Chesterfield Railroad

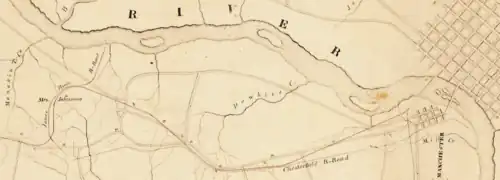

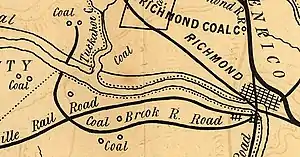

The Chesterfield Railroad was located in Chesterfield County, Virginia. It was a 13-mile (21-kilometer) long mule-and-gravity powered line that connected the Midlothian coal mines with wharves that were located at the head of navigation on the James River just below the Fall Line at Manchester (on the south bank directly across from Richmond). It began operating in 1831 as Virginia's first common carrier railroad.[1]

| Chesterfield Railroad | |

|---|---|

1837 map of the line | |

| Overview | |

| Status | Closed |

| Owner | Chesterfield Railroad Company |

| Locale | Chesterfield County, Virginia |

| Termini |

|

| Service | |

| Type | long mule-and-gravity powered |

| Operator(s) | Chesterfield Railroad Company |

| History | |

| Opened | July 1, 1831 |

| Closed | 1851 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 13 mi (21 km) |

| Number of tracks | 1 |

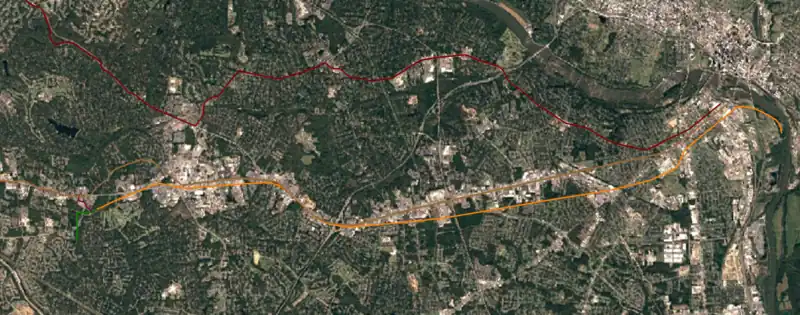

Although it was dismantled before the American Civil War after being supplanted by the steam-powered Richmond and Danville Railroad, several portions of the embankments for the roadbed are extant in Chesterfield County near present-day Midlothian Turnpike.

History

Coal mining in the Midlothian area of Chesterfield County began in the 18th century. Around 1701, French Huguenot settlers to the area discovered the existence of the coalfield. The coalfield was part of the Richmond Basin which is one of the Eastern North America Rift Basins which contains some sedimentary rock and bituminous coal. In a 1709 diary entry William Byrd II, who is credited as the founder of Richmond, and had purchased 344 acres (139 ha) of land in the area where coal was found, noted that "the coaler found the coal mine very good and sufficient to furnish several generations." It was first commercially mined in the 1730s, and was used to make cannon at Westham (near the present Huguenot Memorial Bridge) during the American Revolutionary War.[2]

In 1804, the Manchester and Falling Creek Turnpike was built to ease traffic on what is now Old Buckingham Road. In 1807, became the first graveled roadway of any length in Virginia.[2] However, by 1824, Midlothian area coal mine owners were frustrated by the difficulty of transporting on the toll road, now known as Midlothian Turnpike, more than 1,000,000 bushels of coal by wagons and horse teams to waiting ships below the falls at Manchester on the banks of the James River.

Seeking a better method of transportation so that their markets could be expanded, in 1825, a group of mine owners, including Nicholas Mills, Beverly Randolph and Abraham S. Wooldridge, resolved to build a tramway. The Wooldridge family hailed from East Lothian and West Lothian in Scotland, and named their mining company Mid-Lothian, the source of the modern name.

Planning and construction 1827-1831

In the winter of 1827, Claudius Crozet, Virginia's State Engineer, surveyed the proposed route and deemed it feasible for construction. This feasibility study was necessary to obtain funding assistance from the Virginia Board of Public Works, a state agency which, beginning in 1816, invested in a portion of the stock of privately managed companies building canals, turnpikes, and, later, railroads.[3][4]

In February 1828, the Chesterfield Railroad Company obtained its charter from the Virginia General Assembly. Within a year, $100,000 stock was subscribed, half purchased by the colliers of Chesterfield County and half by Richmond-area investors. The company hired Moncure Robinson, (1802–1891) a European-trained engineer and U.S. railroad pioneer to supervise construction.

