Glomerular filtration rate

Renal functions include maintaining an acid–base balance; regulating fluid balance; regulating sodium, potassium, and other electrolytes; clearing toxins; absorption of glucose, amino acids, and other small molecules; regulation of blood pressure; production of various hormones, such as erythropoietin; and activation of vitamin D.

One of the measures of kidney function is the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Glomerular filtration rate describes the flow rate of filtered fluid through the kidney. The creatinine clearance rate (CCr or CrCl) is the volume of blood plasma that is cleared of creatinine per unit time and is a useful measure for approximating the GFR. Creatinine clearance exceeds GFR due to creatinine secretion,[1] which can be blocked by cimetidine. Both GFR and CCr may be accurately calculated by comparative measurements of substances in the blood and urine, or estimated by formulas using just a blood test result (eGFR and eCCr) The results of these tests are used to assess the excretory function of the kidneys. Staging of chronic kidney disease is based on categories of GFR as well as albuminuria and cause of kidney disease.[2]

The normal range of GFR, adjusted for body surface area, is 100–130 average 125 mL/min/1.73m2 in men and 90–120 mL/min/1.73m2 in women younger than the age of 40. In children, GFR measured by inulin clearance is 110 mL/min/1.73 m2 until 2 years of age in both sexes, and then it progressively decreases. After age 40, GFR decreases progressively with age, by 0.4–1.2 mL/min per year.

Estimated GFR (eGFR) is now recommended by clinical practice guidelines and regulatory agencies for routine evaluation of GFR whereas measured GFR (mGFR) is recommended as a confirmatory test when more accurate assessment is required.[3]

Definition

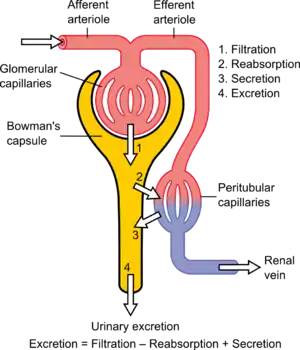

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is the volume of fluid filtered from the renal (kidney) glomerular capillaries into the Bowman's capsule per unit time.[4] Central to the physiologic maintenance of GFR is the differential basal tone of the afferent (input) and efferent (output) arterioles (see diagram). In other words, the filtration rate is dependent on the difference between the higher blood pressure created by vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole versus the lower blood pressure created by lesser vasoconstriction of the efferent arteriole.

GFR is equal to the renal clearance rate when any solute is freely filtered and is neither reabsorbed nor secreted by the kidneys. The rate therefore measured is the quantity of the substance in the urine that originated from a calculable volume of blood. Relating this principle to the below equation – for the substance used, the product of urine concentration and urine flow equals the mass of substance excreted during the time that urine has been collected. This mass equals the mass filtered at the glomerulus as nothing is added or removed in the nephron. Dividing this mass by the plasma concentration gives the volume of plasma which the mass must have originally come from, and thus the volume of plasma fluid that has entered Bowman's capsule within the aforementioned period of time. The GFR is typically recorded in units of volume per time, e.g., milliliters per minute (mL/min). Compare to filtration fraction.

There are several different techniques used to calculate or estimate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR or eGFR). The above formula only applies for GFR calculation when it is equal to the Clearance Rate.

Measurement

Creatinine

In clinical practice, however, creatinine clearance or estimates of creatinine clearance based on the serum creatinine level are used to measure GFR. [5]Creatinine is produced naturally by the body (creatinine is a breakdown product of creatine phosphate, which is found in muscle). It is freely filtered by the glomerulus, but also actively secreted by the peritubular capillaries in very small amounts such that creatinine clearance overestimates actual GFR by 10% to 20%. This margin of error is acceptable, considering the ease with which creatinine clearance is measured. Unlike precise GFR measurements involving constant infusions of inulin, creatinine is already at a steady-state concentration in the blood, and so measuring creatinine clearance is much less cumbersome. However, creatinine estimates of GFR have their limitations. All of the estimating equations depend on a prediction of the 24-hour creatinine excretion rate, which is a function of muscle mass which is quite variable. One of the equations, the Cockcroft and Gault equation (see below) does not correct for race. With a higher muscle mass, serum creatinine will be higher for any given rate of clearance.

