Carthage tophet

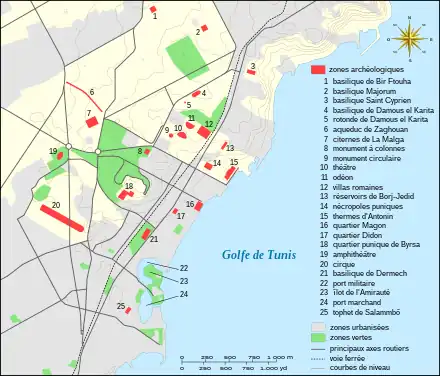

The Carthage tophet, is an ancient sacred area dedicated to the Phoenician deities Tanit and Baal, located in the Carthaginian district of Salammbô, Tunisia, near the Punic ports. This tophet, a "hybrid of sanctuary and necropolis",[1] contains a large number of children's tombs which, according to some interpretations, were sacrificed or buried here after their untimely death. The area is part of the Carthage archaeological site, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The question of the fate of these children is closely linked to Phoenician and Punic religion, but above all to the way in which religious rites - and beyond that, Phoenician and Punic civilization - were perceived by the Jews in the case of the Phoenicians, or by the Romans during the conflicts that pitted them against the Punics. Indeed, the term "tophet" was originally used to designate a place near Jerusalem, synonymous with hell:[2] this name, taken from biblical sources, leads to a macabre interpretation of the rites supposed to take place there, and corroborates an assumption shared by those who provided sources on the Phoenicians in general and the Punics in particular: religion in Carthage was "infernal". More recently, the collective imagination has been fed by Gustave Flaubert's[3] novel Salammbô[4] (1862), which gave its name to the district where the sanctuary was discovered. The comic strip Le Spectre de Carthage, part of the adventures of Alix written by Jacques Martin, takes up this interpretation.

The major difficulty in determining the cause of the burials lies in the fact that the only written sources reporting the rite of child sacrifice are all foreign to the city of Carthage. As for the archaeological sources - stelae and cippes - they are open to multiple interpretations. As a result, the debate between the various historians who have studied the subject has been lively for a long time, and has yet to be completely settled. The utmost caution is therefore called for, as the ancient historian is faced with written and archaeological sources that are, if not divergent, at least open to interpretation.

Discovery and excavation history

Early stages

The existence of stelae on the site has been known for a considerable period, with the earliest documented references dating back to 1817.[5]These stelae were scattered throughout the Carthage archaeological site due to the dispersal that occurred following its destruction in 146 BC and the subsequent urban development activities that disturbed the soil during the construction of the Roman city. Over time, the Carthage site became a target for significant exploitation, including the quarrying of building materials, including marble. This contributed to the gradual deterioration of the main monuments. Between 1825 and 1827, Jean-Émile Humbert a Dutch soldier and archaeologist, sent cippi and votive bases to the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. The Archaeological Museum of Kraków also has some very fine Punic stelae from the site.[6]

A special place in Carthage's history must also be given to the cargo of the Louvre and the sinking of the Magenta, flagship of the Mediterranean fleet, which sank at Toulon on October 31, 1875, following a fire followed by an explosion.[7] On board were over 2,000 Punic stelae and other artefacts, including the statue of Empress Sabina, wife of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (117-138). The archaeological finds had been loaded at La Goulette, and came from the excavations (authorized by Sadok Bey) of Pricot de Sainte-Marie, an interpreter for the French General Consulate. Following the shipwreck, the divers recovered some of the steles and the statue, while the archaeological pieces were dispersed among various collections, including the Bibliothèque nationale de France. As for the wreck, it was dynamited so as not to impede access to the port. At a depth of twelve meters, what remained of the wreck gradually silted up. Three archaeological campaigns were carried out in 1995-1998 by Max Guérout and the Groupe de recherche en archéologie navale to recover steles and the head of the statue. In April-May 1995, the head of the statue of Sabine was found,[8] followed in April-May 1997 by some 60 fragments of stelae and fragments of the statue. Finally, in 1998, 77 fragments or steles were brought back to the surface.[9]

Jean Herszek Spiro (1847-1914), a pastor and one-time professor at Sadiki College, was one of the pioneers of this field. He returned to Lausanne with 19 stelae, and wrote a book on Les inscriptions et les stèles votives de Carthage ( (1895). We have no indication of the dis)covery of the tophet in either Pricot de Sainte-Marie's or Spiro's excavations. In the case of the former, the discovery of steles reused in walls dating from the Roman period was all that was mentioned. All these remains, originally from the tophet, had been moved in antiquity, and no one was looking for a precise location where they could have been grouped together. Spiro's archaeological collections were mainly epigraphic in nature. A fortuitous discovery was to change our understanding of a whole section of the topography of Punic Carthage.

