Charles Minot (railroad executive)

Charles Minot (August 30, 1810 - December 10, 1866) was an American railroad executive at the Erie Railroad, where in 1850 he became Superintendent as successor of James P. Kirkwood, and was succeeded by Daniel McCallum in 1854. After the bankruptcy of the Erie in 1859 he was reinstated as general superintendent of the Erie railroad.

Biography

Minot was born at Haverhill, Massachusetts. His father, Stephen Minot (1776–1861), was a judge of the Massachusetts Supreme Court. Charles Minot was educated for the law, and graduated at Harvard in 1828.[1] However, Minot's mind was of a more practical bent, and he learned to be an engineer on the Boston and Maine Railroad, of which railroad he subsequently became superintendent.

Minot was one of the first to learn telegraph, and his knowledge of that new science stood him well in his career as superintendent of the Erie, as we have seen in the account of his adapting the telegraph to the use of the railroad. He came to the Erie from the Boston and Maine Railroad. The Erie was then in operation as far west as Elmira. On May 1, 1850 he became General Superintendent as successor of James P. Kirkwood.[2]

Charles Minot was a large, fleshy man, very democratic in his manner with his men, always meeting them on an apparent equality. He was a bluff and rude man in his speech, and hasty of temper. A peculiarity of his character was that if he summoned any of the men to his office to "blow them up," he would deliver his pent-up feelings on the first person who happened to come in, although that one was in no way concerned in the trouble on hand, and perhaps knew nothing about it. Minot's mind relieved, all would be serene again, and when the man he had summoned came in, he would be dismissed without a word.[2]

Superintendent Minot was continually travelling over the road. He had no special car or retainers, such as general superintendents of to-day are sumptuously equipped with. "Any car is good enough for me," Minot used to say. He frequently travelled with the pay car, to save expense. Until one day in the summer of 1853, he invariably travelled with his car ahead of the engine. He acknowledged that this was a dangerous thing to do, but he said "he could see things better." On the day in question, the car jumped the rails near Almond on the Western Division, at a high embankment there. With him on the car was President Homer Ramsdell and H.G. Brooks. Minot was a powerful man. He was standing on the platform as the car left the track. President Rainsdell and Mr. Brooks rushed for the door to escape, but they never would have got out but for Minot, who seized the president with one hand and Brooks with the other, dragged them through the door, and jumped from the car with them just as it toppled over the bank. That was the last trip Minot ever took over the road with his car in front of the locomotive.[2]

The democratic manner of Superintendent Minot had made him objectionable to a number of the Directors long before he declined to enforce the McCallum rules, among them President Ramsdell, so although he had proved himself a capable railroad man, his withdrawal in favor of the strict disciplinarian, McCallum, was agreeable to that element in the Board in more ways than one - but it was costly to the Erie. Minot went from the Erie to the Michigan Southern Railroad, as general manager, a place he held until December 1859. Then he was recalled to the general superintendency of the Erie. He remained at the head of the operative department until December 31, 1864, when he was succeeded by Hugh Riddle. For a time Mr. Minot held an office with the Company known as consulting engineer, but he retired from that and returned to his native place, where he died.[2]

Work

Bringing the telegraph into use for railroading

.jpg.webp)

The Erie, through Charles Minot, and through his successor, D. C. McCallum, attracted the eyes of the whole country to the value of the telegraph as a vital agent in the management of railroads, the running of trains, and the safety of passengers. What was known as the New York and Erie Telegraph Line was begun in August, 1847. It was not a work of the New York and Erie Railroad Company.[3]

In 1847, Ezra Cornell of Ithaca, New York worked to expand telegraphic communication through the New York and Lake Erie Railroad right-of-way with the Western Union Telegraph Company,[4] saving a telegraph line he built from New York City to Fredonia.[5] The new telegraph was an instant hit, and was commonly used for gossip and casual chatting.[6]

