Chromopertubation

Chromopertubation is a method for the study of fallopian tube patency (a state of being open or unobstructed) for suspected infertility in women caused by fallopian tube obstruction. Occlusion or pathology of the fallopian tubes is the most common cause of suspected infertility.[1] Chromopertubation is sometimes commonly referred to a "laparoscopy and dye" test.[2] It is currently one of the standard procedures in this field.[3] In most cases, chromopertubation is performed to assess and determine the cause of someone's difficulties in getting pregnant.[4]

Procedure

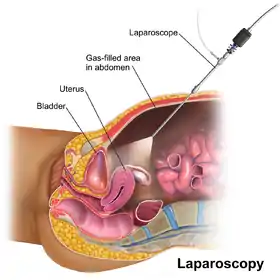

Chromopertubation is a medical procedure in which blue dye is injected into the fallopian tubes to detect if there are any blockages. It is performed as a laparoscopy, a minimally invasive procedure with small incisions. A laparoscope, a long, fine instrument is inserted into the abdomen close to the umbilicus in order to see one's internal organs, in particular the fallopian tubes. There is also a device called a uterine manipulator that is placed through the vagina and cervix into the uterus.[5] As part of a laparoscopy, a blue dye solution (methylene blue or indigo carmine) is introduced into the uterine cavity. The dye solution will help determine if the fallopian tubes are open or blocked. If the fallopian tubes are open, the dye solution will enter and drain out into the pelvic cavity through the ends of the tubes. A tubular blockage is suspected if the fluid does not enter into the fallopian tubes or enters, but does not drain out of the fallopian tubes.[5] Blocked fallopian tubes can be a factor of infertility in which the fallopian tubes will not allow the egg and sperm to meet.

Advantages

Chromopertubation with laparoscopy is considered the "gold standard" to evaluate tubal patency.[6] It is the most accurate way to look at the abdominal cavity and other pelvic structures. Other problems that can be viewed during the procedure are malformations of the uterus, adhesions, blocked fallopian tubes, or endometriosis. Slight adhesions inside a fallopian tube can be observed by the flow of dye solution and removed during the procedure.[6] Other findings, such as endometriotic lesions, may also be treated as part of laparoscopy.[6] If laparoscopy with chromopertubation shows a mild blockage within one or both of the fallopian tubes, surgical reconstruction of the tubes can be performed.[2] Studies have shown that tubal flushing with a contrast medium could be used as a treatment for infertility, as it was noted that many women were able to conceive within the first 3–6 months after the procedure.[7]

Contrast Medium

Oil-based contrast medium is typically used in hysterosalpingography (HSG), while water-based contrast medium is regularly used in hystero contrast sonography (HyCoSy), hysterosalpingo-foam sonography (HyFoSy), laparoscopy with chromopertubation, and HSG.[8] A meta-analysis that combined the results of five studies found that tubal flushing in HSG with an oil-based contrast medium moderately increased the odds of having a live-birth within six months.[8] The benefit of a water-soluble contrast medium in tubal flushing is unclear.[7] The effects of tubal flushing with either type of contrast media beyond six months are unknown and more research is needed to see if there is a difference in contrast media when used for tubal flushing in laparoscopy with chromopertubation.[8]

Disadvantages

Chromopertubation is done during laparoscopy, which requires general anesthesia. General anesthesia is usually safe, but problems, such as pain, nausea and vomiting, sore throat, and muscle aches may arise. Around the small incisions on the abdomen, there will be some pain and may also be some bruising around the lower abdomen.[5] There is a risk of procedural complications, such as bleeding or abdominal injury, which may result in longer recovery times.[6] Also, some bleeding in the vagina can be from the placement of the instrument during the dye test. Minor bleeds should stop within a couple of days.[5] Another issue is the chance of cornual spasms, which often occur if the injection of dye is done too quickly.[1] These spasms, or contractions, can block off the interstitial region (proximal portion) of the fallopian tubes, leading to an incorrect diagnosis of proximal tube occlusion.[1] Furthermore, the insertion of the instruments into the abdomen can potentially injure major abdominal organs, such as the small and large intestines, bladder, and blood vessels. Previous surgeries or procedures, such as Caesarean surgery, ovarian cyst removal, bladder surgery, or appendix removal can increase the chances of abdominal organs damage during chromopertubation. Difficulties with the insertion of the laparoscope can rarely happen. These difficulties usually occur in those who are overweight or who have had previous abdomen scarring from another procedure. If the instrument cannot be inserted into the abdominal cavity, chromopertubation will not be recommended. Instead, alternative methods of checking the fallopian tubes will be taken into consideration. Because laparoscopy with chromopertubation is a more time intensive diagnostic procedure, if no significant findings are found, then there may be a delay in starting other infertility therapies.[6]

