Cataphract

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalry that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

.jpg.webp)

The English word derives from the Greek κατάφρακτος kataphraktos (plural: κατάφρακτοι Kataphraktoi), literally meaning "armored" or "completely enclosed" (the prefix kata-/cata- implying "intense" or "completely"). Historically, the cataphract was a very heavily armored horseman, with both the rider and mount almost completely covered in scale armor, and typically wielding a kontos (lance) as his primary weapon.

Cataphracts served as the elite cavalry force for most empires and nations that fielded them, primarily used for charges to break through opposing heavy cavalry and infantry formations. Chronicled by many historians from the earliest days of antiquity up until the High Middle Ages, they may have influenced the later European knights, through contact with the Eastern Roman Empire.[1]

Peoples and states deploying cataphracts at some point in their history included: the Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, Parthians, Achaemenids, Sakas, Armenians, Seleucids, Attalid, Pontus, Greco-Bactrian, Sassanids, Romans, Goths, Byzantines, Georgians, Chinese, Koreans, Jurchens, Mongols, and Songhai.

In Europe, the fashion for heavily armored Roman cavalry seems to have been a response to the Eastern campaigns of the Parthians and Sasanians in Anatolia, as well as numerous defeats at the hands of Iranian cataphracts across the steppes of Eurasia, most notably in the Battle of Carrhae (53 BC) in upper Mesopotamia. Traditionally, Roman cavalry was neither heavily-armored nor decisive in effect; the Roman equites corps comprised mainly lightly-armored horsemen bearing spears and swords and using light cavalry tactics to skirmish before and during battles, and then to pursue retreating enemies after a victory. The adoption of cataphract-like cavalry formations took hold among the late Roman army during the late 3rd and 4th centuries. The Emperor Gallienus (r. 253–268 AD) and his general and putative usurper Aureolus (died 268) arguably contributed much to the institution of Roman cataphract contingents in the Late Roman army.

Etymology

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The origin of the word is Greek. Κατάφρακτος (kataphraktos, cataphraktos, cataphractos, or katafraktos) is composed of the Greek root words, κατά, a preposition, and φρακτός ("covered, protected"), which is interpreted along the lines of "fully armored" or "closed from all sides". The term first appears substantively in Latin, in the writings of Lucius Cornelius Sisenna: "loricatos, quos cataphractos vocant", meaning "the armored, whom they call cataphract".[3]

There appears to be some confusion about the term in the late Roman period, as armored cavalrymen of any sort that were traditionally referred to as Equites in the Republican period later became exclusively designated as "cataphracts". Vegetius, writing in the fourth century, described armor of any sort as "cataphracts" – which at the time of writing would have been either lorica segmentata or lorica hamata. Ammianus Marcellinus, Roman soldier and historian of the fourth century, mentions the "cataphracti equites (quos clibanarios dictitant)" – the "cataphract cavalry which they regularly call clibanarii" (implying that clibanarii is a foreign term, not used in Classical Latin).

Clibanarii is a Latin word for "mail-clad riders", itself a derivative of the Greek κλιβανοφόροι (klibanophoroi), meaning "camp oven bearers" from the Greek word κλίβανος, meaning "camp oven" or "metallic furnace"; the word has also been tentatively linked to the Persian word for a warrior, grivpan. However, it appears with more frequency in Latin sources than in Greek throughout antiquity. A twofold origin of the Greek term has been proposed: either that it was a humorous reference to the heavily armored cataphracts as men encased in armor who would heat up very quickly much like in an oven; or that it was further derived from the Old Persian word *griwbanar (or *grivpanvar), itself composed of the Iranian roots griva-pana-bara, which translates into "neck-guard wearer".[4]

Roman chroniclers and historians Arrian, Aelian and Asclepiodotus use the term "cataphract" in their military treatises to describe any type of cavalry with either partial or full horse and rider armor. The Byzantine historian Leo Diaconis calls them πανσιδήρους ἱππότας (pansidearoos ippotas), which would translate as "fully iron-clad knights".[5]

There is, therefore, some doubt as to what exactly cataphracts were in late antiquity, and whether or not they were distinct from clibanarii. Some historians theorise that cataphracts and clibanarii were one and the same type of cavalry, designated differently simply as a result of their divided geographical locations and local linguistic preferences. Cataphract-like cavalry under the command of the Western Roman Empire, where Latin was the official tongue, always bore the Latinized variant of the original Greek name, cataphractarii. The cataphract-like cavalry stationed in the Eastern Roman Empire had no exclusive term ascribed to them, with both the Latin variant and the Greek innovation clibanarii being used in historical sources, largely because of the Byzantines' heavy Greek influence (especially after the 7th century, when Latin ceased to be the official language). Contemporary sources, however, sometimes imply that clibanarii were in fact a heavier type of cavalryman, or formed special-purpose units (such as the late Equites Sagittarii Clibanarii, a Roman equivalent of horse archers, first mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum). Given that "cataphract" was used for more than a millennium by various cultures, it appears that different types of fully armored cavalry in the armies of different nations were assigned this name by Greek and Roman scholars not familiar with the native terms for such cavalry.

