Cosmic ocean

A cosmic ocean, primordial waters, or celestial river is a mythological motif that represents the world or cosmos enveloped by a vast primordial ocean. Found in many cultures and civilizations, the cosmic ocean exists before the creation of the earth. From the primordial waters the earth and the entire cosmos arose. The cosmic ocean represents or embodies chaos.

The cosmic ocean is present in the mythology of the Yazidis, Yarsanis, Alevi, Ancient Egyptians, Ancient Greeks, Jews, Ancient Indians, Ancient Persians, Sumerians, and Zoroastrians.

The primacy of the ocean in some creation myths corresponds to the cosmological model of land surrounded by the world ocean. The sky is often thought of as something like the upper sea. The concept of a watery chaos also underlies the widespread motif of the worldwide flood that took place in early times. The emergence of earth from water and the curbing of the global flood or underground waters are usually presented as a factor in cosmic ordering.

Background

In ancient creation texts, the primordial waters are often represented as having filled the entire universe and are the first source of the gods. The act of creation is the establishment of an inhabitable space separate from the enveloping waters.[1] The cosmic ocean is the shape of the universe before creation.[2]

The ocean is boundless, unordered, unorganized, amorphous, formless, dangerous, and terrible. In some myths, its cacophony is noted, opposed to the ordered rhythm of the sea.[3]

Chaos can be personified as water or by the unorganized interaction of water and fire. The transformation of chaos into order is also the transition from water to land.[4] In many ancient cosmogonic myths, the ocean and chaos are equivalent and inseparable from each other. The ocean remains outside space even after the emergence of the land. At the same time, the ability of the ocean to generate is realized in the appearance of the earth from it and in the presence of a mythological creature in the ocean that promotes generation or, on the contrary, zealously defends the "old order" and prevents the beginning of the chain of births from the ocean.[3]

Common themes

Yu. E. Berezkin and E. N. Duvakin generalize the motif of primary waters as follows: "Waters are primary. The earth is launched into the water, appears above the water, grows from a piece of solid substance placed on the surface of the water or liquid mud, from an island in the ocean, is exposed when the waters subsided, etc."[5]

The idea of the primacy of the ocean as an element, from the bowels of which the earth arises or is created, is universally prevalent.[1] This representation is present in many mythologies of the world.[6]

In Asia and North America, the earth-diver myth is found. In this myth a creator god dives into the cosmic ocean to bring up and form the earth.[7] A diving bird, catching a lump of earth from the primordial ocean, often appears in the mythologies of the Native Americans and Siberian peoples. In totemic myths, bird people are often presented as phratrial ancestors. Eggs are a common theme in creation myths. A waterfowl extracts silt from the sea, from which land is gradually created.[7]

In Polynesian mythology, Maui fishes islands out of the ocean. In Scandinavian mythology, the gods raise the earth, and Thor catches the "serpent of middle earth", which lives at the botom of the ocean. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the earth itself comes to the surface in the form of a mound. In the Brahmana it was said that Prajapati took the earth out of the water, taking the form of a boar.[4]

In the mythologies of many Asian countries, in which there is an image of an endless and eternal primordial ocean or sea, there is a motif of the creation of the earth by a celestial being descending from the sky and interfering with the water of the ocean with an iron club, spear or other object. This results in condensation which gives rise to the earth. In Japanese mythology, the islands of Japan arose from foam raised by mixing the waters of the ocean with the spear of the gods (Izanagi and Izanami). In the mythologies of the Mongolian peoples, the role of the compactor of the ocean waters is played by the wind, which creates a milky substance out of them, which then becomes the earth's firmament. According to the Kalmyks, plants, animals, people and gods were born from this milky liquid. Indian mythology has a similar myth about the churning of the Ocean of Milk

Myths about the world's oceans are universally accompanied by myths about its containment when the earth was already created, and myths about the attempts of the ocean to regain its undivided dominance. In Chinese mythology, there is the idea of a giant depression or pit that determines the direction of the ocean waters and takes away excess water. In many mythologies there are numerous narratives regarding the flood.

The opposition of two types of myths is known (for example, in Oceania) – about the earth sinking in the ocean, and about the retreat of the ocean or sea. An example of the first type is the legend about the origin of Easter Island, recorded on this island. In the creation myth of the Nganasan people, at first the earth was completely covered with water, then the water subsides and exposes the top of the Shaitan ridge Koika-mou. The first two people fall to this peak – a man and a woman. In the myth of creation of the Tuamotu Islands, the creator Tāne, "Spilling Water", created the world in the waters of the lord of the waters, Pune, and invoked the light that initiated the creation of the earth.[3]

