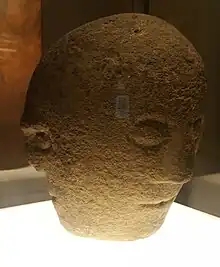

Corleck Head

The Corleck Head is an Irish carved stone idol usually dated to the 1st or 2nd century AD. It was found c. 1855 in either Corleck Hill or possibly in the nearby townland of Drumeague, County Cavan. The object is carved from a single block of local limestone and shows a three-faced (tricephalic) stone idol whose faces have enigmatic and haunted expressions, each having closely set eyes, a broad and rounded nose, and a simply drawn mouths.

| The Corleck Head | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Limestone |

| Size |

|

| Created | 1st or 2nd century AD |

| Discovered | c. 1855 Corkick hill, County Cavan, Ireland |

| Present location | National Museum of Ireland, Dublin |

| Identification | IA:1998:72[1] |

As with most stone artifacts from the European Iron Age, its origin, cultural significance and function are unknown. It probably represents a Celtic god and may have been part of a larger shrine associated with a Celtic head-cult.[2] The area where it was discovered had for millennia been a site of celebration of Lughnasadh, a three-day mid-autumn harvest festival. Its design seems influenced by contemporary Romano-British and northern European iconography. The three heads may represent a trinity representing the unity of the past, present and future, ancestral mother-figures representing "strength, power and fertility",[3] or an all-knowing, all-seeing god.

The Corleck Head was discovered during the excavation of a large Neolithic site between 1832 and 1900, but was not reported to archaeologists until 1948 after its prehistoric dating was realised by the historian Thomas Barron; until then it had been placed on top of a gatepost. Today it is on permanent display at the archaeology branch of the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. It was listed in the 2011 anthology A History of Ireland in 100 Objects.[3]

Discovery and provenance

In Irish, Corleck hill is known in Irish as Sliabh na Trí nDée or Sliabh na nDée Dána, both of which roughly translate as the "Hill of the Three Gods". Archaeological evidence indicates the hill was a site of pagan worship. It is traditionally associated with the Lughnasadh, an ancient Gaelic harvest festival.[4] Archaeologists believe it likely that the head was one of a series of objects placed at the site during the festival.[5] Corleck is one of six areas in Ulster where a cluster of presumably related stone idols have been found.[lower-alpha 1][6] Other cult objects found in the Corleck area include the wooden Ralaghan Idol (c. 1096–906 BC) and stone heads from nearby Corravilla and Corraghy.[7]

It was probably hidden at the same time as the Corraghy Head, a stone bust of a bearded man, now also in the National Museum of Ireland.[2][5] A number of early sources record that the Corleck Head was found alongside a now lost two-headed stone carving of a man with hair and a beard on one side, and a ram's head on the other.[8]

The Corleck head was discovered c. 1855 by the local farmer James Longmore Jr while searching for stones to build a house,[9] however the exact find spot is known.[10] It was probably Corleck hill, or less likely in a quarry on the nearby Drumeague Hill.[5][8][11]

After Longmore sold the farm to Sam Hall, the Corleck head was placed on the gatepost of a wall outside the farm house.[12] Emily Bryce, a relative of that family, remembered visits throwing stones at the head.[1] The head's age and significance were first recognised in 1935 by the local historian Thomas J. Barron. He contacted the National Museum of Ireland in 1937,[5] after which it was taken to Dublin for study by the archaeologist and museum's director Adolf Mahr, who secured funding to acquire it into the museum's collection.[1][13] Study of the object and its provenance preoccupied Barron until his death in 1992.[14]

Description

The Corleck head is a relatively large example of the type, being 33 cm (13 in) high and 22.5 cm (8.9 in) at its widest point.[5] The faces are all similar in form and expression, but not identical; according to the archeologist Eamonn Kelly, each seems to express a different mood.[15] They all have enigmatic expressions, built from very basic and simply described facial features, including a broad and flat wedge–shaped nose, bossed eyes that are closely-set but staring, and a thin, narrow, slit mouth.[16][3] One face is heavily browed. Another one, at the center of its mouth, has a small hole, a feature of several contemporary stone heads found in Yorkshire in England, Wales and Bohemia.[17][18]

