Philadelphia City Hall

Philadelphia City Hall is the seat of the municipal government of the City of Philadelphia in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. Built in the ornate Second Empire style, City Hall houses the chambers of the Philadelphia City Council and the offices of the Mayor of Philadelphia.[6][7]

| Philadelphia City Hall | |

|---|---|

North face of Philadelphia City Hall in July 2019 | |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1894 to 1908[I] | |

| Preceded by | Ulm Minster |

| Surpassed by | Singer Building |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Architectural style | Second Empire |

| Location | 1 Penn Square Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°57′8.62″N 75°9′48.95″W |

| Topped-out | 1894[1] occupied from 1877[1][2][3] |

| Completed | 1901[1] |

| Governing body | Jim Kenney, Mayor of Philadelphia (2016-present) |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 548 ft (167 m)[1] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 9[4] |

| Floor area | 630,000 sq ft (59,000 m2)[5] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | John McArthur Jr. Thomas U. Walter |

| Designated | December 16, 1976 |

| Reference no. | 75001206 |

| Designated | December 8, 1976 |

| Reference no. | 76001666 |

This building is also a courthouse, serving as the seat of the First Judicial District of Pennsylvania. It houses the Civil Trial and Orphans' Court Divisions of the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County.[8][9][10]

Built using brick, white marble and limestone, Philadelphia City Hall is the world's largest free-standing masonry building and was the world's tallest habitable building upon its completion in 1894. It was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1976; in 2006, it was also named a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.[11]

History and description

The building was designed by Scottish-born architect John McArthur Jr. and Thomas Ustick Walter[12] in the Second Empire style, and was constructed from 1871 to 1901 at a cost of $24 million. City Hall's tower was completed by 1894,[1] although the interior was not finished until 1901. Designed to be the world's tallest building, it was surpassed during construction by the Washington Monument, the Eiffel Tower and the Mole Antonelliana. The Mole Antonelliana was a few feet taller and was the tallest masonry (i.e. without the use of steel) building in the world until 1953. In that year a storm caused the spire to collapse and Philadelphia City Hall became the tallest masonry building in the world (obviously if you don't consider monuments, such as the Washington Monument, as buildings). Upon completion of its tower in 1894, it became the world's tallest habitable building.[2][3] It was also the first secular building to have this distinction, as all previous world's tallest buildings were religious structures, including European cathedrals and—for the previous 3,800 years—the Great Pyramid of Giza; even the Mole Antonelliana was supposed to be a religious building - a synagogue - but then received a different use.

The location chosen was one of the five center city urban park squares dedicated by William Penn, that geometrically is the center to the other four squares within Center City renamed as Penn Square. City Hall is a masonry building whose weight is borne by granite and brick walls up to 22 ft (6.7 m) thick. The principal exterior materials are limestone, granite, and marble. The original design called for virtually no sculpture. The stonemason William Struthers and sculptor Alexander Milne Calder were responsible for the more than 250 sculptures, capturing artists, educators, and engineers who embodied American ideals and contributed to this country's genius.[13] The final construction cost was $24 million.

At 548 ft (167 m), including the statue of city founder William Penn atop its tower, City Hall was the tallest habitable building in the world from 1894 to 1908. It remained the tallest in Pennsylvania until it was surpassed in 1932 by the Gulf Tower in Pittsburgh; it is now the 16th tallest. It was the tallest in Philadelphia until 1986 when the construction of One Liberty Place surpassed it,[14] ending the informal gentlemen's agreement that had limited the height of buildings in the city to no higher than the Penn statue.[15]

It was constructed over the time span from 1871 to 1901 and includes 700 rooms dedicated for uses of various governmental operations. The building structure used over 88 million bricks and thousands of tons of marble and granite.[16] With almost 700 rooms, City Hall is the largest municipal building in the United States and one of the largest in the world.[17] The building houses three branches of government: the city's executive branch (the Mayor's Office), its legislature (the Philadelphia City Council), and a substantial portion of the judicial activity in the city (the Civil Division and Orphan's Court of the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas for the First Judicial District are housed there, as well as chambers for some criminal judges and some judges of the Philadelphia Municipal Court).

