Circles of Sustainability

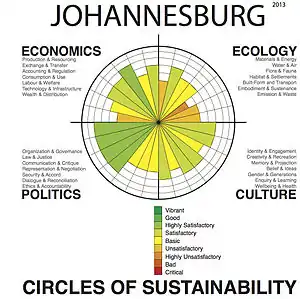

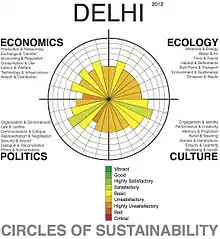

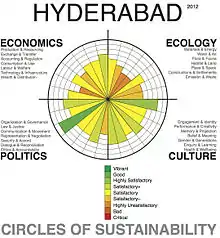

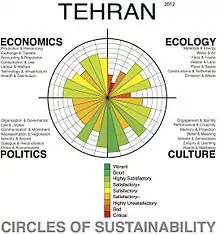

Circles of Sustainability is a method for understanding and assessing sustainability, and for project management directed towards socially sustainable outcomes.[1] It is intended to handle 'seemingly intractable problems'[2] such as outlined in sustainable development debates. The method is mostly used for cities and urban settlements.

.jpg.webp)

The style of the charts themselves could be described as a mixture of radar chart and bar chart.

Outline

Circles of Sustainability, and its treatment of the social domains of ecology, economics, politics and culture, provides the empirical dimension of an approach called 'engaged theory'. Developing Circles of Sustainability is part of larger project called 'Circles of Social Life', using the same four-domain model to analyze questions of resilience, adaptation, security, reconciliation. It is also being used in relation to thematics such as 'Circles of Child Wellbeing' (with World Vision).

As evidenced by Rio+20 and the UN Habitat World Urban Forum in Napoli (2012) and Medellin (2014), sustainability assessment is on the global agenda.[3] However, the more complex the problems, the less useful current sustainability assessment tools seem to be for assessing across different domains: economics, ecology, politics and culture.[4] For example, the Triple Bottom Line approach tends to take the economy as its primary point of focus with the domain of the environmental as the key externality. Secondly, the one-dimensional quantitative basis of many such methods means that they have limited purchase on complex qualitative issues. Thirdly, the size, scope and sheer number of indicators included within many such methods means that they are often unwieldy and resist effective implementation. Fourthly, the restricted focus of current indicator sets means that they do not work across different organizational and social settings—corporations and other institutions, cities, and communities.[5] Most indicator approaches, such as the Global Reporting Initiative or ISO14031, have been limited to large corporate organizations with easily definable legal and economic boundaries. Circles of Sustainability was developed to respond to those limitations.

History

The method began with a fundamental dissatisfaction with current approaches to sustainability and sustainable development, which tended to treat economics as the core domain and ecology as an externality. Two concurrent developments provided impetus: a major project in Porto Alegre, and a United Nations’ paper called Accounting for Sustainability, Briefing Paper, No. 1, 2008. The researchers developed a method and an integrated set of tools for assessing and monitoring issues of sustainability while providing guidance for project development.[6] The method was then further refined through projects in Melbourne and Milwaukee, and through an ARC-funded cross-disciplinary project[7] that partnered with various organizations including Microsoft Australia, Fuji Xerox Australia, the City of Melbourne, World Vision, UN-Habitat and most crucially Metropolis.[8] In Canada, the Green Score City Index[9] was inspired by studying the UN Circles of Sustainability. However, unlike this system, the Canadian index data-sets are focused on measuring the physical footprints of human activity and greenspace footprints which are less subjectivity than cultural and economic[10] indicators.

Use of the method

The method is used by a number of cities across the world, and was at different times central to the work of a series of global organizations including the United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme, The World Association of Major Metropolises,[11] and World Vision to support their engagement in cities. Cities that have used the Circles method in different ways to manage major projects or to provide feedback on their sustainability profiles include the following: Berlin, Broadmeadows, Christchurch, Hobart, Hyderabad, Johannesburg, Maryborough, Melbourne, New Delhi, Punta Arenas, São Paulo, and Tehran. It is a method for understanding urban politics and urban planning, as well as for conducting sustainability analysis and profiling sustainable development.

Global Compact Cities Programme

The methodology was made available by UN Global Compact Cities Programme from 2009-2014 for its engagement with its more than 80 Signatory Cities. In particular, some of the 14 Innovating Cities in the programme have influenced the development of the Circles of Sustainability method through their management of major projects, some with intensity and others as a background feature. They use a cross-sectoral and holistic approach for developing a response to self-defined problems.[12]

Porto Alegre, Vila Chocolatão project

The Vila Chocolatão project refers to the 2011 resettlement of approximately 1,000 residents of the inner-city Vila Chocolatão slum in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The resettlement project of Vila Chocolatão commenced in 2000 in response to an imminent eviction of the community, with community members seeking resources and support to resettle through the city of Porto Alegre's renown participatory budgeting system. The lengthy preparation to resettle was led by a local cross-sectoral network group, the Vila Chocolatão Sustainability Network. The group was initially instigated by the Regional Court, TRF4 and consisted of the Vila Chocolatão Residents Association, local government departments, federal agencies, non-government organisations and the corporate sector. The project was supported by the City of Porto Alegre through the municipality’s Local Solidarity Governance Scheme. In 2006, the Vila Chocolatao resettlement project was recognised as a pilot project for the then new Cities Programme model with City Hall assembling a Critical Reference Group to identify critical issues and joint solutions to those issues involved in the resettlement.