Ezra Cornell was the projector of the line, and while he was constructing it through the southern New York counties, taking the wagon roads for his route, Charles Minot was watching him. Minot early saw the value of the telegraph to railroads, and how it might be employed to direct the movement of trains at every point along the road. He induced the Railroad Company to construct a line of telegraph poles and wires along the margin of the railroad, without reference to patents, and without determining the machinery to be employed. It was constructed by the railroad workmen. Mr. Cornell supplied insulators and also Morse machinery for the offices to be opened. The insulators were of brimstone, enclosed in iron pots, and of but small value.[3]

On the completion of the Erie telegraph line, Superintendent Minot offered to purchase for the Erie the Morse patent on fair terms. Mr. Smith, one of the owners of the patent, refused to sell. He invited the New York and Erie Railroad Company to become stockholders in the Telegraph Company, and thus acquire the right to use the Morse instruments. By this time, however, the Cornell line had so shown its unreliable character that Mr. Minot declined the invitation. He wrote, also, very placidly to Mr. Smith that his notion was that, after its completion, "our Company would make arrangements with the New York and Erie Telegraph Company to work it for us."

After a short struggle against circumstances the wire of the Cornell line was, in 1852 and 1853, transferred from the poles along the turnpikes to those of the Railroad Company, and by gradual processes the line became massed with and faded into the property of that Company. In 1852 the title of the company was changed to The New York and Western Union Telegraph.[3]

The telegraph system at Erie

The novelty and importance of applying the telegraph to the running of its trains by the Erie did not begin to attract general attention until 1855. In his report for that year, John T. Clark, in his function as New York State Engineer and Surveyor, referred to this innovation at length. As his statements describe accurately the system of operation on the Erie that had gradually developed under the telegraphic adjunct, and which, modified and improved by Superintendent Minot and his successor, Daniel McCallum, eventually became the standard system on railroads everywhere, they are reproduced here as interesting and valuable historic data:[7]

- The telegraph has been in use on the Erie since 1852 [meaning practically]. By the concurrent testimony of the superintendents of the road, it has saved more than it cost every year. There is an operator at every station on the line, and at the important ones day and night, so placed that they have a fair view of the track. They are required to note the exact time of the arrival, departure, or passage of every train, and to transmit the same by telegraph to the proper officer. On each division there is an officer called train despatcher, whose duty it is to keep constantly before him a memorandum of the position of every train upon his division, as ascertained by the telegraphic reports from the several stations. The trains are run upon this road by printed time-tables and regulations. When they become disarranged, the telegraph is also used to disentangle and move them forward. When trains upon any part of this road are delayed, the fact is immediately communicated to the nearest station, and from there by telegraph to every station on the road. Approaching trains are thus warned of the danger, and accidents from this cause are prevented.[8]

- When one or more of the trains from any general cause, like that of snow storms, etc., have been retarded and are likely to produce delays on the other trains, the train despatcher is authorized to move them forward by telegraph under certain rules which have been arranged for that purpose. Having before him a schedule of the time of the passage of each train at its last station, he can determine its position at any desired moment with sufficient accuracy for his present purpose, and can adopt the best means of extricating the delayed trains and of regulating the movement of all so as to avoid any danger of collision or further entanglement. He then telegraphs to such stations as are necessary, giving orders to some trains to lay by for a certain period, or until certain trains have passed, and to others to proceed to certain stations and there await further orders.[8]

- To prevent any error or misunderstanding between the despatcher and the conductor of the train, he is required to write his order in the telegraph operator's book. The operator who receives the message is required to write it upon his book, and to fill up two printed copies, one of which he hands to the conductor of the train, and one to the engineman. The despatcher then transmits a message to the conductor, asking him the question : " How do you understand my message?" To which the conductor must make reply in his own words, repeating the substance of the message as he understands it, to detect any error which may be made by the operator, or of his own understanding of it. If this is satisfactory to the despatcher, he telegraphs, " All right, go ahead ! " and until this final message is received, no trains can be moved on the road by telegraph. Time is saved by using abbreviations for stations and messages, trains, etc.[8]

- In this way, if a passenger train is delayed an hour or more, all freight trains which would be held by it at the several stations under the general rules are moved forward to such other passing places as they are certain to reach before the delayed trains could overtake them, and thus it frequently happens that in a single day the trains which would otherwise be delayed, are moved forward by telegraph, the equivalent to the use of two or three engines and trains.[8]