Iranian origins

.png.webp)

The reliance on cavalry as a means of warfare in general lies with the ancient inhabitants of the Central Asian steppes in early antiquity, who were one of the first peoples to domesticate the horse and pioneered the development of the chariot.[6] Most of these nomadic tribes and wandering pastoralists c. 2000 BC were largely Bronze-Age, Iranian populations who migrated from the steppes of Central Asia into the Iranian Plateau and Greater Iran from around 1000 BC to 800 BC. Two of these tribes are attested based upon archaeological evidence: the Mitanni and the Kassites. Although evidence is scant, they are believed to have raised and bred horses for specific purposes, as is evidenced by the large archaeological record of their use of the chariot and several treatises on the training of chariot horses.[7] The one founding prerequisite towards the development of cataphract cavalry in the Ancient Near East, apart from advanced metalworking techniques and the necessary grazing pastures for raising horses, was the development of selective breeding and animal husbandry. Cataphract cavalry needed immensely strong and endurant horses, and without selectively breeding horses for muscular strength and hardiness, they would have surely not been able to bear the immense loads of armor and a rider during the strain of battle.[8] The Near East is generally believed to have been the focal point for where this first occurred.

The previously mentioned early Indo-Iranian kingdoms and statehoods were to a large degree the ancestors of the north-eastern Iranian tribes and the Medians, who would found the first Iranian Empire in 625 BC. It was the Median Empire that left the first written proof of horse breeding around the 7th century BC, being the first to propagate a specific horse breed, known as the Nisean, which originated in the Zagros Mountains for use as heavy cavalry.[9] The Nisean would become renowned in the Ancient World and particularly in Ancient Persia as the mount of nobility. These warhorses, sometimes referred to as "Nisean chargers",[10] were highly sought after by the Greeks, and are believed to have influenced many modern horse breeds. With the growing aggressiveness of cavalry in warfare, protection of the rider and the horse became paramount. This was especially true of peoples who treated cavalry as the basic arm of their military, such as the Ancient Persians, including the Medes and the successive Persian dynasties. To a larger extent, the same can be said of all the Ancient Iranian peoples: second only to perhaps the bow, horses were held in reverence and importance in these societies as their preferred and mastered medium of warfare, due to an intrinsic link throughout history with the domestication and evolution of the horse.

These early riding traditions, which were strongly tied to the ruling caste of nobility (as only those of noble birth or caste could become cavalry warriors), now spread throughout the Eurasian steppes and Iranian plateau from around 600 BC and onwards due to contact with the Median Empire's vast expanse across Central Asia, which was the native homeland of the early, north-eastern Iranian ethnic groups such as the Massagetae, Scythians, Sakas, and Dahae.[9] The successive Persian Empires that followed the Medes after their downfall in 550 BC took these already long-standing military tactics and horse-breeding traditions and infused their centuries of experience and veterancy from conflicts against the Greek city-states, Babylonians, Assyrians, Scythians, and North Arabian tribes with the significant role cavalry played not only in warfare but everyday life to form a military reliant almost entirely upon armored horses for battle.

Spread to Central Asia and the Near East

The evolution of the heavily armored horseman was not isolated to one focal point during a specific era (such as the Iranian plateau), but rather developed simultaneously in different parts of Central Asia (especially among the peoples inhabiting the Silk Road) as well as within Greater Iran. Assyria and the Khwarezm region were also significant to the development of cataphract-like cavalry during the 1st millennium BC. Reliefs discovered in the ancient ruins of Nimrud (the ancient Assyrian city founded by king Shalmaneser I during the 13th century BC) are the earliest known depictions of riders wearing plated-mail shirts composed of metal scales, presumably deployed to provide the Assyrians with a tactical advantage over the unprotected mounted archers of their nomadic enemies, primarily the Aramaeans, Mushki, North Arabian tribes and the Babylonians. The Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) period, under which the Neo-Assyrian Empire was formed and reached its military peak, is believed to have been the first context within which the Assyrian kingdom formed crude regiments of cataphract-like cavalry. Even when armed only with pikes, these early horsemen were effective mounted cavalrymen, but when provided with bows under Sennacherib (705–681 BC), they eventually became capable both of long-range and hand-to-hand combat, mirroring the development of dual-purpose cataphract archers by the Parthian Empire during the 1st century BC.[11]

Archaeological excavations also indicate that, by the 6th century BC, similar experimentation had taken place among the Iranian peoples inhabiting the Khwarezm region and Aral Sea basin, such as the Massagetae, Dahae and Saka. While the offensive weapons of these prototype cataphracts were identical to those of the Assyrians, they differed in that not only the rider but also the head and flanks of the horse were protected by armor. Whether this development was influenced by the Assyrians, as Rubin postulates,[12] or perhaps the Achaemenid Empire, or whether they occurred spontaneously and entirely unrelated to the advances in heavily armored cavalry made in the Ancient Near East, cannot be discerned by the archaeological records left by these mounted nomads.[13]

The further evolution of these early forms of heavy cavalry in Western Eurasia is not entirely clear. Heavily armored riders on large horses appear in 4th century BC frescoes in the northern Black Sea region, notably at a time when the Scythians, who relied on light horse archers, were superseded by the Sarmatians.[14] By the 3rd century BC, light cavalry units were used in most eastern armies, but still only "relatively few states in the East or West attempted to imitate the Assyrian and Chorasmian experiments with mailed cavalry".[15]

Hellenistic and Roman adoption

The Greeks first encountered cataphracts during the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century BC with the Achaemenid Empire. The Ionian Revolt, an uprising against Persian rule in Asia Minor which preluded the First Persian invasion of Greece, is very likely the first Western encounter of cataphract cavalry, and to a degree heavy cavalry in general. The cataphract was widely adopted by the Seleucid Empire, the Hellenistic successors of Alexander the Great's kingdom who reigned over conquered Persia and Asia Minor after his death in 323 BC. The Parthians, who wrested control over their native Persia from the last Seleucid Kingdom in the East in 147 BC, were also noted for their reliance upon cataphracts as well as horse archers in battle.

