Chemical communication in insects

Chemical communication in insects is social signalling between insects of the same or different species, using chemicals. These chemicals may be volatile, to be detected at a distance by other insects' sense of smell, or non-volatile, to be detected on an insect's cuticle by other insects' sense of taste. Many of these chemicals are pheromones, acting like hormones outside the body.

Among the many functions of chemical communication are attracting mates, aggregating conspecific individuals of both sexes, deterring other individuals from approaching, announcing a new food source, marking a trail, recognizing nest-mates, marking territory and triggering aggression.

History of research

In 1965, the entomologist Edward O. Wilson published a paper on chemical communication in the social insects, arguing that their societies were principally organised by "complex systems of chemical signals".[1] By 1990, Mahmoud Ali and David Morgan noted that the field had grown too large to review comprehensively.[2]

Semiochemicals

In addition to the use of means such as making sounds, generating light, and touch for communication, a wide range of insects have evolved chemical signals, semiochemicals. Types of semiochemicals include pheromones and kairomones. Chemoreception is the physiological response of a sense organ to a chemical stimulus where the chemicals act as signals to regulate the state or activity of a cell.[2][3]

Semiochemicals are often derived from plant metabolites. Pheromones, a type of semiochemical, are used for attracting mates, for aggregating conspecific individuals of both sexes, for deterring other individuals from approaching, to mark a trail, and to trigger aggression in nearby individuals. Allomones benefit their producer by the effect they have upon the receiver. Kairomones benefit their receiver instead of their producer. Synomones benefit the producer and the receiver. While some chemicals are targeted at individuals of the same species, others are used for communication across species. The use of scents is especially well-developed in social insects.[3] Cuticular hydrocarbons are nonstructural materials produced and secreted to the cuticle surface to fight desiccation and pathogens. They are important, too, as pheromones, especially in social insects.[4]

Pheromones

Pheromones are of two main kinds: primer pheromones, which generate a long-duration change in the insect that receives them, or releaser pheromones, which cause an immediate change in behaviour.[2] Primers include the queen pheromones essential to maintain the caste structure of social Hymenopteran colonies; they tend to be non-volatile and are dispersed by workers across the colony.[5] In some ants and wasps, the queen pheromones are cuticular hydrocarbons.[6]

| Type | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Bring sexes together for mating | Well-studied in Lepidoptera |

| Invitation | Stimulate feeding or oviposition at a site | |

| Aggregation | Bring individuals together | Temporarily in sub-social insects; permanently in social insects |

| Dispersal or spacing | Reduce intraspecific competition for a scarce resource | |

| Alarm | Signal attack or alarm | Mostly in colonial insects |

| Trail | Mark a line on a surface as a path to be followed | Mainly in Hymenoptera (e.g. ants) and Isoptera (termites); a few Lepidoptera (e.g. processionary moths) |

| Territorial and home range | Mark a territory or range | |

| Surface and funeral | Dead ants stimulate their removal from the nest. | Possibly assist in recognition of colony or species |

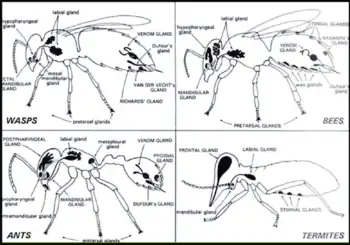

Eusocial insects including ants, termites, bees, and social wasps produce pheromones from several types of exocrine gland. These include mandibular glands in the head, and Dufour's, tergal, and other glands in the abdomen.[5]

Human uses of pheromones

Human uses of pheromones include their application instead of insecticides in orchards. Pest insects such as fruit moths are attracted by sex pheromones, allowing farmers to evaluate pest levels, and if need be to provide sufficient pheromone to disrupt mating.[7]

References

- Wilson, Edward O. (3 September 1965). "Chemical Communication in the Social Insects". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). 149 (3688): 1064–1071. Bibcode:1965Sci...149.1064W. doi:10.1126/science.149.3688.1064. PMID 17737837.

- Ali, Mahmoud Fadl; Morgan, E. David (1990). "Chemical communication in insect communities: a guide to insect pheromones with special emphasis on social insects". Biological Reviews. 65 (3): 227–247. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1990.tb01425.x. S2CID 86609942.

- Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2005). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1113-3.

- Yan, Hua; Liebig, Jürgen (1 April 2021). "Genetic basis of chemical communication in eusocial insects". Genes & Development. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press & The Genetics Society. 35 (7–8): 470–482. doi:10.1101/gad.346965.120. PMC 8015721. PMID 33861721.

- Hefetz, Abraham (28 March 2019). "The critical role of primer pheromones in maintaining insect sociality". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 74 (9–10): 221–231. doi:10.1515/znc-2018-0224. PMID 30920959.

- Yan, Hua; Liebig, Jürgen (1 April 2021). "Genetic basis of chemical communication in eusocial insects". Genes & Development. 35 (7–8): 470–482. doi:10.1101/gad.346965.120. PMC 8015721. PMID 33861721.

- "Using Pheromones Instead of Insecticides". CSIRO. Retrieved 29 June 2022.