Philosophy of color

The philosophy of color is a subset of the philosophy of perception that is concerned with the nature of the perceptual experience of color. Any explicit account of color perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views, distinguishing namely between externalism/internalism, which relate respectively to color realism, the view that colors are physical properties that objects possess, and color fictionalism, the view that colors possess no such physical properties.[1]

History

Philosophical concerns about the nature of color can be traced back at least as far as Anaxagoras (5th century BCE), who favoured color realism in his sophism: "Snow is frozen water. But water is dark in color. Therefore, snow is dark in color." Anaxagoras claimed that our perception deviated from the truth "...owing to the feebleness [of the senses]."[2] Later, Democritus (circa 400 BCE) would say, "By convention sweet, by convention bitter, by convention hot, by convention cold, by convention color; but by verity atoms and void." In direct refutation of Anaxagoras, the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus (circa 160 CE) noted that different animals would have different perceptions of color due to differences in their eyes, and that color was an attribute of a subject, and not the object itself.[3]

Theories of color

One of the topics in the philosophy of color is the problem of the ontology of color. The questions comprising this field of research are, for example, what kind of properties colors are (i.e. are they physical properties of objects? Or are they properties of their own kind?), but also problems about the representation of colors, and the relationship between the representation of colors and their ontological constitution.[4]

Within the ontology of color, there are various competing types of theories. One way of posing their relationship is in terms of whether they posit colors as sui generis properties (properties of a special kind that can't be reduced to more basic properties or constellations of such). This divides color primitivism from color reductionism. A primitivism about color is any theory that explains colors as irreducible properties. A reductionism is the opposite view, that colors are identical to or reducible to other properties. Typically a reductionist view of color explains colors as an object's disposition to cause certain effects in perceivers or the very dispositional power itself (this sort of view is often dubbed "relationalism", since it defines colors in terms of effects on perceivers, but it also often called simply dispositionalism – various forms of course exist). An example of a notable theorist that defends this kind of view is the philosopher Jonathan Cohen.

Another type of reductionism is color physicalism. Physicalism is the view that colors are identical to certain physical properties of objects. Most commonly the relevant properties are taken to be reflectance properties of surfaces (though there are accounts of colors apart from surface colors too). Byrne, Hilbert and Kalderon defends versions of this view. They identify colors with reflectance types.

A reflectance type is a set, or type, of reflectances, and a reflectance is a surface's disposition to reflect certain percentages of light specified for each wavelength within the visible spectrum.

Both relationalism and physicalism of these kinds are so called realist theories, since apart from specifying what colors are, they maintain that colored things exist.

Primitivism may be either realist or antirealist, since primitivism simply claims that colors aren't reducible to anything else. Some primitivists further accept that, though colors are primitive properties, no real or nomologically possible objects have them. Insofar as we visually represent things as colored – on this view – we are victims of color illusions. For this reason primitivism that denies that colors are ever instantiated is called an error theory.

Color discourse

If color fictionalism is true, and the world has no colors, should one just stop color discourse, and all the time wear clothes that clash with each other? Prescriptive color fictionalism would say no. In prescriptive color fictionalism, while color discourse is, strictly speaking, false, one should continue using it in everyday life as though color properties do exist.

Color vision became an important part of contemporary analytic philosophy due to the claim by scientists like Leo Hurvich that the physical and neurological aspects of color vision had become completely understood by empirical psychologists in the 1980s. An important work on the subject was C. L. Hardin's 'Color for Philosophers,' which explained stunning empirical findings by empirical psychologists to the conclusion that colors cannot possibly be part of the physical world, but are instead purely mental features.

David Hilbert and Alexander Byrne have devoted their careers to philosophical issues regarding color vision. Byrne and Hilbert have taken a minority position that colors are part of the physical world. Nigel J.T. Thomas provides a particularly clear presentation of the argument. The psychologist George Boeree, in the tradition of J. J. Gibson, specifically assigns color to light, and extends the idea of color realism to all sensory experience, an approach he refers to as "quality realism".

Jonathan Cohen (of UCSD) and Michael Tye (of UT Austin) have also written many essays on color vision. Cohen argues for the uncontroversial position of color relationalism with respect to semantics of color vision in Relationalist Manifesto. In The Red and the Real, Cohen argues for the position, with respect to color ontology that generalizes from his semantics to his metaphysics. Cohen's work marks the end of a vigorous debate on the topic of color that started with Hardin.

Michael Tye argues, among other things, that there is only one correct way to see colors. Therefore, the colorblind and most mammals do not really have color vision because their vision differs from the vision of "normal" humans. Similarly, creatures with more advanced color vision, although better able to distinguish objects than people, are suffering from color illusions because their vision differs from humans. Tye advanced this particular position in an essay called True Blue.