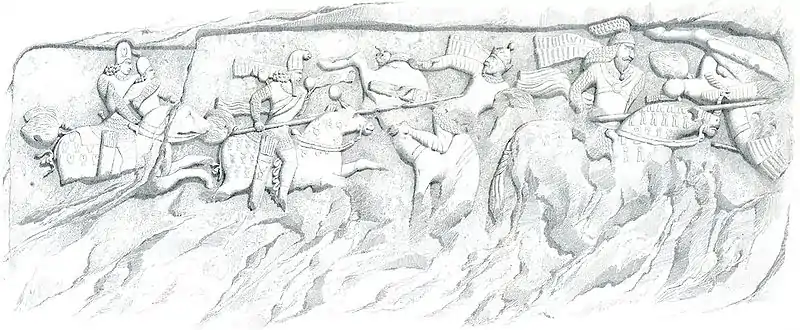

Besides the Seleucids it is possible that also the Kingdom of Pergamon adopted some cataphracts. Pergamese reliefs show cavalry similarly armed and equipped as Seleucid cataphracts, indicating an adoption. Yet these were probably equipped from trophies taken from the Seleucids,[16] which would suggest limited numbers.

The Romans came to know cataphracts during their frequent wars in the Hellenistic East. Cataphracts had varying levels of success against Roman military tactics more so at the Battle of Carrhae and less so at the battle of Lucullus with Tigranes the Great near Tigranocerta in 69 BC.[17][18] In 38 BC, the Roman general Publius Ventidius Bassus, by making extensive use of slingers, whose long-range weapons proved very effective, defeated the uphill-storming Parthian armored cavalry.[19]

At the time of Augustus, the Greek geographer Strabo considered cataphracts with horse armor to be typical of Armenian, Caucasian Albanian, and Persian armies, but, according to Plutarch, they were still held in rather low esteem in the Hellenistic world due to their poor tactical abilities against disciplined infantry as well as against more mobile, light cavalry.[18] However, the lingering period of exposure to cataphracts at the eastern frontier as well as the growing military pressure of the Sarmatian lancers on the Danube frontier led to a gradual integration of cataphracts into the Roman army.[20][21] Thus, although cavalrymen with armor were deployed in the Roman army as early as the 2nd century BC (Polybios, VI, 25, 3),[22] the first recorded deployment and use of cataphracts (equites cataphractarii) by the Roman Empire comes in the 2nd century AD, during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117–138 AD), who created the first, regular unit of auxiliary, mailed cavalry called the ala I Gallorum et Pannoniorum catafractata.[23] A key architect in the process was evidently the Roman emperor Gallienus, who created a highly mobile force in response to the multiple threats along the northern and eastern frontier.[24] However, as late as 272 AD, Aurelian's army, completely composed of light cavalry, defeated Zenobia at the Battle of Immae, proving the continuing importance of mobility on the battlefield.[25]

The Romans fought a prolonged and indecisive campaign in the East against the Parthians beginning in 53 BC, commencing with the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus (close benefactor of Julius Caesar) and his 35,000 legionaries at Carrhae. This initially unexpected and humiliating defeat for Rome was followed by numerous campaigns over the next two centuries entailing many notable engagements such as: the Battle of Cilician Gates, Mount Gindarus, Mark Antony's Parthian Campaign and finally culminating in the bloody Battle of Nisibis in 217 AD, which resulted in a slight Parthian victory, and Emperor Macrinus being forced to concede peace with Parthia.[17][18] As a result of this lingering period of exposure to cataphracts, by the 4th century, the Roman Empire had adopted a number of vexillations of mercenary cataphract cavalry (see the Notitia Dignitatum), such as the Sarmatian Auxiliaries.[20][21] The Romans deployed both native and mercenary units of cataphracts throughout the Empire, from Asia Minor all the way to Britain, where a contingent of 5,500 Sarmatians (including cataphracts, infantry, and non-combatants) were posted in the 2nd century by Emperor Marcus Aurelius (see End of Roman rule in Britain).[26]

This tradition was later paralleled by the rise of feudalism in Christian Europe in the Early Middle Ages and the establishment of the knighthood particularly during the Crusades, while the Eastern Romans continued to maintain a very active corps of cataphracts long after their Western counterparts fell in 476 AD.

Appearance and equipment

.jpg.webp)

But no sooner had the first light of day appeared, than the glittering coats of mail, girt with bands of steel, and the gleaming cuirasses, seen from afar, showed that the king's forces were at hand.

