Emperor of China

Huangdi (Chinese: 皇帝; pinyin: Huángdì, "Emperor") or Emperor of China was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial dynasties in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor of China was considered the Son of Heaven and the autocrat of all under Heaven worshipped posthumously under an Imperial cult. Under the Han dynasty, Confucianism gained sanction as the official political theory and succession in most cases theoretically followed agnatic primogeniture. The lineage of emperors descended from a paternal family line constituted a dynasty.

| Emperor of China | |

|---|---|

| 皇帝 | |

Imperial | |

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Style | 陛下; Bìxià; 'Your Majesty' |

| First monarch | Shi Huangdi |

| Last monarch | Mo Di Puyi |

| Formation | 221 BC, 2243–2244 years ago |

| Abolition | 12 February 1912, 111 years ago |

| Residence | Varies according to dynasties, from 1420 to 1912 in the Forbidden City in Beijing |

The absolute authority of the emperor came with a variety of governing duties and moral obligations; failure to uphold these was thought to remove the dynasty's Mandate of Heaven and to justify its overthrow. In practice, emperors sometimes avoided the strict rules of succession and dynasties' purported "failures" were detailed in official histories written by their successful replacements or even later dynasties. The power of the emperor was also limited by the imperial bureaucracy, which was staffed by scholar-officials and in some dynasties eunuchs. An emperor was also constrained by filial obligations to his ancestors' policies and dynastic traditions, such as those first detailed in the Ming dynasty's Ancestral Instructions.

Origin and history

During the Western Zhou period (c. 1046 BC – 771 BC), Chinese vassal rulers with power over their particular fiefdoms served a strong central monarch. Following a brutal succession crisis and relocation of the royal capital, the power of the Zhou kings (王, OC:*ɢʷaŋ,[2] mod. wang) waned, and during the Eastern Zhou period, the regional lords overshadowed the king and began to usurp that title for themselves. In 221 BCE, after the then-king of Qin completed the conquest of the various kingdoms of the Warring States period, he adopted a new title to reflect his prestige as a ruler greater than the rulers before him. He called himself Shi Huangdi, the First Emperor. Before this, Huang (皇, OC:*ɢʷˤaŋ, "august, sovereign") was most commonly seen as a reverential epithet for a deceased ancestor, and Di (帝, OC:*tˤeks) was an apical ancestor, originally referring to the deïfied ancestors of the Shang kings.[3][note 1] In the 3rd century BCE, the two titles had not previously been used together. The Emperor of China, like the Zhou kings before him, and the Shang kings before them, was most commonly referred to as Tianzi (天子, the Son of Heaven), who was divinely appointed to rule. The appellation Huangdi carried similar shades of meaning.[4] Alternate English translations of the word include "The August Ancestor", "The Holy Ruler", or "The Divine Lord". On that account, some modern scholars translate the title as "thearch".[3]

On occasion, the father of the ascended emperor was still alive. Such an emperor was titled the Taishang Huang (太上皇), the "Grand Imperial Sire". The practice was initiated by the First Emperor, who gave the title as a posthumous name to his own father, as was already common for monarchs of any stratum of power. Liu Bang, who established the Han dynasty, was the first to become emperor while his father yet lived. It was said he granted the title during his father's life because he would not be done obeisance to by his own father, a commoner.[5][6]

Owing to political fragmentation, over the centuries, it has not been uncommon to have numerous claimants to the title of "Son of Heaven". The Chinese political concept of the Mandate of Heaven essentially legitimized those claimants who emerged victorious. The proper list was considered those made by the official dynastic histories; the compilation of a history of the preceding dynasty was considered one of the hallmarks of legitimacy, along with symbols such as the Nine Ding or the Heirloom Seal of the Realm. As with the First Emperor, it remained very common to grant posthumous titles to the ancestors of the victors.

The Yuan and Qing dynasties were founded by successful invaders of different ethnic groups. As part of their rule over China, they also went through the culturally appropriate rituals of formally declaring a new dynasty and taking on the Chinese title of Huangdi, in addition to the titles of their respective people, especially in the case of the Yuan dynasty. Thus, Kublai Khan was simultaneously khagan of the Mongols and emperor of China.

