Second Council of Constantinople

The Second Council of Constantinople is the fifth of the first seven ecumenical councils recognized by both the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church. It is also recognized by the Old Catholics and others. Protestant opinions and recognition of it are varied. Some Protestants, such as Calvinists, recognize the first four councils,[2] whereas Lutherans and most Anglo-Catholics accept all seven. Constantinople II was convoked by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I under the presidency of Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople. It was held from 5 May to 2 June 553. Participants were overwhelmingly Eastern bishops—only sixteen Western bishops were present, including nine from Illyricum and seven from Africa, but none from Italy—out of the 152 total.[1][3]

| Second Council of Constantinople | |

|---|---|

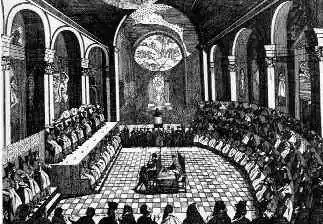

Artistic rendition of Second Council of Constantinople by Vasily Surikov | |

| Date | 553 |

| Accepted by |

|

Previous council | Council of Chalcedon |

Next council | Third Council of Constantinople |

| Convoked by | Emperor Justinian I |

| President | Eutychius of Constantinople |

| Attendance | 152[1] |

| Topics | Nestorianism Origenism |

Documents and statements | 14 canons on Christology and against the Three Chapters. 15 canons condemning the teaching of Origen and Evagrius. |

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

| Part of a series on the |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| 4th–5th centuries |

| 6th–9th centuries |

| 12th–14th centuries |

| 15th–16th centuries |

| 19th–20th centuries |

|

|

The main work of the council was to confirm the condemnation issued by edict in 551 by the Emperor Justinian against the Three Chapters. These were the Christological writings and ultimately the person of Theodore of Mopsuestia (died 428), certain writings against Cyril of Alexandria's Twelve Anathemas accepted at the Council of Ephesus, written by Theodoret of Cyrrhus (died c. 466), and a letter written against Cyrillianism and the Ephesian Council by Ibas of Edessa (died 457).[4]

The purpose of the condemnation was to make plain that the Great Church, which followed a Chalcedonian creed, was firmly opposed to Nestorianism as supported by the Antiochene school which had either assisted Nestorius, the eponymous heresiarch, or had inspired the teaching for which he was anathematized and exiled. The council also condemned the teaching that Mary could not be rightly called the Mother of God (Greek: Theotokos) but only the mother of the man (anthropotokos) or the mother of Christ (Christotokos).[4]

The Second Council of Constantinople is also considered as one of the many attempts by Byzantine Emperors to bring peace in the empire between the Chalcedonian and Monophysite fractions of the church which had been in continuous conflict since the times of the Council of Ephesus in AD 431.

Proceedings

The council was presided over by Eutychius, Patriarch of Constantinople, assisted by the other three eastern patriarchs or their representatives.[5] Pope Vigilius was also invited; but even though he was at this period resident in Constantinople (to avoid the perils of life in Italy, convulsed by the war against the Ostrogoths), he declined to attend, and even issued a document forbidding the council from proceeding without him (his 'First Constitutum'). For more details see Pope Vigilius.[6]

The council, however, proceeded without the pope to condemn the Three Chapters. And during the seventh session of the council, the bishops had Vigilius stricken from the diptychs for his refusal to appear at the council and approve its proceedings, effectively excommunicating him personally but not the rest of the Western Church. Vigilius was then imprisoned in Constantinople by the emperor and his advisors were exiled. After six months, in December 553, he agreed, however, to condemn the Three Chapters, claiming that his hesitation was due to being misled by his advisors.[4] His approval of the council was expressed in two documents, (a letter to Eutychius of Constantinople on 8 December 553, and a second "Constitutum" of 23 February 554, probably addressed to the Western episcopate), condemning the Three Chapters,[7] on his own authority and without mention of the council.[3]

In Northern Italy the ecclesiastical provinces of Milan and Aquileia broke communion with Rome. Milan accepted the condemnation only toward the end of the sixth century, whereas Aquileia did not do so until about 700.[3][8] The rest of the Western Church accepted the decrees of the council, though without great enthusiasm. Though ranked as one of the ecumenical councils, it never attained in the West the status of either Nicaea or Chalcedon.

In Visigothic Spain (Reccared having converted a short time prior) the churches never accepted the council;[9] when news of the later Third Council of Constantinople was communicated to them by Rome it was received as the fifth ecumenical council,[10] not the sixth. Isidore of Seville, in his Chronicle and De Viris Illustribus, judged Justinian a tyrant and persecutor of the orthodox[11] and an admirer of heresy,[12] contrasting him with Facundus of Hermiane and Victor of Tunnuna, who was considered a martyr.[13]

Despite the conflict between the council and the pope, and the inability to reconcile Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians, the council still made a significant theological contribution. The canons condemning the Three Chapters were preceded by ten dogmatic canons which defined Chalcedonian Christology with a new precision, bringing out that Christ has two natures, the human and the divine, in one person. The 'two natures' defined at Chalcedon were now clearly interpreted as two sets of attributes possessed by a single person, Christ God, the Second Person of the Trinity.[14] Later Byzantine Christology, as found in Maximus the Confessor and John of Damascus, was built upon this basis. It might have proved sufficient, moreover, to bring about the reunion of Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians, had it not been for the severance of connections between the two groups that resulted from the Muslim conquests of the next century.