— Ammianus Marcellinus, late Roman historian and soldier, describing the sight of Persian cataphracts approaching Roman infantry in Asia Minor, circa fourth century.[27]

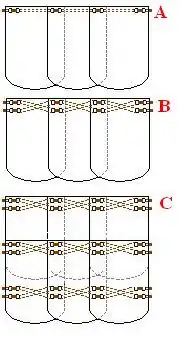

Cataphracts were almost universally clad in some form of scale armor (Greek: φολιδωτός Folidotos, equivalent to the Roman Lorica squamata) that was flexible enough to give the rider and horse a good degree of motion, but strong enough to resist the immense impact of a thunderous charge into infantry formations. Scale armor was made from overlapping, rounded plates of bronze or iron (most being around one to two millimeters thick), which had two or four holes drilled into the sides, to be threaded with a bronze wire that was then sewn onto an undergarment of leather or animal hide, worn by the horse. A full set of cataphract armor consisted of approximately 1,300 or so "scales" and could weigh an astonishing 40 kilograms or 88 pounds (not inclusive of the rider's body weight). Less commonly, plated mail or lamellar armor (which is similar in appearance but divergent in design, as it has no backing) was substituted for scale armor, while for the most part the rider wore chain mail. Specifically, the horse armor was usually sectional (not joined together as a cohesive "suit"), with large plates of scales tied together around the animal's waist, flank, shoulders, neck and head (especially along the breastplate of the saddle) independently to give a further degree of movement for the horse and to allow the armor to be affixed to the horse reasonably tightly so that it should not loosen too much during movement. Usually but not always, a close-fitting helmet that covered the head and neck was worn by the rider; the Persian variants extended this even further and encased the wearer's entire head in metal, leaving only minute slits for the nose and eyes as openings. Ammianus Marcellinus, a noted Roman historian and general who served in the army of Constantius II in Gaul and Persia and fought against the Sassanid army under Julian the Apostate, described the sight of a contingent of massed Persian cataphracts in the 4th century:

...all the companies were clad in iron, and all parts of their bodies were covered with thick plates, so fitted that the stiff-joints conformed with those of their limbs; and the forms of human faces were so skillfully fitted to their heads, that since their entire body was covered with metal, arrows that fell upon them could lodge only where they could see a little through tiny openings opposite the pupil of the eye, or where through the tip of their nose they were able to get a little breath. Of these some, who were armed with pikes, stood so motionless that you would think them held fast by clamps of bronze.[28]

The primary weapon of practically all cataphract forces throughout history was the lance. Cataphract lances (known in Greek as a Kontos ("oar") or in Latin as a Contus) appeared much like the Hellenistic armies' sarissae used by the famed Greek phalanxes as an anti-cavalry weapon. They were roughly four meters in length, with a capped point made of iron, bronze, or even animal bone and usually wielded with both hands. Most had a chain attached to the horse's neck and at the end by a fastening attached to the horse's hind leg, which supported the use of the lance by transferring the full momentum of a horse's gallop to the thrust of the charge. Though they lacked stirrups, the traditional Roman saddle had four horns with which to secure the rider;[29] enabling a soldier to stay seated upon the full impact. During the Sassanid era, the Persian military developed ever more secure saddles to "fasten" the rider to the horse's body, much like the later knightly saddles of Medieval Europe. These saddles had a cantle at the back of the saddle and two guard clamps that curved across the top of the rider's thighs and fastened to the saddle, thereby enabling the rider to stay properly seated, especially during violent contact in battle.[30]

The penetrating power of the cataphract's lance was recognized as being fearful by Roman writers, described as being capable of transfixing two men at once, as well as inflicting deep and mortal wounds even on opposing cavalries' mounts, and were definitely more potent than the regular one-handed spear used by most other cavalries of the period. Accounts of later period Middle Eastern cavalrymen wielding them told of occasions when it was capable of bursting through two layers of chain mail.[31] There are also reliefs in Iran at Firuzabad showing Persian kings doing battle in a fashion not dissimilar to later depictions of jousts and mounted combat from the Medieval era.[32]

Cataphracts would often be equipped with an additional side-arm such as a sword or mace, for use in the melee that often followed a charge. Some wore armor that was primarily frontal: providing protection for a charge and against missiles yet offering relief from the weight and encumbrance of a full suit. In yet another variation, cataphracts in some field armies were not equipped with shields at all, particularly if they had heavy body armor, as having both hands occupied with a shield and lance left no room to effectively steer the horse. Eastern and Persian cataphracts, particularly those of the Sassanid Empire, carried bows as well as blunt-force weapons, to soften up enemy formations before an eventual attack, reflecting upon the longstanding Persian tradition of horse archery and its use in battle by successive Persian Empires.

Tactics and deployment

While they varied in design and appearance, cataphracts were universally the heavy assault force of most nations that deployed them, acting as "shock troops" to deliver the bulk of an offensive manoeuvre, while being supported by various forms of infantry and archers (both mounted and unmounted). While their roles in military history often seem to overlap with lancers or generic heavy cavalry, they should not be considered analogous to these forms of cavalry, and instead represent the separate evolution of a very distinct class of heavy cavalry in the Near East that had certain connotations of prestige, nobility, and esprit de corps attached to them. In many armies, this reflected upon social stratification or a caste system, as only the wealthiest men of noble birth could afford the panoply of the cataphract, not to mention the costs of supporting several war horses and ample amounts of weaponry and armor.

Fire support was deemed particularly important for the proper deployment of cataphracts. The Parthian army that defeated the Romans at Carrhae in 53 BC operated primarily as a combined arms team of cataphracts and horse archers against the Roman heavy infantry. The Parthian horse archers encircled the Roman formation and bombarded it with arrows from all sides, forcing the legionaries to form the Testudo or "tortoise" formation to shield themselves from the huge numbers of incoming arrows. This made them fatally susceptible to a massed cataphract charge, since the testudo made the legionaries immobile and incapable of attacking or defending themselves in close combat against the long reach of the Parthian cataphracts' Kontos, a type of lance. The end result was a far smaller force of Parthian cataphracts and horse archers wiping out a Roman army four times their number, due to a combination of fire and movement, which pinned the enemy down, wore them out and left them vulnerable to a deathblow.

