson presented her with concepts of how the characters should look. She drew on photographs from the 1960s and the uniforms of Boy Scouts when designing Suzy and Sam's costumes. (Their characters inspired many Halloween costumes in 2012.)[21] While the filmmakers planned to model the animal costumes on those in real Noye's Fludde productions, they decided instead to fashion them as if they were made for U.S. schools, consulting photographs from Anderson's former school.[20]

Filming

Principal photography took place in Rhode Island from April to June 2011.[22] The film was shot at various locations around Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, including: Conanicut Island, Prudence Island, Fort Wetherill, Yawgoog Scout Reservation, Trinity Church, and Newport's Ballard Park.[23][24] A house in the Thousand Islands region in New York was used as the model for the interior of Suzy's house on the film's set. The set for the Bishop home was constructed and filmed inside a former Linens 'n Things store in Middletown, Rhode Island.[25][23] Conanicut Island Light, a decommissioned Rhode Island lighthouse, was used for the exterior.[19] Cinematographer Robert Yeoman shot the film on Super 16mm with a 1.85:1 aspect ratio, as opposed to Anderson's usual 35mm anamorphic format, using Aaton Xterà and A-Minima cameras.[26] Anderson said the Aaton cameras were ideal for photographing child actors, as they were roughly the same height as the camera set up.[5]

According to Anderson, the kissing scene between Sam and Suzy was not rehearsed so it could be "spontaneous"; it was the first kiss, on or off screen, for both actors.[27][28] Hayward was given the cat seen in the film as a pet after the production was concluded.[11]

Themes

Professor Peter C. Kunze wrote that the story depicts "preteen romance", exploring child sexuality in the vein of The Blue Lagoon.[29] Several critics interpreted the ear-piercing scene as symbolizing the characters losing their virginity.[30][31] Author Carol Siegel judged the portrayal to be a positive take on "youthful sexual initiation", from a mainly male perspective, but like many other U.S. films she said it missed a female perspective.[32] Academic Timothy Shary placed the story in the cinematic tradition of exploring "young romance" and the resulting strife, with Titanic (1997) and Boys Don't Cry (1999).[33]

The film scholar Kim Wilkins rejected the notion that Moonrise Kingdom is a romance film. She argued the severity of Sam and Suzy's behavior, and their "profound existential anxiety", indicate the characters were created as products of a more widespread concern for juvenile mental health. Wilkins wrote that the story dealt with "existential" questions, with the two young protagonists rejected by society and allying to escape to "a limited existence beyond its boundaries".[34] According to a Chicago Tribune analysis, Moonrise Kingdom represented Anderson's most focused study on a theme running through his work, "the feelings of misunderstood, unconventional children".[35]

J.M. Tyree of Film Quarterly argued the story illustrated both an affinity with and "arch skepticism" of the "comedy of love", where in Shakespearean comedy lovers, after courtship and marriage, would "return to a reconstituted civilized order". Sam and Suzy escape civilization but are always taken "back into twisted knots of communal ties".[36] Critic Geoffrey O'Brien wrote that, while camps are common settings for stories about "innocence" lost, the truer theme was "the awakening of the first radiance of mature intelligence in a world liable to be indifferent or hostile to it".[37]

The narrative features collapsing families,[38] represented by the Bishops' failing marriage. Professor Emma Mason suggested their large house serves as a "mausoleum-like shelter".[39] Sam is also disowned by his foster family for behaviors like arson while sleepwalking. While he told Suzy "I feel like I'm in a family now", academic Donna Kornhaber argued Sam, as an orphan, has a realistic perspective on the difficulties of building a family.[38] As an adoptive father Sharp may not be ready, Tyree wrote, "but [his] lack of self-centeredness sets him apart from other would-be fathers or mentors in Anderson's world".[36]

Professor Laura Shakelford observed how Suzy as the raven in Noye's Fludde is followed by a historic rainstorm echoing Noah's flood.[40] Scholar Anton Karl Kozlovic suggested that while the film includes no quotes from the Book of Genesis and no shots of a copy of the Book, Noah's story is used for symbolism. The children dress as animals before floods cause them to seek shelter in the church, Kozlovic observed.[41] Following the Genesis narrative, after the New Penzance flood, there is "abundant regeneration" with great harvests of high-quality produce.[42] Shakelford read the story as a commentary on the characters grappling with the relationship between "the material world" in "postmodern cultures" and that of animals.[40]