Acts

The original Greek acts of the council are lost,[15] but an old Latin version exists, possibly made for Vigilius, of which there is a critical edition[16] and of which there is now an English translation and commentary,[17] and a modern Greek translation and commentary.[18] It has been alleged (probably falsely) that the original Acts of the Fifth Council had been tampered with[19] in favour of Monothelitism.[3] It used to be argued that the extant acts are incomplete, since they make no mention of the debate over Origenism. However, the solution generally accepted today is that the bishops signed the canons condemning Origenism before the council formally opened.[20] This condemnation was confirmed by Pope Vigilius and the subsequent ecumenical council (third Council of Constantinople) gave its "assent" in its Definition of Faith to the five previous synods, including "... the last, that is the Fifth holy Synod assembled in this place, against Theodore of Mopsuestia, Origen, Didymus, and Evagrius ...";[21] its full conciliar authority has only been questioned in modern times.[22]

There is a Syriac account of the council in the Melkite Chronicle of 641.[23]

Also, one of the Acts of the Council at Constantinople, were the Anathemas issued against those who rejected the Perpetual Virginity of Mary.[24]

Aftermath

Justinian hoped that this would contribute to a reunion between the Chalcedonians and Monophysites in the eastern provinces of the Empire. Various attempts at reconciliation between these parties within the Byzantine Empire were made by many emperors over the four centuries following the Council of Ephesus, none of them successful. Some attempts at reconciliation, such as this one, the condemnation of the Three Chapters and the unprecedented posthumous anathematization of Theodore—who had once been widely esteemed as a pillar of orthodoxy—causing further schisms and heresies to arise in the process, such as the aforementioned schism of the Three Chapters and the emergent semi-monophysite compromises of monoenergism and monotheletism. These propositions assert, respectively, that Christ possessed no human energy but only a divine function or principle of operation (purposefully formulated in an equivocal and vague manner, and promulgated between 610 and 622 by the Emperor Heraclius under the advice of Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople) and that Christ possessed no human will but only a divine will, "will" being understood to mean the desires and appetites in accord with the nature (promulgated in 638 by the same and opposed most notably by Maximus the Confessor).[4]

Notes

- "NPNF2–14. The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Introduction". CCEL. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- (3 names, 3 bishops and 145 other, plus 1 pope, total 152)

- See, e.g. Lutheran–Orthodox Joint Commission, Seventh Meeting, The Ecumenical Councils, Common Statement, 1993, available at Lutheran–Orthodox Joint Commission (B. I. 5a. "We agree on the doctrine of God, the Holy Trinity, as formulated by the Ecumenical Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople and on the doctrine of the person of Christ as formulated by the first four Ecumenical Councils.").

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Thomas J. Shahan (1913). "Councils of Constantinople". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Thomas J. Shahan (1913). "Councils of Constantinople". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Leo Donald Davis (1983), "Chapter 6 Council of Constantinople II, 553", The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787): Their History and Theology, Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, pp. 242–248, ISBN 978-0814656167, retrieved 2014-08-23

- Meyendorff 1989, pp. 241–243.

- "Vigilius | pope | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, vol. IX, pp. 414–420, 457–488; cf. Hefele, Conciliengeschichte, vol. II, pp. 905–911.

- Hefele, Conciliengeschichte, vol. II, pp. 911–927. (For an equitable appreciation of the conduct of Vigilius see, besides the article VIGILIUS, the judgment of Bois, in Diet. de theol. cath., II, 1238–39.)

- Herrin (1989) pp. 240–241

- Herrin (1989) p. 244

- Herrin (1989) p. 241 and the references therein

- Isidore of Seville, Chronica Maiora, no. 397a

- Herrin (1989) p. 241

- Price (2009) vol. I, p. 73–75

- "NPNF2–14. The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Excursus on the Genuineness of the Acts of the Fifth Council". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Straub, Johannes (1971), Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum. Tomus IV, volumen I, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter

- Price (2009)

- Kalamaras, Meletios (1985), The 5th Ecumenical Council [in Greek], Athens, Greece: Holy Diocese of Nicopolis

- Hefele, Conciliengeschichte, vol. II, pp. 855–858

- Price (2009) vol. 2, pp. 270-86.

- "NPNF2–14. The Seven Ecumenical Councils, The Definition of Faith". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Price (2009) vol. 2, pp. 270ff.

- Hubert Kaufhold (2012), "Sources of Canon Law in the Eastern Churches", in Wilfried Hartmann; Kenneth Pennington (eds.), The History of Byzantine and Eastern Canon Law to 1500, Catholic University of America Press, p. 223.

- "Perpetual Virginity: Dogmatic Status and Meaning : University of Dayton, Ohio". Archived from the original on 2021-04-19.

Bibliography

- Herrin, Judith (1989). The Formation of Christendom, revised, illustrated paperback edition. London: Princeton University Press and Fontana.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. Vol. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88-141056-3.

- Price, Richard (2009). The Acts of the Council of Constantinople of 553 – 2 Vol Set: With Related Texts on the Three Chapters Controversy. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 270–286. ISBN 978-1846311789.

- Hefele, Karl Josef von (2014) [The seven volumes of this work were first published between 1855 and 1874]. A History of the Councils of the Church: To the Close of the Council of Nicea, A.D. 325 (original, "Conciliengeschichte"). Vol. 2. Translated and edited by Edward Hayes Plumptre, Henry Nutcombe Oxenham, William Robinson Clark. Charleston, South Carolina: Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1293802021.