Control self-assessment

Control self-assessment is a technique developed in 1987 that is used by a range of organisations including corporations, charities and government departments, to assess the effectiveness of their risk management and control processes.

| Part of a series on |

| Accounting |

|---|

|

A "control process" is a check or process performed to reduce or eliminate the risk of error. Since its introduction the technique has been widely adopted in the United States, European Union and other countries. There are a number of ways a control self-assessment can be implemented but its key feature is that, in contrast to a traditional audit, the tests and checks are made by staff whose normal day-to-day responsibilities are within the business unit being assessed.[1] A self-assessment, by identifying the higher risk processes within the organisation, allows internal auditors to plan their work more effectively.[2] A number of governmental organisations require the use of control self-assessment. In the United States it is a requirement of the FFIEC that control self-assessments are performed on IT systems and operational processes on a regular basis.[3] Benefits claimed for control self-assessment include creating a clear line of accountability for controls, reducing the risk of fraud and the creation of an organisation with a lower risk profile.[4][5]

In certain circumstances control self-assessment is not always effective. For example, it can be difficult to implement in a decentralised environment, in organisations where there is high employee turnover, where the organisation goes through frequent change or where the senior management of the organisation does not foster a culture of open communication.[6]

Development and worldwide adoption

Control self-assessment was developed by Gulf Canada in 1987 when the company's General Auditor, Bruce McCuaig was dissatisfied with the standard auditing techniques in use following the impact of the Watergate affair on the parent company, Gulf Oil Corporation. The decision to fully implement control self-assessment at Gulf Canada was driven by a number of factors. These included the presence of a consent decree requiring the company to report on its internal controls and the difficulties it was facing in estimating its oil and gas reserves using more traditional audit measures.[7]

Over the next ten years Gulf Canada developed a framework to support the analysis and evaluation of control processes by operational staff. This included anonymous voting to ensure there was no impediment to staff expressing their views. The approach was first published in Internal Auditor in December 1990.[8] Gulf Canada discontinued this facilitated meeting approach in 1997 although it continued with control self-assessment using different techniques.[7]

Following Gulf Canada's introduction of control self-assessment many private sector organisations implemented similar techniques. In the United States several states made reviews based on control self-assessment practices mandatory as did the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation.[7]

Initially external auditors ignored the benefits of control self-assessment even though it was effective at providing audit evidence around the "soft" areas (such as staff morale) that are critical to the effectiveness of internal control systems.[9]

After a number of financial scandals, notably the collapse of Robert Maxwell's publishing empire, the United Kingdom government commissioned Adrian Cadbury to chair an investigation into corporate governance. The committee published its report The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance in 1992. In section 4, Reporting and Controls, Cadbury made a number of recommendations that led to the increased adoption of control self-assessment in the UK. In particular section 4.5 of the Code of Practice contained within the report required that the directors of a company should report on the effectiveness of the company's system of internal control in each annual report.[10]

In March 2000 the European Commission approved a white paper on reform that led to a major change in the way the Commission was managed. These changes included recommendations for each department to establish an effective internal control system. To support the implementation of the internal controls the Directorate-General for Budget's Central Financial Service developed a control self-assessment process. This first control self-assessment identified several areas for improvement in internal control across the Commission most notably the need to implement a more systematic approach to risk management. The outcome of this first self-assessment was the implementation of the requirement for every Directorate General to perform a control and risk self-assessment annually.[11]

In 2007 the United States implemented the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. In order to comply with section 404 of the Act the company had to perform a top down risk assessment which necessitated the production of an "internal control report" that affirmed "the responsibility of management for establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting." . This report has to include an evaluation of the effectiveness of the internal controls and procedures that are related to financial reporting. To meet this requirement organisations increasingly began to perform a control self-assessment using a recognised standard methodology. The organisation's external auditors, who are required to sign-off the internal control report, typically became more deeply involved in the control self-assessment process as it facilitated their later review of the internal control report.[12]

In the United Kingdom in 2011 the Financial Services Authority recognised in its recommendations for the improvement of operational risk management that the assessment of risks through a control self-assessment may be an important means of identifying risks. It also noted that for the assessment to be fully effective it had to be fully integrated into the financial organisation's risk-management process.[13]

Performing the control self-assessment

The first step in control self-assessment is to document the organisation's control processes with the aim of identifying suitable ways of measuring or testing each control. The actual testing of the controls is performed by staff whose day-to-day role is within the area of the organisation that is being examined as they have the greatest knowledge of how the processes operate.[1][4] The two common techniques for performing the evaluations are:

- Workshops, that may be but do not have to be independently facilitated, involving some or all staff from the business unit being tested;

- Surveys or questionnaires completed independently by the staff.

Both approaches are the opposite of formal audits where the auditors, not the business unit staff, will perform the assessment.[1]

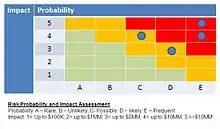

On completion of the assessment each control may be rated based on the responses received to determine the probability of its failure and the impact if a failure occurred. These ratings can be mapped to produce a heatmap showing potential areas of vulnerability.