The hole under the base suggests it was created for a pedestal which would have had a tenon (a joint connects two pieces of material).[7] This indicates that it probably was part of a larger pre–Christian shrine.[19][15]

Dating and function

The statue has not received significant scholarly study,[8] and dating single pieces of Iron-Age stone sculpture is extremely difficult given that they cannot be dated via techniques such as radiocarbon dating. In addition, the late-19th-century tendency to associate objects with mythical or a "Celtic Revival" viewpoint based on medieval texts or 19th-century romanticism, has been largely discredited.[20] Thus modern archaeologists date such objects based on their resemblance to other known examples in the contemporary Northern European context.[21] While the majority of the stone heads found in the Northern Irish counties since the 19th century are now believed to be pre-historic, others have since been identified as either from the Early Middle Ages or examples of 17th- or 18th-century folk art.[19]

Most known iconic (representational, as opposed to abstract) prehistoric Irish sculptures originate from the northern province of Ulster. They typically consist of a human head carved in the round in low relief. The majority are thought to have been produced between 300 BC and 100 AD.[22]

The Corleck Head probably represents a Celtic god, carved in a format derived from contemporary Romano-British iconography and symbolism.[15] Triple-head figures represented all-knowing and all-seeing gods who in Celtic religion symbolised the unity of, according to the historian Dáithí Ó Hogain, the "past, present and future".[23] According to the writer Miranda Aldhouse-Green, it may have been "used to gain knowledge of places or events far away in time and space".[24]

Idolatry

The head is one of the earliest known Irish anthropomorphic stone carvings, although it post-dates by around a millennium the c. 1000–500 BC Tandragee Idol found in County Armagh c. 1912.[19][25]

All of the faces in contemporary Irish examples have similar closely-set eyes, thin mouths and flat noses.[26] The hole at the Corleck's base indicates that it was once attached to a larger structure, perhaps a pillar comparable to the 6-foot wooden carving found in the 1790s in a bog near Aghadowey, County Londonderry, which is now lost but known from a very simple 19th-century drawing of an idol with four faces.[10]

Most surviving Irish Iron Age stone idols are cut from limestone blocks.[27] The Corleck Head is widely considered the finest example, in its simplicity of design and complexity of expression.[10][15] In 1972 the archaeologist and historian Etienn Rynne described it as "unlike all others in its elegance and economy of line."[7] Other local examples include a triple-head found before 1935 in Cortynan, County Armagh, an object found in Glejbjerg, Denmark, and two carved triple-heads from Greetland in England.[5][28]

.jpg.webp) The Ralaghan Idol, carved wood, c. 1096-906 BC[29]

The Ralaghan Idol, carved wood, c. 1096-906 BC[29].jpg.webp) The Tandragee Idol, c. 1000–500 BC

The Tandragee Idol, c. 1000–500 BC.jpg.webp) Stone idols, Boa Island, County Fermanagh, c. 400–800 AD. Left: the Lustymore idol, right: the Boa Island Janus.[30]

Stone idols, Boa Island, County Fermanagh, c. 400–800 AD. Left: the Lustymore idol, right: the Boa Island Janus.[30]

Notes

- The others are Cathedral Hill in Armagh town, the Newtownhamilton and Tynan areas in Armagh County, the most southern part of Lough Erne in County Fermanagh, and the Raphoe region in County Donegal.[6]

Citations

- Smyth (2012), p. 24

- "A Face From The Past: A possible Iron Age anthropomorphic stone carving from Trabolgan, Co. Cork". National Museum of Ireland. Retrieved 22 April 2023

- O'Toole, Fintan. "A history of Ireland in 100 objects: Corleck Head". The Irish Times, 25 June 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2022

- Smyth (2023), 5:30–13:44

- Kelly (2002), p. 142

- Rynne (1972), p. 78

- Rynne (1972), p. 84

- Waddell (1998), p. 371

- Smyth (2012), p. 25

- Waddell (1998), p. 360

- "Thomas J Barron: Biography". Library Service, Cavan County Council. Retrieved 4 February 2022

