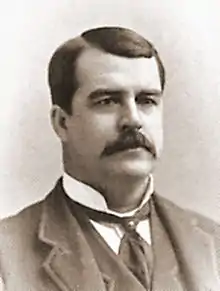

Charles Macune

Charles William Macune (May 20, 1851 – November 3, 1940) was the head of the Southern Farmers' Alliance from 1886 to December 1889 and editor of its official organ, the National Economist, until 1892. He is remembered as the father of a failed cooperative enterprise by the Farmers' Alliance in Dallas, Texas, and as the creator of the Sub-Treasury Plan, an effort to provide low-cost credit to farmers through a network of government-owned commodity warehouses.

A Democrat, Macune opposed both the formation of the People's Party as well as the nostrum of free silver which served as the basis of the 1896 fusion of the Democratic and Populist parties. Both a doctor and a lawyer in his earlier years, although he received formal training in neither profession, Macune ended his life as a Methodist minister, serving in pastorates in various towns of the Southwestern United States.

Biography

Early years

Charles William Macune was born May 20, 1851, at Kenosha, Wisconsin. His father, who worked as a blacksmith and was a Methodist minister, hailed originally from New York state; his mother was Canadian.[1] The family lived in the Midwestern states of Iowa and Illinois for over a decade before Charles' birth.[1]

In 1852 the lure of the California gold rush proved too much of a temptation for Macune's father and he went West alone to seek his fortune.[1] Instead of striking rich, the elder Macune contracted cholera and died, leaving the infant Charles to be raised alone by his mother in the town of Freeport, Illinois.[1]

Charless went to work at the age of ten for a neighboring farmer.[1] At fifteen he left the farm to become an apprentice to a pharmacist—an occupation which he found more conducive.[1] Macune left pharmacy to work a series of odd jobs, which took him to the states of Kansas and California.[1] In the summer of 1871 the 20-year-old Macune moved to what would become his home state of Texas, where he worked as a cattle drover in the northern part of the state.[1]

In September 1874 Macune entered the field of journalism for the first time, launching a weekly broadsheet in the town of Burnet called the Burnet Bulletin.[1] Macune stayed safely to the conservative "Jeffersonian" party line of the dominant Democratic Party, but his fledgling publication nonetheless succumbed to the inevitable financial pressures and was terminated in the spring of 1875.[1]

Not long after the failure of this project, Macune soon moved to San Saba, Texas, where he made money working as a house-painter while studying medicine with a local physician.[1] He moved to Junction City, Texas, by 1878 and was certified by the Texas state medical examiner as fit to practice medicine the next year.[1] Over the next several years Macune worked as a physician in several Central Texas towns, landing in Cameron, in 1881.[1]

There Macune's medical practice flourished and he began to invest in local real estate, including farm properties.[1] Macune also went together with another local doctor and purchased a local newspaper, the Cameron Herald, in 1886.[1]

Political career

Macune was active in Democratic Party politics from the middle 1870s, when he was the chairman of a county organization.[1] Macune's politics were unremarkable, as he considered him well within the Jeffersonian mainstream, based as it was upon the political equality of small-scale male property-holders and a limited vision of the role of government.

Around the time of his second newspaper purchase, Macune became involved in the politics of the Southern Farmers' Alliance. He became a charter member of the Cameron Sub-Alliance (local group) early in 1886 and was named a delegate to the Texas state convention in August of that year, where he wowed his peers and was elected Chairman of the State Executive Committee.[1] Thereafter, Macune became deeply involved in Alliance activities, seeking to rapidly expand the formation of cotton cooperatives to enable the farmers of the Alliance to produce more efficiently, with less financial loss to middlemen.[1]

Macune had a grand vision for the Farmers' Alliance, but one in which the organization served an economic and educational function rather than a political one. As head of the Executive Committee Macune was quick to stifle an impending split of the organization threatened by the desire of some Texas members to transform the Alliance into an independent political party.[2] He then moved to actively expand the organization by successfully negotiating a merger with the rival Louisiana Farmers' Union.[3] The groups were joined under a new name, the National Farmers' Alliance and Cooperative Union of America.[4] Macune remained the head of the organization through the end of 1889, at which time it claimed a membership of 1.2 million.[1]

In September 1887, Macune was instrumental in launching the Farmers' Alliance Exchange of Texas, a flagship cooperative purchasing agency for the Alliance located in Dallas.[5] The exchange attempted to boost farmers' incomes by purchasing their crop at higher prices through the removal of a layer of middlemen, as well as by reducing their costs through bulk purchases of supplies for its members.[5] Macune served as business manager of the enterprise.[5] Although Macune was opposed to the idea, the board of directors of the Exchange decided to construct a massive new four story building as substantial cost, which resulted in severe cash-flow difficulties which ultimately resulted in the Exchange's termination in December 1889.[5]

In March 1889 Macune made use of a $10,000 loan from a wealthy Texas Alliance member and launched a new publication, The National Economist, in Washington, D.C.[1] He also started a publishing house at that same time, the Alliance Publishing Company.[1] These would become the official organ and official publishing house of the Southern Alliance, with Macune deeply involved in the affairs of each.