Methylene blue dye

Allergic-like reactions and methemoglobinemia have been documented after the use of methylene blue dye in chromopertubation.[9] These reported symptoms vary from blue discoloration of body fluids to anaphylactic shock.[10] Methemoglobinemia is a blood disorder that can potentially result in various levels of cyanosis.[11] High levels of methylene blue dye can also result in hemolysis. In particular, methylene blue dye should be avoided in people using serotonergic drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and antidepressants, since this interaction may cause fatal serotonergic syndrome.[12] Serotonergic syndrome presents as changes in mental status, in addition to overactivation of the neuromuscular and nervous systems.[13] Common symptoms of fatal serotonergic syndrome include high fevers, seizures, and tremors.[14] Other reported features of fatal serotonergic syndrome include hyperthermia, respiratory failure, rhabdomyolysis, metabolic acidosis, myoglobinuria, renal failure, coma, and death.[13]

Oil-based contrast medium

While there have been recent studies showing an increased odds of clinical pregnancy when an oil-based contrast medium is used for tubal flushing, there is also an increased risk for intravasation.[15] Intravasation of oil-based contrast is the process of small oil droplets entering the blood circulation and causing inflammation of blood vessels or blocking blood vessels, potentially in the lungs or brain.[15] Oil-based contrast medium also has a higher amount of iodine, as compared to water-based contrast medium, and this higher iodine exposure could lead to subclinical hypothyroidism.[15]

Cost of procedure

The cost of fallopian tube surgeries can range from $3,000 to up to about $13,000.[16] The costs of the procedures and surgeries depends on insurance coverage, complications, and the type of fallopian tube surgery. In the female reproductive system, the fallopian tubes are one of the most important parts because the tubes connect to the ovaries where the eggs are released. To check if the fallopian tubes are blocked or damaged, a laparoscopy will cost from $1,700 to $5,000.[17] If the fallopian tubes are blocked, there will be no fertilization and therefore, the egg and sperm cannot meet. If an individual wants to open up their fallopian tubes, a procedure called fallopian tube recanalization can be performed. During this procedure, cuts or incisions are not necessary, instead a catheter is inserted into the womb and fallopian tubes to make sure a blockage is confirmed, and then a second catheter is inserted to clear that blockage. This can cost about $3,000–$5,000.[16] In addition, there is another procedure called salpingostomy when the fallopian tubes are filled with fluid. This procedure costs about $5,000–$7,000. The doctor opens the tube to remove the blockage, but does not disturb the position of the fallopian tube.[16]

Alternatives

There are also other procedures to determine whether or not someone's fallopian tubes are blocked. While laparoscopy with chromopertubation is considered to be the first-line practice for the diagnosis of tubal occlusion, it is generally a more expensive and invasive procedure, and it is recommended for women with comorbidities of both tubal occlusion and another pelvic pathology.[18]

Hysterosalpingography

Hysterosalpingography (HSG), a different diagnostic procedure for tubal occlusion, is commonly performed in women without suspected comorbidities.[18] HSG is done initially with an X-ray examination performed by a radiologist. While the main purpose of HSG is to evaluate the fallopian tubes, HSG does not provide an explanation for why the tubes are blocked. The examination should be scheduled between 7–12 days of an individual's menstrual cycle.[19] Ideally, it should be completed within 2–5 days after menses is over.[1] Radiographic dye is used to assess the uterine cavity and fallopian tubes. It can be used to study suspected infertility, as well as tubal disease.[20] During a HSG procedure, the uterus is injected with contrast dye, which can be observed via fluoroscopy.[21] The test results are normal if the X-ray shows a normal uterine shape, and the dye spills out from the ends of the fallopian tubes. There may be a problem if the dye shows an abnormally shaped uterus, and the dye does not flow freely from the fallopian tubes.[19] While this method can be completed relatively quickly since anesthesia is not needed, there is a risk of tubal spasm, which typically occurs during injection of the contrast dye due to increased pressure.[20] With tubal spasm, the fallopian tubes can close, and this may give a false diagnosis of tubal occlusion.[20] While both HSG and chromopertubation can cause spasms, it is more likely to happen with HSG.[1] HSG also has the disadvantage of exposing the patient to radiation from the X-ray that is performed.[2] The radiographic dye, which is iodine-based, can also cause allergic reactions.[22] Though this generally does not occur, there is an increased risk of genital tract infections so patients may be prescribed antibiotics.