Style

.jpg.webp)

Academic James MacDowell evaluated the film's style as displaying "the director's trademark flat, symmetrical, tableau framings of carefully arranged characters within colorful, fastidiously decorated sets" with "patent unnaturalism and self-consciousness".[43] Considering the emphasis on symmetry (as opposed to other photographic composition strategies such as the rule of thirds) and color, authors Stephanie Williams and Christen Vidanovic wrote, "Almost every frame in this movie could be a beautiful photograph."[44] Critic Robbie Collin added that besides the symmetry, many shots are "busy with detail, and if something visually dull has to happen, Anderson embellishes it: when Sam and Suzy retreat to have a quiet heart-to-heart, he places their silent conversation on the left hand side of the frame and an enthusiastic young trampolinist on the right".[45] Roger Ebert identified the color scheme as emphasizing green in the grass, khaki in the Scouts camp and uniforms, and some red, creating "the feeling of magical realism".[46]

Scholar Nicolas Llano Linares wrote that Anderson's films are "distinctively andersonian to the limit", "filled with ornate elements that create particular worlds that define the tone of the story, the visual and material dimensions of his sets". Linares particularly commented on the use of the animated maps, which make Anderson's universe more credible, and also have metaphorical significance.[47] Macdowell pointed to the characters' books and the production of Noye's Fludde as examples of the "indulgent, excessive, yet attractive neatness" that children in Anderson's films enjoy. He also interpreted the animated maps as showing a naïve style.[43]

In the scene where the Khaki Scouts meet with Cousin Ben, writer Michael Frierson observed how the tracking shot is combined with "clipped, military dialogue". The tents in the background in the tracking shot are in symmetry. Frierson also judged the moving camera as "smooth, stabilized".[48] Joshua Gooch observed the dissolve between Sam's artwork and the Moonrise Kingdom beach tied together art with desire.[49]

The dialogue is similarly "stylized" and "mannered" as in other Anderson films, which O'Brien viewed as fitting for "alienated twelve-year-olds who, on top of everything else, must invent a way to communicate with each other".[37] This dialogue is spoken with "self-aware deadpan" performances.[50]

Soundtrack

Alexandre Desplat composed the original score, with percussion compositions by frequent Anderson collaborator Mark Mothersbaugh.[51] The film's final credits feature a deconstructed rendition of Desplat's original soundtrack in the style of English composer Benjamin Britten's Young Person's Guide, accompanied by a child's voice to introduce each instrumental section.[52]

The soundtrack also features music by Britten, a composer notable for his many works for children's voices. At Cannes, during the post-screening press conference, Anderson said: "The Britten music had a huge effect on the whole movie, I think. The movie's sort of set to it. The play of Noye's Fludde that is performed in it—my older brother and I were actually in a production of that when I was ten or eleven, and that music is something I've always remembered, and made a very strong impression on me. It is the color of the movie in a way.[53]

With many Britten tracks taken from recordings conducted or supervised by the composer himself, the music includes The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra (Introduction/Theme; Fugue), conducted by Leonard Bernstein; Friday Afternoons ("Cuckoo"; "Old Abram Brown"); Simple Symphony ("Playful Pizzicato"); Noye's Fludde (various excerpts, including the processions of animals into and out of the ark, and "The spacious firmament on high"); and A Midsummer Night's Dream ("On the ground, sleep sound").[54] Also featured are extracts from Saint-Saëns's Le Carnaval des animaux, Franz Schubert's "An die Musik", Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera Così fan tutte and tracks by Hank Williams.[55] The soundtrack album reached number 187 on Billboard's Top Current Albums chart.[56]

Release

Focus Features acquired world rights to the independently produced film.[22] Moonrise Kingdom premiered on May 16, 2012, as the opening film at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival,[57] Anderson's first film to be screened there.[8] Studio Canal released the film in French theaters on the same day.[58] The U.S. limited release followed on May 25,[12] in New York City and Los Angeles.[9] A short film, Cousin Ben Troop Screening with Jason Schwartzman, also directed by Anderson, was released on Funny or Die to promote the film.[59] By its fifth week, the release was expanded to 395 theaters.[9]

