Colchester Castle

Colchester Castle is a Norman castle in Colchester, Essex, England, dating from the second half of the eleventh century. The keep of the castle is mostly intact and is the largest example of its kind anywhere in Europe, due to its being built on the foundations of the Roman Temple of Claudius, Colchester. The castle endured a three-month siege in 1216, but had fallen into disrepair by the seventeenth century when the curtain walls and some of the keep's upper parts were demolished; its original height is debated. The remaining structure was used as a prison and was partially restored as a large garden pavilion, but was purchased by Colchester Borough Council in 1922. The castle has since 1860 housed Colchester Museum, which has an important collection of Roman exhibits. It is a scheduled monument[1] and a Grade I listed building.[2]

| Colchester Castle | |

|---|---|

| Colchester, Essex, England | |

Colchester Castle keep from the south, showing the main entrance | |

Colchester Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.890589°N 0.903047°E |

| Type | Norman castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Borough of Colchester |

| Controlled by | Colchester & Ipswich Museums |

| Condition | Keep is largely intact. |

| Site history | |

| Built | circa 1076 |

| Built by | William I of England |

| Demolished | Bailey wall and keep battlements, 17th century |

| Events | 1216 siege in the First Barons' War 1648 capture in the Siege of Colchester |

Construction

The attribution of the castle as a royal foundation is based on a charter of Henry I dated 1101, granting the town and castle of Colchester to Eudo Dapifer "as my father had them and my brother and myself", Henry's father and brother being William I, "William the Conqueror", and William II, "William Rufus".[3] The somewhat unreliable Colchester Chronicle, written in the late 13th century, credits Eudo with the construction of the castle and gives a commencement date of 1076. The design of the castle has been associated with Gundulf of Rochester purely on the basis of the similarities between Colchester and the White Tower at the Tower of London; however, both keeps also resemble the much earlier example at Château d'Ivry-la-Bataille in Upper Normandy.[4]

Construction of the keep

At one and a half times the size of the ground plan of the White Tower,[5] Colchester's keep of 152 by 112 feet (46 m × 34 m) has the largest area of any medieval tower built in Britain or in Europe.[6][7][8] The enormous size of the keep was dictated by the decision to use the masonry base or podium of the Temple of Claudius, built between AD 49 and 60, which was the largest Roman temple in Britain. The site is on high ground at the western end of the walled town and at the time of the Norman Conquest, a Saxon chapel and other buildings which may have constituted a royal vill lay close by the ruins of the temple. The obvious motive for reusing this site was the ready made foundations and the availability of Roman building materials in an area without any naturally occurring stone.[9] Another factor may have been that the Normans like to see themselves as imperial successors to the Romans, William being frequently compared by his biographer, William of Poitiers, to Julius Caesar and his barons to the Roman Senate.[10] The Colchester Chronicle described the temple site as a palace built by the mythical Roman-era King Coel; either way, it was providing a provenance for the Norman occupiers as the inheritors of a heroic past.[9] Siting the castle so close to the centre of the town makes Colchester the exception to the rule that Norman castles were built as a part of the town's external defences, with access to open countryside.[11]

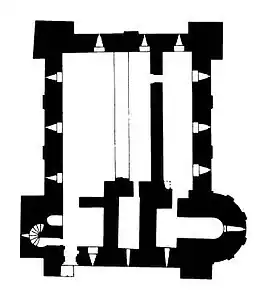

The initial preparation of the site involved the demolition of surviving superstructure of the Roman temple, resulting in a layer of mortar rubble at the Norman ground level. The walls of the keep sit on narrow foundation trenches filled with rubble and mortar, and directly abut the edge of the Roman podium, except in the south where they are set back to avoid the original temple steps and to facilitate the digging of a well. The walls are made of coursed rubble, including septaria and Roman brick robbed from nearby ruins. Ashlar dressings are of Barnack and other stone, as well as Roman tile and brick.[4] A large apse projects from the south-east corner, resembling St John's Chapel in the White Tower but there is no firm evidence that a similar chapel ever existed at Colchester.[12] It has been speculated that an apse was added to the Temple of Claudius in the 4th century during a putative conversion to a Christian church and that the Normans followed this outline.[13] The keep was divided internally by a wall running from north to south; a second dividing wall was added to the larger eastern section at a later date.[14]

