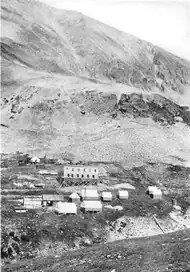

Climax mine

The Climax mine, located in Climax, Colorado, United States, is a major molybdenum mine in Lake and Summit counties, Colorado. Shipments from the mine began in 1915. At its highest output, the Climax mine was the largest molybdenum mine in the world, and for many years it supplied three quarters of the world's supply of molybdenum.

After a long shutdown, the Climax mine reopened and resumed shipment of molybdenum on May 10, 2012. The mine is owned by Climax Molybdenum Company, a subsidiary of Freeport-McMoRan.

History

The prospector Charles Senter discovered and claimed the outcropping of molybdenite (molybdenum sulfide) veins in 1879, during the Leadville, Colorado Silver Boom, but had no idea what the mineral there was. Senter determined that the rock contained no gold or silver, but retained the claims. The following year he settled with his Ute wife a few miles north, and he made a living working a nearby gold placer. Each year he performed the assessment work required to maintain his lode claims, convinced that his mystery mineral must be of value. In 1918 Senter received US$40,000 for his mining claims and "settled into a comfortable retirement in Denver."[1]

Although Senter finally found a chemist who identified the gray mineral as containing molybdenum in 1895, at the time there was virtually no market for the metal. When steelmakers determined the utility of molybdenum as an alloy in producing hard steel, the first ore shipments from the deposit began in 1915, and the Climax mine began full production in 1914. The main ore bearing area was Bartlett Mountain, which was mined out during the early mining. The demand for molybdenum fell drastically at the end of World War I, and the Climax mine shut down in 1919.[2] Molybdenum later found use in the metal alloys for the turbines of jet engines. Molybdenum is an important metal used in industrial work to increase the resistance of steel because of its much higher melting point compared to that of iron.[3] Molybdenum was also used to fight weather erosion, friction, and chemical exposure of industrial equipment.[4] The extraction of molybdenite hit its highest during World War I, when the army realized that the Germans were using molybdenum as an alloy to strengthen and increase the durability of their weapons and tanks.[5]

The Climax Molybdenum Company re-opened the mine in 1924, and it operated the mine nearly continuously until the 1980s. The mine was shut down between 1995 and 2012 due to low molybdenum prices. The mine's owner, Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold, continued to work on environmental cleanup of past operations while holding the mine ready in the event of market changes.

In December 2007 Freeport-McMoRan reported that it planned to reopen the Climax mine and that production should start in 2010. An initial $500-million project involves the restart of open-pit mining and construction of state-of-the-art milling facilities.[6] The company stated that the Climax mine has "... the largest, highest-grade and lowest-cost molybdenum ore body in the world.".[7] The remaining ore reserves are estimated to contain about 500 million pounds of molybdenum, contained in ore at an average molybdenum percentage of 0.165%. Production was expected to be about 30 million pounds per year, starting in 2010.[8]

Due to lower molybdenum prices, Freeport-McMoRan announced in November 2008 that it was deferring the plan to reopen the Climax mine.[9][10] At the time, the company had spent about US$200 million preparing for a restart of the mine, with an estimated US$350 million more needed to complete the capital improvements and reopen.[11] In May 2012, following a 17-year shutdown, the Climax mine reopened and resumed shipment of molybdenum.[11][12]

Geology

The ore deposit is a porphyry type, similar to many large copper deposits, where many intersecting small veins of molybdenite form a stockwork in an altered quartz monzonite porphyry. Like other porphyry-type ore deposits, the ore is low-grade, much less than one percent molybdenum, but the ore bodies are very large. Beside molybdenum, the mine has also produced tin (from cassiterite), tungsten (from hübnerite), and pyrite as by-products.

The rocks of the Climax Stock are alkaline felsic intrusives. They range from porphyritic alkaline rhyolite to alkaline aplite to porphyritic alkaline granite. In map view, the igneous bodies of the Climax Stock form a roughly circular structure. In cross-section view, each intrusion has an inverted bowl shape.

Published studies on the origin of the Climax Molybdenum Deposit and other Climax-type moly deposits have concluded that they form principally in incipient extensional tectonic settings well inland from shallow-angle subduction zones that have recently ceased.[13]

The Climax deposit is one of a number of large molybdenum deposits in central Colorado and northern New Mexico. Other molybdenum deposits in the region include the Questa mine in New Mexico, and the Henderson and Urad mines near Empire, Colorado.

