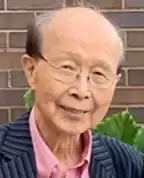

Chong-Sik Lee

Chong-Sik Lee (Korean: 이정식; July 30, 1931 – August 17, 2021) was a Korean American political scientist specializing in East Asian studies.[1]

Chong-Sik Lee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 30, 1931 |

| Died | August 17, 2021 (aged 90) |

| Awards | Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award (1974) |

| Academic background | |

| Education | |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Political scientist |

| Institutions | |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | I Jeongsik |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ri Chŏngsik |

Together with his co-author Robert A. Scalapino, he won the 1974 Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award of the American Political Science Association for the best book on government, politics or international affairs.[2]

Early life

Lee was born on July 30, 1931, in Anju, South Pyongan, Chōsen, Empire of Japan. He was the oldest son of a primary school teacher. When he was three years old, he moved to Manchuria (then Manchukuo).[3] He spent a number of years in his childhood in Manchuria, in Liaoyang and Tieling. After the liberation of Korea in 1945, his family was stranded in Liaoyang. His father went missing in March 1946, when he was 14 years old, making him the eldest male in the house. His family eventually managed to return to their hometown in 1948, which was then in North Korea.[3][4] Lee never learned what had happened to his father.[3]

Korean War

His family escaped to Seoul in South Korea in 1950. Around the outbreak of the Korean War, he began training to join the National Defense Corps (which later became involved in the National Defense Corps incident). Between 1951 and 1953, he worked in the Advanced Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ADVATIS) as a translator. Around this time, he interrogated Chinese prisoners of war.[3]

Lee had never graduated from middle school, but independently searched for learning opportunities constantly. During the war, he took classes at Shinheung College and Kyung Hee University. He was never able to graduate from either school, although Kyung Hee eventually awarded him an honorary bachelor's degree in October 2014. He later claimed that they had first offered him an honorary doctorate, which he declined it, as he already had a doctorate. Instead, he asked for the degree that he had originally wanted.[3]

Lee also had an early talent for languages. He learned Chinese and Japanese while doing odd jobs. When the Korean War broke out in June 1950, he picked up English through a mixture of practice and independent study. He improved his writing and grammar by writing diaries in English and asking American soldiers for help in revising his writing. He later wrote an article about his method for learning other languages well in 1995.[3]

His intelligence and discipline was noticed by the Americans. After the war died down, he was allowed to go to the United States in January 1954 to study.[3]

Studying in the United States

In 1954, Lee entered the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), making him one of the first Korean Americans to do so.[5] During this time, he worked as a dishwasher to earn his living expenses. He earned both a bachelor's and master's degree from the school, and was accepted into the PhD in Political Science program at the University of California, Berkeley in 1957. His knack for languages caught the attention of Robert A. Scalapino, who had been planning to write a book on communism in East Asia around that time. Together, they began extensively researching Korean and other East Asian history. After 16 years of research, they eventually published Communism in Korea in 1973, which won a Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award.[5][3] Communism in Korea was revised and reprinted as North Korea: Building of the Monolithic State in 2017.[6]

Career

Academic career

Lee joined the political science department of the University of Pennsylvania in 1963 and taught the university's first course in Korean studies. This course led to the foundation of a Korean studies department, which he actively participated in. By the time of his death, he was Emeritus Professor of Political Science.[7] He was also Eminent Scholar at Kyung Hee University, Research Professor at Korea University, and the Yongjae Chair Professor at Yonsei University.[8]

Lee’s academic career includes works about Korea’s history of communism, the division of the Korean Peninsula, and the origins of the Republic of Korea. He also researched major figures in modern Korean history such as Syngman Rhee, the first president of Korea; Lyuh Woon-hyung, a Korean politician and reunification activist in the 1940s; and Park Chung-hee, the third president of Korea, who seized power through a military coup. In particular, his works on Korea-Japan relations, communist movements in Manchuria, and the international relations of East Asia have been translated into many languages and are considered classics in East Asian studies.[3][5]

Having devoted more than five decades to collecting historical records, Lee remarked, “By reading various records, I can gain insight as to why certain events occurred, what led to the occurrence of these events, and why historical figures took particular actions.” Lee often told his students that “the true advancement of scholarship is only possible through a repetitive process of inquiry” and advised them to “accept new theories but to investigate with curiosity when these theories are unconvincing.”

He was the author of The Politics of Korean Nationalism (University of California Press, 1963)[9][10] and Kim Kyu-sik ui saengae (The Life of Kim Kyu-sik), Seoul: Shingu Munhwasa, 1974. Other books include Park Chung Hee: From Poverty to Power (KHU Press) and A 21st Century View of Post-Colonial Korea (Kyung Hee University Press). He has contributed to China Quarterly, Asian Survey, Journal of Asian Studies, Journal of International Affairs and other periodicals.[11] Lee published an autobiography in 2020 that covered his life until 1974, but "left out the rest of the stories for next time".[5]

Lee died at 9:15 am on August 17, 2021, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the age of 90,[3][8] from complications from myelodysplastic syndrome.[5]

Awards

- 2011: Kyung-Ahm Prize, Kyung-Ahm Education & Cultural Foundation[12]

- 1974: Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award of the American Political Science Association for the best book published in the United States in government, politics or international affairs[5]

References

- Erik Esselstrom (2009). Crossing Empire's Edge: Foreign Ministry Police and Japanese Expansionism in Northeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 159–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3231-5.

- "Eminent Scholar Chong-sik Lee Receives Kyung-Ahm Prize" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine. Kyung Lee University.

- 송, 화선 (2021-09-16). "식민지 조선의 '소년 가장' 세계적 석학이 되다 [卒記]" [Colonial Joseon's "Boy Head of the Household" Became a World-Class Scholar]. 신동아 (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Lee, Chong-Sik (2012). Park Chung-Hee: From Poverty to Power. KHU Press. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-0-615-56028-1.

- "Chong-Sik Lee, Political Science". almanac.upenn.edu. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Geringer, Dan (29 November 2017). "Chong-sik Lee, 86, who escaped from North Korea during wartime, says earthly miracles saved his life". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- "2014 University Lecture on “Korean Thought on Independence Revisited in the 21st Century”". Kyung Hee University.

- 김, 기철 (2021-08-18). "한국현대사 권위자 이정식 교수 별세" [Modern Korean History Authority Professor Lee Chong-Sik Dies]. 조선일보 (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Peter H. Lee (13 August 2013). Sourcebook of Korean Civilization: Volume Two: From the Seventeenth Century to the Modern. Columbia University Press. pp. 522–. ISBN 978-0-231-51530-6.

- Library of Congress, Federal Research Division (21 April 2011). North Korea: A Country Study. Government Printing Office. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-16-088278-4.

- James M. Minnich (2005). The North Korean People's Army: Origins and Current Tactics. Naval Institute Press. pp. 150–. ISBN 978-1-59114-525-7.

- "Eminent Scholar Chong-sik Lee Receives Kyung-Ahm Prize". www.khu.ac.kr. KYUNG HEE UNIVERSITY. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2021.