This long-standing collaborative project has been successful in rehousing a whole community of slum dwellers, it has also effected a restructuring of how the city approaches slums. The project ensured sustainability was built into the relocation through changes such as setting up of recycling depots next to existing slums and developing a formal recycling sorting facility in the new site, Residencial Nova Chocolatão, linked to the garbage-collection process of the city (an example of linking the sub-domains of ‘emission and waste’ and ‘organization and governance’); and establishing a fully resourced early childhood centre in the new community. The Vila Chocolatão Sustainability Network group continues to meet and work with the community post the resettlement. This network-led model is now being utilized by the City of Porto Alegre with other informal settlements.

Milwaukee, water sustainability project

In 2009, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, wanted to address the issue of water quality in the city.[13] The Circles of Sustainability methodology became the basis for an integrated city project. In the period of the application of the method (2009–present) there has been a rediscovery of the value of water from an industry and broader community perspective.[14]

In 2011, Milwaukee won the United States Water Prize given by the Clean Water America Alliance,[15] as well as a prize from IBM Better Cities program worth $500,000. The community has also attracted some leading water treatment innovators and is establishing a graduate School of Freshwater Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.[16]

Metropolis (World Association of the Major Metropolises)

The methodology was first used by Metropolis for Commission 2, 2012, Managing Urban Growth. This Commission, which met across the period 2009–2011, was asked to make recommendations for use by Metropolis’s 120 member cities on the theme of managing growth. The Commission Report using the Circles of Sustainability methodology was published on the web in three languages—English, French and Spanish—and is used by member cities as a guide to practice.[17]

In 2011, the research team were invited by Metropolis to work with the Victorian Government and the Cities Programme on one of their major initiatives. The methodology was central to the approach used by the ‘Integrated Strategic Planning and Public-Private Partnerships Initiative’ organized by Metropolis, 2012–2013 for Indian, Brazilian and Iranian cities. A workshop was held in New Delhi, 26–27 July 2012, and senior planners from New Delhi, Hyderabad and Kolkata used the two of the assessment tools in the Circles of Sustainability toolbox to map the sustainability of their cities as part of developing their urban-regional plans. Other cities to use the same tools have been Tehran (in relation to their mega-projects plan) and São Paulo (in relation to their macro-metropolitan plan).[18]

From 2012 to 2014, the Cities Programme and Metropolis worked together to refine the 'Circles of Sustainability' method for use with their respective member cities. After the Cities Programme changed direction, a Metropolis Taskforce was charged with further developing the method. The method became central to work until the COVID period made international travel more difficult.

The Economist

In 2011, The Economist invited Paul James (Director of the United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme) and Chetan Vedya (Director, National Institute of Urban Affairs, India) into a debate around the question of urban sustainability and metropolitan growth. It led to over 200 letters to the editor in direct response as well as numerous linked citations on other websites.[19]

World Vision

In 2011, recognising how much the two processes of urbanization and globalization were changing the landscape of poverty, World Vision decided to shift its orientation towards urban settings. Previously 80 per cent of its projects had been in small rural communities. The Circles of Sustainability method now underpins that reorientation and pilot studies are being conducted in India, South Africa, Lebanon, Indonesia and elsewhere, to refine the methodology for aid delivery in complex urban settings.

Domains and subdomains

The Circles of Sustainability approach is explicitly critical of other domain models such as the triple bottom line that treat economics as if it is outside the social, or that treat the environment as an externality. It uses a four-domain model - economics, ecology, politics and culture. In each of these domains there are 7 subdomains.

Economics

The economic domain is defined as the practices and meanings associated with the production, use, and management of resources, where the concept of ‘resources’ is used in the broadest sense of that word.

- Production and resourcing

- Exchange and transfer

- Accounting and regulation

- Consumption and use

- Labour and welfare

- Technology and infrastructure

- Wealth and distribution

Ecology

The ecological domain is defined as the practices and meanings that occur across the intersection between the social and the natural realms, focusing on the important dimension of human engagement with and within nature, but also including the built-environment.

- Materials and energy

- Water and air

- Flora and fauna

- Habitat and settlements

- Built-form and transport

- Embodiment and sustenance

- Emission and waste

Environmental

Environmental variables measure how optimally was natural resources used, in its complete cycle. The cycle starts from identifying of source, procurement/ extraction from raw source, processing to obtain required material, production of production and waste discharge during the entire process.[20]

- Sulphur dioxide concentration

- Concentration of nitrogen oxides

- Selected priority pollutants

- Excessive nutrients

- Electricity consumption

Politics

The political is defined as the practices and meanings associated with basic issues of social power, such as organization, authorization, legitimation and regulation. The parameters of this area extend beyond the conventional sense of politics to include not only issues of public and private governance but more broadly social relations in general.