In Region 1 Moonrise Kingdom was released on DVD and Blu-ray by Universal Studios Home Entertainment on October 16, 2012, with featurettes like "A Look Inside Moonrise Kingdom".[60] The Criterion Collection released both a DVD and Blu-ray with a 2K restoration on September 22, 2015.[61]

Reception

Box office

In its opening weekend, Moonrise Kingdom earned $523,006 in four theaters, setting a record for the greatest gross per theater average for a live action film of $167,371.[62][63] After five weeks, it made $11.6 million.[9] By September, it grossed $43.7 million, doubling that of Anderson's Fantastic Mr. Fox.[64]

Finishing its theatrical run on November 1, 2012, Moonrise Kingdom had grossed $45,512,466 domestically and $22,750,700 in international markets for a worldwide total of $68,263,166.[65] It was Anderson's highest-grossing film in North America.[66]

Critical response

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 94% based on reviews from 262 critics, with an average score of 8.24/10. The consensus states, "Warm, whimsical, and poignant, the immaculately framed and beautifully acted Moonrise Kingdom presents writer/director Wes Anderson at his idiosyncratic best."[67] Review aggregation website Metacritic gives the film a weighted average score of 84 out of 100, based on 43 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[68] Moonrise Kingdom was also listed on many critics' top 10 lists of the year.[69] In 2016, it was voted 95th in an international critics' poll, the BBC's 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century.[70]

Roger Ebert rated the film three-and-a-half stars, praising the creation of an island world that "might as well be ruled by Prospero".[46] A devoted fan of Anderson, Richard Brody hailed Moonrise Kingdom as "a leap ahead, artistically and personally" for the director, for its "expressly transcendent theme" and its spiritual references to Noah's Ark.[71] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gave the film four stars out of five, calling it "another sprightly confection of oddities, attractively eccentric, witty and strangely clothed".[72] The New York Times's Manohla Dargis reviewed Anderson and Coppola's screenplay as a "beautifully coordinated admixture of droll humor, deadpan and slapstick".[73] Peter Travers positively reviewed the actors' performances, calling Norton engaging, Balaban "delightful" and Willis agreeable. Travers also credited cinematographer Yeoman for "a poet's eye" and composer Alexandre Desplat for his contributions.[74] As novice actors, Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward also received praise.[75] The Daily Telegraph's review stated it was "exhilarating" to see different elements combined, such as the music of Britten and Hank Williams. It called the end result "an extraordinarily affected piece of filmmaking".[45] The Hollywood Reporter's review by Todd McCarthy described the film as an "eccentric, pubescent love story", "impeccably made".[76] For Empire, Nev Pierce declared it "a delightful film of innocence lost and regained".[77] Christopher Orr of The Atlantic wrote that Moonrise Kingdom was "Anderson's best live-action feature" and that it "captures the texture of childhood summers, the sense of having a limited amount of time in which to do unlimited things".[78] Kristen M. Jones of Film Comment wrote that the film "has a spontaneity and yearning that lend an easy comic rhythm", but it also has a "rapt quality, as if we are viewing the events through Suzy's binoculars or reading the story under the covers by a flashlight".[79]

Dissenting, Leonard Maltin wrote the "self-consciously clever to a fault" approach to depicting the children gave him "an emotional distance" to them.[80] Rex Reed dismissed it as "juvenile gibberish" displaying "lunatic fragments of surrealism".[81] Postmedia News' Katherine Monk gave a mixed review, calling it "kind-hearted and heavily contrived".[82]

In later years, IndieWire placed Scout Master Ward in Anderson's top 10 most memorable characters in 2015, at ninth place, calling him "completely charming"; the same list also identified Suzy as "one of Anderson's best-drawn female characters".[83] Chuck Bowen of Slant Magazine judged Moonrise Kingdom and The Grand Budapest Hotel as exemplifying Anderson's new leaner style (compared to what Bowen called "bloated speechifying" of past films) and credited editor Andrew Weisblum for "precise, unsentimental editing".[84] In 2018, Variety named Moonrise Kingdom as Anderson's seventh best of nine films, saying Sam and Suzy did not feel real.[85]

Accolades

.jpg.webp)