The motif of the cosmogonic struggle with the serpent (dragon) is widespread in terms of suppressing water chaos. The serpent in most mythologies is associated with water, often as its abductor. He threatens either with a flood or a drought, that is, a violation of the measure, the water "balance". Since the cosmos is identified with order and measure, chaos is associated with the violation of measure. The Egyptian Ra-Atum fights the underground serpent Apep, the Indian Indra – with Vritra, who took the form of a snake, the Mesopotamian Enki, Ninurta or Inanna – with the owner of the underworld Kur, the Iranian Tishtry (Sirius) – with the deva Aposhi. Apop, Vritra, Kur and Aposhi hold back the cosmic waters. Enlil or Marduk defeats the progenitor Tiamat, the wife of Apsu, the personification of the dark waters of chaos, who has taken the form of a dragon. There are hints in the Bible about the struggle of God with a dragon or a wonderful fish, which also represents water chaos (Rahab, Tehom, Leviathan). Yu the Great's heroic struggle with the cosmic flood ends with the murder of the insidious owner of the water Gungun and his "close associate" – the nine-headed Xiangliu.

The transition from the formless water element to land is the most important act necessary for the transformation of chaos into space. The next step in the same direction is the separation of the sky from the earth, which, perhaps, essentially coincides with the first act, given the initial identification of the sky with the oceans. But it was precisely the repetition of the act – first down, and then up – that led to the allocation of three spheres – earthly, heavenly and underground, which represents the transition from binary division to trinity. The middle sphere, the earth, opposes the watery world below and the heavenly world above. A trichotomous scheme of the cosmos arises, including the necessary space between earth and sky. This space is often represented as a cosmic tree. Earth and sky are almost universally represented as feminine and masculine, a married couple standing at the beginning of a theogonic or theocosmogonic process. At the same time, the feminine principle is sometimes associated with the element of water and with chaos; usually it is conceived on the side of "nature" rather than "culture."

Mythical creatures personifying chaos, defeated, shackled, and overthrown, often continue to exist on the outskirts of space, along the shores of the oceans, in the underground "lower" world, in some special parts of the sky. So, in Scandinavian mythology, frost giants precede time, and in space they are located on the outskirts of the earth's circle, in cold places, near the oceans.[4]

In world cultures

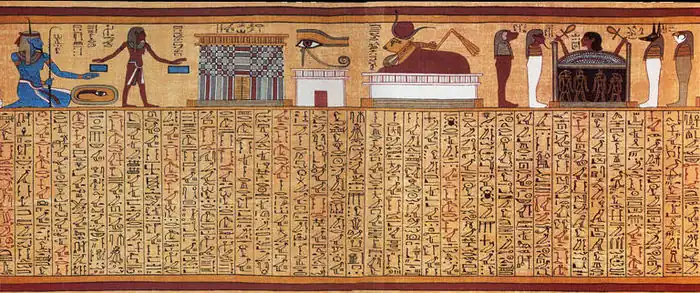

Egyptian mythology

In Ancient Egyptian mythology, in the beginning, the universe only consisted of a great, chaotic cosmic ocean, and the ocean itself was referred to as Nu. In some versions of this myth, at the beginning of time Mehet-Weret, portrayed as a cow with a sun disk between her horns, gives birth to the sun, said to have risen from the waters of creation and to have given birth to the sun god Ra in some myths.[8] The universe was enrapt by a vast mass of primordial waters, and the Benben, a pyramid mound, emerged amid this primal chaos. There was a lotus flower with Benben,[9] and this when it blossomed emerged Ra.[10] There were many versions of the sun's emergence, and it was said to have emerged directly from the mound or from a lotus flower that grew from the mound, in the form of a heron, falcon, scarab beetle, or human child.[11][12] In Heliopolis, the creation was attributed to Atum, a deity closely associated with Ra, who was said to have existed in the waters of Nu as an inert potential being.

The concept of chaos is etymologically associated with darkness (kek), but primarily, chaos in the form of the primary ocean (Nu) or, in the Germanic version, five divine pairs representing its different aspects. The primary hill is identified with the sun god Ra. Water chaos is opposed by the first earthly mound protruding from it, with which Atum is associated in Heliopolis (as Ra-Atum), and in Memphis, Ptah. Initially, the existing ocean is personified in the image of the "father of the gods" Nu. In the historical era, the ocean, which was placed underground, gave rise to the river Nile. In the Heracleopolis version of the myth, an internal connection between the ocean and chaos is noted.[3]

Greek

The ideas of ancient Greek mythology about the ocean demonstrate a typologically more advanced stage, when the image of Oceanus becomes the object of "pre-scientific" research and natural philosophy. Oceanus is presented first of all as the greatest world river (Hom. Il. XIV 245),[3] surrounding the earth and the sea,[13] giving rise to rivers, springs, sea currents (XXI 196), shelter of the sun, moon and stars, which they rise from the ocean and enter it (VII 422; VIII 485). The Ocean River touches the sea, but does not mix with it.[3] In the extreme west, the ocean washes the boundaries between the world of life and death.[14]