Methodologies

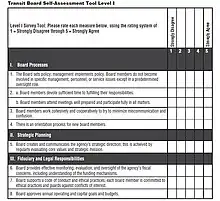

Six basic methodologies for control self-assessment have been defined:[14]

- Internal Control Questionnaire (ICQ) self-audit

- Customised questionnaires

- Control guides

- Interview techniques

- Control model workshops

- Interactive workshops

The National Institute of Standards and Technology control self-assessment methodology is based on customised questionnaires. It is an IT focused methodology suitable for assessing system based controls. It provides a cost-effective technique to determine the status of information security controls, identify any weaknesses and, where necessary, define an improvement plan.[15] The methodology uses a questionnaire that contains specific control objectives and techniques against a system or group of systems can be tested and measured. The methodology was designed for United States federal agencies but can also be valuable for private sector organisations.[15]

The COBIT methodology can be used for control self-assessment; like the NIST methodology it was designed for IT focused assessments. COBIT's Process Description component provides a reference model of an organisation's processes and their ownership. Its Control Objectives component provides a set of requirements considered necessary for effective control of each IT process with the organisation. Assessment and evaluation of these components using the Management Guidelines component provides an assessment mechanism that generates a maturity model indicating if the organisation is meeting its control objectives.[14]

The Institute of Internal Auditors based its control self-assessment methodology on the Total Quality Management approaches of the 1990s as well as the COSO's framework. The methodology became part of the International Standards for Professional Practice of Internal Auditing and was adopted by a large number of major organisations.[16]

A number of other methodologies to standardise the control self-assessment have been published.[17][18] The Institute of Internal Auditors offers a certification in control self-assessment practice.[19]

Software tools

A number of software packages are available to support the control self-assessment process. These are typically modified versions of software developed originally for internal use by audit and accountancy firms such as Deloitte or by niche vendors specialising in business or financial management tools.

Benefits

Control self-assessment creates a clear line of accountability for controls, reduces the risk of fraud (by examining data that may flag unusual patterns of transactions) and results in an organisation with a lower risk profile.[4][5]

A number of other soft benefits have been claimed for organisations performing control self-assessment. These include a better understanding of business operations (by both management and operational staff); stronger awareness of risk practices; a reinforced corporate governance regime and internal audit efficiency improvements.[4][20]

Criticism

Some researchers have criticised control self-assessment as a flawed approach as the way risk is defined and measured is unsophisticated. In particular, control self-assessment may understate risk by not identifying extreme downside risk. An extreme downside risk is a highly improbable event that would have catastrophic consequences if it occurred. These risks should have a high overall risk score (generally calculated as a product of the probability of a risk occurring and the impact if it does occur on a scale of 1 to 5). Individuals performing the control self-assessment are consequently unable to significantly differentiate between risks leading to extreme low probability risks either being excluded from the analysis or grouped together with other more probable (but still unlikely) risks that have a less severe impact.[21]

The continual focus on risk elimination that a control self-assessment can lead to has also been criticised. The process of continual evaluation of risks and making plans to mitigate and eliminate them may lead to an unbalanced corporate culture where risks are eliminated ignoring the risk-return ratio of different business choices.[21]

See also

External links

References

- Gilbert W. Joseph; Terry J. Engle (December 2005). "The Use of Control Self-Assessment by Independent Auditors". The CPA Journal. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- "Control Self-assessment: An Introduction". The Institute of Internal Auditors. Archived from the original on 2010-08-23. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- "FFIEC IT Examination Handbook". FFIEC. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- McNally, J.Stephen (12 November 2007). "Control self-assessment:Everybody pitching in with internal controls". accountingweb.

- Spencer Pickett, K.H. & Pickett, Jennifer M. (2010). The Internal Auditing Handbook (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. p. 585.

- "Control Self-Assessment:The Future of Store Audits in Retail Stores" (PDF). Protivit Incorporated. 2006. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- Professional Practice Pamphlet 98-2 A Perspective on Control Self-Assessment (PDF). Florida: The Institute of Internal Auditors. 1998. ISBN 089413406X. Retrieved 2012-03-31.

- K.H. Spencer Pickett (2011). The Essential Guide to Internal Auditing (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons Limited. p. 81.

- Joseph, Gilbert W (1 August 2001). "Use of control self-assessment in audits". The CPA Journal. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (PDF) (Report). 1 December 1992. ISBN 0852589131. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- Central Financial Service, European Commission (18 March 2002). "2nd Quality Conference for Public Administration in the EU: Note for the File". Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- Engel, Terry J.; Joseph, Gilbert W. (2007). "Improving Internal and External Audit Coordination". 11 (2). CSA Sentinel. The Institute of Internal Auditors. Archived from the original on 2014-03-20. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Enhancing frameworks in the standardised approach to operational risk – Guidance note" (PDF). Financial Services Authority. January 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- Sunil Bakshi (2004). "Control Self-assessment for Information and Related Technology". Journal of the Information Systems Audit and Control Association. 1: 4.

- Marianne Swanson. "Security Self-assessment Guide for Information Technology Systems". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2012-04-04.

- Robert Moeller (2009). Brink's Modern Internal Auditing: A Common Body of Knowledge. John Wiley & Sons Inc., Canada.

- Álvarez, Gene (2004). Operational Risk: Practical Approaches to Implementation.

- Gene Álvarez; Phil Gledhill (24 November 2010). "A comprehensive risk and control self-assessment methodology". Risk.net. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- "Certification in Control Self Assessment (CCSA)". Institute of Internal Auditors. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- "Control Self Assessment". PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- Lee, Judy; Wee, Lieng-Seng (28 September 2005). "Companies Using Control Self Assessment Don't Really Know their Risk" (PDF). Dragonfly. Retrieved 2012-03-14.