At Cannes, the film was in competition for the Palme d'Or,[86] although the only award it won there was the unofficial "Palme de Whiskers" in recognition of the cat, "Tabitha".[87] In anticipation of the 85th Academy Awards, journalist Lindsey Bahr called Moonrise Kingdom a "wild card" in the awards campaign given it received no nominations at the Screen Actors Guild or Directors Guild, but had won the Gotham Independent Film Award for Best Feature.[88] Early in the campaign, it was a contender for a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture.[89] Anderson and Coppola were ultimately nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[90]

The film was also nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[91] It received five nominations at the 28th Independent Spirit Awards, including for Best Feature,[92] and two nominations at the 17th Satellite Awards, including Best Film.[93]

Controversy

The Huffington Post journalist Mina Zaher criticized the depiction of the sexual awakening between Sam and Suzy, expressing discomfort with the scene where Sam touches Suzy's breasts, calling it "a step further or perhaps too far". Zaher questioned if the children's sexuality could have been portrayed in a more appropriate way.[94] Reviewing the scene where the characters dance wearing only their underwear, the Catholic News Service stated "The interlude doesn't quite cross over into the full-blown exploitation of children, but it teeters on that edge".[95] Professor Carol Siegel summed up the portrayal as "delicate and to a large extent inoffensive".[96]

In one scene, the dog Snoopy is killed by an arrow in a scene compared to Lord of the Flies by William Golding.[97] This inspired a New Yorker editorial by Ian Crouch, "Does Wes Anderson Hate Dogs?". Crouch said that in the theater where he saw the film, "the shot showing the dog impaled and inert elicited a shocked, yelping exhale from many people in the audience", and he observed outrage on Twitter.[98] The Washington Post critic Sonia Rao held up Snoopy's death as a prime example of "[A] particular kind of darkness [that] lurks" in Anderson's filmography, where "[p]ets are so often the victims of the writer-director's quirky storytelling", but argued Anderson's 2018 Isle of Dogs served to remedy this.[99]

References

- "Moonrise Kingdom (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. May 8, 2012. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- Clarke, Cath (2012). "Wes Anderson interview". Time Out. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Radish, Christina (June 5, 2012). "Wes Anderson Talks Moonrise Kingdom, His Next Film, Doing Another Stop-Motion Movie and More". Collider. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Wes Anderson, Creating A Singular 'Kingdom'". NPR. February 15, 2013. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Lyttelton, Oliver (May 23, 2012). "The Playlist Interview From Cannes: Wes Anderson Discusses The Nostalgia, Music, & Making Of 'Moonrise Kingdom'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Miller, Julie (June 22, 2012). "Wes Anderson on Moonrise Kingdom, First Loves, and Cohabitating with Bill Murray". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Kilday, Gregg (May 15, 2012). "Cannes 2012: Wes Anderson on Making 'Moonrise Kingdom' and His Cannes Debut (Q&A)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Hornaday, Ann (June 2, 2012). "Wes Anderson talks about 'Moonrise Kingdom' and his Cannes debut". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- Cunningham, Todd (August 9, 2012). "Behind 'Moonrise Kingdom's' Unconventional But Steady March to the Oscars". The Wrap. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Fleming, Mike Jr. (June 5, 2012). "Fleming Q&A's 'Moonrise Kingdom' Director Wes Anderson". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Buchanan, Kyle (May 30, 2012). "Meet the Kids From Moonrise Kingdom, Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Allin, Olivia (January 13, 2012). "Bill Murray and Wes Anderson reunite for 'Moonrise Kingdom'". On the Red Carpet. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Yuan, Jada (May 29, 2012). "Jason Schwartzman on Ghost Stories, Boy Scouts, and Ignoring the Moonrise Kingdom Kids". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Weisberg, Jacob (May 17, 2012). "Wes Anderson on directing Bruce Willis, Edward Norton for the first time". Slate. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Willis, Bruce (2012). A Look Inside Moonrise Kingdom. Moonrise Kingdom (Blu-ray). Entertainment One Films Canada.