In 1830, capital stock was increased to $150,000 to cover unexpectedly high construction expenses. By June 1831, the construction was completed at $127,000 total cost.

Most profitable railroad in the world 1831-1850

By September, 1831, the railroad was operational, using horses, mules and gravity as motive power. One hundred and sixty cars were put into operation, and it was an instant financial success.

In 1836, the Chesterfield Railroad Company reported carrying 25,903 cars, 84,976 tons (77,089 tonnes) of coal. It received gross revenues of $83,409. This equaled 19% of stockholders' original investment repaid plus 6% dividend. It was reputed to be the most profitable railroad in the world at the time.

In 1840, one of the mining companies reported that 300,000 bushels of coal were extracted from the 777-foot (237 m)-deep Pump Shaft alone, one of the more active mines, using the labor of approximately 150 men and 25 mules.[5] It is believed that most of this coal was shipped out by the Chesterfield Railroad.

By 1844, the Chesterfield Railroad had repaid the stockholders' entire original investment and consequently came under regulation of Virginia Board of Public Works, which adjusted charges to fix a dividend return of 6%. The rate for carrying coal reduced from 6¢ per bushel to 3¢.

Outmoded by steam railroad competition 1850-1851

.jpg.webp)

In 1850, the new steam-driven Richmond and Danville Railroad began operation to Coalfield Station (later renamed Midlothian). Although unsuccessful lawsuits followed, the Chesterfield Railroad was quickly supplanted by the competition. It filed its last report with the Virginia Board of Public Works in 1851. With permission from the state legislature, the Chesterfield Railroad was dismantled before the American Civil War.[5]

Design features

Operating its entire lifetime without any locomotives, Chesterfield Railroads moved its railcars loaded with coal mostly by gravity downhill to the docks on the James River at the southern edge of Manchester. In places where the line ran uphill, mules helped the cars climb some slopes. The empty cars were hauled back uphill by the mules to the mine, to be reloaded again. In one area the weight of the loaded cars and their downhill motion pulled the empty cars (connected to the full ones by ropes and drums) back toward the mines.

One of the most remarkable features was a cycloidal inclined plane, a drum and rope device by which loaded coal-carrying cars lowered down the steep western slope of Falling Creek Valley pulled by two empty cars traveling up the slope. On the eastern side, the loaded cars were then raised 80 feet (24 m) over a 1,000-foot (300 m) distance, with power supplied by animals. After completing that movement, the roadbed was mostly a gradual downhill slope over relatively level terrain towards Manchester.

Revenues

Presidents

- Nicholas Mills

- George Fisher (1843)[9]

Heritage & remnants

The Chesterfield Railroad is commemorated by two Virginia Historical Markers and an exhibit in the Chesterfield County Museum, located near the court house. In addition, various portions of the road bed still exist today.

Gallery

- Remnants of the Chesterfield Railroad

The now damaged granite block eastern and western abutments that were part of the Falling Creek Railroad Bridge of the Chesterfield Railroad.

The now damaged granite block eastern and western abutments that were part of the Falling Creek Railroad Bridge of the Chesterfield Railroad. This is the railroad bridge of the Chesterfield Railroad over Pocoshock Creek in Chesterfield County, Virginia.

This is the railroad bridge of the Chesterfield Railroad over Pocoshock Creek in Chesterfield County, Virginia. This is the railroad bed, looking West, of the Chesterfield Railroad over Pocoshock Creek in Chesterfield County, Virginia.

This is the railroad bed, looking West, of the Chesterfield Railroad over Pocoshock Creek in Chesterfield County, Virginia.

First Railroad in Virginia Historical marker & remnant site nearby

Historical marker |VA-S30, is located on U.S. Route 60, at Pocoshock Creek, 3.78 miles (6.08 km) west of the Richmond city limits at State Route 150, and 1.5 miles (2.41 km) west of the junctions of US Highway 60 and State Route 76.

At this location, a short portion of the former rail bed on a fill is still visible just south of the marker, between a retail center and a condominium complex.

