Cletus Bél

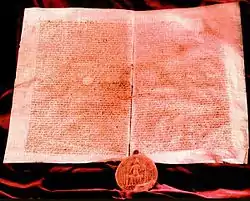

Cletus from the kindred Bél (Hungarian: Bél nembeli Kilit; died December 1245) was a Hungarian prelate in the first half of the 13th century, who served as Bishop of Eger from 1224 to 1245. As royal chancellor, he drafted the Golden Bull of 1222 issued by King Andrew II of Hungary.

Cletus Bél | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Eger | |

| Appointed | 1224 |

| Term ended | 1245 |

| Predecessor | Thomas |

| Successor | Lampert Hont-Pázmány |

| Other post(s) | Chancellor |

| Personal details | |

| Died | December 1245 |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

Early career

Given by the hand of Cletus, chancellor of our [King Andrew II's royal] court and provost of the church of Eger, in the year of the Incarnation of the Word one thousand two hundred twenty-two, [...] in the seventeenth year of our reign.

Cletus was plausibly born into the gens (clan) Bél (also known as Ug) of ancient Hungarian origin, which possessed villages and landholdings in the valley of Bél Rock between the mountain ranges Mátra and Bükk, in the territory of Borsod and Heves counties. His parentage, however, is unknown.[2] He studied canon law in a foreign university in Western Europe.[3] Returning to Hungary, Cletus became the provost of the cathedral chapter of Eger by the spring of 1219; he is the earliest known cleric, who held that position. King Andrew II appointed him royal chancellor in the same year.[4] He first appeared in this dignity, when the monarch granted Alvinc (today Vințu de Jos, Romania) to the Archdiocese of Esztergom, and Cletus formulated the royal donation letter.[5] Historian Andor Csizmadia considered Cletus already functioned as provost in 1217, when Thomas was elected as Bishop of Eger by the cathedral chapter, who, in return, introduced him to the royal court.[5]

As royal chancellor, Cletus drafted the Golden Bull of 1222, which summarized the liberties of the royal servants, including their exemption from taxes and the jurisdiction of the counties and clearly distinguished them from the king's other subjects, which led to the rise of the Hungarian nobility. The document, often compared to the contemporary Magna Carta, defined the Hungarian legal system for centuries until the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.[6] From the time of his chancellorship, the royal charters began to use "et aliis quam, pluribus magistratus et comitatus tenentibus" formulas at the end of the documents, where listed the most dignitaries of the kingdom instead of the eyewitnesses and countersignatories actually present. With this phrase, he extended the barons of the realm with office-holders of courtly positions outlined under the collective concept of "existentibus", and finally, in 1222, he considered it necessary to attempt a general change in his chancellery. He extended the phrase "tenitibus comitatus" – in line with the changes in the hierarchy of the aristocracy – to launch a decades-long practice, concluding the list of laity with the aforementioned new extended formula.[7]

Bishop of Eger

Thomas was transferred to the Archdiocese of Esztergom in early 1224. Cletus Bél was elected as his successor shortly thereafter.[8] In that year, two subsequent charters referred to him as bishop-elect, but then two another documents styled him simply bishop, consequently Pope Honorius III confirmed his election still in 1224.[6] The pope trusted in his legal expertise; after Thomas' sudden death in late 1224, the cathedral chapter of Esztergom could not agree unanimously about the new archbishop and the canons elected two prelates – Desiderius of Csanád and James of Nyitra (Nitra) – to the position simultaneously. Pope Honorius entrusted Cletus and Briccius of Vác in 1225 to visit the archiepiscopal see and persuade the clergymen to elect their new archbishop in accordance with the canonical rules of procedure.[6] Around the same time, Cletus Bél complained the poor situation of the Eger Chapter to Pope Honorius, who consequently authorized the bishop to attach the various chapels of the cathedral to the offices of canons as a source of funding on 25 September 1225 – despite the regulations of the third and fourth councils of the Lateran.[6]

_(5433._sz%C3%A1m%C3%BA_m%C5%B1eml%C3%A9k)_7.jpg.webp)

Sometime after 1229, Cletus invited Franciscans to Eger, where he established their monastery.[5] Formerly, some historians – including Márton Szentiványi – erroneously considered this was the first Franciscan convent in Hungary.[9] Cletus also established his clan's monastery on 16 May 1232, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. The monastery was called Bélháromkút Abbey ("Trium fontium de Beel"), because it was erected between three spring waters near present-day Bélapátfalva, the ancient estate of the Bél kindred (his secular relatives became patrons of the monastery).[5] Upon the intercession of papal legate Giacomo di Pecorari, Cletus invited Cistercians from Pilis Abbey to his newly established monastery.[10] Cletus donated the villages of Apátfalva, Királd, Ostoros, Arnót, Horváti, Mercse, Csokva, Dochond, Pazman, Medsa, Magy, Kisdukány, Csen and Velyn, in addition to three fishponds along the river Tisza to the Bélháromkút Abbey.[5] With the consent of the Eger Chapter, Cletus also granted the fiftieth part of the episcopal tithe to the monastery. His donations were confirmed by Pope Gregory IX in 1239 and Pope Innocent IV in 1253.[11] The establishing charter of the Bélháromkút Abbey was transcribed by Bishop Csanád Telegdi in 1330.[10] Beside the two aforementioned convents, Cletus re-established the St. James hospital in Eger, when he subordinated the institution again to help the poor and sick, overriding the decision of his unnamed predecessors (possibly Katapán and Thomas), who converted the hospital into a church benefice. Pope Gregory IX confirmed this act on 7 March 1240 upon the request of its rector.[12]