End of the imperial system

In 1911, the title of Prime Minister of the Imperial Cabinet was created to rule alongside the emperor, as part of an attempt to turn China into a constitutional monarchy.

The Xuantong Emperor (Puyi) of the Qing dynasty was the last emperor of China, abdicated on 12 February 1912, thus ending the imperial tradition after more than 2,100 years.

Yuan Shikai, former President of the Republic of China, attempted to restore a monarchy with himself as the Hongxian Emperor, however his claim to the title of emperor ended on 22 March 1916.

Puyi was briefly restored for almost two weeks during a coup in 1917 but was overthrown again shortly after. He later became the emperor of Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state, and was captured by the Red Army as a prisoner of war after World War II and held in Chita, Soviet Union. He was returned to China and imprisoned in Fushun War Criminals Management Centre, and after he was released lived until 1967.

Had the Qing dynasty continued as an imperial house, Jin Yuzhang would currently head it. He has worked for various local councils on China, and no interest in the restoration of monarchy.[7]

Number of emperors

Traditional political theory holds that there can only be one legitimate Son of Heaven at any given time. However, identifying the "legitimate" emperor during times of division is not always uncontroversial, and therefore the exact number of legitimate emperors depends on where one stands on a number of succession disputes. The two most notable such controversies are whether Cao Wei or Shu Han was the legitimate dynasty during the Three Kingdoms, and at what point the Song dynasty ceased to be the legitimate dynasty in favor of the Yuan dynasty.[8] The Qing view, reported to Europe by the Jesuits, was that there had been 150 emperors from the First Emperor to the Kangxi Emperor.[9] Adding the eight uncontroversial emperors that followed the Kangxi Emperor would give a grand total of 158 emperors from the First Emperor to Puyi.

By one count, from the Qin dynasty to the Qing dynasty, there were a total 557 individuals who at one point or another claimed the title "emperor", several of them simultaneously.[10] Some, such as Li Zicheng, Huang Chao, and Yuan Shu, declared themselves the emperors, Son of Heaven and founded their own empires as a rival government to challenge the legitimacy of and overthrow the existing emperor. Among the most famous emperors were Qin Shi Huang of the Qin dynasty, the emperors Gaozu and Guangwu of the Han dynasty, Emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty, Kublai Khan of the Yuan dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty, and the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing dynasty.[11]

Power

The emperor's words were considered sacred edicts (simplified Chinese: 圣旨; traditional Chinese: 聖旨) and his written proclamations "directives from above" (上谕; 上諭). In theory, the emperor's orders were to be obeyed immediately. He was elevated above all commoners, nobility and members of the Imperial family. Addresses to the emperor were always to be formal and self-deprecatory, even by the closest of family members.

In practice, however, the power of the emperor varied between different emperors and different dynasties. Generally, in the Chinese dynastic cycle, emperors founding a dynasty usually consolidated the empire through absolute rule: examples include Qin Shi Huang of the Qin, Emperor Gaozu of Han, Emperor Guangwu of Han, Emperor Taizong of the Tang, Kublai Khan of the Yuan, and the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing. These emperors ruled as absolute monarchs throughout their reign, maintaining a centralized grip on the country.

The usual method for widespread geographic power consolidation was to involve the whole family. From generation to generation, the bonds weakened between the branches of family established as local rulers in different areas. After a sufficient period of time, their loyalty could no longer be assured, and the taxes they collected sapped the imperial coffers. This led to situations like the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, who disenfranchised and annihilated the nobilities of virtually all imperial relatives whose forebears had been enfeoffed by his own ancestor, Gaozu.[12]: 76–84

Apart from a few very energetic monarchs, the emperor usually delegated the majority of decision making to the civil bureaucracy (chiefly the chancellery and the Central Secretariat), the military, and in some periods the censorate. Very paranoid emperors – like Emperor Wu of Han and the Hongwu Emperor of Ming – would cycle through high government officials with alarming frequency, or simply leave top-ranking posts vacant, such that no one could threaten their power. During other reigns, certain officials in the civil bureaucracy wield more powerful than the emperor himself.[13]