- Organization and governance

- Law and justice

- Communication and critique

- Representation and negotiation

- Security and accord

- Dialogue and reconciliation

- Ethics and accountability

Culture

The cultural domain is defined as the practices, discourses, and material expressions, which, over time, express continuities and discontinuities of social meaning.

- Identity and engagement

- Creativity and recreation

- Memory and projection

- Belief and ideas

- Gender and generations

- Enquiry and learning

- Wellbeing and health

See also

Notes

- James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315765747.

- "CITIES - The Cities Programme". citiesprogramme.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "UN-HABITAT.:. World Urban Forum 6". Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- Liam Magee, Paul James, Andy Scerri, ‘Measuring Social Sustainability: A Community-Centred Approach’, Applied Research in the Quality of Life, vol. 7, no. 3., 2012, pp. 239–61.

- Liam Magee, Andy Scerri, Paul James, Lin Padgham, James Thom, Hepu Deng, Sarah Hickmott, and Felicity Cahill, ‘Reframing Sustainability Reporting: Towards an Engaged Approach’, Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 1, 2013, pp. 225–43.

- Stephanie McCarthy, Paul James and Carolines Bayliss, eds, Sustainable Cities, Vol. 1, United Nations Global Compact, Cities Programme, New York and Melbourne, 2010, 134pp.

- ‘Semantic Technologies to Help Machines Understand Us: Fuji Xerox leads RMIT to $1.4m Grant for Real-Time Green Reports’, IT Business, 30 October 2009. Mary-Lou Considine, ‘UN-RMIT Relationship Tackles Problems in the Pacific’, Ecos Magazine, August–September 2009, p. 150.

- Andy Scerri and Paul James, ‘Communities of Citizens and “Indicators” of Sustainability’, Community Development Journal, vol. 45, no. 2, 2010, pp. 219–36. Andy Scerri and Paul James, ‘Accounting for Sustainability: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Developing ‘Indicators’ of Sustainability’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, vol. 13, no. 1, 2010, pp. 41–53. Paul James and Andy Scerri, ‘Auditing Cities through Circles of Sustainability’, Mark Amen, Noah J. Toly, Patricia L. Carney and Klaus Segbers, eds, Cities and Global Governance, Ashgate, Farnham, 2011, pp. 111–36. Andy Scerri, ‘Ends in View: The capabilities approach in ecological/sustainability economics’, Ecological Economics 77, 2012, pp. 7-10.

- "GreenScore City Index". greenscore.ca. 2014. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ‘Subjectivity in Economics’, SSRN, June 1, 2012. Matthew T. Clements, ‘Abstract: Economics cannot claim to be absolutely objective...’,St. Edward's University,

- The methodology was used by Metropolis for Commission 2, 2012, Managing Urban Growth. This Commission, which met across the period 2009–2011, was asked to make recommendations for use by Metropolis’s 120 member cities on the theme of managing growth. The Commission Report using the ‘Circles of Sustainability’ methodology was published on the web in three languages—English, French and Spanish—and is used by member cities as a guide to practice. (See http://www.metropolis.org/publications/commissions Archived 19 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- "CITIES - The Cities Programme". citiesprogramme.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Milwaukee Business Journal, 29 April 2009; John Schmid, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, 27 April 2009.

- "Milwaukee - The Cities Programme". citiesprogramme.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Clean Water America Alliance".

- "UN Global Compact | Milwaukee Water Council". thewatercouncil.com. 2012. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Publications / Commissions | Metropolis". metropolis.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Metropolis Initiative "Integrated Strategic Planning and Public Private Partnerships" meets in New Delhi | Metropolis". metropolis.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Economist Debates: Cities". economist.com. 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Borah, Michael (13 May 2018). "Sustainability measure: What is it and how do we measure it?". Medium. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

References

- Borah, Michael (13 May 2018). "Sustainability measure: What is it and how do we measure it?". Medium. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315765747.

- James, Paul; Holden, Meg; Lewin, Mary; Neilson, Lyndsay; Oakley, Christine; Truter, Art; Wilmoth, David (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Harald Mieg and Klaus Töpfer (ed.). Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development. Routledge.

- Liam Magee; Andy Scerri; Paul James; James A. Thom; Lin Padgham; Sarah Hickmott; Hepu Deng; Felicity Cahill (2013). "Reframing social sustainability reporting: Towards an engaged approach". Environment, Development and Sustainability.

- Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy (2012). "From Issues to Indicators: A Response to Grosskurth and Rotmans". Local Environment. 17 (8): 915–933. doi:10.1080/13549839.2012.714755. S2CID 153340355.

- Scerri, Andy; James, Paul (2010). "Accounting for sustainability: Combining qualitative and quantitative research in developing 'indicators' of sustainability". International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1080/13645570902864145. S2CID 145391691.

External links

- circlesofsustainability.com Circles of Sustainability website

- GreenScore.eco Green Score City Index website