Chesterfield Railroad Virginia Historical marker & remnant site nearby

Historical marker |VA-O64 is located about 2 miles (3.2 km) east of the Village of Midlothian in U.S. Route 60.

Just 1 mile (1.6 km) west of this marker, the site of the cycloidal inclined plane on the steep western slope of Falling Creek Valley is still recognizable and juxtaposes the remains of the railroad bridge at Falling Creek. The location is about 1-mile (1.6 km) east of the Village of Midlothian on U.S. Route 60.

Chesterfield County Museum

An exhibit on local mining history in the Chesterfield Museum includes a length of iron rail from the incline railway, first in Virginia.

Extant Remnants

After its discontinuation in 1851, the Chesterfield Railroad roadbed was used as a trail or road for various sections and as a property boundary. In the 20th century, Richmond greatly expanded and much of the old roadbed has been demolished to make way for new developments. Some sections still remain:

- The first half mile before terminating in the Stonehenge Village shopping center

- A tenth of a mile from Alverser Drive to the Jaguar car dealership

- A quarter of a mile centering on Pocoshock Creek

- A few long sections around Chippenham Parkway

Furthermore, some sections of the spur lines exist: a twentieth of a mile section of the spur to the Chesterfield Coal and Iron Mining Company (formerly known locally as the "English" company) southeast of the intersection of Walton Park Road and Walton Park Lane and a few sections of the Midlothian company spur, which the Richmond and Danville Railroad used as the southern part of its Midlothian spur.

Notes

- "Railroad Historical Almanac 1820 - 1839" (PDF). Almanac. The National Railway Historical Society (NRHS). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "Coal Mining in Chesterfield, VA". GreatCPA. David B. Robinson. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "Board of Public Works Introduction" (PDF). Librarian of Virginia. p. 1. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Pawlett, Nathaniel Mason. "A Brief History of the Roads of Virginia 1607-1840". National Transportation Library. U.S. Department of Transportation. p. 21. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- "Mid-Lothian Mines and Railroad Foundation - Midlothian, Virginia". Mid-Lothian Mines Park. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- Twenty-eighth Annual Report of the Board of Public Works to the General Assembly of Virginia. Richmond, Va.: Samuel Shepherd. 1843. pp. 161, 162. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Thirty-third Annual Report of the Board of Public Works to the General Assembly of Virginia. Richmond, Va.: Samuel Shepherd. 1848. pp. 336, 337. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Annual Reports of Officers, Boards, and Institutions of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Richmond, Va.: William F. Ritchie. 1849. pp. 224–226. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Annual Report of the Board of Public Works to the General Assembly of Virginia. Richmond, Va.: Samuel Shepherd. 1843. p. 161, 162. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

Further reading

- Thomas F. Garner, Jr., editor, Historically Significant Sites on the Mid-Lothian Coal Mining Co. Tract In Chesterfield County, Virginia, a collection of articles and excerpts

- Coleman, Elizabeth Dabney (1954) Forerunner of Virginia's First Railway by Virginia Caval-cade Magazine, Volume IV, Number 3, page 7. Virginia State Library: Winter issue, 1954.

- Scarburgh, George Parker, (1850), Opinion of Honorable George P. Scarburgh, of Accomac, Virginia, in the cases between the Chesterfield Railroad Company and the Richmond and Danville Railroad Company Richmond, VA: H. K. Ellyson

- Gamst, Frederick C. (1990) The Ingenious Railroad on Falling Creek, Virginia's First article in: The Messenger Chesterfield Courthouse, VA (October 1990 issue . No.18, p. 1, 4-9)

- James, George Watson (1967), Gravity plus mules equal "steam." in: Virginia Record Richmond, VA. (April 1967 issue v.89, no.4, p. 8)

- McCartney, Martha W., (1989) Historical Overview Of The Midlothian Coal Mining Company Tract - Chesterfield County, Virginia

External links

- Chesterfield County Virginia official website, Historic Chesterfield page

- Chesterfield Railway Chronology

- Trains From Yesterday: The Bicentennial story of Southern Railway*Virginia Places: Coal Transportation pages

- Midlothian Mines and Rail Road Foundation

- Old Dominion Railway Museum, Richmond, VA

- Virginia Department of Historic Resources, Highway Marker official website

- Coal Mining in Chesterfield County, Virginia website

- Virginia Historical Society

- Chesterfield Historical Society

- Trains From Yesterday: The Bicentennial story of Southern Railway