The emperor's position, unless deposed in a rebellion, was always hereditary, usually by agnatic primogeniture. As a result, many emperors ascended the throne while still children. During minority reigns, the Empress Dowager (i.e., the emperor's mother) would usually possess significant political power, along with the male members of her birth family. In fact, the vast majority of female rulers throughout Chinese Imperial history came to power by ruling as regents on behalf of their sons; prominent examples include the Empress Lü of the Han dynasty, as well as Empress Dowager Cixi and Empress Dowager Ci'an of the Qing dynasty, who for a time ruled jointly as co-regents. Where Empresses Dowager were too weak to assume power, or her family too strongly opposed, court officials often seized control. Court eunuchs had a significant role in the power structure, as emperors often relied on a few of them as confidants, which gave them access to many court documents. In a few places, eunuchs wielded vast power; one of the most powerful eunuchs in Chinese history was Wei Zhongxian during the Ming dynasty. Occasionally, other nobles seized power as regents.

The actual area ruled by the Emperor of China varied from dynasty to dynasty. In some cases, such as during the Southern Song dynasty, political power in East Asia was effectively split among several governments; nonetheless, the political fiction that there was but one ruler was maintained.

Heredity and succession

The title of emperor was hereditary, traditionally passed on from father to son in each dynasty. There are also instances where the throne is assumed by a younger brother, should the deceased emperor have no male offspring. By convention in most dynasties, the eldest son born to the Empress consort (嫡长子; 嫡長子) succeeded to the throne. In some cases when the empress did not bear any children, the emperor would have a child with another of his many wives (all children of the emperor were said also to be the children of the empress, regardless of birth mother). In some dynasties the succession of the empress' eldest son was disputed, and because many emperors had large numbers of progeny, there were wars of succession between rival sons. In an attempt to resolve after-death disputes, the emperor, while still living, often designated a Crown Prince (太子). Even such a clear designation, however, was often thwarted by jealousy and distrust, whether it was the crown prince plotting against the emperor, or brothers plotting against each other. Some emperors, like the Yongzheng Emperor, after abolishing the position of Crown Prince, placed the succession papers in a sealed box, only to be opened and announced after his death.

Unlike, for example, the Japanese monarchy, Chinese political theory allowed for a change in the ruling house. This was based on the concept of the "Mandate of Heaven". The theory behind this was that the Chinese emperor acted as the "Son of Heaven" and held a mandate to rule over everyone else in the world; but only as long as he served the people well. If the quality of rule became questionable because of repeated natural disasters such as flood or famine, or for other reasons, then rebellion was justified. This important concept legitimized the dynastic cycle or the change of dynasties.

This principle made it possible even for peasants to found new dynasties, as happened with the Han and Ming dynasties, and for the establishment of conquest dynasties such as the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty and Manchu-led Qing dynasty. It was moral integrity and benevolent leadership that determined the holder of the "Mandate of Heaven".

There has been only one lawful female reigning emperor in China, Empress Zetian, who briefly replaced the Tang dynasty with her own Zhou dynasty. Many women, however, did become de facto leaders, usually as Empress Dowager. Prominent examples include Empress Dowager Lü of the Han dynasty, Empress Dowager Liu of the Sung dynasty and Empress Dowager Cixi of the Qing dynasty.

Styles, names and forms of address

- To see naming conventions in detail, please refer to Chinese sovereign

As the emperor had, by law, an absolute position not to be challenged by anyone else, his or her subjects were to show the utmost respect in his or her presence, whether in direct conversation or otherwise. When approaching the Imperial throne, one was expected to kowtow before the emperor. In a conversation with the emperor, it was considered a crime to compare oneself to the emperor in any way. It was taboo to refer to the emperor by his or her given name, even for the emperor's own mother, who instead was to use Huángdì (皇帝), or simply Ér (儿; 兒, "son", for male emperor). The given names of all the emperor's deceased male ancestors were forbidden from being written, and could be avoided (避諱) by using synonymous characters, homophonous characters, or simply leaving out the final stroke of the tabboo word. This linguistic feature can sometimes be used to date historical texts, by noting which words in parallel texts are altered.