Mining

Historically, mining was principally by "sub-level induced panel caving", a method that removes ore by undercutting the base of a panel in the ore deposit, causing the rock above to break and drop down in a controlled manner. The method allowed economical extraction of the large low-grade ore deposit. Current mining operations at Climax are via an open-pit.

The ore is crushed on-site, and the molybdenite is separated from the waste material by froth flotation, which mixes pulverized ore into a slurry of air, water, surfactants, and other chemicals.

The large quantities of waste slurry flows into nearby reservoirs on the adjacent stream drainage to the north. Most of the liquid is drained and the remaining solid pulverized minerals and waste are called tailings. When full—as seen from the highway—these tailings reservoirs look quite striking; something like a cross between a reservoir and a dammed mountain meadow. The Climax tailing impoundment now covers several square miles.

Geography

The Climax mine is located at 39°21′57″N 106°11′09″W (39.365890,-106.185780) at an elevation of about 11,360 feet (3,460 meters). It is on Fremont Pass, along the Continental Divide.

Remediation and reclamation

About 20 different federal or state agencies affected Climax operations, including the U.S. EPA, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management.

In 1991, the mine declared the Storke Level ore abandoned; no more ore could be extracted profitably, so the company redirected its focus to other activities, such as open-pit reclamation, the haulage of open-pit waste to the tailings dam, and hydromulching, among others. Climax also started the reclamation of a particular highly acidic tailing pond at the head of the Eagle River drainage. It sold the water rights to a company from Vail and started the process of removing and neutralizing the acid tailings to convert the pond to a freshwater reservoir. To do this, they used a “hydrology mining” process to extract the tailings from the bedrock it had been sitting on for several decades. This process converted the compacted tailings to a water slurry that could be easily piped into a pond where it would be chemically neutralized.

In 1994, the mine labor force was reduced to 24 employees who were working on five different tasks, including treating water and maintaining environmental quality, environmental reclamation and development of water resources.[14]

Ground surface subsidence started around 1920 on Bartlett mountain. By 2001, the subsidence area covered about 100 acres on Bartlett mountain. Around the open-pit, caved ground combined with winter avalanches and high vertical pit walls make the West side of the mountain even more susceptible to collapse. Also, the cracks through the rocks created by shifting blocks allow ground water to infiltrate into the working tunnels, increasing the potential for acid rock drainage from the mine.[15]

Further reading

- Paul B. Coffman (1937). "The Rise of a New Metal: The Growth and Success of the Climax Molybdenum Company". The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago. 10 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1086/232443. JSTOR 2349563.

- Voynick, Steve (2004). "Climax, Two Decades Later". Colorado Central Magazine. 125: 16. Archived from the original on 2006-10-14. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

References

- Steve Voynick (1996) "Climax", Mountain Press Publishing Company, September 1997. This company owns about 50% of Colorado mines. It is relied on by many miners to make profit.

- Stewart R. Wallace and others (1968) Multiple Intrusion and Mineralization at Climax, Colorado, in Ore Deposits in the United States 1933/1967, v.1, New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers, p.605-664.

- Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. 2004-2001. “What is molybdenum”. Web.

- Paul B. Coffman (1937) The Rise of a New Metal: The Growth and Success of the Climax Molybdenum Company. The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago. Vol. 10, No 1. Jan. 1937 pp. 35-40

- Gillian Klucas(2004) Leadville: the struggle to revive an American town. Washington, DC : Island Press. Print.

- Marcia Martinek, It's a go; Climax Mine will reopen, Leadville Herald Democrat, 6 Dec. 2007, p.1, c.1.

- Steve Raabe, Leadville's hopes raised for Climax mine opening, Denver Post, 25 Oct. 2007, p.C1, c.1.

- "Freeport to proceed with Climax moly mine restart," Engineering & Mining Journal, Dec. 2007, p.8-10.

- Andy Vuong, "Climax redux cut short," Denver Post, 11 Nov. 2008, p.5B c.1.

- "Restart of Climax Mine Near Leadville Postponed" Archived 2016-05-19 at the Portuguese Web Archive, November 10th, 2008

- Archived 2012-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, Summit Daily News (Frisco, CO), May 10, 2012

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23. Retrieved 2013-02-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Climax Molybdenum Press Release - Climax Molybdenum Deposit, class notes, Ohio State University

- Stephen Voynick (1996) Climax: the history of Colorado’s Climax Molybdenum mine. Mountain Press Publishing Company Missoula, Montana. Print.

- Steve Blodgett (2002) Subsidence Impacts at the Molycorp Molybdenum Mine Questa, New Mexico. Center for Science in Public Participation. Web.