Sonohysterosalpingography

Sonohysterosalpingography (SHG), a type of ultrasound exam, is another procedure that assesses patency through the use of varying contrast medium. One method is to introduce air into the uterine cavity and observe air bubbles in the fallopian tubes.[11] The second method is to use distilled water or normal saline to observe the movement of fluid through the tubes.[23] Here, fluid enters the uterus through the cervix via a plastic tube.[24] The last method involves combining air with saline to make it easier to see on ultrasound.[23] Images of the uterus lining are created through the use of sound waves, and the fluid introduced into the uterus serves to enhance the images.[24] Side effects of this exam include cramping and a rare possibility of pelvic infection.[24] Generally this procedure can be done quickly since no sedation is required and it tends to be a cheaper alternative compared to the other methods.[1]

Hystero contrast sonography

Hystero contrast sonography (HyCoSy) is another alternative to chromopertubation that allows for visualization of the uterine cavity, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. However, it is generally used as a screening test to assess the need for laparoscopy.[22] The procedure includes an initial vaginal scan, with a subsequent injection of contrast agent via an intrauterine catheter. The contrast agent is taken up by the fallopian tubes.[22] Since HyCoSy is performed using transvaginal ultrasound, it is less invasive than chromopertubation. Using a contrast agent, the ultrasound image can be used to detect whether and how the contrast medium flows through the fallopian tubes. The contrast medium used is often a manufactured product with microbubbles or a gel-based product that creates foam when passing through the tubes.[23] While the contrast medium is generally safe, there can still be allergic reactions as well as adverse effects.[22] A positive result is recorded when contrast is not observed to pass through the fallopian tubes. In this case, laparoscopy can be considered as the next step to verify the diagnosis of tubal occlusion.[22] This procedure does have contraindications which include reproductive tract cancer and current infections.[22] One downside is that this method tends to be more challenging to interpret so it is more accurate when done by experienced sonographers.[22]

Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy

This method is often used as an alternative to hysterosalpingography. Using this method, a Trocar along with a scope is inserted into the vagina and allows for visualization of the fallopian tubes and the uterine cavity.[25] Unlike HSG which visualizes the fallopian tubes using X-rays, transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy provides a closer look at the fallopian tubes since the scope can be threaded directly through the tubes.[25] This procedure allows clinicians the ability to look at the inner structure of the tubes. During the procedure, topical anesthesia is often given before insertion of a needle into the vagina.[25] Saline is flushed through the needle and the needle is replaced by the trocar.[25] Depending on the clinician, Lactated Ringer's may be used instead of saline.[26] Once the trocar is placed, an optic scope is inserted.[25] Upon completion of the procedure, some patients may require sutures to stop any remaining bleeding.[25] This method tends to be better for classifying tubal disease as inspection of the inner structure allows for visualization of any lesions, adhesions, and endometriomas.[26] One benefit of this procedure is that no incisions are required and it can be completed in a clinic office.[25] The disadvantages are the risk of bleeding, abdominal tenderness, and that insertion of the vaginal trocar can cause possible rectal injury.[26] When the needle is initially inserted, it is also possible for accidental perforation to the uterus wall or bowels, though this is less likely to happen.[26] While this method is extremely helpful, those with increased risk of bleeding, infections, or ovarian cysts should not undergo this procedure.[26]

Chlamydia serology

Chlamydia immunoglobulin G antibody tests (CAT) are used to explore tubal occlusions and injuries that may be caused by Chlamydia trachomatis.[1] These assays include immunofluorescence tests (including microimmunofluorescence) and ELISA.[27] While this method is noninvasive and easy to carry out, there is a chance of false-positive results. These tests can recognize antibodies to different species of Chlamydia as well as even other gram-negative bacteria.[28] Therefore, these tests are usually used as a screening test. If negative, unnecessary testing is avoided; if positive, more invasive tests are required.