Initially, the keep was only built to the height of the first floor; remnants of the crenellations which surmounted this first phase can still be seen in the exterior walls. It seems likely that either a financial or military crisis dictated that the partly completed keep had to be made defensible. A Danish raid in support of the Revolt of the Earls in 1075 or the threatened invasion by Canute IV in 1085 have both have been suggested as possible causes. Another theory is that only a single-story structure was originally intended.[15] The keep today has only two storeys; the original height is unknown because of demolition work carried out in the late 17th century. In 1882, J. Horace Round proposed that, like the White Tower, Colchester would have had four storeys, with a double-height great hall and chapel. This view was widely accepted throughout most of the 20th century. More recently, researchers have supported a three-storey model and some of the latest work suggests that there may have only ever been two storeys.[16]

This is based on pre-demolition depictions of the castle, which despite errors and inconsistencies, all show the squat profile evident today rather than an immensely tall three- or four-storey tower, also the short time frame in which demolition can have occurred, and finally analysis of various surviving internal details which suggest that, unlike the White Tower, the great hall was on the first floor.[16] Further uncertainty surrounds the position of the original entrance; the current main doorway in the southwestern tower dates from the second phase of construction which saw the addition of the first floor and staircases. Architectural features suggest that this second phase was undertaken after about 1100, probably by Eudo following the charter of 1101.[17] In the mid-13th century, a masonry barbican was built adjacent to the south-west tower to protect the main doorway,[18] replacing an earlier forebuilding.[14]

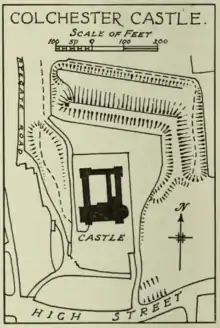

Construction of the bailey

The defences of the bailey consisted principally of a large earthen rampart and ditch surrounding the keep, the northern section of which survives but was heavily landscaped in the 19th century. Archaeological evidence has found that these embankments were thrown up over the remains of the Roman wall of the temple precinct and on the northern side were probably constructed at the same time as the first phase of the keep. The rampart to the north-east was 28.5 metres (94 ft) wide by 4 metres (13 ft) high.[19] The southern embankment seems to have been completed during the second phase of keep construction around 1100.[20] Inside the bailey, a late Anglo-Saxon chapel stood close to the southern edge of the keep and a domestic hall to the southeast of, and aligned with the chapel, were both retained during the first phase of keep construction.[19]

The chapel was rebuilt during the second phase and the hall had a large fireplace added at around the same time.[21] A weak lower or "nether" bailey was formed by two less substantial bank-and-ditch barriers which extended northwards as far as the town walls. This may be the "new bailey" mentioned in 1173, or perhaps the masonry walls of the main or "upper" bailey which were in place by 1182. No trace of the stone walls has been found, which suggests that were located at the top of the rampart. A twin-towered gatehouse gave access to the bailey in its southwest corner, probably built at the same time as the bailey walls,[22] although there is no mention of it until the 1240s; it was approached by a bridge over the ditch. A palisade, presumably part of the nether bailey defences, blew down in 1218 and again in 1237, and further repairs to it were needed in 1275–76.[14]

Later history

Medieval

Control of Colchester Castle reverted to the crown following the death of Eudo in 1120 and thereafter, the castle was governed by crown-appointed constables, or was in the care of the High Sheriff of Essex when no-one had that role. In 1190, the acquisition of 26 military tunics for the castle are evidence of a permanent garrison.[14] Kings Henry I, Henry II and Henry III are all known to have visited the castle.

In 1214, the hereditary constable was William de Lanvalai, who was one of the barons opposed to King John. In November of that year, John arrived at Colchester, probably in an unsuccessful attempt to win over Lanvalai, who shortly afterwards left the castle in the care of the sheriff and joined the other rebel barons at Bury St Edmunds. Meanwhile, John sent a replacement constable to Colchester, Stephen Harengood, who was probably a Flemish mercenary, with orders to improve the castle's defences. The barons later marched on London, forcing John to accept the Magna Carta at Runnymede in June 1215, which included a provision that Colchester be returned to Lanvalai. Within months, John had refused to be bound by the terms of the charter and the First Barons' War broke out.[23]