The cataphract charge was very effective due to the disciplined riders and the large numbers of horses deployed. As early as the 1st century BC, especially during the expansionist campaigns of the Parthian and Sassanid dynasties, Eastern Iranian cataphracts employed by the Scythians, Sarmatians, Parthians, and Sassanids presented a grievous problem for the traditionally less mobile, infantry-dependent Roman Empire. Roman writers throughout imperial history made much of the terror of facing cataphracts, let alone receiving their charge. Parthian armies repeatedly clashed with the Roman legions in a series of wars, featuring the heavy usage of cataphracts. Although initially successful, the Romans soon developed ways to crush the charges of heavy horsemen, through use of terrain and maintained discipline.

Persian cataphracts were a contiguous division known as the Savaran (Persian: سواران, literally meaning "riders") during the era of the Sassanid army and remained a formidable force from the 3rd to 7th centuries until the collapse of the Sassanid Empire.[1] Initially the Sassanid dynasty continued the cavalry traditions of the Parthians, fielding units of super-heavy cavalry. This gradually fell out of favour, and a "universal" cavalryman was developed during the later 3rd century, able to fight as a mounted archer as well as a cataphract. This was perhaps in response to the harassing, nomadic combat style used by the Sassanids' northern neighbours who frequently raided their borders, such as the Huns, Hephthalites, Xiongnu, Scythians, and Kushans, all of which favoured hit and run tactics and relied almost solely upon horse archers for combat. However, as the Roman-Persian wars intensified to the West, sweeping military reforms were again re-established. During the 4th century, Shapur II of Persia attempted to reinstate the super-heavy cataphracts of previous Persian dynasties to counter the formation of the new, Roman Comitatenses, the dedicated, front-line legionaries who were the heavy infantry of the late Roman Empire. The elite of the Persian cataphracts, known as the Pushtigban Body Guards, were sourced from the very best of the Savaran divisions and were akin in their deployment and military role to their Roman counterparts, the Praetorian Guard, used exclusively by Roman emperors. Ammianus Marcellinus remarked in his memoirs that members of the Pushtigban were able to impale two Roman soldiers on their spears at once with a single furious charge. Persian cataphract archery also seems to have been again revived in late antiquity, perhaps as a response (or even a stimulus) to an emerging trend of the late Roman army towards mobility and versatility in their means of warfare.

In an ironic twist, the elite of the East Roman army by the 6th century had become the cataphract, modelled after the very force that had fought them in the east for more than 500 years earlier. During the Iberian and Lazic wars initiated in the Caucasus by Justinian I, it was noted by Procopius that Persian cataphract archers were adept at firing their arrows in very quick succession and saturating enemy positions but with little hitting power, resulting in mostly non-incapacitating limb wounds for the enemy. The Roman cataphracts, on the other hand, released their shots with far more power, able to launch arrows with lethal kinetic energy behind them, albeit at a slower pace.

Later history and usage in the early Middle Ages

.jpg.webp)

Some cataphracts fielded by the later Roman Empire were also equipped with heavy, lead-weight darts called Martiobarbuli, akin to the plumbata used by late Roman infantry. These were to be hurled at the enemy lines during or just before a charge, to disorder the defensive formation immediately before the impact of the lances. With or without darts, a cataphract charge would usually be supported by some kind of missile troops (mounted or unmounted) placed on either flank of the enemy formation. Some armies formalised this tactic by deploying separate types of cataphract, the conventional, very heavily armored, bowless lancer for the primary charge and a dual purpose, lance-and-bow cataphract for supporting units.

References to Eastern Roman cataphracts seemed to have disappeared in the late 6th century, as the manual of war known as Strategikon of Maurice, published during the same period, made no mention of cataphracts or their tactical employment. This absence persisted through most of the Thematic period, until the cataphracts reappeared in Emperor Leo VI's Sylloge Taktikon, probably reflecting a revival that paralleled the transformation of the Eastern Roman army from a largely defensive force into a largely offensive force. The cataphracts deployed by the Eastern Roman Empire (most noticeably after the 7th century, when Late Latin ceased to be the official language of the empire) were exclusively referred to as Kataphraktoi, due to the Empire's strong Greek influence, as opposed to the Romanized term Cataphractarii, which subsequently fell out of use.

These later Roman cataphracts were a much feared force in their heyday. The army of Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas reconstituted Kataphraktoi during the tenth century and included a complex and highly developed composition of an offensive, blunt-nosed wedge formation. Made up of roughly five hundred cavalrymen, this unit was clearly designed with a single decisive charge in mind as the centre of the unit was composed of mounted archers. These would release volleys of arrows into the enemy as the unit advanced at a trot, with the first four rows of mace-armed Kataphraktoi then penetrating the enemy formation through the resulting disruption (contrary to popular representations, Byzantine Kataphraktoi did not charge, they advanced at a steady medium-pace trot and were designed to roll over an enemy already softened by the archers). It is important to note that this formation is the only method prescribed for Kataphraktoi in the Praecepta Militaria of Emperor Nikephoros which was designed as a decisive hammer-blow which would break the enemy. Due to the rigidity of the formation, it was not possible for it to re-form and execute a second charge in instances where the first blow did not smash the enemy (no feigned flight or repeated charges were possible due to the formation employed). It is for this reason that Byzantine military manuals (Praecepta Militaria and the Taktika) advise where possible, for the use of a second wedge of Kataphraktoi which could be hurled at the enemy in the event that they resisted the initial charge.