Inulin

The GFR can be determined by injecting inulin or the inulin-analog sinistrin into the blood stream. Since both inulin and sinistrin are neither reabsorbed nor secreted by the kidney after glomerular filtration, their rate of excretion is directly proportional to the rate of filtration of water and solutes across the glomerular filter. Incomplete urine collection is an important source of error in inulin clearance measurement.[6] Using inulin to measure kidney function is the "gold standard" for comparison with other means of estimating glomerular filtration rate.[7]

Radioactive tracers

GFR can be accurately measured using radioactive substances, in particular chromium-51 and technetium-99m. These come close to the ideal properties of inulin (undergoing only glomerular filtration) but can be measured more practically with only a few urine or blood samples.[8] Measurement of renal or plasma clearance of 51Cr-EDTA is widely used in Europe but not available in the United States, where 99mTc-DTPA may be used instead.[9] Renal and plasma clearance 51Cr-EDTA has been shown to be accurate in comparison with the gold standard, inulin.[10][11][12] Use of 51Cr‑EDTA is considered a reference standard measure in UK guidance.[13]

Cystatin C

Problems with creatinine (varying muscle mass, recent meat ingestion (much less dependent on the diet than urea), etc.) have led to evaluation of alternative agents for estimation of GFR. One of these is cystatin C, a ubiquitous protein secreted by most cells in the body (it is an inhibitor of cysteine protease).

Cystatin C is freely filtered at the glomerulus. After filtration, Cystatin C is reabsorbed and catabolized by the tubular epithelial cells, with only small amounts excreted in the urine. Cystatin C levels are therefore measured not in the urine, but in the bloodstream.

Equations have been developed linking estimated GFR to serum cystatin C levels. Most recently, some proposed equations have combined (sex, age and race) adjusted cystatin C and creatinine. The most accurate is (sex, age and race) adjusted cystatin C, followed by (sex, age and race) adjusted creatinine and then cystatine C alone in slightly different with adjusted creatinine.[14]

Calculation

More precisely, GFR is the fluid flow rate between the glomerular capillaries and the Bowman's capsule:

Where:

- is the GFR.

- is called the filtration constant and is defined as the product of the hydraulic conductivity and the surface area of the glomerular capillaries.

- is the hydrostatic pressure within the glomerular capillaries.

- is the hydrostatic pressure within the Bowman's capsule.

- is the colloid osmotic pressure within the glomerular capillaries.

- and is the colloid osmotic pressure within the Bowman's capsule.

Kf

Because this constant is a measurement of hydraulic conductivity multiplied by the capillary surface area, it is almost impossible to measure physically. However, it can be determined experimentally. Methods of determining the GFR are listed in the above and below sections and it is clear from our equation that can be found by dividing the experimental GFR by the net filtration pressure:[15]

PG

The hydrostatic pressure within the glomerular capillaries is determined by the pressure difference between the fluid entering immediately from the afferent arteriole and leaving through the efferent arteriole. The pressure difference is approximated by the product of the total resistance of the respective arteriole and the flux of blood through it:[16]

Where:

- is the afferent arteriole pressure.

- is the hydrostatic pressure within the glomerular capillaries.

- is the efferent arteriole pressure.

- is the afferent arteriole resistance.

- is the efferent arteriole resistance.

- is the afferent arteriole flux.

- And, is the efferent arteriole flux.

PB

The pressure in the Bowman's capsule and proximal tubule can be determined by the difference between the pressure in the Bowman's capsule and the descending tubule:[16]

Where:

- is the pressure in the descending tubule.

- And, is the resistance of the descending tubule.

ΠG

Blood plasma has a good many proteins in it and they exert an inward directed force called the osmotic pressure on the water in hypotonic solutions across a membrane, i.e., in the Bowman's capsule. Because plasma proteins are virtually incapable of escaping the glomerular capillaries, this oncotic pressure is defined, simply, by the ideal gas law:[15][16]

Where:

- R is the universal gas constant

- T is the temperature.