The emperor was never to be addressed as "you". Anyone who spoke to the emperor was to address him or her as Bìxià (陛下, lit. the "Bottom of the Steps"), corresponding to "Your Imperial Majesty"; Huángshàng (皇上, lit. Radiant Highness); Shèngshàng (圣上; 聖上, lit. Holy Highness); or Tiānzǐ (天子, lit. "Son of Heaven"). The emperor could also be alluded to indirectly through reference to the imperial dragon symbology. Servants often addressed the emperor as Wànsuìyé (万岁爷; 萬歲爺, lit. Lord of Ten Thousand Years). The emperor referred to himself or herself as zhèn (朕), the original Chinese first-person singular arrogated by the First Emperor, functioning as an equivalent to the "Royal We", or, self-deprecatingly, Guǎrén (寡人, the "Morally-Deficient One", from the longer [Guǎdé zhī rén] 寡德之人) or Gū (孤, the "Lonely One", from the longer [Gūjiā] 孤家) in front of his or her subjects.

In contrast to the Western convention of referring to a sovereign using a regnal name (e.g. George V) or by a personal name (e.g. Queen Victoria), a governing emperor was to be referred to simply as Huángdì Bìxià (皇帝陛下, Majesty|His/Her Majesty the Emperor) or Dāngjīn Huángshàng (当今皇上; 當今皇上, The Present Emperor Above) when spoken about in the third person. Under the Qing, the emperor was usually styled His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of the Great Qing Dynasty, Son of Heaven, Lord of Ten Thousand Years although this varied considerably. In historical texts, the present emperor was referred to almost universally as Shang (上; "Above").

Generally, emperors also ruled with an era name (年号; 年號). Since the adoption of era names by Emperor Wu of Han and up until the Ming dynasty, the sovereign conventionally changed the era name semi-regularly during his or her reign. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, emperors simply chose one era name for their entire reign, and people often referred to past emperors with that title. In earlier dynasties, the emperors were known with a temple name (庙号; 廟號) given after their death. Most emperors were also given a posthumous name (谥号; 謚號, Shìhào), which was sometimes combined with the temple name (e.g. Emperor Shèngzǔ Rén 圣祖仁皇帝; 聖祖仁皇帝 for the Kangxi Emperor). The passing of an emperor was referred to as Jiàbēng (驾崩; 駕崩, lit. "collapse of the [imperial] chariot") and an emperor that had just died was referred to as Dàixíng Huángdì (大行皇帝), literally "the Emperor of the Great Journey."

Consorts and children

The imperial family was made up of the emperor and the empress (皇后) as the primary consort and Mother of the Nation (国母; 國母). In addition, the emperor would typically have several other consorts and concubines (嫔妃; 嬪妃), ranked by importance into a harem, in which the Empress was supreme. Every dynasty had its set of rules regarding the numerical composition of the harem. During the Qing dynasty, for example, imperial convention dictated that at any given time there should be one Empress, one Huang Guifei, two Guifei, four fei and six pin, plus an unlimited number of other consorts and concubines. Although the emperor had the highest status by law, by tradition and precedent the mother of the emperor, i.e., the empress dowager (皇太后), usually received the greatest respect in the palace and was the decision maker in most family affairs. At times, especially when a young emperor was on the throne, she was the de facto ruler. The emperor's children, the princes (皇子) and princesses (公主), were often referred to by their order of birth, e.g., Eldest Prince, Third Princess, etc. The princes were often given titles of peerage once they reached adulthood. The emperor's brothers and uncles served in court by law, and held equal status with other court officials (子). The emperor was always elevated above all others despite any chronological or generational superiority.