Discovery of 1921

In 1921, the so-called "priest stele" was unearthed as part of the clandestine archaeological digs that were very common at the time.[10] A limestone stele, over a metre high,[11] depicting an adult wearing a typical kohanim (Punic priest) hat, a Punic tunic and holding a young child in his arms, was offered by an outfitter to enlightened antiquities enthusiasts Paul Gielly and François Icard, civil servants stationed in Tunisia. Faced with a piece that seemed to confirm in every respect the biblical data and certain classical authors, the two enthusiasts were moved and decided to put an end to the clandestinity so that no discovery could escape the notice of archaeologists and historians. They bought the land and excavated it until the autumn of 1922.

The first American excavation, led by Francis Willey Kelsey and Donald Benjamin Harden in 1925, provided a comprehensive understanding of the site's organization. Sadly, Kelsey's death in 1927 brought this excavation session to an end. Father Gabriel-Guillaume Lapeyre, a white father, excavated a neighboring site in 1934-1936 and collected a variety of archaeological and epigraphic material, but without the stratigraphic details needed to understand the context of the discovery.

"Cintas Chapel" and places of worship

From the end of World War II onwards, Pierre Cintas carried out excavations on the site and, in 1947, discovered one of the features that caused such controversy at the time: the feature known as the "Cintas chapel" in honour of its discoverer. Surrounded by masonry in a chamber measuring approximately 1 m², what was interpreted as a high-period foundation deposit was made up of ceramic pieces of various origins dating from the 7th century BC, the earliest evidence of the Phoenician presence on this land. They have been extensively studied and were deposited in crevices in the native soil.[12] The meandering dating of the ceramics in particular, some of which were clearly Aegean, means that the date was lower than that first proposed by Cintas.[13]

Latest American excavations

These latest excavations, linked to the international campaign led by Unesco, took place between 1976 and 1979 under the aegis of the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) and Lawrence Stager.

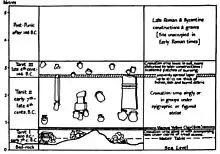

As a result of the excavations, it was proven that the site had been in continuous use for six centuries, with an estimated surface area of 6,000 m², 20,000 urns having been discovered in various strata:

As soon as the sacred area was fully occupied, it was covered with earth, and the depositions began again at the next level[14].

The remains discovered during the initial excavations were subjected to forensic analysis, the results of which caused more confusion than provided answers to the nagging questions posed by specialists.

Site topography and archaeological findings

Site characteristics

"To dig is to destroy": this common adage of archaeologists (the digger destroys the object of his science) is even more valid in the case of the tophet, due to the nature of the site, "a series of superimposed layers of earth, urns and ex-voto" and the superimposition of steles.[15] It should also be pointed out that the site's perimeter was not precisely known, due to the upheaval of the Carthage site since Roman times and the intense urbanization that meant that the tophet was then located in a residential area. Situated at the southern end of the city, close to the commercial port, the site was in a particularly unhealthy, marshy location. During excavations, archaeologists reached a level of brackish water.

The tophet, like that of Motya, was located away from the living and even from the necropolis stricto sensu, and shared four characteristics with the other tophets:

First and foremost, the site is pristine, with no archaeological layers predating the arrival of the Phoenician merchants having been found during the various archaeological excavations. The same applies to the other tophets that have been identified and excavated in the Phoenician-Punic world.

The site is also located in the open air, although the best-known image of the tophet is that of the part located under Roman vaults, which was uncovered during the Kelsey excavations. This image, which admittedly corresponds fairly closely to a place where the much-hated sacrifice would have taken place, is not the space as it appeared at the time, delimited and in the open air.