John besieged Rochester Castle before sending an army towards Colchester, under the command of a French mercenary called Savary de Meuleon. In the meantime, the barons had appealed for help to King Louis VIII of France and accordingly, a French contingent had arrived to garrison Colchester Castle for the barons. The siege began in January 1216 and ended in March when King John himself arrived; the French garrison of 116 men were able to negotiate a safe passage to London. although that didn't prevent them from being arrested there.[23] Following the capture of Colchester, Harengood was reinstated as constable and made sheriff, but in 1217, the castle was handed-over to the French and the barons as part of a truce agreement. However, it was recovered by the boy king Henry III in the Treaty of Lambeth in September 1217 which finally ended the war, and William of Sainte-Mère-Église, the Bishop of London, was made constable.[14]

17th and 18th centuries

In 1607 custody of the castle was granted for life to Charles, Baron Stanhope of Harrington (1593–1675). In 1624 Stanhope granted the lease to Thomas Holmes, gentleman and maltster, the father of John Holmes, who emigrated to Plymouth Colony and became Messenger of the Court there.[24] Custody of the castle, the bailey, and King's Meadow north of the river Colne remained in the Holmes family until after 1659.[25] In 1629 Charles I alienated the reversion of the castle to James Hay, Earl of Carlisle, which passed in 1636 to Archibald Hay. In 1649 Hay sold his interest to Sir John Lenthall, while in 1650 a Parliament Survey condemned the building and valued the stone at five pounds.[26] In 1656 Lenthall sold his interest to Sir James Norfolk or Northfolk, who finally bought out Stanhope's interest in 1662.[14] In 1683 an ironmonger, John Wheely, was licensed to pull it all down - presumably to use as building material in the town. After "great devastations" in which much of the upper structure was demolished using screws and gunpowder, he gave up when the operation became unprofitable.[27]

The castle has had various uses since it ceased to be a royal castle. It has been a county prison, where in 1645 the self-styled Witchfinder General, Matthew Hopkins interrogated and imprisoned suspected witches. In 1648, during the Second English Civil War, the Royalist leaders Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle were executed just to the rear of the castle. Local legend has it that grass will not grow on the spot on which they fell. A small obelisk now marks the point. In 1656 the Quaker James Parnell was martyred there.

In 1705 Wheely sold the castle to Sir Isaac Rebow, who left it to his grandson Charles Chamberlain Rebow in 1726.[28] In 1727 the castle was bought by Mary Webster for her daughter Sarah, who was married to Charles Gray, the Member of Parliament for Colchester. To begin with, Gray leased the keep to a local grain merchant and the east side was leased to the county as a gaol. In the late 1740s Gray restored parts of the building, in particular the south front. He created a private park around the ruin and his summer house (perched on the old Norman castle earthworks, in the shape of a Roman temple) can still be seen. He also added a library with large windows and a cupola on the south-east tower, which was completed in 1760. On Gray's death in 1782, the castle passed to his step-grandson, James Round, who continued the restoration work.

19th and 20th centuries

The part of the castle under the chapel remained in use as a gaol, which was enlarged in 1801. A long-serving gaoler called John Smith lived on site with his family. His daughter Mary Ann Smith was born there in 1777 and lived her whole life in the castle, becoming the librarian until her death in 1852. She is believed to have planted the sycamore tree which is still growing on top of the southwest tower, either to celebrate the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 or to mark her father's death in the same year.

Between 1920 and 1922, the Castle and the associated parkland were bought by the Borough of Colchester using a large donation from Weetman Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray, a wealthy industrialist who had been the town's Member of Parliament. The Park is split into the Upper and Lower Castle Parks. A museum of artefacts owned by the borough had been on display at the castle since 1860, and the roofing over of the keep in the mid-1930s allowed for a considerable expansion.[29] Between January 2013 and May 2014 the castle museum underwent extensive refurbishment costing £4.2 million. The programme of work improved and updated the displays with the latest research into the castle's history, and supported the repair of the roof.[30]

Ownership

The later inheritance of the castle and its grounds is illustrated below. Only those greyed out did not at some time own the building. Though Charles Gray Round died before the area was sold to the corporation of Colchester, his will ensured that it was held in trust with that eventual purpose.

| Mary Webster | John Webster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ralph Creffeild (1) | Sarah Webster | Charles Gray (2) | Mary Wilbraham | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peter Creffeild | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thamer Creffeild | James Round | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| James Round | Charles Round | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Charles Gray Round | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- "Colchester Castle and the Temple of Claudius, Non Civil Parish - 1002217 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- "THE CASTLE KEEP (INCLUDING EXCAVATED REMAINS OF FOREBUILDING IN MOAT), Non Civil Parish - 1123674 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- Goodall 2011, p. 79.