Ethnicity

Recent scholarship is wary of applying present-day ethnic categories to historical situations. Most Chinese emperors have been considered members of the Han ethnicity, but there were also many Chinese emperors who were of non-Han ethnic origins. The most successful of these were the Khitans (Liao dynasty), Jurchens (Jin dynasty), Mongols (Yuan dynasty), and Manchus (Qing dynasty). The orthodox historical view sees these as dynasties as sinicized polities as they adopted Han culture, claimed the Mandate of Heaven, and performed the traditional imperial obligations such as annual sacrifices to Heaven (as Tian or Shangdi) for rain and prosperity. The revisionist New Qing History school, however, argues that the interaction between politics and ethnicity was far more complex and that elements of these dynasties differed from and altered "native Chinese" traditions concerning imperial rule.[14]

Gallery

Early dynasties and Qin

Han and Three Kingdoms

Emperor Gaozu of Han (256 –195 BC)

Emperor Gaozu of Han (256 –195 BC) Emperor Wen of Han (202 –157 BC)

Emperor Wen of Han (202 –157 BC) Emperor Jing of Han (188 BC –141 BC)

Emperor Jing of Han (188 BC –141 BC) Emperor Wu of Han (156 –87 BC)

Emperor Wu of Han (156 –87 BC) Emperor Zhao of Han (94 –74 BC)

Emperor Zhao of Han (94 –74 BC) Emperor Xuan of Han (91 –49 BC)

Emperor Xuan of Han (91 –49 BC) Emperor Yuan of Han (75 –33 BC)

Emperor Yuan of Han (75 –33 BC) Emperor Cheng of Han (51 –7 BC)

Emperor Cheng of Han (51 –7 BC) Emperor Ai of Han (27 –1BC)

Emperor Ai of Han (27 –1BC) Emperor Guangwu of Han (5 BC–57 AD)

Emperor Guangwu of Han (5 BC–57 AD) Emperor Ming of Han (28– 7 5AD)

Emperor Ming of Han (28– 7 5AD) Emperor Zhang of Han (56– 88)

Emperor Zhang of Han (56– 88) Emperor Xian of Han (181–234)

Emperor Xian of Han (181–234) Emperor Wen of Wei (187–226)

Emperor Wen of Wei (187–226) Emperor Da of Eastern Wu (182–252)

Emperor Da of Eastern Wu (182–252) Emperor Zhaolie of Shu Han (162–223)

Emperor Zhaolie of Shu Han (162–223)

Jin and Northern and Southern dynasties

Emperor Wu of Jin (236–290)

Emperor Wu of Jin (236–290)

Emperor Wu of Liu Song (363–422)

Emperor Wu of Liu Song (363–422) Emperor Gao of Southern Qi (427–482)

Emperor Gao of Southern Qi (427–482) Emperor Wu of Liang (464–549)

Emperor Wu of Liang (464–549) Emperor Wu of Chen (503–559)

Emperor Wu of Chen (503–559) Emperor Xuan of Chen (530–582)

Emperor Xuan of Chen (530–582) Emperor Wen of Chen (522–566)

Emperor Wen of Chen (522–566) Emperor Fei of Chen (554–570)

Emperor Fei of Chen (554–570) Emperor Houzhu of Chen (553–604)

Emperor Houzhu of Chen (553–604).jpg.webp) Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi (526–559)

Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi (526–559) Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou (543–578)

Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou (543–578)

Sui dynasty

Emperor Wen of Sui (541–604)

Emperor Wen of Sui (541–604) Emperor Yang of Sui (569–618)

Emperor Yang of Sui (569–618)

Tang dynasty

Emperor Gaozu of Tang (566–635)

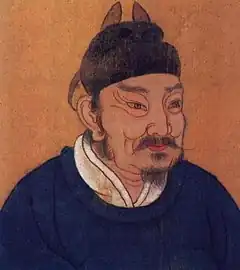

Emperor Gaozu of Tang (566–635) Emperor Taizong of Tang (598–649)

Emperor Taizong of Tang (598–649) Emperor Gaozong of Tang (628–683)

Emperor Gaozong of Tang (628–683) Empress Wu Zetian of the Zhou dynasty (690–705)

Empress Wu Zetian of the Zhou dynasty (690–705) Emperor Zhongzong of Tang (656–710)

Emperor Zhongzong of Tang (656–710) Emperor Ruizong of Tang (662–716)

Emperor Ruizong of Tang (662–716) Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685–762)

Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685–762) Emperor Shengwu of Yan (703-757)

Emperor Shengwu of Yan (703-757) Emperor Suzong of Tang (711–762)

Emperor Suzong of Tang (711–762) Emperor Daizong of Tang (727–779)