The third characteristic of a tophet is the fact that the site is usually entirely enclosed: at Carthage, however, the tophet enclosure was only partially recognized at the time of Pierre Cintas's excavations. However, this enclosure seems to have been overrun as early as the 5th century BC. As for the precise surface area of the tophet, it is highly unlikely that it will ever be known, given the urban spread of contemporary Carthage, particularly in the coastal zone.

The final feature of the site is its dual function: votive (stelae dedicated to Ba'al Hammon or Tanit) and funerary (funerary stelae).[16] Evidence of this dual function is to be found in the fact that the term "molk" (offering) is very rarely found in the stelae inscribed with epigraphs, the others being associated with funerary urns with no other indication.

Period organization (Tanit I, II, III)

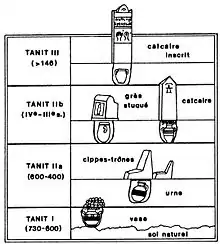

The typology of the finds, and stelae in particular, is the fruit of American excavations, starting with the Kelsey-Harden digs of 1925, and was refined in the 1970s, as summarized by François Decret: "Taking into account the various types of pottery containing the ashes of victims and the installation of sacrificial deposits, we can distinguish three phases in this stratification: the earliest, where the vases were covered under piles of small stones or pebbles; the second [...] which contains urns placed under obelisk-shaped stones, baetylus or under cippes of various types; and the most recent, characterized by flat stelae with triangular tops, sometimes flanked by acroterion".[17]

The depositions all have a stereotypical character: a buried urn surrounded by stones containing burnt bones, accompanied by funerary offerings such as terracotta masks and small glass paste masks found during archaeological excavations, and surmounted by monuments, which may have been steles or cippes.

Excavations have enabled us to characterize the various periods in which the tophet was used, moving from an Egyptian influence to a Hellenistic style:[15] the first, known as Tanit I (750 B.C.-600 B.C.) features sandstone cippes and baetylus, with the urns deposited in crevices in the native soil and a sandstone cippe-trone. The Tanit II period (5th century BC - 8th century BC) presents a sub-section: the cippe-trone is still present at Tanit II-a, but at Tanit II-b, it is replaced by limestone steles. The last period of use of the site, Tanit III (2nd century BC -146 BC), features fine limestone stelae (1st century BC) with acroteria, sometimes richly decorated with carvings of various motifs.

Types of motifs found on stelae

These signs are particularly common on late stelae, as the shapes of early stelae are indicative of influences, particularly Egyptian.

There are many religious symbols, including the sign of Tanit, long considered to be specific to the Phoenicians of the western Mediterranean basin, but examples of which have been discovered in excavations in present-day Lebanon. The sign of the bottle is also very present,[15] having been identified with the mother goddess who has always been present in the Mediterranean basin. The astral signs, moon and sun, are also represented and sometimes intertwined to form a rosette; these signs are symbols of eternity.

On later stelae, figurative ornamentation emerges: animals (elephants), vegetal elements (palm trees), humans, such as an open hand, portraits revealing Hellenic influence and, of course, representations of men in their entirety (scene of the priest with the child) and marine elements (boat). This blending of Semitic features and external contributions is most evident when Carthage comes into contact with the Greek world, particularly Sicily.

Punic epigraphy

The stelae were sometimes engraved with inscriptions of the same type, but which revealed the tophet as "a sanctuary of popular expression and fervent piety".[18]

The dedicators either made a wish or thanked for its fulfillment: "To the great lady Tanit Péné Ba'al and to the lord Baal Hammon, what [such-and-such], son of [such-and-such], has offered, may they [Ba'al] or she [Tanit] hear [his] voice and bless [him]". The inscriptions were stereotyped in a "desperately dry and repetitive form".[19]

Late stele with elephant.

Late stele with elephant. Stele in the form of a Tanit sign with bottle sign.

Stele in the form of a Tanit sign with bottle sign. Stele with sign of Tanit, intersecting moon and rosette, and pomegranate.

Stele with sign of Tanit, intersecting moon and rosette, and pomegranate. Stele with Tanit sign and astral symbols.

Stele with Tanit sign and astral symbols. Stele with palm trees and wings of Egyptian inspiration.

Stele with palm trees and wings of Egyptian inspiration. Stele with obelisk and inscription.