- And, c is concentration in mol/L of plasma proteins (remember the solutes can freely diffuse through the glomerular capsule).

Clearance and filtration fraction

Filtration fraction

The filtration fraction is the amount of plasma that is actually filtered through the kidney. This can be defined using the equation:

FF=GFR/RPF

- FF is the filtration fraction

- GFR is the glomerular filtration rate

- RPF is the renal plasma flow

Normal human FF is 20%.

Renal clearance

Cx=(Ux)V/Px

- Cx is the clearance of X (normally in units of mL/min).

- Ux is the urine concentration of X.

- Px is the plasma concentration of X.

- V is the urine flow rate.

Estimation

In clinical practice, however, creatinine clearance or estimates of creatinine clearance based on the serum creatinine level are used to measure GFR. Creatinine is produced naturally by the body (creatinine is a breakdown product of creatine phosphate, which is found in muscle). It is freely filtered by the glomerulus, but also actively secreted by the peritubular capillaries in very small amounts such that creatinine clearance overestimates actual GFR by 10% to 20%. This margin of error is acceptable, considering the ease with which creatinine clearance is measured. Unlike precise GFR measurements involving constant infusions of inulin, creatinine is already at a steady-state concentration in the blood, and so measuring creatinine clearance is much less cumbersome. However, creatinine estimates of GFR have their limitations. All of the estimating equations depend on a prediction of the 24-hour creatinine excretion rate, which is a function of muscle mass which is quite variable. One of the equations, the Cockcroft and Gault equation (see below) does not correct for race. With a higher muscle mass, serum creatinine will be higher for any given rate of clearance.

A common mistake made when just looking at serum creatinine is the failure to account for muscle mass. Hence, an older woman with a serum creatinine of 1.4 mg/dL may actually have a moderately severe chronic kidney disease, whereas a young muscular male can have a normal level of renal function at this serum creatinine level. Creatinine-based equations should be used with caution in cachectic patients and patients with cirrhosis. They often have very low muscle mass and a much lower creatinine excretion rate than predicted by the equations below, such that a cirrhotic patient with a serum creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL may have a moderately severe degree of chronic kidney disease.

Estimated GFR (eGFR) is now recommended by clinical practice guidelines and regulatory agencies for routine evaluation of GFR whereas measured GFR (mGFR) is recommended as a confirmatory test when more accurate assessment is required.[3]

Creatinine clearance CCr

One method of determining GFR from creatinine is to collect urine (usually for 24 h) to determine the amount of creatinine that was removed from the blood over a given time interval. If one removes 1440 mg in 24 h, this is equivalent to removing 1 mg/min. If the blood concentration is 0.01 mg/mL (1 mg/dL), then one can say that 100 mL/min of blood is being "cleared" of creatinine, since, to get 1 mg of creatinine, 100 mL of blood containing 0.01 mg/mL would need to have been cleared.

Creatinine clearance (CCr) is calculated from the creatinine concentration in the collected urine sample (UCr), urine flow rate (Vdt), and the plasma concentration (PCr). Since the product of urine concentration and urine flow rate yields creatinine excretion rate, which is the rate of removal from the blood, creatinine clearance is calculated as removal rate per min (UCr×Vdt) divided by the plasma creatinine concentration. This is commonly represented mathematically as

Example: A person has a plasma creatinine concentration of 0.01 mg/mL and in 1 hour produces 60 mL of urine with a creatinine concentration of 1.25 mg/mL.

The common procedure involves undertaking a 24-hour urine collection, from empty-bladder one morning to the contents of the bladder the following morning, with a comparative blood test then taken. The urinary flow rate is still calculated per minute, hence:

To allow comparison of results between people of different sizes, the CCr is often corrected for the body surface area (BSA) and expressed compared to the average sized man as mL/min/1.73 m2. While most adults have a BSA that approaches 1.7 m2 (1.6 m2 to 1.9 m2), extremely obese or slim patients should have their CCr corrected for their actual BSA.

- BSA can be calculated on the basis of weight and height.