Cletus, along with Robert, Archbishop of Esztergom, Gregory, Bishop of Győr, Palatine Denis, son of Ampud and other dignitaries, took the cross as a token of his desire to participate a crusade to the Holy Land. However Pope Gregory absolved them from oath in 1231; instead, he urged them to send financial aid to the Latin Empire. By the early 1230s, Andrew II embroiled conflict with the Holy See over the employment of Jews and Muslims in the royal administration. Archbishop Robert excommunicated Palatine Denis and other advisors, and put Hungary under an interdict on 25 February 1232. Cletus also countersigned the document. Pope Gregory sought an agreement and sent Cardinal Giacomo di Pecorari to the kingdom. On 20 August 1233, in the forests of Bereg in the territory of the Diocese of Eger, Andrew II reconciled with the Church.[9] According to a letter of Pope Gregory IX sent to Cletus and four other Hungarian prelates from 1235, a significant number of Muslim ("Saracen" or Böszörmény) communities lived in the territory of the Bishopric of Eger.[12]

During the First Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1241–42, the Diocese of Eger, along with the town and its cathedral suffered severe damage, while the episcopal treasuries were looted. Cletus Bél managed to survive the invasion, but his whereabouts during the events are unknown. It is plausible that he did not belong to the accompaniment of Béla IV of Hungary, who took refugee in Dalmatia.[12] Cletus had to reorganize the church institution in his diocese; he requested Béla IV to transcribe and confirm the privileges of the bishopric. In 1245, the vicars of the diocese complained to Pope Innocent IV that Cletus, the chapter, as well as the archdeacons, had confiscated all the church income for themselves, which made their livelihood impossible. The pope appointed subdeacon Martin to investigate the case and called the bishop to treat the vicars fairly.[13] Cletus was last mentioned as a living person on 12 December 1245. He died still in that month, as his successor Lampert Hont-Pázmány was already styled as bishop-elect in 1245.[8] According to a later document, Cletus granted nobility of church ("nobilis ecclesiæ") to a certain Samuel, son of Sibin. However, after Cletus' death, this Samuel gathered and set fire to the formerly reissued privilege letters of the diocese for unknown reasons. Avoid retaliation, Samuel fled to Ruthenia.[13] Greek Catholic priest and historian János Szarka considered the Diocese of Eger initially followed Byzantine (or Greek) Rite which, however, gradually switched to the Latin rite during the episcopal activities of Thomas and Cletus. Accordingly, the latter had already rewritten the privileges of the diocese according to the new rite after the Mongol invasion. Szarka argued Samuel was a cleric who practiced Greek rite, and this was the reason for the destruction of the diplomas.[14]

References

- The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary pp. 170–171.

- Csizmadia 1981, p. 10.

- Markó 2006, p. 307.

- Zsoldos 2011, p. 108.

- Csizmadia 1981, p. 11.

- Sugár 1984, p. 69.

- Nógrády 1995, pp. 157, 168.

- Zsoldos 2011, p. 88.

- Sugár 1984, p. 70.

- Sugár 1984, p. 71.

- Csizmadia 1981, p. 13.

- Sugár 1984, p. 72.

- Sugár 1984, p. 73.

- Szarka 2018, pp. 46–47.

Sources

Primary sources

- Bak, János M., "Online Decreta Regni Mediaevalis Hungariae. The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary" (2019). All Complete Monographs. 4. Central European University.

Secondary sources

- Csizmadia, Andor (1981). "Urbárium és közigazgatás a feudális kori Apátfalván [Urbarium and Administration in Apátfalva during the Age of Feudalism]". In Román, János (ed.). Borsodi levéltári évkönyv 4 (in Hungarian). Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén megyei Levéltár. pp. 9–48. ISSN 0134-1847.

- Markó, László (2006). A magyar állam főméltóságai Szent Istvántól napjainkig: Életrajzi Lexikon [Great Officers of State in Hungary from King Saint Stephen to Our Days: A Biographical Encyclopedia] (in Hungarian). Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963-208-970-7.

- Nógrády, Árpád (1995). ""Magistratus et comitatus tenetibus". II. András kormányzati rendszerének kérdéséhez ["Magistratus et comitatus tenetibus". To the Question of Andrew II's System of Government]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 129 (1): 157–194. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Sugár, István (1984). Az egri püspökök története [The History of the Bishops of Eger] (in Hungarian). Szent István Társulat. ISBN 963-360-392-7.

- Szarka, János (2018). "Görög rítusú egri püspökség az Árpád-korban [The Greek Rite Bishopric of Eger in the Árpádian Age]". Miskolci Keresztény Szemle (in Hungarian). Keresztény Értelmiségiek Szövetsége. 14 (1): 42–55. ISSN 2676-8127.

- Zsoldos, Attila (2011). Magyarország világi archontológiája, 1000–1301 [Secular Archontology of Hungary, 1000–1301] (in Hungarian). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. ISBN 978-963-9627-38-3.