- Matt, Goldberg (June 7, 2011). "New Set Photos for Wes Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom; Harvey Keitel Confirmed to Join Cast". Collider. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- Vary, Adam (June 7, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom': Wes Anderson's animated take on the film's imaginary books". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- Vary, Adam (June 1, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom' director Wes Anderson on its box office record and casting his young leads". Inside Movies. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- Karpel, Ari (July 3, 2012). "Moving Storyboards and Drumming: Wes Anderson Maps Out the Peculiar Genius of "Moonrise Kingdom"". Fast Company. Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- Brunner, Rob (June 1, 2012). "The Whimsical Mr. Anderson". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1209–1210. p. 101.

- Teran, Andi (February 19, 2013). "An Exclusive Interview with Kasia Walicka-Maimone, Costume Designer of 'Moonrise Kingdom'". MTV. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Thompson, Anne (May 2, 2011). "Wes Anderson's New Movie Moonrise Kingdom Starring Willis, Norton, and Murray Goes to Focus Features". IndieWire. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ""Moonrise Kingdom" release is set". The Newport Daily News. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- Sullivan, Jennifer Nicole (June 6, 2012). "Enchanted "Kingdom"". The Newport Daily News. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- Muther, Christopher. "Creating "Moonrise Kingdom" in Rhode Island with Wes Anderson's production designer Adam Stockhausen - The Boston Globe". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- Heuring, David (May 25, 2012). "Cinematographer Robert Yeoman Talks Super 16 Style on Moonrise Kingdom". Studio Daily. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- Ryzik, Melena (December 20, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom's' Magical, Nerve-Racking Moment". The Carpetbagger. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- Widdicombe, Lizzie (May 28, 2012). "Newbie". The New Yorker. pp. 25–26.

- Kunze 2014, p. 100.

- Dilley 2017.

- Examples:

- Frosch, Jon (May 16, 2012). "Wes Anderson's 'Moonrise Kingdom' Opens Cannes on a Sweet Note". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

Sam pierces Suzy's ears with fish hooks, adorning her with hand-crafted insect earrings as a fine stream of blood trickles down her neck (a mutual deflowering by proxy).

- Adams, Sam (May 16, 2012). "The best films of 2012". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

Pushing the barbed hooks through her unpierced lobes works as a canny metaphor for deflowering.

- Dargis, Manohla (May 24, 2012). "Scouting Out a Paradise: Books, Music and No Adults". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

[T]hey consummate, metaphorically, an enchanted, chaste affair capped with a hilariously symbolic deflowering.

- Frosch, Jon (May 16, 2012). "Wes Anderson's 'Moonrise Kingdom' Opens Cannes on a Sweet Note". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Siegel 2015, p. 55.

- Shary 2014, p. 10.

- Wilkins 2014, p. 26.

- "Bill Murray talks about a director he likes, Wes Anderson of 'Moonrise Kingdom'". Chicago Tribune. May 16, 2012. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Tyree, J.M. (Summer 2013). "Unsafe Houses: Moonrise Kingdom and Wes Anderson's Conflicted Comedies of Escape". Film Quarterly. 66 (4). doi:10.1525/fq.2013.66.4.23. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- O'Brien, Geoffrey (September 22, 2015). "Moonrise Kingdom: Awakenings". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Kornhaber 2017.

- Mason 2016.

- Shakelford 2014, p. 199.

- Kozlovic 2016, p. 47.

- Reinhartz 2013, p. 135.

- Macdowell 2014, p. 158.

- Williams & Vidanovic 2013, p. 95.

- Collin, Robbie (May 25, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom, review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (May 30, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Linares 2016.

- Frierson 2018.

- Gooch 2014, p. 196.