Contemporary depictions, however, imply that Byzantine cataphracts were not as completely armored as the earlier Roman and Sassanid incarnation. The horse armor was noticeably lighter than earlier examples, being made of leather scales or quilted cloth rather than metal at all. Byzantine cataphracts of the 10th century were drawn from the ranks of the middle-class landowners through the theme system, providing the Byzantine Empire with a motivated and professional force that could support its own wartime expenditures. The previously mentioned term Clibanarii (possibly representing a distinct class of cavalry from the cataphract) was brought to the fore in the 10th and 11th centuries of the Byzantine Empire, known in Byzantine Greek as Klibanophoros, which appeared to be a throwback to the super-heavy cavalry of earlier antiquity. These cataphracts specialised in forming a wedge formation and penetrating enemy formations to create gaps, enabling lighter troops to make a breakthrough. Alternatively, they were used to target the head of the enemy force, typically a foreign emperor.

As with the original cataphracts, the Leonian/Nikephorian units seemed to have fallen out of favour and use with their handlers, making their last, recorded appearance in battle in 970 and the last record of their existence in 1001, referred to as being posted to garrison duty. If they had indeed disappeared, then it is possible that they were revived once again during the Komnenian restoration, a period of thorough financial, territorial and military reform that changed the Byzantine army of previous ages, which is referred to separately as the Komnenian army after the 12th century.[33] Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) established a new military force from the ground up, which was directly responsible for transforming the aging Byzantine Empire from one of the weakest periods in its existence into a major economic and military power, akin to its existence during the golden age of Justinian I. However, even in this case, it seems that the cataphract was eventually superseded by other types of heavy cavalry.

It is difficult to determine when exactly the cataphract saw his final day. After all, cataphracts and knights fulfilled a roughly similar role on the medieval battlefield, and the armored knight survived well into the early modern era of Europe. The Byzantine army maintained units of heavily armored cavalrymen up until its final years, mostly in the form of Western European Latinikon mercenaries, while neighbouring Bulgars, Serbs, Avars, Alans, Lithuanians, Khazars, and other Eurasian peoples emulated Byzantine military equipment. During medieval times, the Draco banner and Tamga of Sarmatian cataphracts belonging to the tribe of Royal Sarmatians, was used by the Clan of Ostoja and become Ostoja coat of arms.[34][35][36]

As Western European metalwork became increasingly sophisticated, the traditional image of the cataphract's awe-inspiring might and presence quickly evaporated. From the 15th century and onwards, chain mail, lamellar armor, and scale armor seemed to fall out of favour with Eastern noble cavalrymen as elaborate and robust plate cuirasses arrived from the West; this, in combination with the advent of early firearms, cannon, and gunpowder, rendered the relatively thin and flexible armor of cataphracts obsolete. Despite these advances, the Byzantine army, often unable to afford newer equipment en masse, was left ill-equipped and forced to rely on its increasingly archaic military technology. The cataphract finally passed into the pages of history with the Fall of Constantinople on 29 May 1453, when the last nation to refer to its cavalrymen as cataphracts fell (see Decline of the Byzantine Empire).

Cataphracts in East Asia

Horses covered with scale armor are alluded to in the ancient Chinese book of poetry, the Shi Jing dating between the 7th to 10th centuries BC—however, this armor did not cover the entire horse and was likely made of hide, not metal as traditionally believed (e.g. by Zhu Xi, Séraphin Couvreur, James Legge, etc.).[37][38][39][40][41] According to surviving records, the Western Han Dynasty had 5,330 sets of horse armor at the Donghai Armory. Comprehensive full-body armor for horses made of organic materials such as rawhide may have existed as early as the Qin Dynasty according to archaeological discoveries of stone lamellar armor for horses. Comprehensive armor for horses made of metal might have been used in China as early as the Three Kingdoms period, but the usage wasn't widely adapted as most cavalry formation requires maneuverability. It was not until the early 4th century, however, that cataphracts came into widespread use among with the Xianbei tribes of Inner Mongolia and Liaoning, which led to the readoption of cataphracts en masse by Chinese armies during the Jin dynasty (266–420) and Northern and Southern Dynasties era. Numerous burial seals, military figurines, murals, and official reliefs from this period testify to the great importance of armored cavalry in warfare. The later Sui Empire continued the use of cataphracts. During the Tang Empire it was illegal for private citizens to possess horse armor.[42] Production of horse armor was controlled by the government.[43] However, the use of cataphracts was mentioned in many records and literature.[44][45][46][47] Cataphracts were also used in warfare from the Anlushan Rebellion to the fall of the Tang Dynasty. During the Five Dynasties and 10 Kingdoms era, cataphracts were important units in this civil war.[48] In the same period, cataphracts were also popular among nomadic empires, such as the Liao, Western Xia, and Jin dynasties—the heavy cataphracts of the Xia and Jin were especially effective and were known as "Iron Sparrowhawks" and "Iron Pagodas" respectively. The Song Empire also developed cataphract units to counter those of the Liao, Xia, and Jin, but the shortage of suitable grazing lands and horse pastures in Song territory made the effective breeding and maintenance of Song cavalry far more difficult. This added to the Song's vulnerability to continual raids by the emerging Mongol Empire for over two decades, which eventually vanquished them in 1279 at the hands of Kublai Khan. The Yuan dynasty, successors to the Song, were a continuation of the Mongol Empire, and seem to have all but forgotten the cataphract traditions of their predecessors. The last remaining traces of cataphracts in East Asia seems to have faded with the downfall of the Yuan in 1368 and later heavy cavalry never reached the levels of armor and protection for the horses as these earlier cataphracts.