In Homer, Oceanus is without beginning. In Theogony 282, Hesiod Hesiod presents a folk etymology of the name Pegasus as derived from πηγή pēgē 'spring, well', referring to "the pegai of Okeanos, where he was born".[15] In Homer and Hesiod, the Ocean is a living being, the progenitor of all gods and titans (Hom. Il. XIV 201, 246), but Oceanus also had parents. According to Hesiod, Oceanus is the son of the oldest of the titans Uranus and Gaia (Theogony 133).[3] Oceanus is the brother and husband of Tethys, from whom he gave birth to all the rivers and sources[13] – three thousand daughters – oceanids (Theogony 346–364) and the same number of sons – river flows (Theogony 367–370).[14] The gods revere Oceanus as an aged parent, take care of him, although he lives in solitude.[3] Oceanus did not participate in the battle of the titans against Zeus and retained its power and the trust of the Olympians. Oceanus is the father of Metis, the wise wife of Zeus (Apollod. I 2, 1). Known for his peacefulness and kindness (Euripides tried unsuccessfully to reconcile Prometheus with Zeus; Prometheus Bound 284–396).[14] Herodotus contains criticism of the mythological concept of Oceanus as a poetic invention (Herodot. II, 23, cf. also IV 8, 36, etc.). Euripides called the ocean the sea (Orestes 1376). Since that time, a tendency has been established to distinguish between a large outer sea – ocean – and inland seas. Later, Euripides begins to divide the ocean into parts: the Ethiopian Ocean, Eritrean ocean, Gallic ocean, Germanic Ocean, Hyperborean Ocean, etc.[3]

Indian mythology

In Indian mythology, there is an idea of darkness and the abyss (Asat), but also of the primary waters generated by night or chaos.[4] Ancient Indian myths about the oceans contain both typical and original motifs. In the tenth mandala of the Rigveda, the original state of the universe is presented as the absence of existing and non-existent, airspace and sky above it, death and immortality, day and night, but the presence of water and disorderly movement. In the waters of the eternal ocean, there was a life-giving principle generated by the power of heat and giving birth to everything else. Another mandala of the Rigveda contains a different version: "Law and truths were born from the kindled heat...", hence the surging ocean. Out of the tumultuous ocean a year was born, distributing days and nights. "Rigveda" repeatedly mentions the generative power of the ocean ("multiple," it roars at its first spread, giving rise to creations, the bearer of wealth), its thousands of streams flowing from the depths, it is said that the ocean is the spouse of rivers. The cosmic ocean forms the frame of the cosmos, separating it from chaos. The ocean is personified by the god Varuna . Varuna is associated both with the destructive and uncontrolled power of the waters of the oceans, and with fruitful waters that bring wealth to people.[3]

The churning of the ocean of milk myth contains the motif of the confrontation between the elements of water and fire. As a result of the rapid rotation, a whorl lights up – Mount Mandara, but trees and grasses emit their juices into the drying ocean. This motif echoes the Tungus myths about the creation of the earth by a celestial being, which, with the help of fire, dries up part of the primordial ocean, thus reclaiming a place for the earth. The motif of the struggle of water and fire in connection with the theme of the world ocean is also present in other traditions.

Indian mythology is characterized by the image of the creator god (Brahma or Vishnu), floating on the primary waters in a lotus flower, on the Naga Shesha.[4]

Kurma, also known as Tortoise, is an avatar of Vishnu who is depicted as churning the cosmic ocean.[16] Vishnu adopts the form of a tortoise to help hold the stick used to churn the cosmic ocean.[16]

Persian mythology

Fraxkard (Middle Persian: plʾhwklt, Avestan: Vourukaša; also called Warkaš in Middle Persian) is the cosmic ocean in Iranian mythology.[17]

Judaism

In the first creation story in the Bible the world is created as a space inside of the water or Tehom, and is hence surrounded of it, "And God saith, 'Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.'" (Genesis 1:6). It is not clear as to if this upper water refers to the clouds or a literal 'sky ocean' beyond the stars. There are hints though that indicate the cosmic ocean was enveloped in thick clouds.