- Buckwalter, Ian (May 24, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom': Quirk, And An Earnest Heart". NPR. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Perez, Rodrigo (May 25, 2012). "Make Your Own Mixtape: 17 Songs From Wes Anderson's Films That Are Not On The Official Soundtracks". IndieWire. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Platt, Russell (August 6, 2012). "Benjamin Britten's 'Moonrise Kingdom'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- "Moonrise Kingdom: What's the Britten music used in Wes Anderson's new movie?". Britten Pears Foundation. 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Minske, Evan (May 2, 2012). "Wes Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom Soundtrack: Check Out the Tracklist and a Piece of the Score". Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- Kurp, Josh (May 2, 2012). "Is the Soundtrack for 'Moonrise Kingdom' the Most Wes Anderson-y Soundtrack Yet?". Uproxx. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- "Top Current Albums". Billboard.biz. July 21, 2012. Archived from the original on October 22, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- Leffler, Rebecca (May 16, 2012). "Cannes 2012: Film Festival Kicks Off With World Premiere of Wes Anderson's 'Moonrise Kingdom'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Knegt, Peter (March 8, 2012). "Wes Anderson's 'Moonrise Kingdom' To Open Cannes". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Jagernauth, Kevin (June 19, 2012). "Watch: Jason Schwartzman's Cousin Ben Hosts A Screening Of 'Moonrise Kingdom' In Wes Anderson-Directed Video". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Shaffer, R.L. (August 15, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom Explores BD, DVD". IGN. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- Lattanzio, Ryan (June 25, 2015). "See Criterion's Wondrous New 'Moonrise Kingdom' Cover Art". Indiewire. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Smith, Grady (May 28, 2012). "Box office report: 'Men in Black 3' tops Memorial Day weekend with $70M; 'Moonrise Kingdom' huge in limited release". Inside Movies blog. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- Pomerantz, Dorothy (May 29, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom' and the Value of Limited Release". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 1, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Smith, Grady; Staskiewicz, Keith (September 7, 2012). "Summer Box Office Winners & Losers". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1223. pp. 14–15.

- "Moonrise Kingdom". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 20, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Khatchatourian, Maane (April 14, 2014). "'Grand Budapest Hotel' Hits $100 Mil, Becomes Wes Anderson's Highest-Grossing Pic". Variety. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- "Moonrise Kingdom (2012)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- "Moonrise Kingdom". Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Dietz, Jason (December 11, 2012). "2012 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- "The 21st century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- Brody, Richard (December 11, 2012). "What to See This Weekend: 'Moonrise Kingdom,' Twice". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Bradshaw, Peter (May 24, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom – review". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- Dargis, Manohla (May 24, 2012). "Scouting Out a Paradise: Books, Music and No Adults". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Travers, Peter (May 24, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Examples:

- Craig, Justin (May 25, 2012). "Review: Superb 'Moonrise Kingdom' filled with childhood innocence, great performances". Fox News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward as Sam and Suzy give two breakout performances. Gilman and Hayward, carrying the weight of the film on their shoulders, handle Anderson's offbeat style with grace and ease and are a delight to watch.

- Howell, Peter (May 31, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom review: Wes Anderson's moon-cross'd lovers". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

No Hollywood gleam can outshine the fresh faces of Gilman and Hayward, newly hatched thespians who bring a refreshing lack of guile to their roles.

- Sharkey, Betsy (May 25, 2012). "Review: Wes Anderson finds near perfect balance in 'Moonrise Kingdom'". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

[I]n Gilman and Hayward we have rare young talents who don't need words to communicate what they're feeling.

- Craig, Justin (May 25, 2012). "Review: Superb 'Moonrise Kingdom' filled with childhood innocence, great performances". Fox News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- McCarthy, Todd (May 16, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom: Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- Pierce, Nev (March 1, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom Review". Empire. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Orr, Christopher (June 1, 2012). "The Youthful Magic of 'Moonrise Kingdom'". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 9, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- Jones, Kristen M. "Moonrise Kingdom". Film Comment. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- Maltin, Leonard (May 25, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom—movie review". IndieWire. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Reed, Rex (May 23, 2012). "In Moonrise Kingdom, Watercolors Run Dry". New York Observer. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Monk, Katherine (June 1, 2012). "Review: Moonrise Kingdom". Postmedia News. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Kiang, Jessica; Lyttelton, Oliver (September 24, 2015). "Ranked: Wes Anderson's Most Memorable Characters". IndieWire. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- Bowen, Chuck (September 21, 2015). "Review: Moonrise Kingdom". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Wes Anderson Films Ranked — From Worst to Best". Variety. 2018. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Festival de Cannes - From 16 to 27 may 2012". Festival-cannes.fr. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Winfrey, Graham (May 30, 2017). "Agnès Varda's 'Faces Places' Cat Wins Palme de Whiskers at Cannes 2017". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- Bahr, Lindsey (January 9, 2013). "'Moonrise Kingdom' director Wes Anderson would care about awards if ..." Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Haglund, David (November 27, 2018). "Can Moonrise Kingdom Get a Best Picture Nod?". Slate. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Hammond, Pete (January 22, 2013). "Exclusive Featurette: Original Screenplay Oscar Nominee 'Moonrise Kingdom'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- "2013 Golden Globe Nominations". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. December 14, 2012. Archived from the original on December 17, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- Harp, Justin (November 27, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom', 'Silver Linings' among Independent Spirit nominees". Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines UK. Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- Harp, Justin (December 4, 2012). "'Les Misérables' earns ten Satellite Award nominations". Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines UK. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- Zaher, Mina (May 28, 2012). "Why Moonrise Kingdom Made Me Feel Uncomfortable". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Jensen, Kurt (June 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Siegel 2015, p. 56.