Stele with obelisk and inscription. Late stele with limestone acroterion and ship.

Late stele with limestone acroterion and ship. Small group of Tanit II stelae.

Small group of Tanit II stelae.

Roman occupation of the site

In Roman times, the site was reused: the foundations of a temple dedicated to Saturn were uncovered during excavations, and numerous foundations for later buildings pierced the archaeological layers. Also visible on the site are Roman foundation piers, at the site of the tophet excavated by Pierre Cintas, craftsmen's workshops (potters) and hangars, as well as houses that had yielded mosaics, including a mosaic of the Seasons now in the Bardo Museum.[20]

The current site is an important part of the tour of ancient Carthage, although the layout is a motley collection of stelae from various periods, especially the earliest. Almost all the stelae on display are of El Haouaria sandstone, although there are a few later limestone stelae in the vaulted section.

Questions about site interpretation

Charged sources

.jpg.webp)

The ancient sources that mention the religious rites of the Punics are Greek and Latin. Diodorus Siculus refers to them at length in connection with the attack on Carthage by Agathocles, tyrant of Syracuse:[21] "They [the Carthaginians] considered that Cronus was also hostile to them, because they, who had previously sacrificed the best of their sons to this god, had begun secretly buying children whom they then fed and sent to the sacrifice. Upon investigation, it was discovered that some of the sacrificed [children] had been substituted. Considering these things, and seeing the enemy [Agathocles' army] encamped before the walls, they felt a religious dread at the thought of having ruined the traditional honors due to the gods. Burning with the desire to right their wrongs, they chose two hundred of the most respected children and sacrificed them in the name of the state. Others, against whom there were murmurs, voluntarily surrendered themselves; they numbered no less than three hundred. Among them [in Carthage] was a bronze statue of Cronus, with hands outstretched, palm up, and bent towards the ground, so that the child placed in it would roll and fall into a pit full of fire".[22]

Dionysius of Halicarnassus refers to the supposed human sacrifices in his Antiquités romaines (I, 38, 2): "It is said that the ancients sacrificed to Cronus in the way that was done in Carthage for as long as the city lasted".[23] Porphyry of Tyre, in De l'abstinence (II, 56, 1) states that "the Phoenicians, on the occasion of great calamities such as wars, epidemics or droughts, sacrificed a victim taken from among the beings they cherished most, whom they designated by vote as the victim offered to Cronus".

In De la superstition (XIII), Plutarch accuses parents of failing to show piety towards their children: "The Carthaginians offered their children with full awareness and knowledge, and those who had none bought those of the poor like lambs or young birds, while the mother stood by without tears or moaning. If she moaned or cried, she was to lose the sale price, and the child was still sacrificed; however, the whole space in front of the statue was filled with the sound of flutes and drums, so that the cries could not be heard".

Later, Tertullian, in the Apologeticus, considered that "children were publicly immolated to Saturn, in Africa, until the proconsulship of Tiberius, who had the very priests of this god exposed, tied alive to the very trees of his temple, which covered these crimes with their shadow, as to so many votive crosses: I take as witness my father who, as a soldier, carried out this order of the proconsul. But even today, this criminal sacrifice continues in secret".[24]

Silence from other major sources

Faced with these damning texts, it's worth pointing out the silence of other historians, particularly when it comes to major sources for ancient history such as Herodotus, Thucydides, Polybius or Livy Titus, Lancel points out that "[this] silence [...] stands out sharply in the concert of accusations of impiety and perfidy that are, among classical authors, the usual lot of the Carthaginians".[25] According to this specialist, such an absence makes sense, as these ancient authors would point out any attitude they found shocking in relation to the ordinary practices of their Greek or Latin cultures.

Historiography of the debate

In his novel Salammbô, published in 1862, Gustave Flaubert refers to the sinister deity Moloch, who made "the burning of newborn babies a common practice in Carthage".[26] Already at this time, voices were raised against this interpretation of sources hostile to the Carthaginians, including Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve.