In Exodus the cosmic ocean is Yam Sûf and is mentioned in Exodus 15:4. The army of the Pharoh was thrown into the "Sea of Extinction." Yahweh rises Egypt up from this sea.[18] King Sargon is said to have washed his weapons in the cosmic ocean. The cosmic ocean is mentioned again in Joshua 1:4 and signified as a boundary of the universe.[18]

In the myth of Noah's Ark, after forty days and nights of rain the cosmic ocean floods the earth.[18]

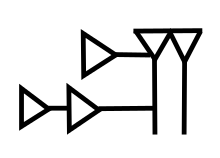

Sumerian mythology

In Sumerian mythology, there was an image of the original sea abyss – Abzu, on the site of which the most active of the gods Enki, representing the earth, fresh water and agriculture on irrigated lands, made his home.[4] In the beginning, the entire space of the world was filled with an ocean that had neither beginning nor end. It was probably believed that he was eternal. In its bowels lurked the foremother Nammu. In her womb arose a cosmic mountain in the form of a hemisphere, which later became the earth. An arc of shiny tin, encircling the hemisphere vertically, later became the sky. In the Babylonian version, in the endless primordial Ocean there was nothing but two monsters – the forefather Apsu and foremother Tiamat.[3]

Zoroastrianism

Vourukasha is the name of a heavenly sea in Zoroastrian mythology. It was created by Ahura Mazda and in its middle stood the Harvisptokhm or the "tree of all seeds".[19]

According to the Vendidad, Ahura Mazda sent the clean waters of Vourukasha down to the earth in order to cleanse the world and sent the water back to the heavenly sea Puitika. This phenomenon was later interpreted as the coming and going of the tide. At the centre of Vourukasha was located the Harvisptokhm or "tree of all seeds", which contains the seeds of all plants in the world. There is a bird Sinamru on the tree which causes the bough to break and seeds to sprinkle all around when it alights.[19]

At the center of the Vourukasha also grows the Gaokerena or "White Haoma", considered to be the "king of healing plants". [20] It is surrounded by ten thousand other healing plants.[19]

In later times, Vourukasha was connected with the Persian Sea and the Puitika with the Gulf of Oman.[19]

See also

References

- Buxton, Smith & Bolle 2022.

- Wyatt 2001.

- Toporov 2008, pp. 751–752.

- Meletinsky 2006.

- Beryozkin & Duvakin 2021.

- Greenwood 2015, p. 63.

- "Nature worship | Rituals, Animism, Religions, & History | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- The Complete Gods And Goddesses Of Ancient Egypt.

- "Ancient Egyptian Creation Myths: From Watery Chaos to Cosmic Egg". Glencairn Museum. July 13, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- "Lotus - Sunnataram Forest Monastery". www.sunnataram.org. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- Allen, Middle Egyptian, p. 144.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 206–207. ISBN 0-500-05120-8.

- Korsh 1894, p. .

- Takho-Godi 2008, p. 751.

- Noted by Karl Kerényi, The Heroes of the Greeks, 1959:80: "In the name Pegasos itself the connection with a spring, pege, is expressed."

- Laser 2014, p. 45.

- "Fraxkard". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Wyatt 2001, p. .

- Darmesteter 1880, p. 54.

- Darmesteter 1880, p. lxix.

Bibliography

- Beryozkin, Yury [in Russian]; Duvakin, Evgeny Nikolaevich (2021). "Тематическая классификация и распределение фольклорно-мифологических мотивов по ареалам" [Thematic classification and distribution of folklore and mythological motifs by areas]. B3A. Primary waters, A810 (in Russian).

- Laser, Tammy (2014). Gods & Goddesses of Ancient India. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 978-1-62275-391-8.

- Darmesteter, James (1880). The Sacred Books of the East. Oxford University Press.

Vol 4: The Zend Avesta, Part I: The Vendidad

- Greenwood, Kyle (2015). Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science. InterVarsity Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8308-9870-1.

- Korsh, M. (1894). A. S. Suvorina (ed.). Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей [Concise Dictionary of Mythology and Antiquities].

- Meletinsky, Yeleazar (2006). "ХАОС И КОСМОС. КОСМОГЕНЕЗ" [CHAOS AND COSMOS| COSMOGENESIS]. Poetics of myth (in Russian). Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Buxton, Richard G.A.; Smith, Jonathan Z.; Bolle, Kees W. (November 11, 2022). "myth". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "nature worship". Encyclopedia Britannica. April 15, 2023.

- Stiessel, Lena (1995). Skapelsemyter från hela världen (in Swedish). Almquist & Wiksell. ISBN 91-21-14467-2.

- Stoyanov, Yuri (February 2001). "Islamic and Christian heterodox water cosmogonies from the Ottoman period—paralleles and contrasts". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 64 (1): 19–33. doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000027. JSTOR 3657539. S2CID 162583636. INIST:1157309 ProQuest 214039469.

- Takho-Godi, Aza (2008). S. A. Tokarev. M. (ed.). Океан [Ocean]. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Toporov, Vladimir (2008). "Океан Мировой" [World Ocean]. Myths of the peoples of the world: Encyclopedia. (in Russian). pp. 751–752. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013.

- Wyatt, Nicolas (2001). Space and Time in the Religious Life of the Near East. A&C Black. pp. 55–133. ISBN 978-0-567-04942-1.