It was the tallest clock tower in the world when it was completed; it was surpassed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower in 1912, and is currently the 5th tallest building of this type. The tower features a clock face on each side that is 26 ft (7.9 m) in diameter.[18][19] The clock faces are larger in diameter than those on Big Ben which measure 23 ft (7 m).[20] City Hall's clock was designed by Warren Johnson and built in 1898.[21] The 1937 Philadelphia Guide noted that "shortly after the clock was installed the city inaugurated a custom which still continues. Every evening at three minutes of nine the tower lights are turned off, and then turned on again on the hour. This enables those within observation distance, though unable to see the hands, to set their timepieces.[22] There are four bronze eagles, each weighing three tons with 12 ft (3.7 m) wingspans, perched above the tower's four clocks.[16]

City Hall's observation deck is located directly below the base of the statue, about 500 ft (150 m) above street level.[23] Once enclosed with chain-link fencing, the observation deck is now enclosed by glass. It is reached in a 6-person elevator whose glass panels allow visitors to see the interior of the iron superstructure that caps the tower and supports the statuary and clocks. Stairs within the tower are only used for emergency exit. The ornamentation of the tower has been simplified; the huge garlands that festooned the top panels of the tower were removed.

In the 1950s, the city council investigated tearing down City Hall for a new building elsewhere. They found that the demolition would have bankrupted the city due to the building's masonry construction.

Beginning in 1992, Philadelphia City Hall underwent a comprehensive exterior restoration, planned and supervised by the Historical Preservation Studio of Vitetta Architects & Engineers, headed by renowned historical preservation architect Hyman Myers.[24] The majority of the restoration was completed by 2007, although some work has continued, including the installation of four new ornamental courtyard gates, based on an original architectural sketch, in December 2015.[25][26][27]

The building was voted 21st on the American Institute of Architects' list of Americans' 150 favorite U.S. structures in 2007.[28]

William Penn statue

_p11_STATUE_OF_WILLIAM_PENN.jpg.webp)

The building is topped by a 37 ft (11 m) bronze statue weighing 53,348 lb (24,198 kg)[1] of city founder William Penn, one of 250 sculptures created by Alexander Milne Calder that adorn the building inside and out. The statue was cast at the Tacony Iron Works of Northeast Philadelphia and hoisted to the top of the tower in fourteen sections in 1894.[1] The statue is the tallest atop any building in the world.[1][29][30]

Despite its lofty perch, the city has mandated that the statue be cleaned about every ten years to remove corrosion and reduce deterioration due to weathering, with the latest cleaning done in May 2017.[29] Penn's statue is hollow, and a narrow access tunnel through it leads to a 22-inch-diameter (56 cm) hatch atop the hat.[31]

Calder wished the statue to face south so that its face would be lit by the sun most of the day, the better to reveal the details of his work. The statue actually faces northeast, towards Penn Treaty Park in the Fishtown section of the city, which commemorates the site where Penn signed a treaty with the local Native American tribe.[32] Pennsbury Manor, Penn's country home in Bucks County, is also located to the northeast.

By the terms of a gentlemen's agreement that forbade any structure from rising above the hat on the Penn statue, Philadelphia City Hall remained the tallest building in the city until it was surpassed by One Liberty Place in 1986.[14][15] The abrogation of this agreement supposedly brought a curse onto local professional sports teams.[33] Twice during the 1990s, the statue was partially clothed in a major league sports team's uniform when they were in contention for a championship: a Phillies cap in 1993 and a Flyers jersey in 1997—both teams lost.[34] The supposed curse ended 22 years later when the Phillies won the 2008 World Series, a year and four months after a Penn statuette had been affixed to the final beam of the Comcast Center during its topping out ceremony in June 2007.[35] Another Penn statuette was placed on the topmost beam of the Comcast Technology Center in November 2017,[36] and the Eagles won the Super Bowl a few months later.[37]

Centre Square

City Hall is situated on land that was reserved as a public square upon the city's founding in 1682. Originally known as Centre Square—later renamed Penn Square[38]—it was used for public gatherings until the construction of City Hall began in 1871. Centre Square was one of the five original squares of Philadelphia laid out on the city grid by William Penn. The square had been located at the geographic center of Penn's city plan, but the Act of Consolidation in 1854 created the much larger and coterminous city and county of Philadelphia.[39] Though no longer at the exact center of the city, the square remains situated in the center of the historic area between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers; an area which is now called Center City.