Gallery

Dye visible in the fallopian tube

Dye visible in the fallopian tube Blue dye filling in the pouch of Douglas

Blue dye filling in the pouch of Douglas Blue dye exiting from fallopian tube

Blue dye exiting from fallopian tube Laparoscopy of the uterus and fallopian tubes

Laparoscopy of the uterus and fallopian tubes_(7116632365).jpg.webp) Endometriosis of the Fallopian Tube, an example of tubal occlusion

Endometriosis of the Fallopian Tube, an example of tubal occlusion

References

- Dun, Erica C.; Nezhat, Ceana H. (2012). "Tubal Factor Infertility". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 39 (4): 551–566. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2012.09.006. ISSN 0889-8545. PMID 23182560.

- Thurston, Layla; Abbara, Ali; Dhillo, Waljit S. (2019). "Investigation and management of subfertility". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 72 (9): 579–587. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205579. hdl:10044/1/71691. ISSN 0021-9746. PMID 31296604. S2CID 195892565.

- Carr BR, Blackwell RE, Azziz R (2005). Essential reproductive medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Div. ISBN 0071409939. OCLC 53955548.

- Petri, Elke; Berlit, Sebastian; Sütterlin, Marc; Hornemann, Amadeus (2013). "Chromopertubation – Presentation of a Modification of the Standard Technique". Anticancer Research. 33 (4): 1591–1594. ISSN 0250-7005. PMID 23564802.

- "Laparoscopy and Chromotubation (Dye Test) – East Sussex Healthcare NHS Trust". Archived from the original on 2021-07-29.

- Saunders, Rhiana D.; Shwayder, James M.; Nakajima, Steven T. (2011). "Current methods of tubal patency assessment". Fertility and Sterility. 95 (7): 2171–2179. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.054. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 21457959.

- Wang, Rui; Watson, Andrew; Johnson, Neil; Cheung, Karen; Fitzgerald, Cheryl; Mol, Ben Willem J; Mohiyiddeen, Lamiya (2020). "Tubal flushing for subfertility". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (10): CD003718. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003718.pub5. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 9508794. PMID 33053612. S2CID 222421134.

- Wang, R.; Welie, N. van; Rijswijk, J. van; Johnson, N. P.; Norman, R. J.; Dreyer, K.; Mijatovic, V.; Mol, B. W. (2019). "Effectiveness on fertility outcome of tubal flushing with different contrast media: systematic review and network meta-analysis". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 54 (2): 172–181. doi:10.1002/uog.20238. ISSN 1469-0705. PMID 30740799.

- Akazawa, Munetoshi; Wu, Yi-Hua; Liu, Wei-Min (2019). "Allergy-like reactions to methylene blue following laparoscopic chromopertubation: A systematic review of the literature". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 238: 58–62. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.03.019. ISSN 1872-7654. PMID 31112852. S2CID 109732178.

- Uçar, Duygy; Artunç Ülkümen, Burcu (2021). "A Rare Complication: Blue Urine Developed After Laparoscopic Chromopertubation". Forbes Journal of Medicine. 2 (1): 54–57. doi:10.5222/forbes.2021.19483.

- Rehman, Habib Ur (2001). "Methemoglobinemia". Western Journal of Medicine. 175 (3): 193–196. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.3.193. ISSN 0093-0415. PMC 1071541. PMID 11527852.

- Food and Drug Administration (2019). "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Serious CNS reactions possible when methylene blue is given to patients taking certain psychiatric medications". FDA.

- Volpi-Abadie, Jacqueline; Kaye, Adam M.; Kaye, Alan David (2013). "Serotonin syndrome". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 533–540. ISSN 1524-5012. PMC 3865832. PMID 24358002.