In 1890 Macune initiated a new concept called the Sub-Treasury Plan. This proposal called for the establishment of a network of government warehouses for the storage of non-perishable agricultural commodities (such as cotton), to be operated at minimal cost to participating farmers.[1] Farmers making use of the facilities could then draw low-interest loans of up to 80% of the value of their goods held in storage, payable in U.S. Treasury notes.[1] The Sub-Treasury idea became a main policy initiative of the Southern Farmers' Alliance after 1890 and was a primary cause of the group's move into partisan politics through a third party called the People's Party.[1]

A loyal Democrat, Macune grudgingly supported the People's Party (commonly known as the "Populists") through the fall of 1892, when he was embroiled in a scandal by allowing an associate to make use of the Farmers' Alliance mailing list for the distribution of Democratic campaign literature.[1] In the aftermath of this affair and amidst charges of financial improprieties with regards to the operation of The National Economist, Macune resigned his posts as editor and member of the National Executive Committee of the Southern Alliance.[1]

Later years

His participation in the Populist movement at an end, Charles Macune remained in Washington, D.C., as the editor of the Evening Star until 1895.[1] He then returned to Cameron, Texas, with his wife and six children and established a short-lived newspaper there.[1] Upon the failure of that publication, Macune gained a state license to practice law and in 1896 he opened a legal practice in Beaumont.[1] This was followed in 1900 by a move back to Central Texas and a return to the practice of medicine for a brief interval.[1]

Macune began to study for a position in the ministry of the Methodist church and in June 1901 he was licensed to preach.[1] Macune accepted his first Methodist pastorate at Copperas Cove, Texas, in 1902.[1] He spent the rest of his working life as a preacher in a series of small Southwestern towns, including a brief missionary stint in Mexico.[1]

Macune retired to Fort Worth, Texas, where he died on November 3, 1940, at the age of 89.[6]

Footnotes

- Bruce Palmer and Charles W. Macune, Jr., "Charles William Macune," Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- John D. Hicks, The Populist Revolt: A History of the Crusade for Farm Relief. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1931; pp. 106-07.

- Hicks, The Populist Revolt, pp. 108-109.

- Hicks, The Populist Revolt, pg. 109.

- Cecil Harper, Jr., "Farmers' Alliance Exchange of Texas," Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

- "Heard Lincoln and Douglas in Mighty Debate; Now Dies". The Waco News-Tribune. November 4, 1940. p. 3. Retrieved February 5, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading

- Donna A. Barnes, Farmers in Rebellion: The Rise and Fall of the Southern Farmers Alliance and People's Party in Texas. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1984.

- Lawrence Goodwyn, Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

- John D. Hicks, "The Sub-Treasury: A Forgotten Plan for the Relief of Agriculture," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 15, no. 3 (Dec. 1928), pp. 355–73.

- Robert C. McMath, Jr. Populist Vanguard: A History of the Southern Farmers' Alliance. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1975.

- Charles W. Macune, Jr., "The Wellsprings of a Populist: Dr. C. W. Macune Before 1886," Southwestern Historical Quarterly vol. 90 (October 1986).

- James C. Malin, "The Farmers' Alliance Subtreasury Plan and European Precedents," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. September 31, 1944.

- W. Scott Morgan, History of the Wheel and Alliance and the Impending Revolution. Fort Scott, KS: Rice, 1889.

- Piott, Steven L. American Reformers, 1870-1920: Progressives in Word and Deed (2006); examines 12 leading activists; see chapter 3 for Macune.

- Fred A. Shannon, C. W. Macune and the Farmers' Alliance," Current History, vol. 28 (June 1955).

- Ralph A. Smith, "'Macuneism,' or the Farmers of Texas in Business," Journal of Southern History, vol. 13 (May 1947).

External links

- Charles W. Macune Papers, Barker Texas History Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- Charles Macune at Find a Grave

- Charles William Macune (1851-1940). Biography with references at the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved August 27, 2006.