Emperor Daizong of Tang (727–779) Emperor Dezong of Tang (742–805)

Emperor Dezong of Tang (742–805) Emperor Xianzong of Tang (778–820)

Emperor Xianzong of Tang (778–820) Emperor Muzong of Tang (795–824)

Emperor Muzong of Tang (795–824)_(cropped).jpg.webp) Emperor Jingzong of Tang (809-827)

Emperor Jingzong of Tang (809-827) Emperor Wenzong of Tang (809–840)

Emperor Wenzong of Tang (809–840) Emperor Wuzong of Tang (814–846)

Emperor Wuzong of Tang (814–846) Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (810–859)

Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (810–859) Emperor Yizong of Tang (833–873)

Emperor Yizong of Tang (833–873) Emperor Xizong of Tang (862–888)

Emperor Xizong of Tang (862–888) Emperor Zhaozong of Tang (867–904)

Emperor Zhaozong of Tang (867–904)

Five dynasties

Northern Song dynasty

.jpg.webp) Zhao Hongyin, posthumously made emperor by his son, the first emperor of the Song dynasty

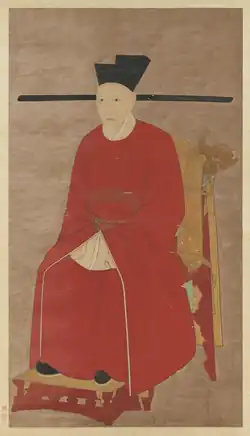

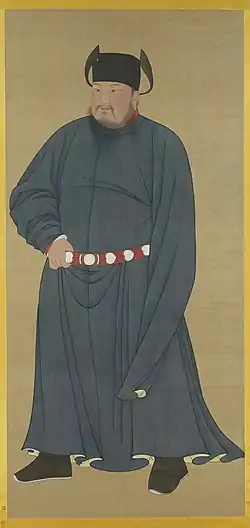

Zhao Hongyin, posthumously made emperor by his son, the first emperor of the Song dynasty Emperor Taizu of Song (927–976)

Emperor Taizu of Song (927–976) Emperor Taizong of Song (939–997)

Emperor Taizong of Song (939–997) Emperor Zhenzong of Song (968–1022)

Emperor Zhenzong of Song (968–1022) Emperor Renzong of Song (1010–1063)

Emperor Renzong of Song (1010–1063) Emperor Yingzong of Song (1032–1067)

Emperor Yingzong of Song (1032–1067) Emperor Shenzong of Song (1048–1085)

Emperor Shenzong of Song (1048–1085) Emperor Zhezong of Song (1077–1100)

Emperor Zhezong of Song (1077–1100) Emperor Huizong of Song (1082–1135)

Emperor Huizong of Song (1082–1135) Emperor Qinzong of Song (1100–1161)

Emperor Qinzong of Song (1100–1161)

Southern Song dynasty

Emperor Gaozong of Song (1104–1187)

Emperor Gaozong of Song (1104–1187) Emperor Xiaozong of Song (1127–1194)

Emperor Xiaozong of Song (1127–1194) Emperor Guangzong of Song (1147–1200)

Emperor Guangzong of Song (1147–1200) Emperor Ningzong of Song (1168–1224)

Emperor Ningzong of Song (1168–1224) Emperor Lizong of Song (1205–1264)

Emperor Lizong of Song (1205–1264) Emperor Duzong of Song (1240–1274)

Emperor Duzong of Song (1240–1274) Emperor Gong of Song (1271–1323)

Emperor Gong of Song (1271–1323) Emperor Duanzong (1270–1278)

Emperor Duanzong (1270–1278) Zhao Bing (1272–1279)

Zhao Bing (1272–1279)

Yuan dynasty

Kublai Khan (1215–1294)

Kublai Khan (1215–1294) Temür Khan (1265–1307)

Temür Khan (1265–1307) Külüg Khan (1281–1311)

Külüg Khan (1281–1311) Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan (1285–1320)

Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan (1285–1320) Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür (1304–1332)

Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür (1304–1332) Rinchinbal Khan (1326–1332)

Rinchinbal Khan (1326–1332)