- Radford 2013, p. 371.

- Creighton 2002, p. 150.

- Hull 2006, p. 101.

- Friar 2003, p. 16.

- MS 2011, History.

- Radford 2013, p. 369.

- Morris 2012, p. 54.

- Radford 2013, p. 380.

- Crummy 1994, p. 6.

- Crummy 1994, p. 4.

- Cooper 1994, pp. 241–248.

- Radford 2013, p. 370.

- Davies 2016, pp. 3–20.

- Radford 2013, pp. 371, 374.

- Radford 2013, pp. 378–379.

- Radford 2013, p. 373.

- Radford 2013, pp. 377–378.

- Radford 2013, p. 375.

- Radford 2013, p. 379.

- Phillips 2017.

- J. Horace, Round (1889). "Some Documents Relating to Colchester Castle". Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society. Series 2. III: 143–154.

- "Assignment of rest of 21 yr. lease by Tobias Weaton, turner, of Colchester, Amos Woodward, carpenter, of Colchester, and Thos. Holmes, maltster, of Colchester (Executors of Susan Morton, widow, of Colchester) to Jn. Rayner, senr., merchant, of Colchester". The National Archives.

- "Extract from Parliamentary Surveys, 1650 (ERO T/P 64/24)". Essex Records Office.

- Wheeler 1920, p. 87.

- Baggs et al. 1994.

- "Colchester Castle Redevelopment - History". www.cimuseums.org.uk. Colchester & Ipswich Museums. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Burton 2012, p. 17.

References

- Baggs, A P; Board, Beryl; Crummy, Philip; Dove, Claude; Durgan, Shirley; Goose, N R; Pugh, R B; Studd, Pamela; Thornton, CC (1994). "Castle". In Cooper, Janet; Elrington, C R (eds.). A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9, the Borough of Colchester. London: Victoria County History. pp. 241–248.

- Burton, Peter A., ed. (2012). "Colchester Castle" (PDF). The Castle Studies Group Bulletin. 14. ISSN 1741-8828. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Cooper, Janet; Elrington, C. R., eds. (1994). A History of the County of Essex: The Borough of Colchester. Vol. IX. London: Victoria County History. pp. 241–248. ISBN 978-0-19-722784-8. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Creighton, Oliver (2002). Castles and Landscapes. Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-5896-3.

- Crummy, Philip (1994). A Survey of Colchester Castle (PDF) (Report). The Colchester Archaeological Trust. ISSN 0952-0988. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Davies, John A; Riley, Angela; Levesque, Jean-Marie, eds. (2016). "IV". Castles and the Anglo-Norman World. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-78570-022-4. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2.

- Goodall, John (2011). The English Castle: 1066–1650. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11058-6. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Hull, Lise (2006). Britain's Medieval Castles (illus. ed.). Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-275-98414-4. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Morris, Marc (2012). Castle: A History of the Buildings that Shaped Medieval Britain. Windmill Books. ISBN 978-0-09-955849-1.

- "Colchester Castle Museum: History". Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service and Colchester Borough Council. 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Phillips, Andrew (2017) [2004]. "IV". Colchester: A History. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0750987509. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Radford, David; Gascoyne, Adrian; Wise, Philip, eds. (2013). Colchester, Fortress of the War God: An Archaeological Assessment. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-508-8. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Wheeler, R. E. M. (1920). "The Vaults under Colchester Castle: A Further Note". The Journal of Roman Studies. X: 87–89. doi:10.2307/295791. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 295791. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

Further reading

- Crummy, Philip (1981). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon and Norman Colchester (PDF). Published by the Colchester Archaeological Trust and the Council for British Archaeology. ISBN 0-906780-06-3.

- Appendix 4 Notes on Colchester Keep (PDF) This section includes a plan of the keep.

- Appendix 5 Notes on the borough seals (PDF) Borough seals include mediaeval representations of the castle.

- Wheeler, R. E. Mortimer; Laver, Philip G. (1919), "Roman Colchester", Journal of Roman Studies, IX: 139–169, doi:10.2307/296003, JSTOR 296003