Paul Churchland (of UCSD) has also commented extensively on the implication of color vision science on his version of reductive materialism. In the 1980s Paul Churchland's view located colors in the retina. But his more recent view locates color in spectral opponency cells deeper in the color information stream. Paul Churchland's view is similar to Byrne and Hilbert's view, but differs in that it emphasized the subjective nature of color vision and identifies subjective colors with coding vectors in neural networks.

Many philosophers follow empirical psychologists in endorsing color irrealism, the view that colors are entirely mental constructs and not physical features of the world. Surprisingly, most philosophers who have extensively addressed the topic have attempted to defend color realism against the empirical psychologists who universally defend color antirealism.

Jonathan Cohen has edited a collection of essays on the topic of color philosophy called Color Vision and Color Science, Color Ontology and Color Science.

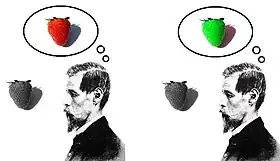

Inverted spectrum

The inverted spectrum is a thought experiment dating back to John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.[5] It uses color to discuss the nature of qualia. As explained by Locke:

Neither would it carry any Imputation of Falsehood to our simple Ideas, if by the different Structure of our Organs, it were so ordered, That the same Object should produce in several Men’s Minds different Ideas at the same time; v.g. if the Idea, that a Violet produced in one Man’s Mind by his Eyes, were the same that a Marigold produces in another Man’s, and vice versâ. For since this could never be known: because one Man’s Mind could not pass into another Man’s Body, to perceive, what Appearances were produced by those Organs; neither the Ideas hereby, nor the Names, would be at all confounded, or any Falshood be in either. For all Things, that had the Texture of a Violet, producing constantly the Idea, which he called Blue, and those which had the Texture of a Marigold, producing constantly the Idea, which he as constantly called Yellow, whatever those Appearances were in his Mind; he would be able as regularly to distinguish Things for his Use by those Appearances, and understand, and signify those distinctions, marked by the Names Blue and Yellow, as if the Appearances, or Ideas in his Mind, received from those two Flowers, were exactly the same, with the Ideas in other Men’s Minds.[5]

Color fictionalists argue that, since we can imagine perceiving an inverted color spectrum, it must follow that color represents a property that determines the way things look to us, yet has no physical basis.

Mary's room

Mary's room is a thought experiment underpinning the knowledge argument. It was an argument to counter color realism and more broadly physicalism. The thought experiment was originally proposed by Frank Jackson as follows:

Mary is a brilliant scientist who is, for whatever reason, forced to investigate the world from a black and white room via a black and white television monitor. She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires, let us suppose, all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes, or the sky, and use terms like "red", "blue", and so on. She discovers, for example, just which wavelength combinations from the sky stimulate the retina, and exactly how this produces via the central nervous system the contraction of the vocal cords and expulsion of air from the lungs that results in the uttering of the sentence "The sky is blue". ... What will happen when Mary is released from her black and white room or is given a color television monitor? Will she learn anything or not?[6]

See also

Notes

- "Colour Fictionalism – SFU" (PDF). sfu.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Curd, Patricia (2019). "Anaxagoras". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Empiricus, Sextus. Outlines of Pyrronism (PDF).

- Maund, Barry (23 March 2018). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 23 March 2018 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Locke, John (1689). An essay concerning human understanding. Oxford.

- Jackson, Frank (1982). "Epiphenomenal Qualia". Philosophical Quarterly. 32 (127): 127–136. doi:10.2307/2960077. JSTOR 2960077.

References

- Maund, Barry (1 December 1997). "Color". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Byrne, Alex; Hilbert, David R. (2003). "Color realism and color science" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 26 (1): 3–64. doi:10.1017/S0140525X03000013. hdl:1721.1/50993. PMID 14598439. S2CID 45066819.

- Thomas, Nigel J. T. (2001). "Color realism: Toward a solution to the "hard problem"". Consciousness and Cognition. 10 (1): 140–145. doi:10.1006/ccog.2000.0484. PMID 11273636. S2CID 6593866. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Eklund, Matti (30 March 2007). "Fictionalism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Kalderon, Mark Eli (2005). Fictionalism in Metaphysics. Clarendon. ISBN 978-0-19-928219-7.

- Gatzia, Dimitria Electra (2010). "Colour Fictionalism" (PDF). Rivista di Estetica. 1 (43): 109–123. doi:10.4000/estetica.1795.

- Boeree, C. George (2002). "Quality Realism". Shippensburg University. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Further reading

- Hardin, C. L. (1988). Color for Philosophers: Unweaving the Rainbow. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0872200401.