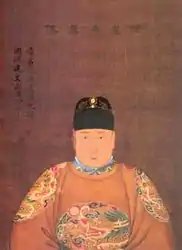

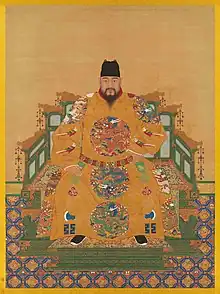

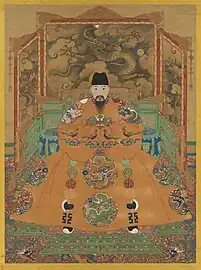

Ming dynasty

Qing dynasty

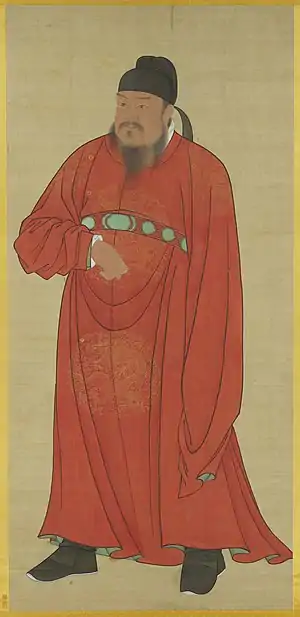

Yuan Shikai as the Hongxian Emperor of China (1915–1916)

Yuan Shikai as the Hongxian Emperor of China (1915–1916)

See also

- Chinese emperors family tree

- Tributary system of China

- List of Chinese monarchs

- Dragon Throne

- Taishang Huang, an honorific for a retired emperor

- Tian (Heaven) / Shangdi (God)

- Monarchy of China

- Dynasties in Chinese history

- Emperor at home, king abroad

Notes

- Huang (皇) and Di (帝) were also terms applied to the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors, mythical godly rulers and culture heroes credited with feats like ordering the sky and forming the first humans out of clay, as well as the invention of agriculture, clothing, astrology, music, etc.

References

- Dillon, Michael, ed. (2017). Encyclopedia of Chinese History. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-415-42699-2.

- Baxter, William & al. Baxter–Sagart Old Chinese Reconstruction Archived September 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. 2011. Accessed 22 Dec 2013.

- Nadeau, Randall L. The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Chinese Religions, pp. 54 ff. John Wiley & Sons (Chichester), 2012. Accessed 22 December 2013.

- Harrison, Thomas; Blanshard, Alastair; Bryce, Trevor; Coningham, Robin; Jenner, W. J. F.; Kaizer, Ted; Llewellen-Jones, Lloyd; Manley, Bill; Manuel, Mark; et al. (Authors) (2009). Harrison, Thomas (ed.). The Great Empires of the Ancient World. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-89236-987-4.

- Sima Qian, Records of the Grand Historian, "Gaozu's Basic Annals", 61

- Sima Qian (author) & Burton Watson (translator) (1971). Records of the Grand Historian of China "Volume I: The Early Years of the Han dynasty from 209 to 141 B.C. Part III: The Victor - The Basic Annals of Emperor Kao-tsu (Shih-chi 8)" p. 108-109.

- "Just call me Jin, says the man who would be emperor". Sydney Morning Herald. Nine Entertainment. 27 November 2004. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- Wilkinson, Endymion. (2018). Chinese History, a New Manual. Pp 9-8, 684

- Intorcetta, Prospero. (1687). Confucius Sinarum Philosophus

- Barmé, Geremie (2008). The Forbidden City. Harvard University Press. p. 594. ISBN 978-0-674-02779-4.

- "看版圖學中國歷史", p.5, Publisher: Chung Hwa Book Company, Year: 2006, Author: 陸運高, ISBN 962-8885-12-X.

- Nylan, Michael (2016). "Mapping Time in the Shiji and Hanshu Tables". East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine. Brill (43): 61–122. doi:10.1163/26669323-04301004. JSTOR 90006244. S2CID 171943719.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985). A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 4–102. ISBN 9789576382857.

- Sinicization vs. Manchuness: The Success of Manchu Rule

Further reading

- Paludan, Ann (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05090-2.

.jpg.webp)