Twenty-four-hour urine collection to assess creatinine clearance is no longer widely performed, due to difficulty in assuring complete specimen collection. To assess the adequacy of a complete collection, one always calculates the amount of creatinine excreted over a 24-hour period. This amount varies with muscle mass and is higher in young people/old, and in men/women. An unexpectedly low or high 24-hour creatinine excretion rate voids the test. Nevertheless, in cases where estimates of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine are unreliable, creatinine clearance remains a useful test. These cases include "estimation of GFR in individuals with variation in dietary intake (vegetarian diet, creatine supplements) or muscle mass (amputation, malnutrition, muscle wasting), since these factors are not specifically taken into account in prediction equations."[17]

A number of formulae have been devised to estimate GFR or Ccr values on the basis of serum creatinine levels. Where not otherwise stated serum creatinine is assumed to be stated in mg/dL, not μmol/L—divide by 88.4 to convert from μmol/Lto mg/dL.

Cockcroft-Gault formula

A commonly used surrogate marker for the estimation of creatinine clearance is the Cockcroft-Gault (CG) formula, which in turn estimates GFR in ml/min:[18] It is named after the scientists, the asthmologist Donald William Cockcroft (b. 1946) and the nephrologist Matthew Henry Gault (1925–2003), who first published the formula in 1976, and it employs serum creatinine measurements and a patient's weight to predict the creatinine clearance.[19][20] The formula, as originally published, is:

- This formula expects weight to be measured in kilograms and creatinine to be measured in mg/dL, as is standard in the USA. The resulting value is multiplied by a constant of 0.85 if the patient is female. This formula is useful because the calculations are simple and can often be performed without the aid of a calculator.

When serum creatinine is measured in μmol/L:

- Where Constant is 1.23 for men and 1.04 for women.

One interesting feature of the Cockcroft and Gault equation is that it shows how dependent the estimation of CCr is based on age. The age term is (140 – age). This means that a 20-year-old person (140 – 20 = 120) will have twice the creatinine clearance as an 80-year-old (140 – 80 = 60) for the same level of serum creatinine. The C-G equation assumes that a woman will have a 15% lower creatinine clearance than a man at the same level of serum creatinine.

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula

Another formula for calculating the GFR is the one developed by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group.[21] Most laboratories in Australia,[22] and the United Kingdom now calculate and report the estimated GFR along with creatinine measurements and this forms the basis of diagnosis of chronic kidney disease.[23][24] The adoption of the automatic reporting of MDRD-eGFR has been widely criticised.[25][26][27]

The most commonly used formula is the "4-variable MDRD", which estimates GFR using four variables: serum creatinine, age, ethnicity, and gender.[28] The original MDRD used six variables with the additional variables being the blood urea nitrogen and albumin levels.[21] The equations have been validated in patients with chronic kidney disease; however, both versions underestimate the GFR in healthy patients with GFRs over 60 mL/min.[29][30] The equations have not been validated in acute renal failure.

For creatinine in μmol/L:

For creatinine in mg/dL:

- Creatinine levels in μmol/L can be converted to mg/dL by dividing them by 88.4. The 32788 number above is equal to 186×88.41.154.

A more elaborate version of the MDRD equation also includes serum albumin and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels:

- where the creatinine and blood urea nitrogen concentrations are both in mg/dL. The albumin concentration is in g/dL.

These MDRD equations are to be used only if the laboratory has NOT calibrated its serum creatinine measurements to isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS). When IDMS-calibrated serum creatinine is used (which is about 6% lower), the above equations should be multiplied by 175/186 or by 0.94086.[31]

Since these formulae do not adjust for body size, results are given in units of mL/min per 1.73 m2, 1.73 m2 being the estimated body surface area of an adult with a mass of 63 kg and a height of 1.7m.

CKD-EPI formula

The CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) formula was published in May 2009. It was developed in an effort to create a formula more accurate than the MDRD formula, especially when actual GFR is greater than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This is the formula currently recommended by NICE in the UK.[24]

Researchers pooled data from multiple studies to develop and validate this new equation. They used 10 studies that included 8254 participants, randomly using 2/3 of the data sets for development and the other 1/3 for internal validation. Sixteen additional studies, which included 3896 participants, were used for external validation.

