Chirocephalus diaphanus

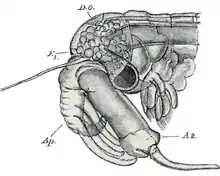

Chirocephalus diaphanus is a widely distributed European species of fairy shrimp that lives as far north as Great Britain, where it is the only surviving species of fairy shrimp and is protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. It is a translucent animal, about 0.5 in (13 mm) long, with reddened tips to the abdomen and appendages. The body comprises a head, a thorax bearing 11 pairs of appendages, and a seven-segmented abdomen. In males, the antennae are enlarged to form "frontal appendages", while females have an egg pouch at the end of the thorax.

| Chirocephalus diaphanus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female (top) & male (bottom) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Branchiopoda |

| Order: | Anostraca |

| Family: | Chirocephalidae |

| Genus: | Chirocephalus |

| Species: | C. diaphanus |

| Binomial name | |

| Chirocephalus diaphanus Prévost, 1803 | |

The life cycle of C. diaphanus is extremely fast, and the species can only persist in pools without predators. The eggs tolerate drying out, and hatch when re-immersed in water. C. diaphanus was first reported in the scientific literature in 1704, but was only separated from other species and given its scientific name in 1803. The specific epithet diaphanus refers to the animal's transparency.

Description

Chirocephalus diaphanus is a "beautiful, translucent crustacean".[1] Its body is subcylindrical, and around 0.5 inches (13 mm) long, mostly transparent, but with black eyes, and red tips to the appendages and abdomen.[2]

The body becomes wider towards the head, which has a conspicuous mandibular groove. It also bears a pair of stalked compound eyes, as well as a sessile median eye, two pairs of antennae, and the mouthparts.[2] The mouthparts comprise a labrum, directed backwards over the mouth and pairs of mandibles, paragnatha, maxillules and vestigial maxillae.[2]

The thorax is made up of twelve body segments, the last of which is fused to the first segment of the abdomen.[2] There is no carapace,[1] but each of the eleven free segments bears a pair of phyllopodia, which have a series of bristles pointing along the animal's midline.[2] The abdomen consists of seven segments without appendages, and a slender telson which bears a pair of caudal rami.[2]

Males and females can be recognised by a suite of sexually dimorphic characters. While the antennae of females are triangular and relatively short, males' antennae are long and jointed, and each one bears a complex "frontal appendage", which is used to clasp the female during mating.[2] The last somite of the thorax is fused with the first somite of the abdomen. In males, it bears a pair of processes, the extensions of the vasa deferentia in a protrusible penis. In females, there is a single egg pouch, which is also thought to derive from a pair of appendages.[2]

Distribution

Chirocephalus diaphanus is a Mediterranean species, which reaches its north-western limit in Great Britain, and is missing from Fennoscandia.[3] Its distribution in Western Europe extends almost continuously from Great Britain to the Iberian Peninsula, and as far east as the Rhine in Germany.[4] A single occurrence of C. diaphanus is known from the Benelux countries, in pools in South Limburg, Netherlands.[5][6] Further east, it occurs south of 47°N in the Apennine and Balkan peninsulas, reaching the Black Sea in Romania; an isolated population exists at the mouth of the Vistula river in Poland.[4] In the Mediterranean Sea, populations exist on Sicily, Sardinia and Crete.[4]

C. diaphanus is the only species of fairy shrimp to occur naturally in Great Britain; Tanymastix stagnalis is found in western Ireland, and Artemia salina formerly occurred in England.[3] Within Great Britain, C. diaphanus is restricted to areas with a deficit of precipitation against evapotranspiration between April and September.[3] This means that it is only found frequently in southern England, with scattered records as far north as Yorkshire.[3]

Ecology and life cycle

The fairy shrimp is found in temporary pools of water, from seasonal ponds to muddy ruts, preferring sites with regular disturbance, such as passing tractors or livestock. It has a broad range of ecological tolerances, in terms of temperature, dissolved oxygen and pH, but cannot coexist with predatory fish.[1] C. diaphanus swims with its ventral side upwards, and is a filter feeder, collecting zooplankton and detritus with its phyllopodia.[1]

The life cycle of Chirocephalus diaphanus is extremely fast.[1] The typical duration of a full life cycle is not known, but a figure of around 3 months has been suggested.[3] The eggs are tolerant to drying out; when their habitat fills with water again, some of the eggs will hatch, while others remain dormant.[1] This enables the species to continue to survive in an unpredictable habitat, since some eggs remain in case the habitat does not persist for long enough for the animals to mate and produce offspring.[1] Dispersal between bodies of water can occur through the movements of animals such as cattle, deer and horses.[1]