- Examples:

- Clarke, Cath (2012). "Wes Anderson interview". Time Out. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

[I]t all goes a bit Lord of the Flies: Suzy stabs a boy in the kidney with left-handed scissors.

- White, Sharr (December 18, 2012). "Sharr White on 'Moonrise Kingdom' by Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola". Variety. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

Anderson flirts with what could be true danger—a Lord of the Flies assemblage of Boy Scouts mounting a violent frontal assault against our protagonists.

- Crouch, Ian (June 21, 2012). "Does Wes Anderson Hate Dogs?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

The lone fatality is Snoopy, a handsome wire-hair fox terrier, who during a spat of Lord of the Flies-style violence among some children takes an errant arrow in the neck.

- Clarke, Cath (2012). "Wes Anderson interview". Time Out. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Crouch, Ian (June 21, 2012). "Does Wes Anderson Hate Dogs?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- Rao, Sonia (March 22, 2018). "Bad things happen to pets in Wes Anderson movies. 'Isle of Dogs' tries to make up for that". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

Bibliography

- Dilley, Whitney Crothers (2017). "Introduction: Wes Anderson as Auteur". Cinema of Wes Anderson: Bringing Nostalgia to Life. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231543200.

- Frierson, Michael (2018). "Rhythmic and Graphic Editing". Film and Video Editing Theory: How Editing Creates Meaning. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1315474991.

- Gooch, Joshua (2014). "Objects/Desire/Oedipus: Wes Anderson as Late Capitalist Auteur". In Peter C. Kunze (ed.). The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon. Springer. ISBN 978-1137403124.

- Kornhaber, Donna (2017). "Moonrise Kingdom". Wes Anderson. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252099755.

- Kozlovic, Anton Karl (2016). "Noah and the Flood: A Cinematic Deluge". In Rhonda Burnette-Bletsch (ed.). The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-1614513261.

- Kunze, Peter C. (2014). "From the Mixed-Up Films of Mr. Wesley W. Anderson: Children's Literature as Intertexts". In Peter C. Kunze (ed.). The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon. Springer. ISBN 978-1137403124.

- Linares, Nicolas Llano (2016). "Emotional Territories: An Exploration of Wes Anderson's Cinemaps". In Anna Malinowska; Karolina Lebek (eds.). Materiality and Popular Culture: The Popular Life of Things. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317219125.

- Macdowell, James (2014). "The Andersonian, The Quirky, and Innocence". In Peter C. Kunze (ed.). The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon. Springer. ISBN 978-1137403124.

- Mason, Emma (2016). "Wes Anderson's Messianic Elegies". In Mark Knight (ed.). The Routledge Companion to Literature and Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135051099.

- Reinhartz, Adele (2013). Bible and Cinema: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1134627011.

- Shakelford, Laura (2014). "Systems Thinking in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and Moonrise Kingdom". In Peter C. Kunze (ed.). The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon. Springer. ISBN 978-1137403124.

- Shary, Timothy (2014). Generation Multiplex: The Image of Youth in American Cinema Since 1980 (Revised ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292756625.

- Siegel, Carol (2015). Sex Radical Cinema. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253018113.

- Wilkins, Kim (2014). "Cast of Characters". In Peter C. Kunze (ed.). The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon. Springer. ISBN 978-1137403124.

- Williams, Stephanie; Vidanovic, Christen (2013). This Modern Romance: The Artistry, Technique, and Business of Engagement Photography. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1134100590.