The CKD-EPI equation performed better than the MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study) equation, especially at higher GFR, with less bias and greater accuracy. When looking at NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data, the median estimated GFR was 94.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 vs. 85.0 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and the prevalence of chronic kidney disease was 11.5% versus 13.1%. Despite its overall superiority to the MDRD equation, the CKD-EPI equations performed poorly in certain populations, including black women, the elderly and the obese, and was less popular among clinicians than the MDRD estimate.[32]

The CKD-EPI equation is:

where SCr is serum creatinine (mg/dL), k is 0.7 for females and 0.9 for males, a is −0.329 for females and −0.411 for males, min indicates the minimum of SCr/k or 1, and max indicates the maximum of SCr/k or 1.

As separate equations for different populations: For creatinine (IDMS calibrated) in mg/dL:

- Male, not black

- If serum creatinine (Scr) ≤ 0.9

- If serum creatinine (Scr) > 0.9

- Female, not black

- If serum creatinine (Scr) ≤ 0.7

- If serum creatinine (Scr) > 0.7

- Black male

- If serum creatinine (Scr) ≤ 0.9

- If serum creatinine (Scr) > 0.9

- Black female

- If serum creatinine (Scr) ≤ 0.7

- If serum creatinine (Scr) > 0.7

This formula was developed by Levey et al.[33]

The formula CKD-EPI may provide improved cardiovascular risk prediction over the MDRD Study formula in a middle-age population.[34]

Mayo Quadratic formula

Another estimation tool to calculate GFR is the Mayo Quadratic formula. This formula was developed by Rule et al.,[29] in an attempt to better estimate GFR in patients with preserved kidney function. It is well recognized that the MDRD formula tends to underestimate GFR in patients with preserved kidney function. Studies in 2008 found that the Mayo Clinic Quadratic Equation compared moderately well with radionuclide GFR, but had inferior bias and accuracy than the MDRD equation in a clinical setting.[35][36]

The equation is:

If Serum Creatinine < 0.8 mg/dL, use 0.8 mg/dL for Serum Creatinine.

Schwartz formula

In children, the Schwartz formula is used.[37][38] This employs the serum creatinine (mg/dL), the child's height (cm) and a constant to estimate the glomerular filtration rate:

- Where k is a constant that depends on muscle mass, which itself varies with a child's age:

The method of selection of the constant k has been questioned as being dependent upon the gold-standard of renal function used (i.e. inulin clearance, creatinine clearance, etc.) and also may be dependent upon the urinary flow rate at the time of measurement.[40]

In 2009 the formula was updated to use standardized serum creatinine (recommend k=0.413) and additional formulas that allow improved precision were derived if serum cystatin C is measured in addition to serum creatinine.[41]

IDMS standardization effort

One problem with any creatinine-based equation for GFR is that the methods used to assay creatinine in the blood differ widely in their susceptibility to non-specific chromogens, which cause the creatinine value to be overestimated. In particular, the MDRD equation was derived using serum creatinine measurements that had this problem. The NKDEP program in the United States has attempted to solve this problem by trying to get all laboratories to calibrate their measures of creatinine to a "gold standard", which in this case is isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS). In late 2009 not all labs in the U.S. had changed over to the new system. There are two forms of the MDRD equation that are available, depending on whether or not creatinine was measured by an IDMS-calibrated assay. The CKD-EPI equation is designed to be used with IDMS-calibrated serum creatinine values only.

Normal ranges

The normal range of GFR, adjusted for body surface area, is 100–130 average 125 mL/min/1.73m2 in men and 90–120 ml/min/1.73m2 in women younger than the age of 40. In children, GFR measured by inulin clearance is 110 mL/min/1.73 m2 until 2 years of age in both sexes, and then it progressively decreases. After age 40, GFR decreases progressively with age, by 0.4–1.2 mL/min per year.