Conservation status

Chirocephalus diaphanus is subject to protection under environmental law in some parts of its range. In Germany, it is included on the Red List of endangered species.[7] In the United Kingdom, C. diaphanus is protected under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, and it is listed as a "Species of Conservation Concern" under the United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan.[1] In the Isle of Man it is protected under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife Act 1990.[8] The main threat to its survival are changes in land use: its habitats are often considered unsightly, and the temporary pools it inhabits are frequently filled in or converted into permanent ponds.[1]

Taxonomic history

The first mention of any Chirocephalus species in the scientific literature was a sketch by James Petiver in a 1704 volume of his Gazophylacii Naturae, where he named it Squilla lacustris minima, dorso natante ("tiny freshwater Squilla, swimming on its back").[3] There was much confusion between species in the early literature, and it is often unclear what species early authors were referring to.[9] Carl Linnaeus, having described a fairy shrimp as a possible insect larva in Fauna Suecica, described it among the crustaceans in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae in 1758, under the name "Cancer stagnalis" (now Tanymastix stagnalis). That name was also used by later authors, but sometimes referring to other species.[9]

The situation was clarified by Bénédict Prévost in 1803, when he published a detailed description of Chirocephalus diaphanus, including mention of the frontal appendages which distinguish it from other fairy shrimp such as Tanymastix stagnalis.[9] Prévost's work was originally published in the Journal de Physique in 1803, and was reprinted by Louis Jurine as an appendix to his 1820 Histoire des Monocles, qui se trouvent aux Environs de Genève.[9]

The name Chirocephalus derives from the Greek words χείρ ("hand"), and κεφαλή ("head").[9] The specific epithet diaphanus derives from the Greek διαφανής, meaning "diaphanous" or transparent. Prévost later regretted the epithet, arguing that several other species were just as transparent as the one he had described.[10] The common name "fairy shrimp" comes from the animal's delicate appearance, and the "iridescent gleaming of the bristles on its appendages".[2]

References

- "Fairy shrimp (Chirocephalus diaphanus)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2010-06-30. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- L. A. Borradaile; F. A. Potts (1961). "Order Anostraca". The Invertebrata (4th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 370–373.

- J. H. Bratton; G. Fryer (1990). "The distribution and ecology of Chirocephalus diaphanus Prévost (Branchiopoda: Anostraca) in Britain". Journal of Natural History. 24 (4): 955–964. doi:10.1080/00222939000770601.

- Jàn Brtek; Alain Thiéry (1995). D. Belk; H. I. Dumont; G. Maier (eds.). "The geographic distribution of the European Branchiopods (Anostraca, Notostraca, Spinicaudata, Laevicaudata)". Hydrobiologia. 298 (1–3: Studies on Large Branchiopod Biology and Aquaculture II): 263–280. doi:10.1007/BF00033821. S2CID 33159433.

- L. Paulssen (2000). "De Kieuwpootkreeft Chirocephalus diaphanus (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) ontdekt in Limburg" [The fairy shrimp Chirocephalus diaphanus (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) discovered in Limburg]. Natuurhistorisch Maandblad (in Dutch). 89 (10): 226–229.

- "Resolution: Schutz des einzigen Vorkommens von Chirocephalus diaphanus in den BENELUX-Staaten in Zuid-Limburg (NL)" [Resolution: Protection of the only occurrence of Chirocephalus diaphanus in the Benelux states in South Limburg (NL)] (in German). Naturschutzbund Niederösterreich. October 14, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- Margret Binot; Rüdiger Bless; Peter Boye; Horst Gruttke; Peter Pretscher, eds. (1998). "Register". Rote Liste gefährdeter Tiere Deutschlands [German Red Data Book on Endangered Animals] (PDF). Schriftenreihe für Landschaftspflege und Naturschutz (in German). Vol. 55. Bundesamt für Naturschutz. ISBN 3-89624-110-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- "Isle of Man Government Wildlife Act 1990 : Schedule 5 : Animals which are protected" (PDF). Gov.im. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- W. Baird (1850). "Chirocephalus". A Natural History of the British Entomostraca. Ray Society. pp. 39–54. ISBN 9780384030800.

- Bénédict Prévost (1820). "Mémoire sur le Chirocéphale". In Louis Jurine (ed.). Histoire des Monocles, qui se trouvent aux Environs de Genève. Geneva: J. J. Paschoud. pp. 201–244.