The site of Tanit's sanctuary is named Salammbô in the topography of the modern city of Carthage, in line with Flaubert, and the sanctuary itself named "tophet", a Hebrew term (tpt) highly connoted in favor of the interpretation of child sacrifice.[27] James Germain Février supports the child-sacrifice interpretation: "It's night! The scene seems to be lit only by a brazier lit in the sacred pit, the tophet: we see its reflections rather than its glow [...] The father and mother are present. They hand the baby over to a priest who walks along the pit, slits the child's throat in a mysterious manner [...] then places the little victim on the outstretched hands of the divine statue, from where it rolls into the blaze".[28] As early as 1922, Charles Saumagne warned his contemporaries against such an interpretation, considering that "it is important, before advancing the matter, even as a hypothesis, to know the excavation perfectly in all its details".[29]

Current debates

This is not just a reminder that human sacrifice, "an act(s) of profound piety",[20] was widespread, particularly in times of trouble and difficulty. Mythology echoed this practice in the myth of Iphigenia, and here it's sufficient to recall that in Rome itself, in 216 BC, a Gaulish couple and a Greek couple were sacrificed on the Forum Boarium, a sacrifice recounted by Titus Livy in his History of Rome from its foundation:[30]

However, on the advice of the Books of Destiny, several extraordinary sacrifices were made: among others, a Gallic man and a Gallic woman, a Greek man and a Greek woman, were buried alive in the ox market, in a stone-enclosed area that had already been sprinkled with the blood of human victims, an un-Roman religious ceremony.[31].

When the tophet was first discovered, Charles Saumagne was outraged by the conjectural claims and interpretations. The debate has always been lively, with successive research still unable to settle it definitively. Ancient historians were still clashing recently, following the conclusions of the American ASOR team. According to Lawrence Stager, "content analysis and archaeological context, as well as reconsideration of written sources [...] demonstrate beyond doubt that child sacrifice was practiced in Carthage from at least 750 BC until the city's destruction".[32] The same author points out that "in Carthage, child sacrifice had not only a religious dimension, but also social and economic aspects [...] Infanticide seemed less risky for the mother's health than aborting a fetus; moreover, this practice enabled parents to regulate births and make a selection by sex. Among Carthage's economic elite, the religious institution of child sacrifice may have been used by wealthy families to consolidate and maintain their fortunes by enabling them to moderate the number of male heirs between whom the inheritance should have been divided, as well as the number of daughters to be endowed at the time of their marriage".[33] Ennabli and Slim subscribe to this thesis of the "sacrifice of their offspring to the protective deities of the city",[15] even citing elements of Flaubert's work, the "terrible reality of the rite" being established according to their 1993 book.[34]

Sabatino Moscati asserts that "the tophet, a sacred area dedicated to the two supreme deities Tanit and Ba'al Hammon, was the place where stillborn children or those who died shortly after birth were burned and then buried in urns. The tombs of very young children, not found in necropolises, were actually located in the tophet. The sanctuary thus housed the remains of those who, having died too soon, were excluded from adult society and its necropolises. There, they were dedicated or offered to the divinity by being ritually cremated".[35] The tophet is thus seen as a "hybrid of sanctuary and necropolis",[1] with young children buried in the same place, where "occasional human sacrifices were made, as was the case with many peoples of the period".[1] In fact, according to Michel Gras, sacrifices could be carried out exceptionally in particularly serious circumstances.[36]

According to François Decret,[37] but also Michel Gras and his colleagues, a substitute sacrifice known as "molchomor" (sacrifice of the lamb) was gradually introduced, with the sacrifice being performed "breath for breath, blood for blood, life for life",[38] particularly in the Neo-Punic period following the Third Punic War.[20] The difficulty of this interpretation lies in the use of first-century Roman inscriptions, and in the fact that analysis of the urns' contents shows a reduction in the proportion of substitutions over time.

A debate not yet settled by medicine

As soon as the site was discovered, archaeologists were keen to set up proper forensic analyses,[39] even if the unavowed aim was to find confirmation of the assertions made by the most prolix ancient authors about the Carthaginians. Analyses were carried out between 1947 and 1952 at the Lille Institute of Forensic Medicine.[40]

Scientists took samples and studied the contents of the urns: this led to the identification of bones from very young children (maximum three years old), with the exception of a single case of a child aged around twelve.[41] The urns also yielded the remains of small animals, including caprids and a few birds. An evolution over time can be observed: whereas the urns analyzed and dated from the 6th century B.C. included around a third of substitutions, by the 4th century B.C., the proportion of small animal remains was one in ten.