Decreased GFR

A decreased renal function can be caused by many types of kidney disease. Upon presentation of decreased renal function, it is recommended to perform a history and physical examination, as well as performing a renal ultrasound and a urinalysis. The most relevant items in the history are medications, edema, nocturia, gross hematuria, family history of kidney disease, diabetes and polyuria. The most important items in a physical examination are signs of vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, diabetes, endocarditis and hypertension.

A urinalysis is helpful even when not showing any pathology, as this finding suggests an extrarenal etiology. Proteinuria and/or urinary sediment usually indicates the presence of glomerular disease. Hematuria may be caused by glomerular disease or by a disease along the urinary tract.

The most relevant assessments in a renal ultrasound are renal sizes, echogenicity and any signs of hydronephrosis. Renal enlargement usually indicates diabetic nephropathy, focal segmental glomerular sclerosis or myeloma. Renal atrophy suggests longstanding chronic renal disease.

Chronic kidney disease stages

Risk factors for kidney disease include diabetes, high blood pressure, family history, older age, ethnic group and smoking. For most patients, a GFR over 60 mL/min/1.73m2 is adequate. But significant decline of the GFR from a previous test result can be an early indicator of kidney disease requiring medical intervention. The sooner kidney dysfunction is diagnosed and treated the greater odds of preserving remaining nephrons, and preventing the need for dialysis.

| CKD stage | GFR level (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 | ≥ 90 |

| Stage 2 | 60–89 |

| Stage 3 | 30–59 |

| Stage 4 | 15–29 |

| Stage 5 | < 15 |

The severity of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is described by six stages; the most severe three are defined by the MDRD-eGFR value, and first three also depend on whether there is other evidence of kidney disease (e.g., proteinuria):

- 0) Normal kidney function – GFR above 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 and no proteinuria

- 1) CKD1 – GFR above 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 with evidence of kidney damage

- 2) CKD2 (mild) – GFR of 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 with evidence of kidney damage

- 3) CKD3 (moderate) – GFR of 30 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2

- 4) CKD4 (severe) – GFR of 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m2

- 5) CKD5 kidney failure – GFR less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 Some people add CKD5D for those stage 5 patients requiring dialysis; many patients in CKD5 are not yet on dialysis.

Note: others add a "T" to patients who have had a transplant regardless of stage.

Not all clinicians agree with the above classification, suggesting that it may mislabel patients with mildly reduced kidney function, especially the elderly, as having a disease.[42][43] A conference was held in 2009 regarding these controversies by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) on CKD: Definition, Classification and Prognosis, gathering data on CKD prognosis to refine the definition and staging of CKD.[44]

See also

References

- Ganong (2016). "Renal Function & Micturition". Review of Medical Physiology, 25th ed. McGraw-Hill Education. p. 677. ISBN 978-0-07-184897-8.

- Stevens, Paul E.; Levin, Adeera (Jun 4, 2013). "Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline". Annals of Internal Medicine. 158 (11): 825–830. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007. ISSN 1539-3704. PMID 23732715.

- Levey AS; Coresh J; Tighiouart H; Greene T; Inker LA (2020). "Measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate: current status and future directions". Nat Rev Nephrol. 16 (1): 51–64. doi:10.1038/s41581-019-0191-y. PMID 31527790. S2CID 202573933.

- Nosek, Thomas M. "Section 7/7ch04/7ch04p11". Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 2016-03-24. – "Glomerular Filtration Rate"

- "Renal Nephron Filtration | John Jay College of Criminal Justice - KeepNotes". keepnotes.com. Retrieved 2023-05-26.

- Rose GA (1969). "Measurement of glomerular filtration rate by inulin clearance without urine collection". BMJ. 2 (5649): 91–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5649.91. PMC 1982852. PMID 5775456.

- Hsu, CY; Bansal, N (August 2011). "Measured GFR as "gold standard"--all that glitters is not gold?". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 6 (8): 1813–4. doi:10.2215/cjn.06040611. PMID 21784836.

- Murray, A. W.; Barnfield, M. C.; Waller, M. L.; Telford, T.; Peters, A. M. (8 May 2013). "Assessment of Glomerular Filtration Rate Measurement with Plasma Sampling: A Technical Review". Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology. 41 (2): 67–75. doi:10.2967/jnmt.113.121004. PMID 23658207.