- Prakash, Sanjay; Rathore, Chaturbhuj; Rana, Kaushik; Prakash, Anurag (2021). "Fatal serotonin syndrome: a systematic review of 56 cases in the literature". Clinical Toxicology. 59 (2): 89–100. doi:10.1080/15563650.2020.1839662. ISSN 1556-9519. PMID 33196298. S2CID 226989100.

- Roest, Inez; Rosielle, Kimmy; Welie, Nienke van; Dreyer, Kim; Bongers, Marlies; Mijatovic, Velja; Mol, Ben W.; Koks, Carolien (2021). "Safety of oil-based contrast medium for hysterosalpingography: a systematic review". Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 42 (6): 1119–1129. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.03.014. hdl:2164/17169. ISSN 1472-6483. PMID 33931367.

- "How Much Does Fallopian Tube Surgery Cost?". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24.

- Śmigielski, Jacek A.; Piskorz, Łukasz; Koptas, Włodzimierz (2015). "Comparison of treatment costs of laparoscopic and open surgery". Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques. 10 (3): 437–441. doi:10.5114/wiitm.2015.54055. ISSN 1895-4588. PMC 4653254. PMID 26649092.

- Maheux-Lacroix, Sarah; Boutin, Amélie; Moore, Lynne; Bergeron, Marie-Ève; Bujold, Emmanuel; Laberge, Philippe Y.; Lemyre, Madeleine; Dodin, Sylvie (2013). "Hysterosalpingosonography for diagnosing tubal occlusion in subfertile women: a systematic review protocol". Systematic Reviews. 2: 50. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-2-50. ISSN 2046-4053. PMC 3703290. PMID 23826862.

- Simpson, William L.; Beitia, Laura G.; Mester, Jolinda (2006). "Hysterosalpingography: A Reemerging Study". RadioGraphics. 26 (2): 419–431. doi:10.1148/rg.262055109. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 16549607.

- Kallen, Amanda N.; Kodaman, Pinar H. (2011), "Diagnosis and Management of Tubal Factor Infertility", Infertility, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 18–25, doi:10.1002/9781444393958.ch3, ISBN 978-1-4443-9395-8

- Chalazonitis, Athanasios; Tzovara, Ioanna; Laspas, Fotios; Porfyridis, Petros; Ptohis, Nikos; Tsimitselis, Georgios (2009). "Hysterosalpingography: Technique and Applications". Current Problems in Diagnostic Radiology. 38 (5): 199–205. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2008.02.003. ISSN 0363-0188. PMID 19632497.

- Luciano, Danielle E.; Exacoustos, Caterina; Luciano, Anthony A. (2014). "Contrast Ultrasonography for Tubal Patency". Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 21 (6): 994–998. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.05.017. hdl:2108/137777. ISSN 1553-4650. PMID 24910933.

- Panchal, Sonal; Nagori, Chaitanya (2014). "Imaging techniques for assessment of tubal status". Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences. 7 (1): 2–12. doi:10.4103/0974-1208.130797. ISSN 0974-1208. PMC 4018793. PMID 24829524.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2016). "Sonohysterography". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 2021-08-02.

- Ezedinma, N. Adaobi; Phelps, John Y. (2012). "Transvaginal Hydrolaparoscopy". Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 16 (3): 461–465. doi:10.4293/108680812X13462882736295. ISSN 1086-8089. PMC 3535799. PMID 23318074.

- Gordts, S.; Puttemans, P.; Gordts, Sy.; Brosens, I.; Campo, R. (2005). "Transvaginal laparoscopy". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 19 (5): 757–767. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.06.005. ISSN 1521-6934. PMID 16087405.

- Broeze, K.A.; Opmeer, B.C.; Coppus, S.F.P.J.; Van Geloven, N.; Alves, M.F.C.; Ånestad, G.; Bhattacharya, S.; Allan, J.; Guerra-Infante, M.F.; Den Hartog, J.E.; Land, J.A. (2011). "Chlamydia antibody testing and diagnosing tubal pathology in subfertile women: an individual patient data meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (3): 301–310. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq060. ISSN 1460-2369. PMID 21227996.

- Mårdh, Per-Anders (2004). "Tubal factor infertility, with special regard to chlamydial salpingitis". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 17 (1): 49–52. doi:10.1097/00001432-200402000-00010. ISSN 0951-7375. PMID 15090891.