Penn had intended that Centre Square be the central focus point where the major public buildings would be located, including those for government, religion, and education, as well as the central marketplace. However, the Delaware riverfront would remain the de facto economic and social heart of the city for more than a century.[40][41]

Film appearances

City Hall has been a filming location for several motion pictures including Rocky (1976), Blow Out (1981), Trading Places (1983), Philadelphia (1993), 12 Monkeys (1995), National Treasure (2004), Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009), and Limitless (2011).[42]

Gallery

City Hall's Dilworth Plaza at Christmas in 2005

City Hall's Dilworth Plaza at Christmas in 2005 The North Broad Street arcade

The North Broad Street arcade The north façade from Broad Street

The north façade from Broad Street View from City Hall's courtyard

View from City Hall's courtyard.jpg.webp) The William Penn statue that sits atop City Hall

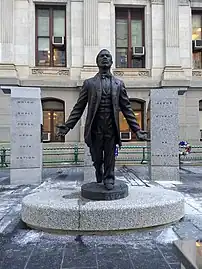

The William Penn statue that sits atop City Hall Statue of President McKinley

Statue of President McKinley

See also

- List of state and county courthouses in Pennsylvania

- List of tallest buildings in Pennsylvania

- List of tallest buildings in Philadelphia

- List of tallest clock towers

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Center City, Philadelphia

- Parliament Building, Quebec City - built at approximately the same time in the same style

Note

- I The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (an authority on the official height of tall buildings worldwide) provides the following criteria for defining the completion of a building: "topped out structurally and architecturally, fully-clad, and open for business, or at least partially occupiable."[43] Philadelphia City Hall was occupied by the mayor beginning in 1889[2] and the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania beginning in 1891,[3] and the building was topped out in 1894.[1] City Hall was the tallest habitable building in the world until 1908 when surpassed by the Singer Building. City Hall was surpassed during its construction by the Washington Monument and the Eiffel Tower, and is slightly lower by about 0.5 m (1 ft 8 in) than the Mole Antonelliana (completed in 1889);[44][45] however, none of those three structures are considered habitable buildings.

References

Notes

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form". (archive) National Park Service. pp. 2, 10. Retrieved November 9, 2017. "The tower rising 548 feet, City Hall was the highest occupied building in America…Construction lasted for thirty years (1872-1901); the building was occupied in stages over a period of twenty-two years (1877-1898)…The statue was…hoisted to the top of the tower in fourteen sections in 1894."

- ""History of City Hall: 1886-1890". (archive) Retrieved November 9, 2017. "1889: Mayor Fitler moves into completed offices on west side."

- "History of City Hall: 1891-1901". (archive) Retrieved November 9, 2017. "1891: State Supreme Court opens in permanent courtroom."

- "City Hall virtual tour room directory" Archived August 5, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. phila.gov. City of Philadelphia. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- "Philadelphia City Hall". Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2016. Technical specs of City Hall

- "Visit City Council". Philadelphia City Council. January 6, 2021. Archived from the original on May 1, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

All Philadelphia City Council Stated Meetings and hearings take place in Council Chambers, located on the fourth floor of Philadelphia City Hall.

- "Office of the Mayor". phila.gov. City of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Homepage". Philadelphia Courts. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Court of Common Pleas, Trial Division - Civil". Philadelphia Courts. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "The Court of Common Pleas, Orphans' Court Division". Philadelphia Courts. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- "Philadelphia City Hall Named as Historic Landmark". ASCE Philadelphia Section. May 22, 2006. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- "National Register Digital Assets - Philadelphia City Hall" Archived December 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. nps.gov. National Park Service. December 8, 1976. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Marin, Max (June 14, 2021). "'Nothing left uncarved': A guide to the 250 sculptures on Philadelphia City Hall". Billy Penn. Archived from the original on May 7, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- "Billy Penn no Longer the High Spot". The Philadelphia Inquirer. September 11, 1986. pp. B01.

- Gerber, Benjamin M. (2006). ""No-Law" Urban Height Restrictions: A Philadelphia Story". The Urban Lawyer. 38 (1): 111–161. ISSN 0042-0905. JSTOR 27895609.

- "Philadelphia City Hall". www.emporis.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- "Philadelphia City Hall, Philadelphia". Emporis. 2011. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- "City Hall Virtual Tour". phila.gov. City of Philadelphia. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- "City Hall: Trivia & Fun Facts: The Tower: The Clock (four faces)". Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

Note: click the 'Trivia & Fun Facts' link at left, then the 'Tower' link at top.

- "Big Ben:The Clock Dials" Archived May 21, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. parliament.uk. Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- "The Clock Business 1903m - Construction begins on great floral clock for 1904 World’s Fair" Archived March 10, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. wsjsociety.com. The Warren Johnson Society. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- Federal Writers' Project (1937). Philadelphia: A Guide to the Nation's Birthplace. The American Guide Series. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Telegraph Press. p. 380.