The interpretation of these analyses is problematic: the results of analyses carried out by the Lille Institute of Medicine have given cause for concern, with doctors refusing to consider tophets as "necropolises reserved for the corpses of children or fetuses, or newborns, corpses incinerated before burial".[42] Medicine is currently unable to indicate the reasons for the deaths, and it is impossible to say "whether the cremated children were placed alive on the pyre or had already died a natural death"; nevertheless, it should be remembered that the necropolises of Punic Carthage did not yield any tombs of newborn babies, and Azedine Beschaouch tends to make the tophet the "burial place for fetuses and stillborn babies" who would have been cremated.[40]

For Salammbô's tophet, until a new discovery is made, the comparison of written and archaeological sources remains open to debate, as the meeting of diverse and convergent sources so eagerly awaited by historians and archaeologists has not yet taken place.

See also

References

- Benichou-Safar, Hélène, « Les rituels funéraires des Puniques », La Méditerranée des Phéniciens : de Tyr à Carthage (in French), Paris, Somogy, 2007, p. 255.

- To learn more about this subject, please consult the articles Tophet and Gehenna.

- The author describes the rite described in his novel as "grilling mustards", quote from Collectif 2007, p. 62

- This applies in particular to the chapter entitled Moloch.

- Humbert 1821, p. 2.

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 44.

- "Magenta". archeonavale.org (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2021..

- Notice n°21917, base Atlas, Louvre.

- On this subject, see "Archéologie sous-marine". culture.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2021..

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 76.

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 77.

- Charles-Picard & Picard 1958, p. 37-45.

- Pierre Cintas changed his interpretation of the discovery between his 1948 article in the Revue tunisienne entitled "Un sanctuaire précarthaginois sur la grève de Salammbô", in which he initially dated the deposit to the end of the 2nd millennium BC, and the first volume of his Manuel d'archéologie punique (p. 315-324) published in 1970, in which he placed it in the first half of the 7th century.

- Lipinski 1992, p. 463.

- Ennabli & Slim 1993, p. 36.

- Sznycer Maurice , «La religion punique à Carthage», Carthage: l'histoire, sa trace et son écho (in French), Paris, Association française d'action artistique, 1995, pp. –100-106.

- Decret 1977, pp. 145–146.

- Bénichou-Safar, Hélène, « Les rituels funéraires des Puniques », La Méditerranée des Phéniciens : de Tyr à Carthage (in French), Paris, Somogy, 2007, p. 254.

- Lancel 1992, p. 340.

- Ennabli & Slim 1993, p. 38.

- Slim & Fauqué 2001, p. 64.

- See the critical reading of this text in Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1994, pp. 178–179.

- Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1994, p. 176.

- Tertullien, Apologétique, IX, 2-3.

- Lancel 1992, p. 348.

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 74.

- Beschaouch 2001, pp. 74–76.

- Quoted by Azedine Beschaouch in Beschaouch 2001, p. 77.

- Quoted by Azedine Beschaouch in Beschaouch 2001, p. 78.

- Tite-Live, Histoire de Rome depuis sa fondation, Livre XXII, 57.

- Latin: Interim ex fatalibus libris sacrificia aliquot extraordinaria facta, inter quae Gallus et Galla, Graecus et Graeca in foro bouario sub terram uiui demissi sunt in locum saxo consaeptum, iam ante hostiis humanis, minime Romano sacro, imbutum.

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 79-80.

- Stager 1992, p. 75.

- Ennabli & Slim 1993, p. 37.

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 80.

- Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1994, p. 180.

- Decret 1977, pp. 138–147.

- Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1994, p. 178.

- Both the Icard excavations of 1922-1924 and the Cintas excavations, and more recently that of Lawrence Stager.

- Beschaouch 2001, p. 78.

- Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1994, p. 186.

- P. Rohn, author of a thesis in 1950 on the determination of the age of children cremated in Carthage and Sousse quoted by Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1994, p. 186.

References

General works on the Phoenicians or on Rome in Africa

- Fontana, Elisabeth; Le Meaux, Hélène (2007). La Méditerranée des Phéniciens: de Tyr à Carthage (in French). Paris: Institut du monde arabe/Somogy. ISBN 978-2757201305..