- Speeckaert, Marijn; Delanghe, Joris (2015). "Assessment of renal function". In Giuseppe, Daniel; Winearls, Christopher; Remuzzi, Giuseppe (eds.). Oxford Textbook of Clinical Nephrology (Fourth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780199592548.

- Henriksen, Ulrik L.; Henriksen, Jens H. (January 2015). "The clearance concept with special reference to determination of glomerular filtration rate in patients with fluid retention". Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging. 35 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1111/cpf.12149. PMID 24750696. S2CID 44756080.

- Soveri, Inga; Berg, Ulla B.; Björk, Jonas; Elinder, Carl-Gustaf; Grubb, Anders; Mejare, Ingegerd; Sterner, Gunnar; Bäck, Sten-Erik (September 2014). "Measuring GFR: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 64 (3): 411–424. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.04.010. PMID 24840668.

- Hsu, C.-y.; Bansal, N. (22 July 2011). "Measured GFR as 'Gold Standard'—All That Glitters Is Not Gold?". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 6 (8): 1813–1814. doi:10.2215/CJN.06040611. PMID 21784836.

- "Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management". NICE. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, et al. (March 2008). "Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: a pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 51 (3): 395–406. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.018. PMC 2390827. PMID 18295055.

- Guyton, Arthur; Hall, John (2006). "Chapter 26: Urine Formation by the Kidneys: I. Glomerular Filtration, Renal Blood Flow, and Their Control". In Gruliow, Rebecca (ed.). Textbook of Medical Physiology (Book) (11th ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier Inc. pp. 308–325. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- Keener, James; Sneyd, James (2004). "20: Renal Physiology". In Marsden, J.E. (ed.). Mathematical Physiology (Book). Interdisciplinary Mathematics. Vol. 8 (Mathematical Biology). Sirovich, Wiggins (1st ed.). Springer. pp. 612–636. doi:10.1007/0-387-22706-7_20. ISBN 978-0-387-98381-3.

- "KDOQI CKD Guidelines". Archived from the original on 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- GFR Calculator at cato.at – Cockcroft-Gault Archived 2004-09-05 at the Wayback Machine – GFR calculation (Cockcroft-Gault formula)

- Cockcroft DW, Gault MH (1976). "Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine". Nephron. 16 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1159/000180580. PMID 1244564.

- Gault MH, Longerich LL, Harnett JD, Wesolowski C (1992). "Predicting glomerular function from adjusted serum creatinine". Nephron. 62 (3): 249–56. doi:10.1159/000187054. PMID 1436333.

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D (March 1999). "A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group". Annals of Internal Medicine. 130 (6): 461–70. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. PMID 10075613. S2CID 1902375.

- Mathew TH, Johnson DW, Jones GR (October 2007). "Chronic kidney disease and automatic reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate: revised recommendations". The Medical Journal of Australia. 187 (8): 459–63. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01357.x. PMID 17937643. S2CID 14920030.

- Joint Specialty Committee on Renal Disease (June 2005). "Chronic kidney disease in adults: UK guidelines for identification, management and referral" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-19.

- www.nice.org.uk (July 2014). "Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management".

- Davey RX (January 2006). "Chronic kidney disease and automatic reporting of estimated glomerular filtration rate". The Medical Journal of Australia. 184 (1): 42–3, author reply 43. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00098.x. hdl:2440/34660. PMID 16398632. S2CID 9648508.

- Twomey PJ, Reynolds TM (November 2006). "The MDRD formula and validation". QJM. 99 (11): 804–5. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcl108. PMID 17041249.

- Kallner A, Ayling PA, Khatami Z (2008). "Does eGFR improve the diagnostic capability of S-Creatinine concentration results? A retrospective population based study". International Journal of Medical Sciences. 5 (1): 9–17. doi:10.7150/ijms.5.9. PMC 2204044. PMID 18219370. S2CID 14970724.

- National Kidney Foundation (February 2002). "K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 39 (2 Suppl 1): S1–266. doi:10.1016/S0272-6386(02)70081-4. PMID 11904577.