The blank orders that were the basis of telegraphic running of trains originated with Superintendent McCallum, in 1854. They became famous as " Blank 31," " Blank 32," and " Blank A." The use of Blank 31 came under Rule 12 of the McCallum code, which was that "when a meeting place is to be made for trains moving in contrary directions, the right to run shall be made certain, positive, and defined, without regard to time."[7]

Train dispatching

Charles Minot as Division Superintendent on the Erie Railroad is credited with the first effort to control the movement of a train beyond the rule book and operating timetable, when, in September 1851, he sent a telegram to a railroad employee at another location directing that all trains be held at that point until the train Minot was riding could arrive.

On September 22, 1851, Minot was in a parked passenger train at Turner Station. He glanced out the window of the train and saw the new telegraph wires. Departing the train, Minot ran into the station, got on the new telegraph, and wired the next station along the line, Monroe, to see if the eastbound train to Piermont-on-Hudson had gone past. The station agent said no. At that point, Minot ordered the engineer of the train to proceed on their way to Goshen.[9] The engineer refused to take Minot's order, and instead, Minot got into the cab car himself and drove the train himself to Port Jervis, hours ahead of the planned scheduled time of arrival.[10] This was the second of the several "firsts" the Erie Railroad created in its time, along with the shipment of milk by rail at Chester station in 1842.[11]

Minot further developed a system using telegraphs for train dispatches, for use when trains would want to pass one another along the line, such as at stations. Two-letter telegraph codes were designated, and the new modern system was set up. For the ten years of the new railroad's existence, passengers had been disgusted as trains waited for hours as another train had to pass them. This new system would relieve this issue.[9]

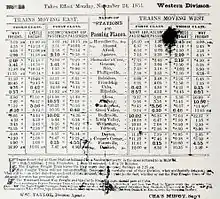

From that beginning, a system of train dispatching evolved. The operating rule book, later standardized for all railroads, contained the basic rules for the operation of trains, such as the meaning of the all fixed, audible and hand signals; the form, format and meaning of train orders; and the duties and obligations of each class of employee. The operating, or official, timetable established train numbers and schedules; meeting points for those trains; showed the length of passing tracks at each station as well as indicating the locations where train orders might be issued and contained a variety of other information which might be necessary or useful to train crews operating trains over the territory covered.

The use of the telegraph and Minot's system remained until 1888, when a new system of block signaling, developed by the competitor Pennsylvania Railroad, helped expand Minot's use of telecommunications to control rail traffic.[9]

Publications

- Samuel Marsh and Charles Minot "New York and Erie Railroad report" in: Report of the State Engineer and Surveyor on the Railroads of the State of New York. by New York (State). Board of Railroad Commissioners. 1862. p. 174-194

About Minot and his work

- Hungerford, Edward (1946). Men of Erie. Kingsport, Tennessee: Random House. OCLC 500324.

- Oslin, George P. (1999). The Story of Telecommunications. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-659-2.

- Yanosey, Robert J. (2006). Erie Railroad Facilities (In Color). Vol. 2: New York. Scotch Plains, New Jersey: Morning Sun Books Inc. ISBN 1-58248-196-2.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from

Edward Harold Mott Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie. Collins, 1899. p. 430-31; and other public domain material from books and websites.

This article incorporates public domain material from

Edward Harold Mott Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie. Collins, 1899. p. 430-31; and other public domain material from books and websites.

- William Thomas Davis (1895) Bench and Bar of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. p. 399

- Edward Harold Mott Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie. Collins, 1899. p. 430-31

- Edward Harold Mott (1899), p. 415

- Hungerford 1946, p. 92.

- Oslin 1999, p. 59.

- Hungerford 1946, pp. 92–93.

- Edward Harold Mott (1899), p. 421

- John T. Clark (1855) in his annual report as New York State Engineer. Cited in: Edward Harold Mott (1899), p. 421

- Hungerford 1946, p. 93.

- Hungerford 1946, pp. 93–94.

- Yanosey 2006, p. 19.

External links

- Charles Minot, National Railroad Hall

- A Monument to Charles Minot