- Baurain, Claude; Bonnet, Corinne (1992). Les Phéniciens: marins des trois continents (in French). Paris: Armand Colin. ISBN 2200212232..

- Gras, Michel; Rouillard, Pierre; Teixidor, Javier (1994). L'univers phénicien (in French). Paris: Arthaud. ISBN 2700307321.

- Hugoniot, Christophe (2000). Rome en Afrique: de la chute de Carthage aux débuts de la conquête arabe (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 2080830031..

- Lipinski, Edward (1992). Dictionnaire de la civilisation phénicienne et punique (in French). Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 2503500331.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1997). Les Phéniciens (in French). Paris: Stock. ISBN 2234048192..

- Collectif (5 November 2007). "La Méditerranée des Phéniciens". Connaissance des arts (in French) (344). ISSN 0293-9274.

General works on Carthage

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2007). Carthage (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2130539629..

- Beschaouch, Azedine (2001). La légende de Carthage. Archéologie (in French). Paris: Éditions Gallimard. ISBN 2070532127.

- Charles-Picard, Gilbert; Picard, Colette (1958). La vie quotidienne à Carthage au temps d'Hannibal (in French). Paris: Hachette.

- Decret, François (1977). Carthage ou l'empire de la mer (in French). Paris: Seuil-Points histoire. ISBN 2020047128.

- Dridi, Hédi (2006). Carthage et le monde punique (in French). Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 2251410333..

- Ennabli, Abdelmajid; Slim, Hédi (1993). Carthage: le site archéologique (in French). Tunis: Cérès. ISBN 997370083X.

- Hassine Fantar, M'hamed (1995). "Architecture punique en Tunisie". Dossiers d'archéologie (in French) (200): 6–17. ISSN 1141-7137.

- Hassine Fantar, M'hamed (1998). Carthage: approche d'une civilisation (in French). Tunis: Alif. ISBN 9973220196..

- Hassine Fantar, M'hamed (2007). Carthage: la cité punique (in French). Tunis: Cérès. ISBN 9973220196..

- Gifford, John A.; Rapp Jr., George; Vitali, Vanda (1992). "Palaeogeography of Carthage (Tunisia): coastal change during the first millennium BC". Journal of Archaeological Science. 19 (5): 575–596. ISSN 0305-4403.

- Lancel, Serge (1992). Carthage (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2213028389.

- Mendleson, Carole (1995). "Catalogue of punic stelae in the British Museum". In Institut national du patrimoine (ed.). Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress of Phoenician and Punic Studies (Tunis, November 11-16, 1991). Vol. 2. Tunisia. pp. 258–263.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Picard, Colette (1990). "Les sacrifices Molk chez les puniques : certitudes et hypothèses". Semitica (in French). 39: 77–88.

- Slim, Hédi; Fauqué, Nicolas (2001). La Tunisie antique: de Hannibal à saint Augustin (in French). Paris: Mengès. ISBN 285620421X.

- Slim, Hédi; Mahjoubi, Ammar; Belkhodja, Khaled; Ennabli, Abdelmajid (2003). Histoire générale de la Tunisie (in French). Vol. I. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 2706816953..

- Stager, Lawrence (1978). "Excavations at Carthage: The punic project". In Institut oriental de Chicago (ed.). Annual Report. Chicago. pp. 27–36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sznycer, Maurice; Nicolet, Claude (2001). "Carthage et la civilisation punique". In Presses universitaires de France (ed.). Rome et la conquête du monde méditerranéen (in French). Vol. 2. Paris. pp. 545–593. ISBN 978-2130519645.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tlatli, Salah-Eddine (1978). La Carthage punique: étude urbaine, la ville, ses fonctions, son rayonnement (in French). Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve.

- Collectif (1995). Carthage: l'histoire, sa trace et son écho (in French). Paris: Association française d'action artistique. ISBN 9973220269..

- Collectif (1992). Pour sauver Carthage: exploration et conservation de la cité punique, romaine et byzantine (in French). Paris/Tunis: Unesco/INAA. ISBN 9232027828.