- Smyth (2023), 13:45–18:44

- Duffy (2012), pp. 150–153

- Smyth (2012), p. 88

- Kelly (2002), p. 132

- Ross (1958), p. 24

- Waddell (1998), pp. 360, 371

- Kelly (2002), pp. 132, 142

- Waddell (1998), p. 362

- Gleeson (2022), p. 20

- Morahan (1987–1988), p. 149

- Rynne (1972), p. 79

- Ó Hogain (2000), p. 23

- Aldhouse-Green (2015), "The Seeing Stone of Corleck"

- "The Tandragee Man—3000 year old statue". BBC, 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2022

- Rynne (1972), p. 80

- Rynne (1972), pp. 79–93

- Paterson (1962), p. 82

- Waddell (1998), p. 233

- Rynne (1972), plate IX

Sources

- Aldhouse-Green, Miranda. The Celtic Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends. London: Thames and Hudson, 2015. ISBN 978-0-5002-5209-3

- Armit, Ian. "Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe". Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-5218-7756-5

- Duffy, Patrick. "Reviewed Work: Landholding, Society and Settlement In Ireland: a historical geographer's perspective by T. Jones Hughes". Clogher Record, volume 21, No. 1 (2012). JSTOR 41917586

- Gleeson, Patrick. "Reframing the first millennium AD in Ireland: archaeology, history, landscape". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 2022

- Kelly, Eamonn. "The Iron Age". In Ó Floinn, Raghnall; Wallace, Patrick (eds). Treasures of the National Museum of Ireland: Irish Antiquities. Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7171-2829-7

- Kelly, Eamonn. "The Pagan Celts". Ireland Today, no. 1006, 1984

- Kelly, Eamonn. "Late Bronze Age and Iron Age Antiquities". In: Ryan, Micheal (ed). Treasures of Ireland: Irish Art 3000 BC – 1500 AD. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1983. ISBN 978-0-9017-1428-2

- Morahan, Leo. "A Stone Head from Killeen, Belcarra, Co. Mayo". Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society, volume 41, 1987–1988. JSTOR 25535584

- Ó Hogain, Dáithí. "Patronage & Devotion in Ancient Irish Religion". History Ireland, volume 8, no. 4, winter 2000. JSTOR 27724824

- Paterson, T.G.F. "Carved Head from Cortynan, Co. Armagh". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, volume 92, No. 1, 1962. JSTOR 25509461

- Raftery, Barry. Pagan Celtic Ireland: The Enigma of the Irish Iron Age. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994

- Ross, Anne. "The Human Head in Insular Pagan Celtic Religion". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, volume 91, 1958

- Rynne, Etienn. "Celtic Stone Idols in Ireland". In: Thomas, Charles. The Iron Age in the Irish Sea province: papers given at a C.B.A. conference held at Cardiff, January 3 to 5, 1969. London: Council for British Archaeology, 1972

- Rynne, Etienn. "The Three Stone Heads at Woodlands, near Raphoe, Co. Donegal". The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, volume 94, no. 2, 1964. JSTOR 25509564

- Smyth, Jonathan. "The Corleck Head and Other Aspects of East Cavan's Ancient Past". Cavan Library Service, 25 May 2023.

- Smyth, Jonathan. Gentleman and Scholar: Thomas James Barron, 1903 - 1992. Cumann Seanchais Bhreifne (Breifne Historical Society), 2012. ISBN 978-0-9534-9937-3

- Waddell, John. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Galway: Galway University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1-8698-5739-4

- Warner, Richard. "Two pagan idols - remarkable new discoveries". Archaeology Ireland, volume 17, no. 1, 2003

- Zachrisson, Torun. "The Enigmatic Stone Faces: Cult Images from the Iron Age?". In Semple, Sarah; Orsini, Celia; Mui, Sian (eds). Life on the Edge: Social, Political and Religious Frontiers in Early Medieval Europe. Hanover Museum, 2017. ISBN 978-3-9320-3077-2