Other East Asian cultures were also known to have used cataphracts during a similar time period to the Chinese. Meanwhile, the Tibetan Empire used cataphracts as the elite assault force of its armies for much of its history.[49] The Gokturk Khaganates might also have had cataphracts, as the Orkhon inscriptions mentioned Latter Göktürk general Kul-Tegin exchanged armored horses in battle.[50]

References

- Nell, Grant S. (1995) The Savaran: The Original Knights. University of Oklahoma Press.

- KHALCHAYAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica. p. Figure 1.

- Nikonorov, Valerii P. (2–5 September 1998). Cataphracti, Catafractarii and Clibanarii: Another Look at the old problem of their Identifications. Военная археология: оружие и военное дело в исторической и социальной перспективе. Материалы Международной конференции [Military Archeology: Weapons and Military Affairs from a Historical and Social Perspective. Proceedings of the International Conference]. St. Petersburg. pp. 131–138.

- Nicolle, David (1992) Romano-Byzantine Armies, 4th–9th Centuries. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-8553-2224-2, 978-1-8553-2224-0

- Leo Diaconis, Historiae 4.3, 5.2, 8.9

- Mielczarek, Mariusz (1993) Cataphracti and Clibanarii. Studies on the Heavy Armoured Cavalry of the Ancient World, p. 14

- Robert Drews, "The Coming of the Greeks: Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and the Near East.", Princeton University Press, Chariot Warfare. p. 61.

- Perevalov, S. M. (translated by M. E. Sharpe) (Spring 2002). "The Sarmatian Lance and the Sarmatian Horse-Riding Posture". Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia 41 (4): 7–21.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2005). Sassanian Elite Cavalry, AD 224–642. Osprey Publishing.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2005). Sassanian elite cavalry AD 224–642. Oxford: Osprey. p. 4. ISBN 9781841767130. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- Eadie 1967, pp. 161f.

- Rubin 1955, p. 266

- Eadie 1967, p. 162

- Rubin 1955, pp. 269–270

- Eadie 1967, p. 163

- Head, Duncan (2016). Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars 359 BC to 146 BC. Lulu.com. p. 237. ISBN 9781326256562.

- Eadie 1967, pp. 163f.

- Perevalov 2002, p. 10

- Campbell 1987, p. 25

- Perevalov 2002, pp. 10ff.

- Eadie 1967, p. 166

- Rubin 1955, p. 276, fn. 2

- Eadie, John W. (1967). "The Development of Roman Mailed Cavalry". The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 57, No. 1/2 (1967), pp. 161–173.

- Eadie 1967, p. 168

- Eadie 1967, pp. 170f.

- D'Amato, Raffaele; Negin, Andrey Evgenevich (20 November 2018). Roman Heavy Cavalry (1): Cataphractarii & Clibanarii, 1st Century BC–5th. Elite. Vol. 225. Osprey Publishing. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-4728-3004-3.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, (353 AD) Roman Antiquities, Book XXV pp. 477

- Ammianus Marcellinus, (353 AD) Roman Antiquities, Boox XXV pp. 481

- Driel-Murray, C. van; Connolly, P. (1991). The Roman cavalry saddle. Britannia 22, pp. 33–50.

- Shahbazi, A. Sh. (2009). Sassanian Army.

- Usamah Ibn-Munquidh, An Arab-Syrian Gentleman and Warrior in the Period of the Crusades: Memoirs of Usamah Ibn-Munquidh, Philip K. Hitti (trans.) (New Jersey: Princeton), 1978. p. 69.

- "Equestrian battle reliefs from Firuozabad" Archived 2016-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Battle scenes showing combat between Parthian and Sassanian cataphracts on horses with barding using lances.

- J. Birkenmeier in "The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081-1180"

- "The Sarmatians 600 BC - AD 450", Brzezinski & Mielczarek, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1 84176 485 X

- "The Sarmatians", T. Sulimirski, ISBN 9780500020715

- Helmut Nickel, Tamga and Runes, Magic Numbers and Magic Symbols, The Metropolitan Art Museum 1973

- Berthold Laufer (1913), Notes on Turquois in the East, Volume 13, Issues 1–2, p. 306-307

- Classic of Poetry "Airs of Qin: Little War-Chariot" quote: "俴駟孔羣" translation: "The thinly-armoured horse-quartet are very harmonious".

- Zhu Xi Collected Commentaries on the Classic of Poetry, "volume 3" p. 68 of 163. quote: "俴駟,四馬皆以淺薄之金為甲。欲其輕而易於馬之旋習也。" translation: "thinly armoured horse-quartet: all four horses are armoured by thin metal plates. Horses need to be light as well as easily steered and trained."

- Classic of Poetry "Airs of Zheng: Men of Qing" quote: "駟介旁旁... 駟介麃麃... 駟介陶陶..." translation: "The armoured horse-quartet strutted strong... The armoured horse-quartet pranced proud... The armoured horse-quartet jaunted with joy..."

- Zhu Xi Collected Commentaries on the Classic of Poetry, "volume 4" p. 8 of 163. quote: "駟介,四馬而被甲也。" translation: "armoured horse-quartet, four forses covered by armours."