Specific work on the Carthage tophet

- Bénichou-Safar, Hélène (1981). "À propos des ossements humains du tophet de Carthage". Rivista di Studi Fenici Roma (in French). 9 (1): 5–9. ISSN 0390-3877.

- Bénichou-Safar, Hélène (2004). Le tophet de Salammbô à Carthage: essai de reconstitution (in French). Rome: École française de Rome. ISBN 2728306974..

- Bénichou-Safar, Hélène (1988). "Sur l'incinération des enfants aux tophets de Carthage et de Sousse". Revue de l'histoire des religions (in French). 205 (1): 57–67. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Benichou-Safar, Hélène (1995). "Les fouilles du tophet de Salammbô à Carthage (première partie)". Antiquités africaines. 31 (1): 81–199. doi:10.3406/antaf.1995.1236.

- Eremin, Katherine; Degryse, Patrick; Erb-Satullo, Nathaniel; et al. (yes) (2010). "Amulets and Infant Burials: Glass beads from the Carthage Tophet". In British Museum (ed.). SEM and microanalysis in the study of historical technology, materials and conservation conference, 9-10 September 2010, London, UK. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gutron, Clémentine (2008). "La mémoire de Carthage en chantier : les fouilles du tophet Salammbô et la question des sacrifices d'enfants". L'Année du Maghreb (in French) (4): 45–65. ISSN 1952-8108. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Humbert, Jean Emile (1821). Notice sur quatre cippes sépulcraux et deux fragments, découverts, en 1817, sur le sol de l'ancienne Carthage [Note on four sepulchral skullcaps and two fragments discovered in 1817 on the soil of ancient Carthage] (in French). The Hague: M. de Lyon. OCLC 457304341.

- Hurst, Henry; Ben Abdallah, Zeïneb; Gordon Fulford, Michael; Henson, Spencer (1999). "The sanctuary of Tanit at Carthage in the Roman period". Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Lancel, Serge (1995). "Questions sur le tophet de Carthage". In Faton (ed.). La Tunisie : carrefour du monde antique. Dijon. pp. 40–47.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schwartz, Jeffrey H. (1997). "Infants, burned bones, and sacrifice at Ancient Carthage". In University of Arizona Press (ed.). What the Bones Tell Us. Tucson. pp. 28–57. ISBN 978-0816518555.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schwartz, Jeffrey H. (1989). "The Tophet and sacrifice at Phoenician Carthage: an osteologist's perspective". Terra. 28 (2): 17–25.

- Schwartz, Jeffrey H.; Houghton, Frank D.; Bondioli, Luca; Macchiarelli, Roberto (2013). "Bones, teeth, and estimating age of perinates: Carthaginian infant sacrifice revisited". Antiquity. 86 (333): 738–745. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Schwartz, Jeffrey H.; Houghton, Frank D.; Bondioli, Luca; Macchiarelli, Roberto (2010). "Skeletal remains from punic Carthage do not support systematic sacrifice of infants". PLOS One. 5 (2). ISSN 1932-6203.

- Smith, Patricia; Avishai, Gal; Greene, Joseph A.; Stager, Lawrence (2011). "Aging cremated infants: the problem of sacrifice at the Tophet of Carthage". Antiquity. 85 (329): 859–874. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Smith, Patricia; Avishai, Gal; Greene, Joseph A.; Stager, Lawrence (2013). "Cemetery or sacrifice? Infant burials at the Carthage Tophet". Antiquity. 87 (338): 1191–1207. ISSN 0003-598X.

- Stager, Lawrence (1992). "Le tophet et le port commercial". In Unesco/INAA (ed.). Pour sauver Carthage : exploration et conservation de la cité punique, romaine et byzantine (in French). Paris/Tunisia. pp. 73–78. ISBN 9232027828.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Stager, Lawrence (1984). "Phoenician Carthage: The commercial harbour and the tophet". Qadmoniot. 17: 39–49. ISSN 0033-4839.

- Stager, Lawrence; Niemeyer, Hans Georg (1982). "Carthage: A view from the Tophet". In von Zabern, Philipp (ed.). Phönizier im Westen: die Beiträge des Internationalen Symposiums über 'Die phönizische Expansion im westlichen Mittelmeerraum' in Köln vom 24. bis 27. April 1979. Mayence. pp. 155–166.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)