- Rule AD, Larson TS, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Jacobsen SJ, Cosio FG (December 2004). "Using serum creatinine to estimate glomerular filtration rate: accuracy in good health and in chronic kidney disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 141 (12): 929–37. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00009. PMID 15611490. S2CID 30342139.

- Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. (August 2006). "Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate". Annals of Internal Medicine. 145 (4): 247–54. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. PMID 16908915. S2CID 37149831.

- "GFR MDRD Calculator for Adults". National Kidney Disease Education Program. United States: National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- Hougardy, JM; Delanaye, P; Le Moine, A; Nortier, J (2014). "Estimation of the glomerular filtration rate in 2014 by tests and equations: strengths and weaknesses". Rev Med Brux. (in French). 35 (4): 250–7. PMID 25675627.

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. (May 2009). "A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate". Annals of Internal Medicine. 150 (9): 604–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. PMC 2763564. PMID 19414839.

- Matsushita K, Selvin E, Bash LD, Astor BC, Coresh J (April 2010). "Risk implications of the new CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation compared with the MDRD Study equation for estimated GFR: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 55 (4): 648–59. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.016. PMC 2858455. PMID 20189275.

- Saleem, Mohamed; Florkowski, Christopher M; George, Peter M (2008). "Comparison of the Mayo Clinic Quadratic Equation with the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation and radionuclide glomerular filtration rate in a clinical setting". Nephrology. 13 (8): 684–688. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01045.x. ISSN 1320-5358. PMID 19154321. S2CID 45943783.

- Fontsere, N.; Bonal, J.; Salinas, I.; de Arellano, M. R.; Rios, J.; Torres, F.; Sanmarti, A.; Romero, R. (2008). "Is the New Mayo Clinic Quadratic Equation Useful for the Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate in Type 2 Diabetic Patients?". Diabetes Care. 31 (12): 2265–2267. doi:10.2337/dc08-0958. ISSN 0149-5992. PMC 2584175. PMID 18835955. S2CID 24211196.

- Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Spitzer A (August 1976). "A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine". Pediatrics. 58 (2): 259–63. doi:10.1542/peds.58.2.259. PMID 951142.

- Schwartz GJ, Feld LG, Langford DJ (June 1984). "A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in full-term infants during the first year of life". The Journal of Pediatrics. 104 (6): 849–54. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(84)80479-5. PMID 6726515.

- Brion LP, Fleischman AR, McCarton C, Schwartz GJ (October 1986). "A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in low birth weight infants during the first year of life: noninvasive assessment of body composition and growth". The Journal of Pediatrics. 109 (4): 698–707. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(86)80245-1. PMID 3761090.

- Haenggi MH, Pelet J, Guignard JP (February 1999). "Estimation of glomerular filtration rate by the formula GFR = K x T/Pc". Archives de Pédiatrie (in French). 6 (2): 165–72. doi:10.1016/S0929-693X(99)80204-8. PMID 10079885.

- Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, et al. (March 2009). "New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 20 (3): 629–37. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008030287. PMC 2653687. PMID 19158356.

- Bauer C, Melamed ML, Hostetter TH (2008). "Staging of Chronic Kidney Disease: Time for a Course Correction". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 19 (5): 844–46. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008010110. PMID 18385419.

- Eckardt KU, Berns JS, Rocco MV, Kasiske BL (June 2009). "Definition and Classification of CKD: The Debate Should Be About Patient Prognosis—A Position Statement From KDOQI and KDIGO" (PDF). American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 53 (6): 915–920. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.001. PMID 19406541. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-25.

- "KDIGO Controversies Conference: Definition, Classification and Prognosis in CKD, London, October 2009". Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-11-24.

External links

Online calculators

- Online GFR Calculator

- Schwartz formula for estimating pediatric renal function

- Creatinine clearance calculator (Cockcroft-Gault Equation)- by MDCalc

- MDRD GFR Equation

- GFR calculator using Cystatin C

Reference links

- National Kidney Disease Education Program website. Includes professional references and GFR calculators

- eGFR at Lab Tests Online