- Tang Code(唐律疏議). Vol.16 擅興, Code 243 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Tang Liu Dian (唐六典). Vol.22. 右尚署.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Liu 劉, Xu 昫 (945). Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.2 Emperor Taizong 太宗上. Official state history recorded Li Shimin (Emperor Taizong of Tang) commanding his Black Armor Cavalry Force to break and penetrate Dou Jiande's formation in Battle of Hulao (621 AD). On the ceremony of this triumph, the later emperor led a force of 10000 cataphracts and 30000 armored infantry.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Quan Tang Wen (全唐文) Vol. 352 河西破蕃賊露布. This military report recorded a border battle between Tang and Tibetan Armies in the middle 8th Century. Among the 5000 Tang cavalry troops, 1200 were cataphracts.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Quan Tang Wen (全唐文) Vol. 827 責南詔蠻書. In this official call to arms, the Tang military leader threatened the Nanzhao leaders by stating that he had 4 units of cataphracts, 500 in each unit.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Wang 王, Qinruo 欽若 (1013). Cefu Yuangui 冊府元龜 Vol.1 帝王部·修武備. The book recorded that the Tang arsenal once distributed 150 Modao glaives and 100 catapharact horse armors to border troops in Yanzhou in 8th century.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Li 李, Cunxu 存勖. Quan Tang Wen (全唐文) Vol.103 曉諭梁將王檀書. In this call for surrender, Li Cunxu (Emperor Zhuang of the later Tang) boasted that his soldiers captured 5000 cataphracts of the Later Liang Dynasty victory in the Battle of Baixiang (910 AD).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Du 杜, You 佑 (801). Tongdian 通典 Vol.4 Border defense·Tibet 邊防典·吐蕃.

- "The Kültegin inscription" lines 33-34 at Türk Bitig

Sources

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1972), "Cavalry Equipment and Tactics on the Euphrates Frontier", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 26: 271–291, doi:10.2307/1291323, JSTOR 1291323

- Campbell, Brian (1987), "Teach Yourself How to Be a General", Journal of Roman Studies, 77: 13–29, doi:10.2307/300572, JSTOR 300572, S2CID 162374857

- Eadie, John W. (1967), "The Development of Roman Mailed Cavalry", Journal of Roman Studies, 57 (1/2): 161–173, doi:10.2307/299352, JSTOR 299352, S2CID 163396768

- Nikonorov, Valerii P. (1985a). "The Parthian Cataphracts". Chetvertaia vsesoiuznaia shkola molodykh vostokovedov. T. I. Moscow. pp. 65–67.

- Smith, William; et al. (1890). "Cataphracti". A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (3rd ed.). The text of this book is now in the public domain.

- Nikonorov, Valerii P. (1985b). "The Development of Horse Defensive Equipment in the Antique Epoch". In Kruglikova, I. T. (ed.). Zheleznyi vek Kavkaza, Srednei Azii i Sibiri. Moscow: Nauka. pp. 30–35.

- Nikonorov, Valerii P. (1998). "Cataphracti, Catafractarii and Clibanarii: Another Look at the old problem of their Identifications". Voennaia arkheologiia: Oruzhie i voennoe delo v istoricheskoi i sotsial.noi perspektive (Military Archaeology: Weaponry and Warfare in the Historical and Social Perspective). St. Petersburg. pp. 131–138.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Perevalov, S. M. (2002), "The Sarmatian Lance and the Sarmatian Horse-Riding Posture", Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia, 41 (4): 7–21, doi:10.2753/aae1061-195940047, S2CID 161826066

- Rubin, Berthold (1955), "Die Entstehung der Kataphraktenreiterei im Lichte der chorezmischen Ausgrabungen", Historia, 4: 264–283

- Soria Molina, D. (2011) "Contarii, cataphracti y clibanarii. La caballería pesada del ejército romano, de Vespasiano a Severo Alejandro", Aquila Legionis, 14, pp. 69–122.

- Soria Molina, D. (2012) "Cataphracti y clibanarii. La caballería pesada del ejército romano, de Severo Alejandro a Justiniano", Aquila Legionis, 15, pp. 117–163.

- Soria Molina, D. (2013) "Cataphracti y clibanarii (y III). La caballería pesada del ejército romano-bizantino, de Justiniano a Alejo Comneno", Aquila Legionis, 16, 75-123.

- Warry, John Gibson (1980). Warfare in the Classical World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons, Warriors, and Warfare in the Ancient Civilisations of Greece and Rome. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Macdowall, Simon (1995). Late Roman Cavalryman, 236–565 AD. Osprey Publishing.

- Mielczarek, M. (1993) Cataphracti and Clibanari. Studies on the Heavy Armoured Cavalry of the Ancient World. Lodz: Oficyna Naukowa MS.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2005). Sassanian Elite Cavalry, AD 224–642. Osprey Publishing.

- Nell, Grant S. (1995). The Savaran: The Original Knights. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Marcellinus, Ammianus. Roman Antiquities, Book XXV. p. 481.

- José J. Vicente Sánchez (1999). Los regimientos de catafractos y clibanarios en la tardo antigüedad.

Antigüedad y cristianismo: Monografías históricas sobre la Antigüedad tardía, Nº 16, pages 397-418.ISSN 0214-7165.

External links

- Cataphracts and Siegecraft—Roman, Parthian and Sasanid military organisation.

- Image of Sarmatian armored horse detail on the Trajan's column project at McMaster University

- Third century AD graffito of Parthian Cataphractus

- The historical works of Ammianus Marcellinus