- "City Hall Virtual Tour". www.phila.gov. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- Fish, Larry (April 15, 1999). "City Hall Sets Up Eight-year Plan To Clean Up Its Act $130 Million Project To Restore Building's Luster". philly.com. Philadelphia Media Network (Digital), LLC. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Adams, Jennifer (2012). "Reviving A National Landmark". Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Marsh, Bill (July 25, 2006). "People Stop Fighting Philadelphia City Hall". www.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Harris, Linda K. (September 9, 2015). "First of Four Monumental Portal Gates Installed at City Hall". centercityphila.org. Center City District | Central Philadelphia Development Corporation | Center City District Foundation. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Other Philadelphia buildings on the list included the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Fisher Fine Arts Library at the University of Pennsylvania, 30th Street Station, and Wanamaker's department store."America's Favorite Architecture" Archived April 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. (February 9, 2005). American Institute of Architects. Retrieved April 23, 2014

- Trinacria, Joe (May 17, 2017). "William Penn Is Getting a Facelift" (archive). phillymag.com. Philadelphia Magazine. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "William Penn Statue - A Bronze Sculpture, Over 37 Feet High and 53,000 Pounds". www.enjoyingphiladelphia.com. 2017. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- "William Penn Statue". (archive) Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- Hornblum, Allen M. (2003). Philadelphia's City Hall. Arcadia Publishing. p. 63.

- Destra, Brooke (May 13, 2020). "Look Back at the Curse of Billy Penn and When Part of Philly Sports Lore Began". NBC10 Philadelphia. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- Witmer, Ann (April 26, 2013). "Philadelphia's City Hall Tower offers a stunning 500-foot view: Not far by car" Archived December 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. pennlive.com. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- Matza, Michael (October 22, 2008). "Lifting the curse of William Penn". philly.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- Lattanzio, Vince (November 30, 2017). "The Comcast Technology Center Is Philly's Tallest Building and Yes, There's a Mini Billy Penn Up There". NBC10 Philadelphia. NBCUniversal Media, LLC. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- Bergman, Jeremy (February 4, 2018). "Eagles QB Nick Foles wins Super Bowl LII MVP". National Football League. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- "Philadelphia City Hall location" Archived November 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. philadelphiabuildings.org. The Athenaeum of Philadelphia. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "Philadelphia Parks – William Penn Historic Philadelphia Squares Oases". fishtownonline. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015.

- Weigley, RF; et al. (1982). Philadelphia: A 300-Year History. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-01610-2.

…hardly anyone lived west of Fourth Street before 1703 … Not until the mid-nineteenth century … was the Schuylkill waterfront fully developed. Nor was Centre Square restored as the heart of Philadelphia until the construction of City Hall began in 1871.

- "Centre Square: The heart of Philadelphia" (archive). by John Kopp. May 8, 2017. phillyvoice.com. Philly Voice - WWB Holdings, LLC. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- "Filmed in Philadelphia: 25 movies that give Philly locations a silver screen spotlight". www.pennlive.com. March 21, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "CTBUH Height Criteria: Building Status - Complete" (archive.org). ctbuh.org. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Mole Antonelliana" Archived July 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. museocinema.it. Museo Nazionale del Cinema. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

- "Mole Antonelliana" Archived June 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. emporis.com. Emporis Gmbh. Retrieved November 12, 2017.

Further reading

- Gurney, George, Sculpture of a City—Philadelphia's Treasures in Bronze and Stone, Fairmount Park Association, Walker Publishing Co., Inc., New York, NY, 1974.

- Hayes, Margaret Calder, Three Alexander Calders: A Family Memoir by Margaret Calder Hayes, Paul S. Eriksson, publisher, Middlebury, Vermont, 1977.

- Lewis, Michael J. "‘Silent, Weird, Beautiful’: Philadelphia City Hall," Nineteenth Century, vol. 11, nos. 3 and 4 (1992), pp. 13–21

External links

- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-1530, "Philadelphia City Hall", 58 photos, 23 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- HABS No. PA-6771, "Philadelphia City Hall", 1 photo, 4 color transparencies, 1 photo caption page

- "Philadelphia City Hall". SkyscraperPage.

- Official Hand Book, City Hall, Philadelphia – handbook by City Publishing Co. (1901)

- Google Street View